J’ai longtemps habité sous de vastes portiques…

…dont l’unique soin était d’approfondir

Le secret douloureux qui me faisait languir.(For a long time I lived under vast porticos…

…whose only purpose was to bury, so deeply,

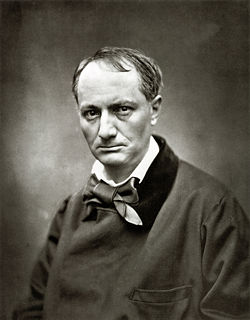

The unhappy secret that made me suffer.)— Baudelaire, “La vie antérieure”

I went to a vocal recital. Doesn’t matter where, or who sang. I’ll just say that she’s an older soprano, a star in both opera and lieder, nearing the end of her career. The setting and audience were genteel. When the singer and her pianist appeared, I thought of a scene from The Graduate, the scene at the Taft Hotel. Dustin Hoffman blunders into a party, and sees older people, who look (the women especially) as if they’d stepped out of the 1930s. Which was perfectly plausible, since those people would have grown up — would have been formed — in the ’30s. But it’s far less plausible for the singer and pianist — she in a gown, he in white tie — in 2008.

Then came the concert. It was built around groups of songs, in which composers set the same poets. Rückert, Goethe, Baudelaire. Estimable, thoughtful, serious. But let’s look at the Baudelaire group. We weren’t reading the poems, or hearing a lecture on them. We were reliving them, or at least reliving them as they were set to music by French composers. Which meant that the singer and pianist were reliving them, too, and that rather than think about them, or experience them distantly, they should have hit us right in the gut.

Did that happen? Of course not. Which isn’t to say the performance was bad. By normal standards, it was quite good, thoughtful, nuanced, expressive. But that’s not enough. Baudelaire is far more than that. He’s uneasy, troubled, sick, sensual, seduced by evil, drenched with regret. Is that what we felt, hearing those songs? Of course not. The concert was far too genteel. If the spirit of Baudelaire had emerged — if all of us wondered what secret we hid, what secret was making us suffer — the unspoken rules of the concert would have been violated. It wouldn’t have been artistic, thoughtful, genteel. It would have made us uneasy. We would have been troubled. We would have had fantasies, of nudity, jewelry, decay. Is that what we’d come for?

Did that happen? Of course not. Which isn’t to say the performance was bad. By normal standards, it was quite good, thoughtful, nuanced, expressive. But that’s not enough. Baudelaire is far more than that. He’s uneasy, troubled, sick, sensual, seduced by evil, drenched with regret. Is that what we felt, hearing those songs? Of course not. The concert was far too genteel. If the spirit of Baudelaire had emerged — if all of us wondered what secret we hid, what secret was making us suffer — the unspoken rules of the concert would have been violated. It wouldn’t have been artistic, thoughtful, genteel. It would have made us uneasy. We would have been troubled. We would have had fantasies, of nudity, jewelry, decay. Is that what we’d come for?

The form of the concert at war with its content. The form: formal, genteel; constrained and respectable. The content much less so. The difference never acknowledged.

Perhaps the performance of a Baudelaire poem that is most unsettling would be Diamanda Galas’ version of The Litanies of Satan. Even though Galas is now pretty much out of the ‘classical’ world, she got her start doing (IIRC) Xenakis and other new music. She was part of the seminal New Music America in 1982, which introduced many of us to a whole new way of listening to (and thinking about) classical music.

I think this might be one of the gems on this blog. A succinct, powerful expression of the heart of the matter: presentation and conception vs content and meaning in classical concerts.

I can’t say I’m particularly bothered by gowns-and-white-tie concert dress; it rarely distracts me. But your words about the character of the performance and the way it failed to realise the implications of the texts, really hit home.

(Elsewhere you’ve defended the HIP movement on the basis that they’ve “tapped into something”. I think that something is what you touch on in this post: they make the effort to understand the original meaning and energy of the music and then work to find ways to communicate an experience of that to a modern audience.)

Can I ask, though? Would you have allowed these artists their observation of customary concert dress if the performance of the Baudelaire set had been able to throw off the shackles of gentility and hit you in the gut?

After all, what could be more disturbing than a mature artist in a glamorous gown powerfully communicating that sick, seductive sensuality and uneasy regret? It sounds like the costume wasn’t necessarily “wrong” in this instance. (Perhaps the Emile Deroy portrait of Baudelaire is needed…)

Wouldn’t it be great then if the concert hall could create a sense of protected retreat, a place wherein the emotions could be released and where uplifting things might be found alongside disturbing things?

Alas all too rare, but during a truly fantastic performance I do feel that this is what the character of the concert hall, with its various conventions (some good, some deplorable, I’ll admit) allows me. I guess I’m saying that it’s in a concert hall (as opposed to a less formal venue) that I feel safe, as well as undistracted, to let the music uplift, disturb, do with me what it will. If the music “doesn’t” that isn’t necessarily the fault of the concert hall.

And I’m not disagreeing with you on the bigger picture – I think formality and gentility has infiltrated the concert scene in ways that are completely unhelpful and have little to do with the music itself.

Dear Greg,

I completely sympathize with your frustration with this kind of thing, and I have often found myself thinking similar thoughts after a performance, but I still have a couple of questions. First, to what extent might the composer’s music, rather than anything about the performance, have contributed to the “distancing” you experienced? Is there a chance that the contrast between gentility, restraint and nuance of the performance and the content of the poems was part of the meaning of the work? In fact, it sounds to me like the performance did move you, but not in a way that you found pleasing given your expectations regarding the Baudelaire. You were moved to think about the distance between the form, restraint, and gentility of the musical performance (Apollo?) and the less containable darkness of Baudelaire (Dionysus?). Just a thought.

