main: November 2009 Archives

Cindy (Schreiber) Scontriano writes from California:

I just heard your NPR interview about Vince Guaraldi. I really enjoyed it and then I had a flash from the past and wanted to ask you a few questions. I think I met Vince as a little girl. My uncle played the stand-up bass in Cal Tjader's band in the sixties and seventies. His name was Freddie Schreiber, from Seattle. I have his most famous LP, Saturday/Sunday Night at the Blackhawk. Did you happen to know uncle Freddie and if so, do you have any stories, anecdotes etc?

We lived in the bay area and sometimes my mom would take us to the Blackhawk, and other clubs, in SF to visit my uncle and hear them practice. Once the band was on TV and my uncle said "when I scratch my head, I'm saying Hi to you!" and, while he was playing the big ol' bass, he actually scratched his head on TV! I remember Vince as a warm affectionate nice man, and as a kid I listened to all the cal Tjader music, and Brubeck, and Vince I could.My uncle died young too, he had kidney failure and at that time

dialysis was reserved for people with families, etc (not single jazz

musicians with no children) and he passed in the mid seventies.Anyway, thanks for your work and if Fred Schreiber rings a bell it

would be fun to hear how.

Ms. Scontriano's message gets a reply in the form of a visit to the Rifftides archives. This item was first posted on September 13, 2005.

Freddie SchreiberFreddie Schreiber was making a mark in Cal Tjader's quintet when he died, far too young, in the 1960s. I remember him in Seattle in the mid-1950s as an aspiring bassist and an extremely witty man. He struggled to master the instrument, not with notable success. Later, within a period of two or three months, his hard work kicked in and he became a superb player. Tjader told me that he was thrilled to have Freddie on the

band. Schreiber's best recording with Tjader was Saturday Night/Sunday Night At the Blackhawk, San Francisco (Verve 8459). It has never been reissued on CD, which is a shame, but it can occasionally be found on web sites, including e-Bay. I have always liked the album. It includes, among other things, a marvelous version of Gary McFarland's "Weep," but in the July 5, 1962, Down Beat, reviewer John S. Wilson gave Saturday Night/Sunday Night a lukewarm once-over that ended with this:

Schreiber comes in for an occasional solo, but this scarcely relieves the generally monotonous sound of the group. The performances are loose and airy, but none of the soloists is sufficiently distinctive to raise the set out of an anonymous although generally pleasant rut.A few issues later, Down Beat published a response from Schreiber that has been quoted by musicians for years.

I am the bass player with Cal Tjader's group, and I have just finished reading John Wilson's review of our latest record on Verve recorded at the Blackhawk (DB, Jul 5) I think Mr Wilson was very fair in putting down Cal and the other guys in the group, but I really think he should have listened to me more carefully. Evidently he did not listen closely to my angular, probing lines, and I am sure that not once did he take note of my relentless throbbing beat. I just hope that when our next album is released, which is entitled It Ain't Necessarily Soul, that Mr Wilson pays more attention to my great playing--because, man--I'm too much!And that's one reason I miss Freddie Schreiber.

For others, see this Rifftides archive item, and this one.

And if after reading those, you haven't had enough of Freddie's genius at the art of inventing hilarious names, try this rambling discussion on the Talk Bass Forum.

In addition to the Blackhawk album, Freddie is on Tjader's Time for Two with Anita O'Day, Cal Tjader Plays, Mary Stallings Sings and his Contemporary Music of Mexico and Brazil. That to my knowledge, is the extent of the Schreiber discography. I scoured my scrapbooks and the internet for a photograph of Freddie, but could not find one. If a Rifftides reader has one and would like to share it, I'll be glad to post it.

Rifftides reader Len Gardner writes:

I recently purchased and viewed the Anita O'Day DVD in the Jazz Icons series.I am writing to you, Doug, because you wrote the fine liner notes. What I'd really like to do is write to Anita, but that is no longer possible.

What a revelation this DVD is! How marvelous her artistry is!

Too often, I buy a CD or DVD and am disappointed. Not this time. This DVD exceeded my expectations, which were already high.

For those who haven't yet seen it, be prepared to fall in love.

