My first post in this series got more comments, the first day it was online, than anything I’ve ever posted here. So now I’ll give my argument in more detail. My thesis, as I’ve said, is that the classical music era — which began around 1800, when the classical music world as we know it now began to take shape — is ending.

Why do I think that? Here are my reasons, starting here, and continuing in later posts.

1. The classical music audience is disappearing. The classical music audience is now, on the average, more than 50 years old. There’s a common belief that it’s always been this old, but I’ve uncovered data that shows this isn’t true. Some of it goes all the way back to 1937, when, as part of a large-scale study of American orchestras, audience surveys were taken at the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. How old were these audiences? Much younger than the audience now. In Grand Rapids, the median age was 27. In Los Angeles it was 33. Or we can look at 1955, when the Minneapolis Symphony (now the Minnesota Orchestra) studied its audience, and — just like the Los Angeles Philharmonic two decades earlier — found a median age of 33.

In the early 1960s, a study by the Twentieth Century Fund, a major foundation, found that the median age of the performing arts audience was 38. This, the authors of the study said, was the same for all the performing arts disciplines, classical music included.

From the 1980s on, there are several sources of data. The National Endowment for the Arts has published periodic studies of the classical music audience. According to these studies, the classical music audience was (on the average) 40 years old in 1982, and 49 years old in 2002 — a steady process of aging. And at major classical music institutions, the audience seems to be older still. In Minnesota, the median age of the orchestra’s audience had gone up to 48 in 1985, and 51 in 1989. At one of America’s largest orchestras (which I can’t name, because I was given the data privately), the average age of the audience was around 50 in the late ’80s, and now is 58. And subscribers (an important part of the audience, because they’re the ones who go repeatedly, and tend to give money) are even older — their average age is 64.

So clearly the audience is aging. And — most crucially! — this isn’t a recent development. It’s been going on (if we trust the Minnesota and Twentieth Century Fund data) for more than 50 years. A trend that’s been established for that long has to reflect some kind of deep-rooted cultural change — and the change it represents, I’d guess, is that our culture, over a long span of time, has lost interest in classical music. Certainly there’s other evidence that this is so. Just look at classical music on television. In the 1950s, it was broadcast on network TV. In the ’80s, it was common on PBS; now we hardly see it at all.

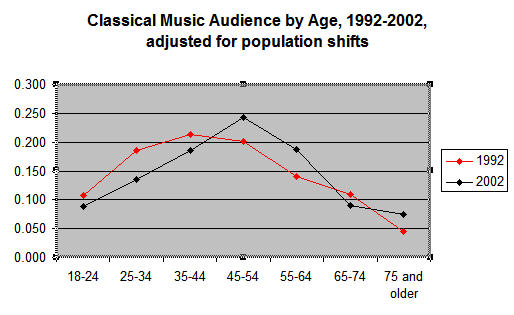

And this is where the age data starts to look devastating. If the audience has been getting older for 50 years, then clearly younger people aren’t coming into it. And in fact NEA figures show that the percentage of people under 30 in the classical music audience dropped in half between 1982 and 1997. But that’s not all — the percentage of people from 30 to 45 has been dropping, too. Here’s a chart I’ve made from NEA data, showing the age distribution of the classical music audience (the percentage of the audience in various age groups) in 2002, plotted against the age distribution 10 years earlier. (The figures are adjusted to reflect the changing distribution of these age groups in the population at large.)

What does this chart show? Look at the peaks of both curves. In 1992, the largest part of the classical music audience was 35 to 44 years old. In 2002, the largest part of the audience was 45 to 54 — which means it was the very same people who were the largest part of the audience in 1992, now grown 10 years older. This gives us a vivid picture of an aging audience, an audience whose core is growing older, and isn’t being replaced.

Will this be the last generation of classical music listeners we’ll ever see? (Or at least the last generation attracted to classical music as it’s currently performed?) I might put it this way. Some people, of all ages, will continue to join the classical music audience. But there won’t be as many of them as there used to be. Remember that the percentage of people under 30 in the audience collapsed between 1982 and 1997. If fewer of this new generation went to classical concerts when they were young, fewer will go when they’re older. Especially in our current age, when– far from turning to classical music — people over 45 now buy more pop records than younger people do, and the AARP, responding to this trend, now promotes pop music tours, as a way of attracting new members.

All of which ought to mean that the audience of the future will surely be smaller — and maybe a lot smaller — than the audience we have now. (Unless, of course, there’s some giant change in the way classical music relates to our culture.)

(I apologize for repeating things I’ve said before. But I’ve worked out this thesis in greater detail than I ever have before, and I need to get it all down in one place. For more detailed age data, including citations for some of my sources, see http://www.artsjournal.com/sandow/2006/11/important_data.html one of my previous posts.)

