In the chunk of my book I posted here, you’ll see I talk a bit about Christopher Small, a man we can’t honor too much. I was saddened to learn that he died last week, aged 84.

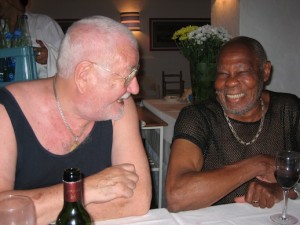

I wish I could find another photo of him I once had, sent to me years ago by a friend. On the left is that photo, showing Small and his partner, Neville Braithwaite. Radiating joy. (My friend read the post, and resent the picture. Thanks, Susan!)

Small was a profound and humane writer and teacher, whose three books are essential reading for people who care about classical music’s place in the world. Here are links: Music, Society, Education, Music of the Common Tongue, Musicking. Does “musicking” seem like an odd word? It’s the key to Small’s thinking. Music, he said, was an activity, something we actively do, and do as participants, whether we’re making the music or listening.

All by itself, this idea is a deep critique of classical music, as we’ve known it. Because in classical music thinking, music consists of musical works, objects, notated scores, which then — in a step down the food chain — are performed. The notation, the work, comes first, the performance second. Small couldn’t agree, and in his books, he examined the culture of classical music, comparing it in Music of the Common Tongue, for instance, with the culture of African-American music, which he found more joyful, a culture that created a sense of community.

For a sample of what he wrote, you can read a chapter from Musicking that I’ve sometimes assigned to my students. It’s about classical concert halls, and what they imply about the role of classical music in our world, and about the relationship (or lack of it) between musicians and listeners.

Here’s a link to Small’s obituary in the New York Times.

But I’ll end with something else. Before Small died, while he lay ill, I was one of a group of people asked to write an appreciation of him. The idea was to show him what we all wrote, to bring him some joy, in his last days. I was touched to be asked, and so happy to do it. So that’s what I’ll end with. Here’s what I wrote:

I first heard widespread talk of a classical music crisis in the last half of the 1990s. I’d been out of classical music for a number of years, working as a pop music critic and then as music editor of Entertainment Weekly. In the ’80s, writing about classical music, I’d raised some alarms about how out of touch the field seemed, and so, in different ways, did Susan McClary, John Rockwell, and a few other lonely souls.

But when I left Entertainment Weekly in the ’90s, and returned to classical music, things had changed, and now there seemed to be widespread concern. I remember a marketing executive at a classical record label telling me that he’d banned the word “art” from his company’s ads and press releases. Had to reach a larger audience! The New York Philharmonic unveiled a group for teenage fans to join, urging them to learn that classical music could be just as much fun as classic rock. (Completely unaware, of course, that teenagers back then never listened to classic rock, which was their parents’ music.)

And since those days, the deluge. Declining ticket sales, funding crises, no more classical music critics at most newspapers, the Philadelphia Orchestra goes bankrupt. And, what’s most important, young classical musicians bursting out with new ways of doing what they do, opening classical music to the world outside.

I hope those young musicians delight Christopher Small, who when he published Music, Society, Education in 1977 started down this track before any of the rest of us did. As they open a path to a humane and sustainable future for classical music, these young musicians, whether they know it or not, his musical godchildren.

***

I first heard about Small from a rock critic, Bob Christgau, in the early ’80s my editor at the Village Voice. I didn’t know about Music, Society, Education, and neither did Bob. But Bob was raving about Music of the Common Tongue, because it did something that no one at that time had done, or certainly not with such grace, depth, and erudition. And this was to put African-American music (along with its African origins) on an artistic par with classical music. And in fact to rank it higher, because it offers something deeper for humanity.

Of course Bob didn’t need anyone to tell him how powerful African-American music was. But to have it placed so high on a cultural scale that also included classical music was profoundly encouraging. Bob wasn’t, as I found at the time, alone among rock critics in sometimes wondering whether the music he loved might not be kid stuff. He didn’t know classical music. How could he be sure, then, that classical music didn’t hold some secrets that, if someday he woke up to them, would show him how trivial his life’s work had been?

