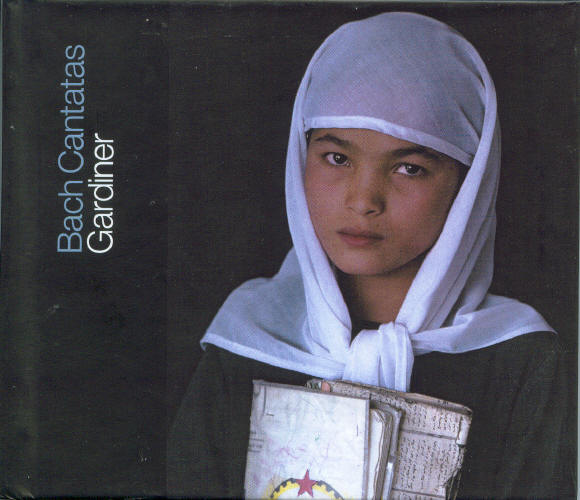

I was driving last night, and listening to Bach cantatas, from the latest instalment of the John Eliot Gardner series, the recordings he produces himself, and which have the most striking classical CD covers I’ve ever seen. For example:

The performances, I’m finding, are marvelous, devotional, but also dramatic and dance-like. They’re true to the covers, or, if you like, the covers are true to the performances. This is devotional music, the covers say, and it could speak to anybody; that’s why we show you people from many cultures in attitudes of devotion.

But that’s not what I wanted to talk about here. As I was listening, I had a sudden flash of how the cantatas might have seemed to people who heard them when they were new, in Bach’s church in Leipzig. To us, they’re classical music, with all that that implies (something special, elite, thoughtful, removed from everyday life, music to be listened to in silence). But in Bach’s time?

How would the cantatas have seemed if you, sitting in the church when they were performed, recognized the tune of every chorale? These would be the hymns you’d been singing in church your whole life. You wouldn’t only recognize them when they were sung, in a cantata, as a chorale. You’d spot them immediately when they came in over the chorus and instruments, in one of the many choruses that are chorale preludes.

You’d also recognize the dance rhythms in every cantata movement that isn’t a recitative. The music would sound like dances to you. You’d perfectly well understand that it was church music, and not to be danced to, but on the other hand you’d expect just about any music you heard to take off from some familiar dance. That’s how music in that time worked. So it could never be very distant from you.

And many other things would bring the music closer. You’d be hearing it in church. You went to church every Sunday. The church services were long, serious, and important to you. The cantata was part of that. The words would need no interpretation. They expressed your own religious views, not just because they were Christian, but because they sprung from the same Lutheran variant of Christianity that you professed.

Who wrote the music? Your own church composer, the man who played the organ at your mother’s funeral, and at your daughter’s wedding. You hadn’t exactly cheered when he was appointed; friends of yours had taken part in the process of choosing him, and from what they told you, you think you’d have preferred one of the other candidates. Bach’s music was a little too complicated for you. And when your son was in the church school, Bach yelled at him. In fact, Bach yelled at all the children, and sometimes at adults, too, which was another reason you weren’t always thrilled with him.

But then you were friends with one of the violinists who played Bach’s music at the church, and this man always told you that Bach was a wonder and a marvel. One thing you did understand, because you could hear it for yourself—he was a stunning organist. When he improvised at the beginning and the end of services, well, you’d never heard anything quite like it. And your musical ear couldn’t be all that bad, because one week you noticed that the opening chorus of the cantata Bach had written took off directly from some of the music he’d improvised the week before. So you’ll grant that the man has enormous skill. He can improvise, remember what he improvises, and use the music again next Sunday in his cantata. So even if Bach sometimes bores you, he does keep you listening. There’s no telling what he’s going to write next.

Enough…it’s wonderful, dreaming of music and life in the 18th century. I apologize for any liberties I’ve taken with musical history, or for anything in Bach’s Leipzig situation that I might have gotten wrong. But could music—and Bach’s cantatas in particular really have been received like that? I bet I’m not too far off. What listening experience today can compare?

Maybe going to hear local bands at a club, if you go constantly. You’d know the bands, you’d recognize their old songs, be curious about the new ones, and have an instant reaction, pro or con. But is anything in classical music even remotely like that now?

It’s amazing how one man can still inspire such hot debate and interpretation. I found an interesting discussion on Pandalous about how using the pedal can alone change so much to a Bach piece. It’s here: http://www.pandalous.com/nodes/bach_and_the_pedal