Well, proof is a strong word. But I’d think that the aging of the classical music audience — over just about a 50-year period — is a very strong sign that our culture has shifted. And shifted away from classical music.

But first a step backward. I’m writing more posts in my current series than I expected to. So to get reoriented: My main thesis is that building a new, young audience for classical music ought to be our most urgent priority. Why? Because we’re losing the audience we have, and there will never be another audience — or at least not one nearly as big as the current one — that will embrace classical music as we present it now.

To find that new young audience, we’ll have to make big changes. To quote what I wrote earlier, we have to: (1) change the way we present classical music (2) change the repertoire we play, and (3) play our music more vividly. (Earlier, I said “play better,” but that’s not accurate, and gave the wrong impression that I think we play badly.)

If you follow the link, you’ll find quite a lot on the changes we have to make in our presentation. And, no, they don’t involve concert enhancements, like (for instance) changing the lighting in the hall when the mood of the music changes. Instead, we have to change the way a concert feels, so that people who come feel welcomed, involved, and fully informed about what’s happening onstage.

So, having said all that, now I’m going through the reasons for changing the music we play. They’re tied up in the changes we’ve seen in the culture around us. Scroll back to see a few ways I’ve addressed this. After this post, I’ll go on to the music itself — what, exactly, the repertoire changes might be.

But about the age of the audience. For many years, most of us thought that the classical audience has always been old. But that’s not the case. Surveys done in past generations — going back to the ’60s and earlier — show an audience much younger than the one we have now, an audience with a median age in its thirties. I’ve collected this data, plus anecdotal evidence, here. (I seem to be the first in our time to discover this data and make it available, for which I’m happy to take credit.)

So here’s the true picture. Up through the 1960s, we had an audience no older, roughly speaking, than the population at large. In the ’70s, it started to age, and it’s been aging ever since. (Though possibly we’ve chipped away just a bit at that, with energetic programs — special concerts, discount tickets, and the like — to attract younger people.)

In the 1980s, according to data from the National Endowment for the Arts, the percentage of the classical music audience under 30 fell in half. And since then, the attendance of older age groups has also declined, until by 2008 (again according to NEA data) only people 65 and older go to classical performances as often as their counterparts did in the past.

Why would this have happened? Was it (as I know many of us believe) because classical music stopped being taught in our schools? Not likely. The younger people who — unlike their counterparts in earlier decades — so notably didn’t go to classical concerts in the ’80s, grew up at a time when classical music in fact was still taught. But the teaching didn’t make them classical music fans. (If you read Dave Marsh’s book, The Second Beatles Album, you’ll find a leading rock critic slamming into the music education classes he took as a high school kid in the ’60s, finding them repressive and out of touch with the world around him.)

So I think the audience aged because the culture changed. Here are some things that I’m sure we all know, but I’ll say them, just to emphasize how great the change was. Even before the ’60s, something radical happened: a new generation of white teenagers started listening in the ’50s to what essentially was black popular music, otherwise known as rock & roll. We’d never had such an irruption of black culture into the white mainstream. In the ’60s, rock (after years in which it sounded more white) took a decisive turn back to its black roots. Along with that came the civil rights movement, bringing all kinds of black ideas, culture, and politics into mainstream culture.

None of this touched classical music in any substantial way. And this is just one of many cultural changes. I recommended, in my last post, a book by Mark Harris called Pictures at a Revolution, which shows how movies changed in the ’60s — how, in fact, Hollywood split into old and young factions, and the young factions (influenced by avant-garde films from France) won, changing the movies for ever. Popular culture was becoming art, something we also (of course) saw happen in rock.

So people who grew up in the ’60s — and, even more, the two decades after, when the changes dug themselves in deeper — didn’t relate to classical music as earlier generations had. It didn’t reflect their world.

And they acted on this, by not going to classical concerts. The people 30 and under who stopped going to classical performances in the ’80s were born in the ’50s and ’60s. Which means that — most crucially — they grew up either in the ’60s or in the ’70s, making them the first generation to come of age after things started to change. They grew up in the emerging new culture.

Now move the clock forward. With each passing decade, the culture changes even more. and younger people move further from classical music (further from its sound, its sensibility, and from the kind of life depicted in the older masterworks). They listen to it even less than their counterparts in previous decades did, and go to fewer classical concerts.

And people a little older also go less than their counterparts in earlier decades. In 1990, people aged 40 to 50 were born between 1940 and 1950, which means they grew up just as the culture was starting to change, at a time when the classical audience still was young. They took to classical music easily, and kept up their interest as they grew older. Which in 1990 made them a strong segment of the classical audience.

But the clock keeps moving. Soon it’s 2000. People now in their 20s grew up in an age when the new culture had pretty much taken over. Classical music already had already begun to. They’re not going to be in the classical audience, now or later (and in fact, as I’ve said, haven’t been since the ’80s). People in their 30s, too, grew up after classical music began to lose its central position in our culture, so they go less often than their earlier counterparts did.

But people 40 to 50? And above? They’re still prime classical music lovers, and now form the core of the classical music audience. They’re the same people who were 30 to 40 (and above) in 1990, and they’re still going to orchestral concerts, opera, chamber music, solo recitals.

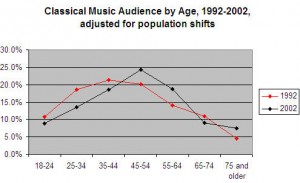

Here’s a chart I made from NEA data, showing this happening:

In 1992, the largest age group in the classical music audience was 35 to 44. In 2002, the largest age group is people 45 to 54 — the same people who were the largest age group in 1992, now 10 years older. (I’ve adjusted the data for shifts in the overall age of the population. So the numbers show not the actual percentage of each age group in 2002, but what the percentage would have been if the number of people in that age group — in the entire population — had stayed the same.)

And thus the audience ages. By 2012, the dominant group should now be 55 to 64.

The key to all this — the most important thing to remember — is that what shapes your relation to classical music isn’t how old you are. It’s when you were born. If you grew up when younger people naturally turned to classical music, you may well develop an interest, and keep that interest as you grow older. But if you grew up after the culture started to change, you may not develop that interest.

And so, as the decades pass, the audience gets older and older. And of course that means it shrinks. Some younger people come into it, of course. But there aren’t enough of them. There aren’t enough to keep the younger segments of the audience as large as they’d been in the past.