In the days when commercial television networks in the United States were still working their way toward the shallowness we know and love today and cable networks did not exist, there was an NBC-TV program called The Subject Is Jazz. Its host was the cultural critic Gilbert Seldes. One 1958 installment of the series explored the proposition that a fairly new tributary of the jazz mainstream ran cooler than the jazz that preceded it. The musicians were Lee Konitz, alto saxophone; Warne Marsh, tenor saxophone; Don Elliott, trumpet, mellophone and vibes; Billy Taylor, piano; Mundell Lowe, guitar; Eddie Safranski, bass; and Ed Thigpen, drums.

This investigation with examples is valuable enough that Rifftides is going to bring you the whole thing. You've had enough football this weekend anyway. It is necessary to post it in sections, which is how it is available. Here is part 1.

National Public Radio has activated a link to my interview with Scott Simon about Vince Guaraldi. This is it.

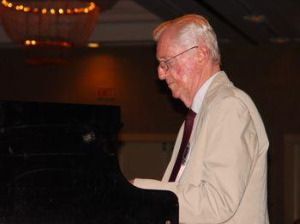

Hal Weary, A Rendezvous with Déjà Vu (halwearyjazz). Weary is a pianist from the west on the rise in New York City. The quintet numbers on his debut CD draw on the hard-bop/gospel spirit of Horace Silver and Art Blakey. On "Tenderly," he touches on but soon departs from Erroll Garner. Unaccompanied on "Praise Medley" he seems to refer to the Ellington of "Reflections in D." Weary and his sidemen, saxophonist Shantawn Kendrick, trumpet Kenyatta Beasley, bassist Gregory Williams and drummer Jerome Jennings, are newcomers to keep your ears on. In contrasting facets of his style, Beasley exhibits welcome appreciation for Kenny Dorham and Freddie Hubbard.

(halwearyjazz). Weary is a pianist from the west on the rise in New York City. The quintet numbers on his debut CD draw on the hard-bop/gospel spirit of Horace Silver and Art Blakey. On "Tenderly," he touches on but soon departs from Erroll Garner. Unaccompanied on "Praise Medley" he seems to refer to the Ellington of "Reflections in D." Weary and his sidemen, saxophonist Shantawn Kendrick, trumpet Kenyatta Beasley, bassist Gregory Williams and drummer Jerome Jennings, are newcomers to keep your ears on. In contrasting facets of his style, Beasley exhibits welcome appreciation for Kenny Dorham and Freddie Hubbard.

It would be all but impossible to keep up with guitarist Bill Frisell's trips through the myriad precincts of music he inhabits. In his discography, you'll find him in the company of Elvin Jones, ouds and bouzoukis, electronic mixes, Nashville studio aces, Jim Hall, music for silent films and string charts that might have been written by Lutoslazwski or Legiti. That's just a start.

Two recent CDs find Frisell oriented more or less toward country music. But they are not albums of country music. All Hat is Frisell's soundtrack for the motion picture of that name. It is fragmented in keeping with its job in the Texas melodrama, but Frisell connects the fragments by way of his distinctive sound and the nostalgic feeling with which he manages to inflect his every phrase.

The work of the eccentric Arkansas photographer Mike Disfarmer inspired Frisell to write and record Disfarmer. The music -- full of blues shadings -- reflects the sadness, lyricism and power that radiate out of Disfarmer's portraits of plain country people. Taken together, the CDs capture the atmosphere and emotions in parts of the contemporary rural American south. The continuity between them comes, obviously, from Frisell's playing but also from his canny employment in both projects of guitarists Greg Leisz, violinist Jenny Scheinman and bassist Viktor Krauss. Drummer Scott Amendola and harmonicist Mark Graham assist in Disfarmer.

Frisell to write and record Disfarmer. The music -- full of blues shadings -- reflects the sadness, lyricism and power that radiate out of Disfarmer's portraits of plain country people. Taken together, the CDs capture the atmosphere and emotions in parts of the contemporary rural American south. The continuity between them comes, obviously, from Frisell's playing but also from his canny employment in both projects of guitarists Greg Leisz, violinist Jenny Scheinman and bassist Viktor Krauss. Drummer Scott Amendola and harmonicist Mark Graham assist in Disfarmer.