In future posts, I’ll give two more reasons why the classical music era looks like it’s ending:

Classical music institutions may not be able to sustain themselves (already some of them are acting as if the current funding model doesn’t work any more)

Our culture has decisively changed.

In 1900, life expectancy at birth was relatively low at 47.3 years.

The Shift to Chronic Disease Gives us Priorities

Ken McLeroy, Ph.D.

Professor of Social and Behavioral Health

School of Rural Public Health,

Texas A & M

One way of understanding the current emphasis within public health on preventing chronic disease is to examine the changes in causes of death that have occurred during the 1990s. Prior to the 1930s, the leading causes of death in the United States were infectious diseases, for example pneumonia, tuberculosis and diarrheal related diseases. The groups most affected were the very young and women of childbearing age. In 1900, life expectancy at birth was relatively low at 47.3 years.

By 1940, the U.S. had witnessed a dramatic change in causes of death from infectious disease to chronic disease with the leading causes of death becoming heart disease, cancer, stroke and injury. Largely because of the decline in mortality among infants and children, life expectancy at birth increased dramatically to 75 years in 1987 and has risen to 77.6 years today.

Hi

In your age data, you use the term “median” for the earlier examples and “average” for later ones. It’s important to note that these are not at all the same. See for example Wikipedia:Median.

Using an average/median also tells us nothing about absolute numbers attending classical music concerts, which you don’t cover, and could well be increasing.

Furthermore the growth of availability of recordings has to be a factor in deciding the size of the “classical music audience” – especially with the advent of downloadable music, I think you’ll find the absolute audience size for classical music has substantially increased over the years. Consider for example the huge numbers downloading Beethoven from the BBC.

One further important point I would raise on this subject: There is a very considerable number of people, mostly young people, who do not consider “classical” to be their first, second, or even third favourite “genre” of music. However, ask the question, “do you like classical music”, and you’d be surprised how often the answer is “yeah classical is cool man”, and you’d be surprised at the amount of basic knowledge of classical music this kind of person has. Simply look at the profiles of people on MySpace to see the evidence for this assertion. On MySpace, I regularly have people who don’t even list “classical” as a favourite adding me – a “classical” composer – as a friend, simply because (and I usually ask why) “classical’s cool, man, we like it”.

Cheers,

Tim.

Sad, but oh, so true. Why don’t the classical musicians themselves do something about it?

I would suggest a demographic caveat to your argument. Yes, the audience is aging but so is the population, especially the all-important WWII baby-boomers who represented a bulge in the populalation that keeps moving along and is now about to boost the ranks of those over 65. We were weaned on early LPs and classical music stars like Bernstein and VonKarajan. Those born after late boomers, say in the 60s and 70s didn’t benefit from the media exposure and also lacked arts education in school. But the boomers had children and we took them to museums, theatre and the arts. Not to the same degree, but you do see theseyoung adults in the audience. Check out the audience in LA with Salonen or Atlanta with Spano; maybe even St. Louis with Robertson. Ticket sales are up over 10% this year at the Metropolitan Opera because of all the fanfare. So there is hope.

I would like to clarify a comment I posted earlier today. You seem to use “median” and “average” interchangeably in your post. They have quite different meanings. Did you mean to use “average” for all of your references?

What is the breakdown of age for the entire US population today, i.e. what percentage of the population is 55+, 40-55, 30-40, etc.? I’m not going to dispute your figures, Mr. Sandow, but isn’t it also true that the entire population has shifted? We have, and will continue to have, a higher percentage of 55+ people than ever before? The good news for orchestras – and classical music, in general – is that these “senior citizens” (I’m 53!) are the best educated and wealthiest “seniors” in US history.

“our culture, over a long span of time, has lost interest in classical music”

It might be too grand a conclusion to say this based on changes in audience sizes of some orchestral concerts.

Are you speaking only of the USA? Consider Europe and see what’s going on there.

With the increase in the use of (and quality of) audio electronic equipment and media, more people listening to music at home, for various reasons.

Has the number of people enrolled in music education–public and private–gone down over the period you are considering?

You would have to look at many factors to come to the conclusion that classical music is no longer of interest.

Cost may be a factor. When the Minnesota Symphonia gives its free concerts, they are filled with younger people, sometimes whole families.

I would suggest that the classical audience has moved. They are not going to concerts at Philharmonic Hall, but listening to concerts the next day on their iPods. They get to listen to the music (whenever they want, at a reasonable price) without having to endure the rigid social scene where you can’t applaud but the eighty-year-old next to you can snore.

Your piece on the likelihood of the disappearance of classical music put me in mind of a comparable piece on the likelihood of the disappearance of movies, recently published by David Denby in the New Yorker. With one significant difference. While touching on the same interrelated factors—the combined power of money, technology, and youth culture—Denby’s piece is elegiac. Yours, like so many on the decline of classical music, at times seems to gloat, as if the end of classical music were well-deserved.