We can’t roll back the culture change, so the only way to make the audience younger — which we have to do, if we want it still to exist — is to bring the cultural changes into classical music.

Which, as we’ll see, will make things smarter, more artistic — certainly more creative — and a lot more fun. Details to come.

Hi Greg! I would add that women are havng children later. This is important because it affects when a couple begins to have the time and inclination to go out again! I honestly think this is a bigger factor than it would seem.

Hi, Alecia,

Good thought. There surely is data that would tell us more. One thing occurs to me — if this is a factor at all, it ought to affect every kind of going out, not just classical performances. And women might be going to concerts when they were younger, before they had children.

Of course, your organization (River Oaks Chamber Orchestra, for those who don’t know) offers childcare during concerts, so you’re addressing the problem head-on.

A piece of data from the past — up to at least the 1950s, women identified as “housewives” made up a big part of the classical music audience. In a 1955 survey in Minnesota, they were one of the top four job categories, the others being businessmen (sic), professionals, and students. Since half the audience was under 35, I’d think many of the housewives (sic again) were, too.

It would be interesting to break out the classifications by category within the pooled data, orchestral, opera, solo concerts, vocal concerts. As I live in NYC, which perhaps is the largest audience for classical music in the Country, I still find most of the classical events I go to heavily populated by the let’s say 60 and over crowd. Obviously your entire premise is extremely valid, but for instance Peter Gelb has barely made a dent in the average age of the audience who is paying for full priced tickets at the MET with all of his gimmicky productions. He lures them in for the plentiful $25 sponsored Rush seats. His HD movie theatre runs have become an activity for old age homes to do on a Saturday afternoon for those mobile enough to get transported to the theatres. I once went and counted the oxygen bottles……not a small number.

The NY Phil I find much the same, but Carnegie Hall on ther other hand appears to be winning a younger audience.

The NEA has separate categories for opera and classical music (very confusing). The opera numbers are about the same as the classical music ones.

You’re so right about the Met’s movie screenings. A very elderly audience. The biggest outpouring of younger people at NYC concerts, in my experience, is for new music. And, anecdotally, chamber music around the country has the oldest audience.

“And, anecdotally, chamber music around the country has the oldest audience.” Interesting, but a lot of new music is being written for smaller forces (ie. chamber music). I’ve not written an orchestral work in years, and I know a lot of composers who aren’t all that interested in writing for the bloated dinosaurs.

Of course. I’m talking, as I would have thought would be clear, about standard-issue chamber music performances, especially those on established chamber music series. That other kinds of performances might also be called chamber music doesn’t escape me, but has nothing to do with the point I thought I was making.

sorry.

I guess that I was trying to make the point that small ensembles might be key to broadening the interest in “Classical Music”, I guess I don’t go to “standard issue” chamber concerts unless they are mostly 20th-21st century music. In these cases I noticed that the age of the audience tended to be younger. I’ve heard about the CSO forming chamber ensembles, and I believe this might be a viable way that orchestras could reach out to new audiences. The smaller the ensemble the easier it is to play in alternate venues.

Personally, I’m tired of “Romantic” overreach. “Big Statement” art. Grand opera and the modern symphony are quite good at doing that sort of thing. And let’s face it, these sort of ensembles and their

repertoire are thought to be the Apex of western art music. They won’t cede their musical/cultural prominence easily. If the Wall Street debacle has taught us anything, it’s that bigger is not always better, and I think that this holds true for arts institutions.

There is an immediacy/intimacy one finds in chamber music that is lacking in concert halls ans opera houses. You see the performers sweat, it’s music making with a “human face”, warts and all. It is music that connects more with people than with an “audience”. Jazz musicians know this in their bones. I’ve experienced this, and it is different than playing in a large group on stage before a large audience. Of course, there are alway folks who love “big art”, be it arena rock or grand opera, maybe art music needs to connect on a more intimate level.

I agree. Probably I’m by temperament more sympathetic to big statements than you might be, though the main classical world has ODd on them, at least to my taste. What you say resonates very strongly with me. Thanks!

I agree with much of what you have written, but there are other factors that affect the audience. Partly, classical music concerts are over-hyped. Read any classical music brochure and note how many adjectives appear such as “extraordinary, transcendent, thrilling, masterpiece, towering, mystical, irresistible, unforgettable.” The reality is somewhat different and young audiences come away from a concert wondering “Did I miss something?” And they don’t ever come back.

I agree, Carlo. I’ve written about that a lot. One recent press release I got, for Thomas Hampson’s summer schedule, is so full of repetitive, uninformative praise that it’s just about unreadable.

You have me waiting on pins and needles, Greg! (Seriously)

Thanks, Brian! I’m taking this week off from blogging. Having a restful time in the country, and getting some other things done. Plus lots of family time. Next week I’ll resume.

Greg, you always make great points. Thanks for what you are doing for the industry. We should consider not just the age but the population demographics. A long term approach requires looking not just at age, but economic background, ethnic orientation, and number of people per age group over time. The 65 and older group has often been the preferred market as they have the time and discretionary income to be ticket buyers and contributors. We also have to look at the value equation. It is rarely mentioned, but might very well prove worth a look. Keep up your fine word.

They’re certainly a preferred market for the development department! Big classical music institutions are wary about getting a younger audience, because it wouldn’t donate as much.

Go back to 1966, and things look different. Classical music institutions didn’t have development department. The audience had a median age of 38. And the study of the audience from which I get that number made a great point of saying that the youth of the audience (for all the performing arts) was one of its most notable characteristics. And also that people _stopped going_ to performing arts events as they got older! You read that, and you feel you’re looking at another planet.

I (b,1949) developed a particular interest in classical music because two key people in my life encouraged me, despite neither of them being particularly committed. They were my Father and my Aunt. I remember my father playing the Eroica on 78’s as a way of interacting with us when he was working away from home. Both my older brother and I heard the music. Yet he queued up for Beatles singles while I listened to Schoenberg on my crystal set. I felt pressurised by the consumer culture of the Sixties, but along with another school friend, resisted it. My Aunt defended me against the pressure in my own family. Later my Father objected to Webern being played in the house and my mother audited my interest in Mahler. Neither of them objected to my brother’s musical interests simply because they could not relate to them and twelve-tone music was more of an assault on their values than the sugary froth of the Beatles. I was typically on the cusp of a change that took over the Western world. As much as I agree with Greg Sandow’s conclusions I think he has omitted one crucial point: the inability of the Classical tradition to reach its inherited audience with its innovations. Junk filled the void.