Christopher Small sent that fear away. And did it, as I hardly have to say, for many more people, including me. Unlike Bob, of course, I do know classical music. And after I defected to pop, late in the ‘80s, I got to know classical music’s Other as I never had before. But even if I might have felt the difference between the canon and the Other — as, really, the whole world can — I’d never explained it to myself (let alone to whoever read my writing) as beautifully as Small did.

***

But there’s something else I want to talk about, something beyond precedence, and even depth. Two things that Small has written are, in his work, my touchstones. Music of the Common Tongue is one, and the other is chapter one of Musicking, “A Place for Hearing,” which I’ve assigned in courses I’ve taught about the future of classical music. I’ve done that for reasons those who know the chapter easily can guess — because it looks at the classical concert hall as if no one had ever seen one before. And therefore can (and with such clarity and ease!) teach us many things that might not otherwise be clear, not just about concert halls, but about the entire practice of classical music, as we’ve known it in our time:

There is wealth here, and the power that wealth brings.…Performers and listeners alike are isolated here from the world of their everyday lives.…Nor does the design of the building allow any social contact between performers and listeners. It seems, in fact, designed expressly to keep them apart.

It’s no surprise, these days, to find people who’ll make a similar critique, completely on their own, simply reacting to what they see, either in the concert hall, or in ways that it’s changing. When I was hired in the 2000s by the Cleveland Orchestra, to be (astoundingly, since other orchestras had done this much earlier) the first person ever to speak about music during a concert, from the stage of Severance Hall, someone from the audience saw me later on, and burst out, with impulsive joy, “You broke down the barrier between them and us!”

People in their twenties, surveyed years ago in Houston about why they didn’t go to hear the Houston Symphony, said (among much else) that it didn’t seem to matter whether they were there. Or whether anyone in particular was there. The performance would always be the same.

And the graduate students I teach at Juilliard have often said to me, so wistfully, “I wonder what they’re thinking” (meaning, of course, the people in the audience, people three times the students’ age). “I wish that they’d react!”

Which of course means that you don’t have to be Christopher Small — or to be even the slightest bit analytical — to feel the truth of what he’s saying. It makes itself felt, on its own. But Small gives the clearest, most comprehensive, and most helpful explanation of what so many people feel, showing why they feel it, and what the largest meaning of these feelings might be.

And one reason he’s so helpful is, I think, is because of the final — and most joyful — thing I want to note. “A Place for Hearing” isn’t a polemic. Nor is Music of the Common Tongue, or anything that Small has written. He isn’t angry, or dismissive (as, I fear, so many of the writers are who in these latter years have taken it on themselves to defend classical music). He doesn’t seem to want to make us angry, or to goad us on to action. Instead, he seems to want us to understand the deepest human implications of the things he sees, and to form our own conclusions.

Which makes his work more powerful than any polemic could be, and more inspiring. And more likely, I think, to lead to healthy ways of finding new directions. Often I find people saying that we have to bring classical music to a wider audience so that we can educate that audience, or else preserve something precious that’s threatened in our culture. Or, of course, to find new people who might give us money.

These reasons for reaching out seem, variously, shallow, to me, or patronizing, or opportunistic. ns. “We’re better, more artistic, than you, our future audience. But we need you, and so we have to learn to talk to you.” Which denies the humanity we share with our new audience, and denies our own humanity. And prevents us from understanding that we ourselves can learn from reaching out, and that by reaching out, we’ll change.

I said that young musicians who are changing classical music are Christopher Small’s godchildren. I want to be his godchild, too. As I teach and agitate about classical music’s future, I want to do it in his spirit — with openness to every possibility, and with compassion and generosity.

‘Music is a VERB not a NOUN – it something we do and it is valid at every level.’

I think sometimes music educators miss this point and place too much emphasis on teaching ‘songs’ or parts for concert performances and competitions. This thinking simply isolates and alienates potential music makers and is counter-productive on many levels. Making ‘classical’ music more important or valid than any other music is ridiculous. Music is music and we as teachers can do more to foster acceptance among our community of potential ‘musick-ers’ – and we should encourage musick-ing at all ages.

