I’ve talked many times here about performance practice in the past — how musicians used to change the music they played, and how they often improvised their changes.

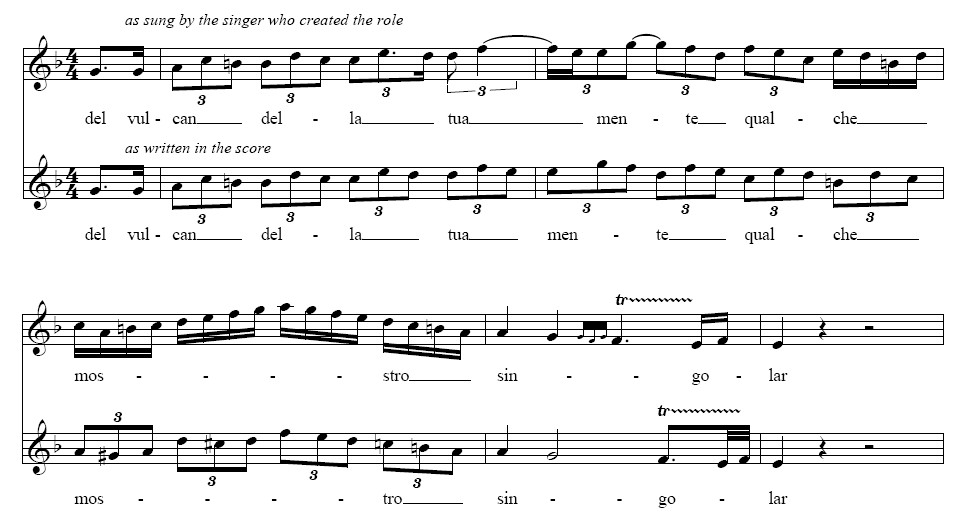

We know that, of course, and the standard word for what they used to do is “ornamentation.” What we don’t often hear, though, is how extensive those changes used to be. So here’s a striking example. It’s a passage from the Almamiva-Figaro duet in the first act of The Barber of Seville, as sung by Manuel Garcia, the tenor who created the role of Count Almaviva. It was published years later in a book, The Art of Singing, by his son, Manuel Garcia, Jr., one of the most famous voice teachers in the 19th century.

Notice how free the ornamentation is, and how exuberant. And how the rhythmic notation at the end of the first measure and the start of the second can’t possibly be exact. Garcia must have been really soaring at that point, singing things that notation can’t really capture. Note also that Garcia Jr. cites this as an example of rubato, which in the 19th century meant that the soloist varied the written rhythm while the accompaniment stayed in tempo.

And now imagine an entire performance, full of changes like this. Then imagine going to hear the opera again with a different tenor, who’d make entirely different changes of his own. We don’t have any experience like this today, and if I wanted to be fierce, I could say that we’re falsifying the music, which Rossini wrote fully expecting all singers to make their own changes.

Here’s what Garcia sang:

Footnotes: if we trust Garcia Jr.’s notation, the duet was sung transposed a tone down.

And I also should address something well known about Rossini, which is that at some point he got tired of singers making really bad changes — which of course happened — and started notating the exact ornaments he wanted them to sing. Yes, he did that. But it doesn’t preclude changing what he wrote. For instance, he’ll write the same highly ornamented passage twice in a row, knowing full well that nobody in the 19th century sang repeated passages without making changes.

So obviously he expected some changes. What he did, I think, was to limit the ballpark in which changes could be made, not forbid them entirely — which, as he would have known, was completely impossible. And also would have weakened performances, since one point of the changes was to take music written for one singer, and make it more suitable for others.

Here’s an example. Rossini’s wife, Isabella Colbran, was more comfortable, at least when she was with Rossini, in the lower part of her voice. So the role of Semiramide, which he wrote for her, is written very low. Another soprano, more comfortable in her higher range, would have said, in effect, “Well, there’s no point in my singing that! It wouldn’t sound good at all. So I’ll rewrite it to go higher” — which (in our own time) is exactly what Joan Sutherland does in her performance of the big soprano aria from Semiramide on her recording The Art of the Prima Donna.