Duncan, thanks for the reminiscences. I’m picturing you listening to Schoenberg on your crystal radio! Takes me way, way back. Who was broadcasting Schoenberg in those days?

I wouldn’t call popular culture junk. That discussion is an important watershed for classical music. If we think popular culture is junk, we misread it seriously, and run the risk of looking a little silly (sorry to say that) to outsiders, who know what the truth really is.

The rock that exploded during the ’60s was hardly commercial culture. It was a counterculture — an alternative to the prevailing commercial culture. Some of the most important innovators, like Bob Dylan, had very few songs on the pop charts.

Terrific overview of the culture shifts through the latter 20th century. Looking forward to your further thoughts as to how to assimilate cultural changes into classical music. I’ve heard the term ‘branding’ more and more in recent years, of musicians themselves. A small few take this idea in changing their attire in concert from the traditional look to something more contemporary, but I believe, as you say, the repertoire and how it is presented (or may I add, blended with the tried and true) is only one example. Very eager to follow your thread in all of this, since you have devoted so much time and heart and soul to this ongoing situation.

Thanks for the warm words, Jeffrey. You know I’ve been teaching workshops on branding for classical musicians. They take place online, so anyone can take part. (And I seem to be international — I’ve had people from Canada, South Africa, and, coming up, Australia.)

One thing I stress is that branding isn’t done in any one way. Sure, you can dress more informally, but if that’s all your brand is, it’s a pretty shallow brand. Branding comes from the totality of what you do, and how you present yourself. Some part of it — Jean-Yves Thibaudet’s red socks, for instance — may become a symbol for everything else, but it’s only a symbol. The totality has to be there for the branding to succeed.

Anyone interested in the workshops can go here for more info: http://www.gregsandow.com/branding-workshops.

Fantastic! I will peruse the site. You are correct that branding is a totality of the equation. In some ways, I am glad to be slightly over 50 years of age. One expects more about the music and less about the person, I believe, once an artist reaches ‘age’. If I were in my 20s, my career path would be carved out much differently–attire, etc. I admit, it would have been much easier if I were in my 20s now, with the internet, You Tube and acceptance of repertoire that was considered taboo for a ‘serious’ artist to do 25+ years ago. Branding, to me, is one’s ‘shtick’, well, for lack of a better word. My shtick is repertoire, and advancing repertoire, and playing various styles without compromise. It took me 20 years to ‘brand’ myself that way, but it often takes time for artists of any age to become widely known and accepted for their ‘brand’. I agree with many of the points shared above–especially the ages of many new parents. When I was a youngster in the mid 1960s into the 1970s, most of my friend’s parents had their children before they were 30. My mother had all four children before she was 29! If you do a scenario and/or exploration across the USA of age brackets of families with children under the age of 12, it might vary widely opposed to the 1950s and 1960s. Oh–if you see the new movie, “Moonrise Kingdom”, one interesting thing about the film is the thread of Benjamin Britten’s “Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra”. On a film post, someone asked what that was doing in the film. I replied to the query, stating that, the Britten work was a popular piece taught by General Music (what’s that???) teachers throughout the USA in the 1960s–the time period of the film. I wonder how many ‘General Music’ classes still exist (they do in my town, fortunately!), and if the Britten is a chosen work for the young students in 2012.

Jeffrey, with all respect, I think it’s a common but wrong opinion that branding is, by nature, shallow or slick. Not so. If you become known as an artist for whom music is more important than personality, than that’s your brand. And you can learn how to focus that brand, so people perceive you even more clearly this way, and are even more strongly attracted to hear you perform. Take one of my branding workshops, and learn how you can do that! (OK, end of commercial.)

The irony, though, is this. If you succeed in drawing attention to music rather than personality, because that’s your brand (and people are attracted to you because you do that), then in fact people are being attracted to _you_. As a person. You, the person who feels as you do, become the gateway through which people learn more about focusing on music.

So I fear that you can’t escape this. Anyone who’s attracted to anything you do as a musician, is in the last analysis attracted to you. Rather than deplore this, or try to evade it, I think you should celebrate it, and learn how to use it to do an even better job of serving the music you play.

Richard Dare, the CEO of the Brooklyn Philharmonic, has been writing extensively on the Huffington Post on this very point (“…the only way to make the audience younger….is to bring the cultural changes into classical music”) and, in his day job, implementing his ideas.

Richard’s doing wonderful things, Leonard, both in his posts and with his orchestra. Quite an exceptional man in every way. I’m happy that he and I have met, and become friendly. I’m eager to see what he’ll do next!

An additional thought on the shift: As parenting begins later, and more people put off having their kids into their 30’s, I would hypothesize that you might see the “parent drop-out” shift from people in their 20’s (who can now still attend music events for just the cost of a ticket) to people in their 30’s (who often more than double the cost of a ticket to cover babysitting, so drop out of attending all but a very few arts events as a result). A related challenge to getting younger audiences will be getting Gen X and Y audiences to “come back” post-young-child-raising. Thanks for this series; I’m finding it very thought-provoking and useful.

HA, you’re not the only person bringing up this point. But as I think about it, if people having children later affects the age of the classical music audience, wouldn’t the audience have been younger in the past than it is now? If, in the past, parents in their 20s didn’t go to concerts, and now it’s parents in their 30s and even beyond…

As I mentioned in reply to another comment, there are surveys from the past that show (a) an audience with a median age of 35 or even lower (depending on the survey), and (b) a large number of people identified as “housewives.” Should we assume these women were older, with children who’d already left home? One survey, of the symphony audience in Minneapolis in 1955, shows that 23% of the audience were “housewives,” and that 1/3 of them were under 35. The dominant age group in the audience was 21 to 35 — that was over 40% of the total.

Hi Greg,

Your data is very telling, and certainly causes concern for the long-term viability of classical music. I do have a question though: why should we only focus on building a younger audience instead of building a larger audience from those age groups that would be more likely to not have the barriers of disposable time and income?

