As I studied various Brahms scores, I was forcefully hit by something I’d thought about before, but never noticed this clearly. You can gush about great composers all you like — their magical inspiration, their matchless flights of musical creativitiy — but it’s hard to keep doing that when you study details of their orchestration, especially if you’ve ever orchestrated yourself. Yes, there are times when some orchestration idea strikes like a ray of light out of nowhere (that final chord in Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, the famous flute and trombone chords in the Berlioz Requiem, the amazing passage in the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth when the big tune gets flowingly played by low strings and contrapuntal bassoons). But often the details of orchestration take you into the composer’s workshop. You see the great names of the pantheon solving practical problems. You see them making choices — and you can see what the choices are, because the alternatives — the choices they didn’t make — are often plainly obvious.

This even applies to Mozart, often worshipped as the most magical of magical composers. But try tihinking of magic when you look at the trumpets in the first movement of the Jupiter Symphony, hammering out very basic rhythms on mostly just two notes. Inspiration isn’t striking here; instead, Mozart is making practical decisions about how to best use the trumpets to reinforce loud parts of the music. You can see him, in measures 9 through 14, choosing to use the trumpets in not quite the way he uses the horns. The horns play on all the beats; the trumpets only play on some of them. It’s easy to imagine how the music would sound if the trumpets played on all the beats, and you can see why Mozart made the choice he did.

In Brahms, you find many passages where the oboes or clarinets (or sometimes both) double the flutes an octave lower. And then you find passages where the clarinets sometimes double the flutes, and sometimes diverge from them. Again, that’s a choice Brahms is making. You can imagine the music with the clarinets literally doubling everything the flutes play. Maybe that would be too bland. THen you can imagine the music with the clarinets always playing independent parts. Maybe that would sound too thick. So you can understand Brahms’s choice, more practical than magical.

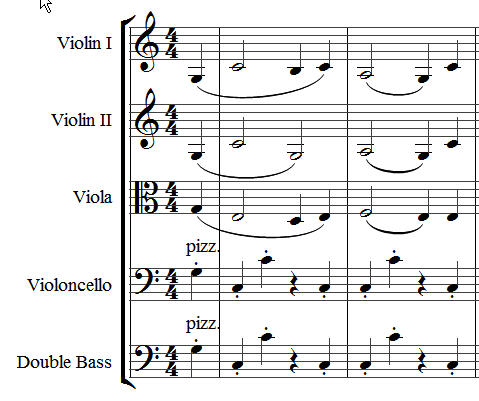

There’s a terrific example of this in the first statement of the big tune in the last movement of the first symphony. What follows, I’d better warn, is somewhat technical, so musicians (or at least people who read music) will have an easier time with it than others might. Here’s the start of the passage I’m talking about:

If you look at the strings, you see the second violins move back and forth between doubling the first violins — playing exactly what they play — and playing independent notes of their own. Why does Brahms do this? Well., at times he doesn’t have any choice. Look at the second measure i’ve quoted — the first violins are playing low A, and the violas are playing F. There isn’t any note in the chord (an F chord, the IV chord in C major) between the F and A for the second violins to play. And they can’t go down to F, since their range stops at G. So they have to play the A with the first violins.

That pretty much dooms any chance that they could have a fully independent part during the statement of this theme. But Brahms sometimes has them doubling the first violins even when they don’t have to. Look at the first measure. The first violins play C, and the violas are down on E. The chord is C major. The second violins could easily play the G between the C and the E, but instead they go up with the first violins, and double the C. Why? For two reasons, I think.

(1) If they’re sometimes going to play independent notes and sometimes double the first ivolins, they’d better switch back and forth between these roles constantly. That’s the most flowing, the most elegant way to handle them. Otherwise, their role would be rudimentary (if they doubled the first violins most of the time) or the music might sound too thick (if they played too many independent notes). (2) They start, in the previous measure, by playing low G with the first violins. And after they double the C, they go down to G to fill in a G chord while the violins play B and the violas play D. So if they played G at the point I’m talking about, their part would be rudimentary: G, G, G. By doubling the violins on the C, their part is much more flowing: G, C, G.

It’s fascinating to see these details of Brahms’s thinking. And I repeat: none of this is magical. It’s just the practical stuff a composer thinks about every day, and works out in painstaking detail. (And, if you’re Beethoven, with a lot of screaming and banging on the walls.)

One more practical Brahms decision I can’t resist mentioning. In the opening movement of the Requiem, he rather famously leaves out the violins, so the strings — now limited to violas, cellos, and basses — have a darker, more subdued tone. (He does the same thing in the second orchestral serenade.) But it’s less widely noted that he also leaves out the clarinets. Why? Because, I’d guess, he wanted a brighter woodwind sound to contrast with the darker string sound. Chords with flutes, oboes, and bassoons will have a subtle shine, even sometimes an edge, that gets muted if you add clarinets.

When I wrote out that passage from the first symphony in my notation software, I changed the C to a G in the first complete measure of the second violin part. Then I had my computer play the result. The music now sounds stiff. Brahms made the right choice.