Among other reasons, because the audience is older. As if an art form that attracted a primarily older audience were worthy of contempt because its audience, for reasons of age alone, is worthy of contempt. This is not about demographics, it’s about attitude. Of course pop culture, which is to say youth culture, is the dominant culture of our time. But what if, instead of buying into that dominant culture, the discussion started with the premise that the folks in the classical audience, whatever their age, are on to something that was worth sharing?

Which includes music written 250 years ago, as well as music written last month. And which includes sitting quietly and listening to that music, another feature of classical concerts regularly thrashed as rigid, repressive, and (beyond redemption) middle-class. How about getting past the knee-jerk and considering the silence of a concert hall, like the huge black space of a movie theater, as a container for attention, for focused listening, for giving oneself up to all the experience can be? What could be more radical?

I think Denby’s got it right: “Kids who get hooked on watching movies on a portable handheld device will be settling for a lesser experience, even if they don’t yet know it—even if they never know it. And their consumer choices could affect the rest of us, just as they have in the music business. If the future of movies as an art form is at stake, we are all in this together.” Amen, brother.

Money is the problem. It’s

already been noted that

young people can’t afford

concert tickets. Worse,

schools have had to

eliminate music education

because of money constraints. In the 1930s

in elementary school in

Boston, we were taught to

sight read. Later, in

California in the 1940s,

we had Music Appreciation and heard all the well-

known classics. Where do

kids ever get a chance to

hear classical music

nowadays?

I was one of the people in the audience at your NETMCDO talk last week. Thank you *very much* — it was literally thought provoking and indeed I haven’t stopped thinking about it since.

The age distribution data are very highly suggestive of the notion that the audience are the *same* people, simply getting older … but of course the figures cannot *prove* this. Only a study specifically designed to test this theory could prove it. Maybe someone has tried doing such a survey?

It’s great that you’ve unearthed the research all the way back to 1937. There must be all sorts of problems with comparability of the data in these various surveys. However the overall trend is so huge that it presumably buries any problems caused by the disparate sources and methodologies.

Comparing and contrasting the U.S. experience with the rest of the world would be neat — a kind of “control” case to help narrow down the universal trends vs. the U.S.-specific issues. On the one hand, you have a lack of government funding for U.S. orchestras. On the other, you have an American culture of strong non-profit organizations, which (almost uniquely in a global context) makes endowment funding and “non-earned,” non-governmental funding a credible source of support for orchestras. As you point out, it is debatable whether most orchestras could rely on this non-earned income for *all* of their operating funds however. You could also argue that it would be highly undesirable for them to do so — for all sorts of reasons. But that’s another debate altogether.

You often contend that certain forms of popular music have a serious value and I agree. The way non-classical music is written has a completely different set of esthetic principles and rules that govern form and content- for instance, counterpoint and polyphony has been given up for almost exclusive homophony in most new forms of music. I think that the new forms of music that arose in the twentieth century are just that: new. Although they arose from what we consider the “Western World”, these musics cannot be analyzed and contextualized from a classical standpoint. They aren’t really related to classical music in the sense that they utilize some sort of watered down simple version of classical theory. Rock musicians certainly use the triad, but the rules of resolution and voice leading are completely different. Any mainstream (and even most niche) popular music just doesn’t conform to classical standards.

So what is my point? Well, I just think you might consider looking at how the current music in the popular realm is different from a fundamental level with classical music. The question isn’t whether people don’t value extremely well written, beautiful music- it’s that they value a different kind of music entirely. Perhaps young people do not attend for the same reason most Americans don’t attend classical Indian concerts.

I’m frankly scratching my head at the idea that [average age in the seats has risen] equals [potential audience has shrunk].

If we’re talking about the long haul, the entire _country_ has gotten older because lifespans have steadily increased. If the average audience member was 33 years old in 1937 that was a GREATER fraction of the average American’s current age than was 49 in 2002. For this reason the average audience age was sharply lower in 1937 for sports, performing arts, dog shows, and anything else we might have statistics for.

If we’re talking about music specifically, then it seems quite obvious that the characteristics of the people who currently showing up in symphony halls are today far less of a representative sample of everyone interested in the music than was true in 1967 (let alone 1937). There are far more ways to experience classical music now than was true then, and there is plenty of data showing that using those means correlates strongly with age. Older people who are interested in classical (or for that matter jazz, or bluegrass, or whatever) are obviously less likely to be comfortable with newer ways of hearing music. They are also obviously less likely to be interested in a lot of the other forms of entertainment now competing for their leisure time/money (some of which didn’t even exist in 1967 or 1937). Neither of those facts, though, bears any logical relationship to the idea that 30somethings today have less _interest_ in classical music than those of previous eras.