I live in the small budget orchestra world, where we thrive on a large subscription base that also contributes above and beyond the ticket price. We’ve been having some great success in attracting patrons as classical series subscribers and are starting to turn the corner on getting a good portion of those patrons to buy in even more with a contribution.

I suppose that if we could attract a substantial group of young people over time, that could eventually pay off, but would it not be more beneficial now to target those empty nest-ers? From what I know of the national statistics, approximately 10% of the population claim to enjoy classical music, but less than half of that attend concerts. Why limit our efforts to young people only?

Thanks for the great post!

John, that’s a good point. I think the trouble with targeting empty-nesters is that it’s a good short-term strategy, but not a good longterm one, because (if I’m drawing the right conclusions fromt the data) fewer and fewer of the empty-nesters will respond to your marketing as time goes on, and more and more grew up in our current culture.

Also, the word “young” has a wistful meaning in classical music that it might not have elsewhere. In our world, anyone under 50 might count as young. I know classical music professionals in their 40s who say that their friends of that age will never go to classical concerts. So that age group, too, could be a target — if we could figure out how to get them in.

Beforehand I want to apologize for the weak English of mine. Possibly, I did not understand clearly the article, because of English. Anyway it was the interesting reading on the worrying topic. Thanks. This is my answer to this article.

Please, don’t! Do not make changes in to classical music and make the poor composers to turn over in their graves! From this notice already clearly, that I do not agree with the author of this article. And furthermore, I think the measures, which he propose more scare me, than just let this many centuries musical culture be in almost oblivion.

Firstly, his base for counting number of people who involved in classical music is totally wrong. He counts only those who attend the classical music concerts or Opera Theater. Therefore his conclusion about the reasons of reducing amount of people who know classical music and love it is also wrong.

Take me like closest example. I have been not attending to any performance of classical music since end of Soviet time in my country just because of money. But it is not means that I am out of audience of classical music. I have a classical musical education and may say I grew up on classical music, in the walls of Novosibirsk state conservatory and Novosibirsk state theater opera and ballet actually. I had been not playing the piano more years in my life, than I was learning in the state musical free school in my childhood. But as only I have got an opportunity to have the instrument, I have started to play again and recreated my musical program and went further. So, I am more, than just the one of audience of classical music. I am a classical music person. My example is not an exception. I sure, that the entire count of classical music audience would be quite bigger, if it was more available for simple hard working people and especially for theirs children, the more to give them free musical education.

So, it is always and still about inequality in our society.

Secondly, the author speaks about culture changes and “irruption of black culture into the white mainstream”. Nothing has propelled people out from classical music and has reduced number of admirers of Mozart, for example, because of appearance the rock and roll and it influence. I see other “black roots” in these changes of cultures. By my opinion there two real reasons for reducing people who know, at least, classical music , even by names of greatest musicians like Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, not theirs music.

One reason it is truly changes in culture in direction of culture of consumption. You clearly understand, what I mean, if you recall “145 degrees by Fahrenheit” of your brilliant, recently passed away, writer Rey Bradbury and our Russian brothers Strugatsky with them humorous story about how scientists grow up in laboratory “the super consumer” and when they let him out for a minute was a big burst during which the many things instantly disappear from people around and the several observers of experiment discover that even the gold dental crowns disappear from their mouths. This domination the culture of consumption has been having a heavy influence on quality of education. Educated person stops being equal to an intelligent, cultural and erudition (reading) person like it was in past. Precisely this I mean, when I mentioned above about the people who do not know such names as Bach and Beethoven, but graduated university.

Other reason it is one of consequences these general changes of cultures directly in side of domination of culture of consumption, but which relate with the developing countries which were in past centuries or more recently as the colonies of rich European countries like France and England, for example. By my opinion the trick was that university education in such countries is given on English. For example, a future doctor or an engineer in India should graduate university on English language and a whole high education is based on English. So, by my own personal experience of communication with such people they are away from his national culture, I mean not appearance or image, I mean by knowledge national literature and music (folk music), and therefore moral orienteers in life – culture one word, and in same time by graduating university they did not get the real English or European culture, because theirs education is aimed only technical side of it. As example, I can say about one doctor from India who was brilliant in medical area and who has shocked me with his absolute absence in any other area of life including partially the politeness, what should give a good nurture and education, is it not? When I said about Bach, he watched in Google about who is he. When I mention the novels of Charles Dickens he remembered that he had read only “Oliver Twist” on early courses of university only as necessity by program. So, all world around was for him like empty space and he feel herself quite comfortable in such world and do not feel need to be more erudite, to be more cultural. So, if there are some black roots in white mainstream that it is. Although, I do not sure that any doctors like doctor Preobrazhenskii, the hero of Michail Bulgakov in his “Heart of a Dog”, sometimes attend the Opera Theater and can whistle the aria from “Aida” by working above some scientific problem.

Finally, I can say that considering the question about reason reducing the audience of classical music, because of culture changes without analysis of a whole picture with what exactly nowadays means to be cultural and educated leads to wrong conclusion. Classical music, whether it is music of the truly passions in invention of Bach or breathtaking by incredible beauty “Arabesque” of Debussy takes whole of you: your mind, your soul – you cannot do something else except listening. Nowadays people mostly have not time or needs just listening , we all in hurry. More soulless world needs more soulless music.

About me personally, I have been not playing the piano since last month, because I have decided to spend all my free time for preparation to IELTS exam. Unfortunately, I have just a few free hours and not even daily. I work all the time. So, the very limited doctor from India with his rational life position temporary left last word in our discussion, because he advised me about this measure to reach the exam about year ago. The point is that for him music was nothing, not a value at all, for me is what I need like water, what I want to do, if this is last day of my life.

Sincerely

Whether or not I agree with Natalia says, I’m greatly honored by her comment. She has taken enormous trouble to write — with passion and force — so many things she feels deeply about, in a language that isn’t her own. I respect that tremendously.

My own view would be that there really are, very roughly speaking, two cultures at play in what I’ve been writing, and in what Natalia writes, an old culture and a new one. Natalia writes with such feeling about the loss that people brought up and nourished by the old culture feel, when they see that a new generation of people don’t share that culture, and don’t even know the names of some of its greatest artists. I’ve known many people who share that dismay.