So you’re suggesting that we could perform classical music similarly to how jazz musicians perform rhythm changes or other standards? Or how U2’s interpretation of “All Along the Watchtower” differs from Dave Matthews’ which differs from the original? I like it.

The biggest challenge with this, however, is that improvisation is almost completely restricted to jazz and rock in the 21st century. Classical musicians, by and large, do not improvise, do not play by ear, and in my experience possess a profound fear and dislike for improvising. I think going to concerts where this is the norm is the same as having an art gallery display nothing but paint-by-numbers watercolors of the masters. “Wow, you exactly recreated ‘Las Meninas.’ Congrats, I’m bored.”

The audiences, I think, would welcome variety and personal interpretation. It’s the musicians who are either afraid to do so because they don’t know how, or they feel it demeans the music they’re performing. It’s completely up to the performers to first learn how to improvise, and then to apply it tastefully.

Thanks for the post, and the historical context, too!

You hit on a lot of important points in this post and your response to the first comment, Greg.

One thing that led to the death of improvisation in what we now call classical music was bad improvising. Even back in the Baroque era composers were frustrated when singers and instrumentalists ornamented excessively or badly and sometimes suggested no ornamentation was better than bad, excessive ornamentation. Bach was criticized for writing out so much of his ornamentation, but it’s easy to see why he did it–and how great it is that he did! But the consensus seems to have been that the best-case scenario was ornamentation added by someone who had the skill and insight to use it to enhance the music, not distract from it. And that’s what you’re saying about Rossini, too.

The other thing is that the music has to invite improvisation for improvisation to be appropriate. Baroque music invites all sorts of improvisation, in realizing figured bass, in ornamentation, etc. Rossini invites ornamentation (done well, anyway). Jazz invites improvisation. Brahms doesn’t (seem to).

In much jazz, the subject for the improvisation is a standard tune, which in its original form as a song was completely written out. But the context was/is so different from classical music–Cole Porter expected arrangements and jazz improvs on his stuff. (And about the last version I want to hear of a Cole Porter song is Cole Porter singing it in its original form.)

As for jazz improvisation, I’ve read that Gunther Schuller has documented that solos that began as improvisations often become more and more set and repeatable. Improvisations often evolve into compositions, and that’s an aspect of the written-out nineteenth-century ornamentation you mention. Not everyone could improvise ornaments well, and needed to work them out in advance. But I’m sure there was also a practice in which ornamentation ideas presented themselves in improvisations and then because they worked well were written down.

Back to Brahms. Does his music really not invite improvisation? We object to the notion of improvisationally (or with malice aforethought) adding, subtracting, or otherwise changing the notes of a Brahms piano piece. But I assert we still do a lot of improvising, even when we play Brahms note-for-note, true-to-the-text. All the sound colors, phrasing, rubato, nuances, voicings, etc., that change from performance to performance–the improvisational impulse is still there. And the same qualities that make for a satisfying interpretation of a Brahms piece are those that make for a satisfying realization of a figured bass or for ornamentation in the violin line of a Corelli sonata. The performer somehow captures the emotional essence of the piece and makes choices that convey that essence. (Actually, I don’t believe there is a single “essence” to a piece but this is about as close as I can get at the moment.)

What about an improvisation based on a Brahms piece? Improvising on a piece, rather than in a piece. Somehow I’m reminded of the story of a man who asks his priest, “Father, is it OK to smoke while I’m praying?” “Certainly not, my son, you should devote your whole self to prayer.” A pause. “Father, can I say a prayer when I’m smoking?” “Certainly, my son, you can pray when you are doing anything.”