Isn’t it possible that the numbers of people are remaining the same, while their percentages of the increasing population are lower?

I suspect that music education has also largely reduced, thus not creating an audience – in the UK cutbacks in education have always first hit music and the arts. Now they are beginning to find music interesting again, after a fly-on-the wall documentary about a school choir which started from scratch and participated in an international competition. Choirs for all now. (That’s how TV drives government policy…)

In Eastern Europe – I live in Lithuania – the age structure is quite different. It depends very much on the programming how the ages of the audience are distributed. If the music is the old Beethoven or Tchaikovsky the audience is generally old, but throw in some contemporary music and loads of young people come to the concert. The Steve Reich concert in Vilnius was one of the most-sold-out concerts last year, and full of youngsters. Every October we have a festival of ‘ink-still-wet’ contemporary music, and it is full of young people. Similarly our festival of e-music in the spring.

It’s the young people who have more spending power to buy tickets. Having said that, when Rostropovich comes to Vilnius with outrageous ticket prices the audience consists more of the well-to-do middle-aged (who want to be seen and often know nothing about music) – these concerts are not interesting to the young ones.

I meant to add that the ticket price question is a bit of a red herring; I am sure classical concerts cost no more than football matches or pop concerts – but in those you have a real emotional experience in a crowd that you cannot have in a classical concert, unless you know your stuff. You have to sit still, cannot move, cannot talk, cannot applaud spontaneously after that brilliant cadenza….

One point I will make as a young person who likes classical music is that I know almost no one who actually wants to go to classical concerts with me, even though I typically get free tickets. (People will go to hang out with me, which is nice, but it’s a little different from actually being interested in the music.)It’s hard for me to have something that’s so important to me that I must nonetheless pursue in monkish solitude.

To draw a broader conclusion from this, I think at some point that the diminution of the younger audience from classical music halls will reach (or has reached?) a tipping point, where it’s hard to stay interested because it’s hard to make it a social activity. It’ll just be monkishly devoted people like myself. And I can tell you: We are a statistically insignificant population.

One facet of audience interest in classical music performance is the (over time) introduction and cultivation of new, worthy repertoire. As I opined in a post to Part 1 of your article, there currently is a real lack of genius composers to bring new fine pieces to the public. Of course, most audiences over the last 150 years have been resistant to new music–but within a generation the *worthy* new is embraced and becomes standard repertoire (think of Debussy, Stravinsky, Mahler, Prokofiev, etc.). Is there *any* classical music produced since 1950 which has now entered the standard repertoire of orchestra? Without new music (even if delayed in acceptance) the art form dies; and by extension the vehicle which performs it eventually dies.

There are a surprising number of pieces that get performed a lot. The Joseph Schwantner percussion concerto would be one of them. But I think the most lively work in composition goes on outside the concert hall, by people like Steve Reich.

All I ever wanted to do was to be a “classical” musician, so what you have to say, of course, worries me deeply. All the same, in my experience the situation doesn’t seem to be as dire outside of the United States. I spent 6 months in London as a student, and compared to the average BSO or NYSO attendee, I would say that the average age was far lower. In fact, I recall that whenever I went to BSO concerts my group of friends and I would feel quite markedly out of place, but I never had that experience in London. The other big difference, of course, was in ticket prices. Top LSO/LPO/Philharmonia tickets are only 30+ pounds or so; this is nothing compared to the $100+ top prices at most major American orchestras, especially when you consider it relative to the local cost of living (a rather insubstantial sandwich in London would already set you back about 3 pounds). Perhaps this is a reflection also of the average musician’s life there; from what I hear, most of them are still paid per service and have nothing like the stable contracted-with-benefits existence of many American orchestra musicians.

As you say, a complicated question with many variables, but perhaps the answer to more years of survival would also rely on those major institutions and their musicians being willing to restructure their terms in order to ensure the survival of those very institutions.

I also see not much “wrong” with the current concert format where being quiet, etc is concerned. If anything, I think it is just that modern culture does not produce many people who are willing to put in time and effort into what they consume. Items of culture should preferably be instantly digestible and immediately effective in order to reach a mass audience. I do feel that a certain amount of concentration and study is necessary to understand and love this music, which most people do not have anymore, and which most educational systems these days do nothing to instill. I’m not sure what the solution is to this, really, except to continue to lobby for better and more extensive music education.

I’m no statistician, so forgive me if this is a daft question (and I’m not disputing the validity of your stats) but how is the statistical information collected in the first place?

Three ways mentioned above to convert PowerPoint presentation to video are rather easy solutions to convert your PPT to video without any cost. You can embed your PowerPoint presentation in blog post, upload it to YouTube for sharing or transfer the video to portable video player. Alternatively you can record video while playing back your PowerPoint slideshow with screen recording software, but it’s much more complicated. If you have any idea and suggestions please let us know by leaving comments and sending email.