I can’t speak of how things might be in Russia, but at least in the US (and certainly in Britain, and in European countries) the new culture has its own depth and literacy. It would be lovely if, someday, Natalia could meet someone from this new culture who has deep artistic taste and deep intellectual knowledge. Which is to say taste and knowledge of things in the new culture. Then, perhaps, a fascinating discussion could happen. But I do sympathize with the dismay of people who might see only one side of this cultural divide. Thanks again, Natalia, for taking so much trouble to write your comment. While anyone can see that English isn’t your native language, you write it with power and clarity.

Greg,

I couldn’t agree with you more and I look forward to hearing your thoughts on this topic in the future. I’ve been saying the same thing for quite some time. I am very interested in the way individual musicians will take responsibility for innovation in performance presentation that is geared toward building new audiences. I think you have hit on the right question, not when, or why– but how?

Thanks, John-Morgan. If you have any thoughts about how, or about musicians who’ve found their own ways of doing what we’re talking about, I’d love to hear what you’d have to say.

I think that this video proves your comment of making music more fun. We don’t need to change the glorious music, just how it is presented. Rather than trying to bring the people to a stuffy concert hall late in the evening, bring the music to them:

http://www.youtube.com/watch_popup?v=GBaHPND2QJg&feature=youtu.be

This is lovely, Joanne. And fun. It would be useful to ask how the impulse in it can be sustained, or scaled upward, so that the people who seem so charmed to encounter musicians gathering and playing in a public square would want to see the same musicians often. And, most crucially, pay to see them.

These are serious questions. Until they’re answered, we run the risk of having events like the one in the video come off as stunts. You can do them once, but then what?

I also have qualms about calling our music “glorious.” This is so much our word, our point of view. What if others don’t share it? What if they have their own words for the music, their own concept of it? We tend to think that because we think the music is glorious (or pick some other favorite adjective), this quality is actually inherent in the music, and therefore that others will quickly pick up on it, and say what we say, if only they’re given proper exposure to all that glory.

But is this really so? If you read a book like Robert Coles’s celebration of Bruce Springsteen (Cole being, for those who don’t know the name, one of the preeminent psychologists in the US, and one of the most deeply honored and humane of American intellectuals), you find that the people he talks to about Springsteen are looking for very different qualities in music. Something more earthly, more penetrating, and (if you can believe it) more inspiring than glory. So how would our “glorious” music speak to these people? They’ve spent their adult lives feeling that Springsteen’s music is like a second skin to them, an art that tells their story and their country’s. Our concept of glory might seem distant and abstract, compared to that.

Greg,

I particularly like your comments about the word “glorious.” I fell into the same trap as too many arts marketers by using the descriptive that popped into my mind hearing Ode to Joy. Of course, each person has individual reactions to music, as well as to many products. That is why Nike’s tag line “Just do it” is so ideal: “it” can be anything each person wants it to be.

As for how to build on a very effective flash mob experience, how about the following:

After the piece is over, invite listeners into the performance hall, which happens to be right at the same plaza.

Perform one or two other short pieces, so people will get the experience of listening in the hall and hearing more variety of musical periods/genres.

As people leave the hall, give them vouchers for low priced tickets to a full performance, preferably offered at the same time of day. The price should depend on the locale, typical full prices, etc. I’d guess that $10 for adults, $5 for youth is a good place to start. Make these special offers for certain concerts only, focusing on “entry level” music that might even be familiar and avoiding more complex and difficult sounds.

Then have follow-up offers for these people to keep them coming back.

Of course, it is crucial to collect their email addresses and other contact info the first time they come into the hall!

Joanne

Very fine, Joanne! Thanks for sharing ideas which I’m sure, in other contexts, people pay you very well for. And such good ideas.

I’d extend what you say, about collecting email addresses and staying in touch. I’d think it’s important to have things coming up constantly for the people on the email list to participate in. We don’t want to keep them passive!

Not that you don’t know that. It’s just something I’ve been caring a lot about lately.

Very interesting and not unexpected. So I wonder what the Vienna State Opera house is doing to have record breaking season as reported here: http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5hCdB2MrswIK3C4wNzPotVip5fDog

Are they implementing ideas that you have presented on this website? Does anyone know the details behind this story?

Hi, Matthew,

A brief news story like this tells us very little. One thing to remember is that the Vienna State Opera is a tourist attraction. Proper marketing attention to that is worth its weight in gold. Though of course we don’t know what the VSO administration may have done to get their numbers so impressively up, other than to reemphasize ballet.

In my experience, these numbers, for any given institution, rise and fall. And even in a generally unfavorable climate, you find some institutions doing well. It’s the standard bell curve, after all. What we’re seeing now, though, is that the hump in the middle of the bell curve has shifted to the right. That is, the bulk of institutions are doing, on the average, worse than they used to. That doesn’t mean that some aren’t on the top, still. But the ones that aren’t on the top are, again on the average, doing worse than they used to.

I think that we need to move into a new genre of music. Like from Baroque, Classical, and Romantic. It is time to move on. Baroque style was very structured, specific, and at some points rather dark. Classical was more up beat, happier, and had a key characteristic of spiccato bowing for the string instruments. Romantic was all about conveying emotions of a hard life and having the extremes of a dark side and a happy side.

But what was contemporary? To me it seemed to be about a fast paced society, something that was always on the go, fast, and busy. Sure that’s great music, for the 20s-40s, but now in 2000’s society is starting to slow down. People are taking the time to sniff the roses, where they deem worthy.

I’ve contemplated a new genre of music for quite a while. People tend to love soundtracks to movies. Maybe because the movie was touching, or maybe because society has switch to that type of music. What I see is movie soundtracks is one specific emotion being portrayed. It is an intensified type of Romantic music. One emotion but with the feel of contemporary. Contemporary composers have tested and succeeded with many pieces which contain a controlled dissonance. I feel the new type of music will have this controlled dissonance and at the same time have the heart melting passages which people adore from movies.

Dear Greg,

Just about all conductors were performing Schoenberg etc E.g

18/08/1960, Royal Albert Hall, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, John Pritchard, Elise Cserfalvi. Notes for Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto in E minor; Schoenberg, Variations, op.31

13/09/1960, Royal Albert Hall, BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Chorus, London New Music Singers, Malcolm Sargent, Norma Procter, Graham Treacher. Notes for Schoenberg, De Profundis (Psalm 130).