Jay

I think you’ve really nailed one of classical music’s major problems in this potent little observation; too many concerts come across like feelings in aspic.

That sounds like a bad recital to me, not a good one.

Re: the culture of emotion. I recall reading some time ago now (so my memory will be patchy) of a research study into expression/release of emotion at cinema screenings. The one aspect of it that stuck with me was that there was a certain distance from strangers at which the viewers would be willing to cry in response to a movie. Once there were strangers sitting closer than that distance the subjects cried much, much less or they didn’t cry at all.

Hi Greg,

The classical audience doesn’t leave shaken very often, or questioning their lives, but neither do pop or rock audiences. That’s because most performances A) don’t aspire to or B) don’t reach that level. I can only speak for myself, but I’m often shaken by deeply moving classical concerts, whether a string quartet or an orchestra or an opera. That usually happens when the atmosphere is such that I can focus on the music without being distracted by anything else. That’s happened in jazz and rock clubs, too, when I’ve heard Donny McCaslin or Rhys Chatham. At some point, the room ceases to matter. Performers should feel comfortable to express themselves and to draw listeners to the expression in the music they believe is there. If it’s heels and a dress, then it’s heels and a dress, and I’m willing to go along with you in heels and a dress. Or jeans and a t-shirt. Just don’t wear jeans and a t-shirt if you’d rather be wearing heels and a dress, because I’ll note your fakery the moment I see you.

The URL is broken in your last response. I suppose classical concerts are set up to be soothing, and grant that many people think that about the music. But the default setting that we’ve adapted is essentially neutral, I’d argue. It can be soothing, angry, or anything in between. It’s easier to have one setting that is basically a blank slate than setting up strobe lights when the orchestra plays Varese after the Mozart symphony.

Very interesting thoughts.

I am preparing to host my own music in a premier concert. My wife and I are constantly chatting about the atmosphere of the hall in terms of the effect we want to have on the audience in relation to the music.

Having grown up in the rock era, there is a sense that the music should have some “power” to stir emotions at a very visceral level. The concert opens with a new quartet based in style on the music by bands like Yes, Kansas, Pink Floyd…. And I’d like nothing more than an audience that gets up on its feet at the end of one of the “solo” sections to cheer and applaud, even though the music continues. However, this is a classical music concert and a number of people in the audience will be fans of the Edinburgh Quartet – thinking it is highly rude to interrupt the concert with shouts and screams.

I thought about putting something in the programme to say “If the music leads you to applaud, or shout or dance, please do so.” – but this is my premier into a classical world which likes to be genteel.

Is there a solution???

In responding to Chip, you wrote, “If that doesn’t work, you might have to resign yourself to not finding a solution — and then you could try to find a way to get a more suitable audience (less genteel) for future performances!” The reverse elitism there is quite striking – the genteel as unsuitable!

But seriously (because I don’t believe you mean that as uncharitably as I’m suggesting), it’s hardly surprising that the Julliard violinist didn’t get her audience responding like she wanted. Wasn’t her request at least as odd as if Mozart had suddenly told his audience to be quiet and avoid clapping between movements? I’m not saying her request was an outright bad idea (I’ve encouraged many of my students to think creatively about audience engagement, in part inspired by some of your suggestions), but speaking as a genteel type, I would have felt horribly self-conscious trying to “put on” this new expectation – especially the “hissing.” Cultural gear-shifting isn’t that easy.

I attended that same concert and had the same reaction as you: aging lady singer in what she took to be suggestions of period costumes (she actually changed gowns at intermission!) and aging pianist in full tux. Anachronistic? That’s the problem with vocal recitals in general.

More than operas, more than symphony concerts, vocal recitals are dinosaurs. The audience at that particular concert? The singer was younger than most of the audience. I know many of them personally: they (and most recital audiences in this town) are mostly retired white folks, which is fine – I’ve nothing against retired white folks per se – but it does show that, as the decades pass, recitals of songs by long-dead composers are increasingly irrelevant to the contemporary world.

I too felt that the performance was polite, correct in its formalism – including the arch coquettishness of the singer at times; it all seemed like something out of a BBC costume series, the singer being one of those upper-class ladies of a certain age, enjoying her customary flirtations along the country-house circuit.

A regular recital-going friend in NY – a lady psychiatrist roughly the same age as the singer – attended the same program at Zankel Hall a few days later; she loved it. For all the reasons I hated it. Some soothingly familiar sounds by Mahler and Schumann and Wolf. She wasn’t so fond of the French, and positively hates anything sung in English (alas for the Coward)- because she really doesn’t want to know what the poetry MEANS.

I have often heard this from recital-goers: They want to be seduced by lovely sounds, especially familiar ones; they have no connection to the poetry, and don’t care about it; some say they don’t bother to read program notes either.

This is rather crushing to my ego (such as it is) because for the past three years I have written program notes, and done hundreds of song translations, for the Austrian Cultural Forum in NY and DC. As a young soprano, I gave up the business of singing long ago, considering it hopelessly anachronistic and rather silly; pressed into service by the Austrians, I have had plenty of time to ponder the marginal role of vocal recitals in our world today. Depressing, it is.