This is typical of everything which is wrong about music criticism today,with all due respect.

Why can’t people just accept western classical music on its own terms rather than judging it by the standards of other musics?

Finding fault with it just because it isn’t like the traditional music of Africa or other parts of the world is unfair. There’s a double standard involved here. People who try to defend western classical music are accused of being”snobs” and elitists”, but it’s perfectly okay to

denigrate classical music and condescendingly demand that it “change” from what it is in order to be more “relevant.”

No one ever demands that Rock music or Pop,or folk music etc “change” in order to be more like classical music. Any one who did this would be condemned as an “elitist”.

Dear Robert:

You haven’t read Chris’s work. He did not find fault with Western music — indeed, he spent hours each day playing Mozart sonatas. He just wanted to find ways of incorporating other kinds of music into the educational process and also reinvigorating the Western music scene. A student of Luigi Nono, Chris made better cases for Boulez et al. than most modernists do. The same things can be said of Greg, who also started as a modernist composer and who is trying to maximize the chances that classical music will survive its current crisis.

Thanks so much for this eloquent post, Greg. Chris Small’s ideas and perceptions have affected me deeply. I’m grateful to read that people sent him news of his impact, because I think he didn’t realize how many minds and hearts he touched.

I’d love to read the appreciations that were sent. Do you know of any plans to gather them up?

Thanks, John. I’d love to read the appreciations, too. I’ll ask about plans to gather them somewhere. I know that one is by Robert Christgau, and appeared on his blog. If I find out about more, I’ll post here.

I know Small wasn’t finding fault with the music itself, and I would definitely like to read the book .I Googled him and found out about the book at Amazon.com.

I understand the basic ideas he was trying to set forth, but I don’t agree with them.

To say that there is no such thing as music, but only “musicking” strikes me as preposterous.

This is like saying that there is no such thing as food, but only “fooding”.

I don’t think that there is anything wrong with traditional way of presenting orchestra concerts. Audiences still gain an enormous amount of enjoyment from them.

I have no problem with experimenting with alternate ways to present classical music, but I reject the notion that there is something intrinsically “wrong” with the way classical music is presented. There is absolutely no reason why people should not attend concerts by any of America or the world’s orchestras. If only ore people would just try them ! They don’t know what they are missing. Classical music has its problems but it isn’t broken and doesn’t need fixing.

Robert, your assertion of the noun-ness of music makes me think of Henry Kingsbury’s wonderful ethnography of a music college, ‘Music, Talent and Performance’. One of the really subtle things he points out is the way we talk about ‘the music’ as if it were a real object, whereas in fact in pretty much every context it’s actually a very abstract construct that says more about our shared values than the sounds themselves.

I think in some ways it’s a more nuanced critique of the idea of music as a noun than Small’s – but then I think part of what makes Small’s work so compelling is the way it is a constant surprise to re-think music as a verb. It does keep forcing us into mental double-takes.

Anyway, have a read of Small, and you’ll probably find you’re fighting back with him as you are with the summaries of his ideas here – but there’ll be a lot of really productive ‘yes, but…!’ moments in there too.

Liz, how lovely, the way you describe the effect of Small’s writing, and especially how Robert (a man who loves music very deeply) would fight Small’s work, and yet have “yes, but” moments. I admire your generosity, in how you’ve thought and phrased these thoughts. Thanks for sharing them here.

I would like to thank you also for the wonderful tribute. LIke John Steinmetz, I have been deeply affected by Small’s work. Is there any word on where “tributes” might be posted for Christopher Small? I wrote a short one that I would like to contribute, mainly about his influence on college music teachers like me.

Thanks.

Thanks, John. The Small tributes are at https://public.me.com/robertwalser. But I fear they’re not looking for new contributions. These were tributes written by invitation, and, for better or worse, the people who organized this aren’t in a position to take it further.