25/07/1961, Royal Albert Hall, London Symphony Orchestra, John Pritchard, Tamas Vasary. Notes for Beethoven. Symphony no. 4 in B flat major, op.: Schoenberg, Verklärte Nacht, op. 4

18/08/1961, Royal Albert Hall, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Malcolm Sargent, Eugene Goossens, Tibor Varga. Note for Beethoven, Overture Coriolan, op. 62; Romance no. 1 in G major for Violin and Orchestra; Symphony no. 7 in A major, op. 92; Schoenberg, Violin Concerto, op. 36 and so on….

The notes were by Hans Keller who along with Alec Robertson, Egan Wellesz, Hans Redlich and others were dominating the BBC Third Programme and were making inroads into the wartime dominance of Vaughan Williams and Sir Arnold Bax. It was agreat time to be alive. Yet the generation before me resisted progressive classical music because it demaned close attention and preferred the easy harmonies of the Bee Gees etc, It was their advocacy that allowed popular music to dominate. What is in decline is the idea that music should be demanding and that sounds should be strange and unfamiliar. Only composers like Terry Riley and Steve Reich come anywhere near such a level of challenge. When something becomes extinct, it is because a new form of life threatens its existence. At no stage in the history of musical culture has popular music dominated the temple, the synagogue, the cathedral,. the Mosque and the Concert Hall until now. You are an amicae curae for the decline of classical music. Though I am grateful for the opportunit for dialogue your eloquence has created. has created

I hadn’t realized that you’re British. My apologies. I have no idea what someone British might have heard on a crystal radio, so long ago. In the US, Schoenberg wouldn’t have been found.

I wrote a reply to you that I now think was intemperate. So I’ve replaced it with what follows. Strongly expressed, I know, but expressed (or so I hope) with some compassion. Here’s what I now would like to say:

Your new comment makes me very sad. It’s as if you and I are calling out to each other over a great abyss. You say (elegantly) that I’ve become an amicus curiae for the end of classical music, or in other words (for those who don’t know the term) someone making arguments (as if like a lawyer adding her voice to an existing court case) that will support classical music’s death. My own view would be that you’re serving as an amicus curiae — and please forgive my bluntness — for ignorance. There’s a vast scholarly and critical literature on pop music. I would imagine (and please correct me if I’m wrong) that you may not have read any of it, and may not even know it exists. In this literature are many rebuttals of your rather blunt assertion that true culture has been replaced by junk.

A year ago, I took part in a formal debate at the University of Cambridge in your country, joining skilled debaters some of whom, I’m sure, could have taken either the affirmative or the negative of the proposition that we pondered. That’s because they knew the subject. You, I fear, couldn’t, in a similar setting, defend either the affirmative or negative of your “junk” comment, because you don’t have information that could support either side. Very much including your own. Your assertions here, I believe, are essentially faith-based. You believe them utterly. While to me, they’re the equivalent of standing on a mountain, and crying out, “The sun is green!”

But I fear you can’t see why I would say that.

Let’s allow you to assert your point, even so. Culture has been swept away by junk. What now do you propose to do? My view, I’d think, at least offers hope. The culture that used to be unchallenged has been partly swept away, but by another culture just as valid. This culture is marked by, among much else, a great open-mindedness and curiosity. (If you knoew much about contemporary pop music, and had listened, to cite an obvious example, to Bjork, you’d know that a yearning for strange and unfamiliar sounds is one of the great hallmakrs of some areas of pop music today.)

Therefore the old culture can easily assert itself, as long as it acknowledges that times have change. I’d think, again, that this is a hopeful point of view. Is there any hope that you can offer in its place?

Dear Greg,

Allowing me to assert my point makes it not a question of academic respectability, which seems to be a sore issue with you, but of common sense. If the ethos of popular culture could help the plight of classical music then it would have done so. Your argument seems to be that in some way it can. My argument is; why trust a movement that didn’t help classical music in the immediate past. My grounds for hope lie in the respect and dedication of Japanese, Chinese and other non-Western clivilisations to a once-Western tradition that has now become global and therefore new. Roll over McCartney!

The death of any form of music occurs when it becomes to culturally introspective.

Classical music in our era is not accessible because those who are dominant in the culture have made it that way.

If you want classical music to survive then the culture must be opened up to remain both innovative and accessible so that new participants are willing to make the connection.

To understand how, I feel you must study and understand other western music cultures, including pop music but also the rise (and fall) of various electronic genres. It is ironic in a way that those who embraced the former avant garde music don’t even consider today’s highly technical electronic music at all.

One of the key points is accessibility. I’m not necessarily just talking about the accessibility of the music, but accessibility to the music.

These days young people such as myself can just listen to tunes uploaded by artists themselves on Soundcloud, or even watch orchestral performances on Youtube. Live music can be special if you feel the performance and orchestral music even more, but there won’t be broad support if performances of popular works are irregular and expensive.

There are other emerging trends, such as a rise in young people trying their hand at orchestral composition, inspired by orchestral film and game music aided by modern synthesis and sampling techniques. The immediacy of this technique means that there are those that do not receive any formal music training at all (though they may still learn music theory from other sources).

Here are some future trends to be aware of:

In terms of performance, there is something that live music can deliver that recorded music cannot – variation or improvisation. With electronic music readers, there is no reason why algorithmic variation cannot be built in to the composition itself – imagine a composition that is unexpectedly different each time it is performed.

I daresay electronic music itself will move in this direction too, as computer chips become even more ubiquitous. Someone is probably writing algorithmic based tunes with built in variations to run on mobile phones right now.

The other side of accessibility is actually involving your audience, let them choose what is to be played. Even let them play a role in the composition process, I wonder how works by classical composers, eg Beethoven could be ‘remixed’ by a group of people for example?

In the past the classical tradition continued to grow with new ideas so why not now?

Greg,

Apologies if you’ve already addressed this and I missed it, but what is your take on Mark Stern’s analysis of age and generational cohort in the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts? Analyzing the same dataset as you (though looking beyond classical music), he concludes that age and cohort are far less important than you seem to give them credit for, once you account for other factors. http://www.nea.gov/research/2008-SPPA-Age.pdf

Hi, Ian,

Thanks for mentioning this. I’d read it, but forgotten it. I think, to be honest, it’s a silly effort. Reminds me of the Japanese salsa band, whose members had learned salsa tunes from recordings. They came to NYC to perform, and discovered something they’d never known — that salsa is dance music. Similarly, the author of that study seems to be locked in a dark room, staring at numbers without much sense of what they mean in real life.