Can I improvise while playing the Brahms G minor Ballade? No. Can I do an improvisation inspired on the G minor Ballade? Sure.

And can I improvise a prelude before playing a Brahms Ballade? Of course, and you’ve written about that quite extensively.

So I don’t see anything “wrong” with doing improvisations based on classical pieces (and doing it in some sort of classical, rather than jazz, style). It can be especially valuable as something to do in private as a way of exploring a piece. In public, there’s always the argument that no improvisation on a great classical work could match what the composer wrote. But that wouldn’t be the point of the improvisation.

Finally, I’m thinking of that interesting recording of the Beethoven Choral Fantasy where Robert Levin includes improvised alternatives to big opening piano cadenza Beethoven composed. That’s the sort of thing where it gets really interesting, more so in a live performance than a recording. Sure, no one can do “better” Beethoven than Beethoven. But improvising a cadenza creates a kind of drama and excitement in a performance that only comes from improvising. I know I’ve talked myself in a circle to some extent, since I suggest that there’s a lot of improvisation (or can be a lot) even in performances that stick only to the composed notes. And really great performances of classical music, to me, feel improvised.

W/r/t Brahms, one must note Jason Moran’s inspired take on the Intermezzo, Op. 118 No. 2, on the album “The Bandwagon.” You don’t even have to be a classical musician to improvise on classical music!

Thanks, Lindemann, for introducing me to Jason Moran.

Maybe one could say that the three most important things in improvisation are context, contxet, and context, at least when it comes to what is “acceptable.” I doubt anyone walked out of the Village Vanguard when Moran started improvising on Brahms. But (some) people do walk out of Gabriela Montero concerts when she starts her jazz-flavored improvisations based on classical pieces.

I recall discussing the matter of modern-day improvising with Jeffrey Kahane about 20 years ago on Compuserve’s old Music Forum (before he got too busy to take part). He learned (or taught himself) to improvise as a quite young pianist when he was playing for dance classes, and all they really needed at a given time was a set tempo and meter. So rather than choosing “real” music to play, he would take a basic idea of the right type and simply play, as the spirit moved him. He said then that he thought it was a great lack in the training of young musicians that they weren’t encouraged to do that from a quite early stage, rather than being kept focused so totally on the printed notes.

Later on he worked out prepared “original” cadenzas for Mozart concertos, but he finally decided to try improvising one himself, on the spot, as Mozart had done, and was, as I recall, pleased at being able to do that, though I don’t know whether he has continued the practice as his conducting career developed.

Of course Robert Levin is noted for that kind of improvisation, especially in Mozart, and he does so with attention to the audience of a given night. When he played a Mozart concerto with the Boston Pops on the night that his Harvard 25th reunion class as in attendance, he worked a couple of refernces to Harvard songs into the cadenza, each of which got an appreciative chuckle from the audience. That’s a very 18th or early-19th century thing to do.

The interesting thing about that passage you provided from Barbiere is that according to Garcia, his father applied rubato starting with the eighth-quarter note triplet figure at the end of the first complete measure and running through to the cadence on the last two syllables of the word “singolar.” So, in addition to ornamenting melodic lines, singers could also introduce a certain amount of elasticity in tempo, something that’s almost wholly absent today.

Some of the less experienced students in my Baroque Performance Practice class look at me in disbelief when I tell them that musicians in the Baroque were not only expected to improvise ornaments, but even an entire part (in the case of figured bass.) We have some interesting discussions about the concept of “fidelity to the composer’s intentions” in this context.

This article also calls to mind Gustav Leonhardt, who I am given to understand refuses to allow live performances of his to be recorded. He wants the freedom to take risks with the ornamentation and so on, which of course carries the risk that it can go horribly wrong. But isn’t that part of the excitement that only a live performance provides – the idea, however well sublimated, that things can go horribly wrong?

Just wanted to mention Jacques Loussier, who for MANY years has very artfully combined jazz with JS Bach.