The first big sign of trouble is this: “To an arts administrator who sees the average age of her audience increase year after year, it does matter, even if what she’s noting is simply the general aging of the population.” The median age of the US population in 2010, according to the Census Bureau, was a shade over 37. Meanwhile you have orchestras with a median audience age well over 50. And Peter Gelb, just a few years before 2010, saying that the average age of Met subscribers (I think he said average, rather than median) was 65. How can someone say these audiences aren’t — first of all — older than the general population? And that there must be some reason for that.

Second, in 1955, one study showed that the audience at orchestra concerts in Minneapolis had a median age around 35. That’s about 18% higher than the median age of the population then. If we figure a median audience age of 55 now (not atypical for orchestras), that’s 149% higher than the median age of the current population. Of course these statistics need to be refined, because the median age of the population includes infants and children. We’d need to know how their proportions in 1955 differ from what we see now. But we can track other data points — even younger ages for the orchestra audience in a 1937 study, a slightly older age in 1966 — and still see the median age for the orchestra audience now having increased, as a percentage of the median age of the population generally. There’s a steady increase from 1937 to now.

The NEA figures that this paper uses also are tricky, where classical music is concerned. The NEA gives a lower median age for the classical music audience than we see at major classical music events. That’s because their median age is calculated by asking people (during the census, and in other surveys) if they’ve gone to classical performances. A “yes” answer might be a community orchestra (where the median age is lower than at large professional orchestras), or a Fourth of July concert in a park. So the author of this study is working with figures that are too young, if he wanted to talk about what large classical music institutions see.

There’s also his reliance, most of the time, on aggregate figures for arts participation, which is a very different animal from classical music ticket-buying.

He’s also talking about age as a predictor of arts participation, and finding that education and income are going to be better predictors. But that’s easy to explain. Even if Met Opera subscribers have a median age of 65, meaning that half are older (!), half also are younger. Some will be in their 20s and 30s. But it seems safe to say that almost all will be above average in education, and (some of the younger ones apart) in income. So then income and education become better predictors, in that you find fewer people with low education and income than you find young people. But that’s not relevant at all when you ask — as I’d think you’d have to — why the age of this audience has increased so greatly.

In fact, I’d venture a guess: That in 1955, too, the opera audience was better educated and had higher incomes than the general population. Perhaps to the same extent, or maybe even a greater extent, than it does now. But it wasn’t all that much older. The biggest change, in these three measures, has been in age. The opera audience is still better educated and more well off than the average American, but is now quite a bit older, too. That makes the age and income figures relatively trivial, if we want to ask about changes, and what the changes mean.

Further, just look around. I’m picturing the audience at a National Symphony concert at the Kennedy Center in Washington. Anyone — anyone at all — looking at that crowd, would instantly peg it as upscale, yes, for sure, but also old. Notably older, for instance, than the fans at a Nats game, or the people you see at the movies. Or at the Lucinda Williams show I went to at Wolf Trap last summer. (Which was not a young crowd.) Or, more simply, than the people I see on the street, either downtown or in my Adams-Morgan neighborhood. If you’re juggling numbers, and your numbers somehow fail to miss what your eyes so obviously tell you, something is wrong.

Finally, let me cite an email I received from the former director of one of the most famous, most artistically significant performing arts organizations in the US. I can’t say which one, because the email was private. But this person wanted emphatically to second what I’d been saying, and offered stats to back it up. The organization in question — a household name in the performing arts — saw a slow but steady drop in subscription sales, along with failure (in truly astonishing proportions) to get single ticket buyers to come more than once.

And who were the subscribers? People who’d been coming for decades. The audience, in other words, was old. Its core members had started coming when they were younger. There were fewer and fewer of them every year. And they weren’t being replaced by an equivalent number of younger people.

Which is exactly what I said is happening. I think if you look at the actual experience of performing arts organizations, you find a picture much more like what I described than what the author of this misguided paper thinks is going on.

And one other point, Ian. Though the paper doesn’t concentrate on this, there’s mention of arts education being a predictor of attendance.

But that’s the same thing as saying that age is. Because the people with the arts education — if we accept that there’s been a collapse of arts education in our schools in recent decades — are older people. The correlation may cross age boundaries, maybe, but still for the most part the people with arts education are older. So age remains quite a large factor, and the arts education puzzle piece then might become useful if we wanted to explain why the audience has become so old.

(I should add that I don’t find it so significant. A correlation doesn’t necessarily indicate causation. In long-past decades, for instance, more people were taught about classical music in school. But it’s also true that classical music was far more popular. So maybe the causation goes in _that_ direction! The popularity of classical music led it to be taught in schools. Rather than, as many people suppose, classical music teaching in schools was what made classical music popular.)

‘Classical’ music, for want of a better word, hasn’t been dying for the last 60 years because of its lack of innovation, but quite the reverse. It began to kill itself when concepts outweighed musical content – works of the ‘Sonata for pebbles in a bucket and dripping water’ variety, causing millions of people to leave the concert halls and buy rock and roll, music which had recognisable tonality and accessible meaning. This avant-garde approach, while interesting for its historical significance, is even now the mantra of far too many music professors, who continue to champion the most experimental music as if it was imbued with freshness. Haven’t we put the 1950’s behind us by now?

Nor will we attract the next generation by slipping in a token Hip-Hop drum beat! Please consider that the ‘progressive’ priests who slip on a guitar, because they feel that something like ‘Michael Row The Boat Ashore’ will capture the musical hearts of the young when ‘Dear Lord And Father Of Mankind’ has failed, are generally replacing the music of the 1860’s with the music of the 1870’s!

I frequently despair when I hear yet another pseudo-intellectual making the case that an element of youth-culture is the magic panacea that would surely reinvigorate classical music. And I never hear the case made but that it involves a relaxation of the rules, a virtue being made of lack of rigour, a ludicrous argument that it ‘makes classical music accessible’ to those who are not musicians. If too many of us continue to delude ourselves that musical technique is no longer required, and that participation in music-making needs to involve non-musicians to survive, then I propose one or two initiatives that might put this thinking into context:

My first proposal would be that construction work should regularly be carried out by those individuals who are unable to build a wall. This would, of course, make construction more accessible to those individuals who find the current trend for walls with structural integrity just a little too elitist. Likewise, how much more we would appreciate the complexities of our hernia operations if we could be reassured that even the most cack-handed of the population was empowered to have a go.

Secondly, I am minded to enter the Wimbledon tennis next year with my new and exciting approach – I always take care not to hit the ball, as that would smack of yesterday’s thinking. Just as hitting a recognisable tonality would be frowned upon in thousands of music departments, my new non-contact approach to tennis abandons the constrictions of the old ways.

In my decades of work as both a classroom teacher of music and as a composer, I can reassure those with concerns about the classical sensibilities of the next generation that children show equal delight when a violin sonata is performed in front of them as when they are treated to a virtuoso rock guitar solo. It is the quality of the performer that they appreciate, not merely the contemporary nature of the piece. And those who would update classical music to keep it popular are contributing more than anyone else to the demise of the genre, through indiscriminate assimilation and homogenisation. The inclusion of a string section doth not a classical piece make.

And the experimental nature of my tennis playing doth not an exciting spectacle make. When the crowds abandon Wimbledon, I’m sure that some helpful individual could contribute to a forum like this one and advise me that the public would surely return if only I could accompany my avant-garde non-contact tennis playing with some songs by Justin Bieber.

A very personal response to this: Sometimes I despair of these discussions. I have no idea who J. Gyffrydd might be (apart from possibly being Welsh), but I suspect he’s young, and I know he doesn’t check facts very carefully.

“‘Classical’ music, for want of a better word, hasn’t been dying for the last 60 years because of its lack of innovation, but quite the reverse. It began to kill itself when concepts outweighed musical content – works of the ‘Sonata for pebbles in a bucket and dripping water’ variety, causing millions of people to leave the concert halls and buy rock and roll, music which had recognisable tonality and accessible meaning.”

This is made-up history. I went to classical concerts in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, and once in three blue moons you might encounter pieces like that on programs. But overwhelmingly the music was familiar — Mozart and the other greats. And nobody fled concert halls. The audience kept coming. What was new, however, was that younger people stopped joining the audience. If we’re going to blame repertoire for that, it would have to be Brahms and company that kept the young people away, because — overwhemlingly — that’s what was being played. Yes, there were a few atonal contemporary pieces by familiar names (Boulez, Carter, whoever), but again, only a couple of times in each season. Not nearly enough to drive people away. I once facilitated a discussion with members of the Cleveland Orchestra audience. The Cleveland Orchestra might have done more atonal new music than other American orchestras, but the audience members I talked to — while making it clear that they didn’t like the new music the orchestra played — had all kept coming. And never mentioned anyone fleeing the concerts.

“I frequently despair when I hear yet another pseudo-intellectual making the case that an element of youth-culture is the magic panacea that would surely reinvigorate classical music. And I never hear the case made but that it involves a relaxation of the rules, a virtue being made of lack of rigour, a ludicrous argument that it ‘makes classical music accessible’ to those who are not musicians. If too many of us continue to delude ourselves that musical technique is no longer required.”

Of course I’ve never said any of these things. There isn’t any magical panacea, though there are a few ideas that have been shown to work. Some people do neglect the technique that classical music requires — as when, for instance, years ago, an opera company commissioned an opera by Stewart Copeland of the Police, who didn’t know how to write classical music. But I hate things like that. Instead — thinking back over what I’ve written here — I’ve praised by Brooklyn Academy of Music for giving Sufjan Stevens a chance to learn how to write for symphonic instruments, before writing a symphonic work. The results speak for themselves. He really learned how to do it. And I’ve praised Mason Bates, one of the leading younger composers in the US, who’s also a dance DJ and writes pieces (for the YouTube Symphony, among others) in which he’s a laptop/turntable soloist. But he’s an expert orchestral composer, with a Master’s Degree in composition from Juilliard. He was also picked by Muti to be composer in residence for the Chicago Symphony.

And I’ve praised Derek Bermel, who orchestrated Mos Def songs for the Brooklyn Philharmonic. He, too, is an accomplished orchestral composer, and in fact came to fame when his clarinet concerto was premiered by the American Composers Orchestra. Everyone could instantly hear how solid his composition technique was.

I’ve praised these people — and others, including Chris O’Riley for his cello/piano arrangements of Arcade Fire and Radiohead songs — precisely because they have terrific classical technique. So funny, then — and sad — to see J. Gyffrydd popping up here with no knowledge of what I’ve said. To use his own analogy, it’s as if he showed up at Wimbledon carrying a cricket bat, unaware that the game they play there is tennis.

Hmm. Don’t assume it was an attack on you Greg, you weren’t the ‘pseudo-intellectual to whom I referred, nor was it one of your comments which provoked my ‘panacea’ reference.

I can only put your dismissal of both my opinions and myself* (no, I’d never heard of YOU either) down to your perception that I was directing these comments at you, perhaps it caused your charm to slip away a bit!

Justin

*J Gruffydd Edwards, award-nominated jazz pianist and composer (BBC, Channel 4, Ballet Rambert, Radio France etc etc). And fully 45-and-a-half years old, as a matter of fact!

Justin, you come into the comments section of my blog, firing off a broadside from 100 guns. You don’t say anything about it not being aimed at me. So who should I think it’s aimed at? If you’d given examples (as I certainly could) of dumb things you don’t like, then I could understand what your focus might be. But as it is, why shouldn’t I have thought you were talking about me or my ideas? Why else would you post the comment, in response to one of my posts? You didn’t like something I said, and fired away. Not the best communication tactic, if you’re later going to say you didn’t mean me at all.

One other thing about your comment: I’d take very strong issue with your characterizing of pop music as “youth culture.” At least in the US, it’s nothing of the sort. It’s a wide spectrum of things, some with quite an older audience. How old do you imagine the crowd at a Bruce Springsteen concert is? Not young. He himself is 62. Every study of the arts audience in the US (and, as far as I know, in the UK, too) shows that almost everyone, of every age, is an omnivore, as the term goes, absorbing both high and popular culture. i’m trying to get the classical music world to understand this, and to make itself part of the larger culture, rather than stand apart from it. That has nothing at all to do with youth culture, above all since the younger audience talked about for classical music in the US would be an audience under 50.