They may seem an unlikey pair, but Frisell and the Czech pianist Emil Viklický were classmates at the Berklee School of Music in the 1970s. In 1979, they collaborated on a recording. It was just reissued as part of a CD called The Funky Way of Emil Viklický. Their five tracks with fellow ex-Berkleeites bassist Kermit Driscoll and drummer Vinnie Johnson feature an electronic keyboard and live up to the album's title with music that has something in common with what Miles Davis and Joe Zawinul were doing at the time. Or, as liner note writer Lukas Machata so elegantly describes the recording session in Prague's venerable Dejvice studio, "the quartet literally funked the hell out of the venue." On other tracks in the compilation, Viklický plays acoustic or electric piano with his big band, Karel Velebny's SHQ, the combo known as Energit and the fine singer Eva Svobodá. Regardless of context, there is a feeling of joy throughout.

Viklický's collaborations with fellow Czech George Mraz on bass have always been superb. The newest one, Sinfonietta, is no exception. Lewis Nash is the drummer except on the title track ,which has Viklický's longtime trio member Laco Tropp. The subtitle, The Janaceck of Jazz, alludes to Viklický's fondness for the great Czech composer and his ability to interpret Janacek's music and incorporate its spirit into his own compositions. Full disclosure: I wrote the notes for this album and will refrain from going on about it at length.

superb. The newest one, Sinfonietta, is no exception. Lewis Nash is the drummer except on the title track ,which has Viklický's longtime trio member Laco Tropp. The subtitle, The Janaceck of Jazz, alludes to Viklický's fondness for the great Czech composer and his ability to interpret Janacek's music and incorporate its spirit into his own compositions. Full disclosure: I wrote the notes for this album and will refrain from going on about it at length.

Tomorrow morning, November 28, I will be with Scott Simon, host of National Public Radio's Weekend Edition Saturday to discuss Vince Guaraldi. I had the privilege of writing the essay accompanying the new two-CD compilation of Guaraldi recordings. Celebrated for his Charlie Brown Christmas music, Guaraldi is the focus of a Weekend Edition feature. Mr. Simon and I will discuss the pianist's career from his early years as a sideman to his fame as the musical alter-ego of cartoonist Charles Schultz's Peanuts characters. Show producer Ned Wharton tells me that the piece is scheduled for about 9:45 a.m. Eastern Standard Time. To find your nearest NPR station, go here. Later note: You can go here to read about and listen to the conversationl.

Guaraldi recordings. Celebrated for his Charlie Brown Christmas music, Guaraldi is the focus of a Weekend Edition feature. Mr. Simon and I will discuss the pianist's career from his early years as a sideman to his fame as the musical alter-ego of cartoonist Charles Schultz's Peanuts characters. Show producer Ned Wharton tells me that the piece is scheduled for about 9:45 a.m. Eastern Standard Time. To find your nearest NPR station, go here. Later note: You can go here to read about and listen to the conversationl.

Among the friends of Eddie Locke who took part in his memorial service in Manhattan on November 22 was bassist and author Bill Crow. Locke, a stalwart drummer based in New York for more than five decades, died last September at the age of 79. Bill prepared this report for Rifftides.

At St. Peter's Church, a lot of good music was played by a lot of Eddie's friends, including Warren Vache, Richard Wyands, Jackie Williams, Murray Wall, Mike LeDonne, Paul West, Louis Hayes, Bill Easley, Lodi Carr, Tardo Hammer, Michael Weiss, Leroy Williams, Cathy Healy, Larry Ham, Jon Gordon, Bill Charlap, Sean Smith, Rossano Sportiello, Adam Nussbaum, Marty Napoleon, Ray Mosca, Ray Drummond, Barry Harris, Barry's choir of angels and your correspondent. Eddie's friend Bill Easley, his two sons, Edward Jr. and Jeffrey, and his companion, Mary Ellen Healy, gave eulogies.

Eddie was one of several remarkable Detroit jazz musicians who made careers in New York. He and Oliver Jackson developed a variety act in Detroit called "Bop and Locke," in which both drummers also sang and danced. They were booked into the Apollo Theatre in 1954, and took that opportunity to move to New York City, where Eddie met and was mentored by "Papa" Jo Jones.

Eddie began working at the Metropole, and in 1958 he joined Roy Eldridge's band. He played with Eldridge and with Coleman Hawkins through the 1960s, until Hawkins' death in 1969. During the 1970s he went into Jimmy Ryan's club on West 54th Street, and was the house drummer there until the club closed in the early 1980s.

I got to know Eddie through the cornet player Dick Sudhalter. Eddie and I were in Dick's rhythm section on many concerts and club dates. When Dick moved to the North Fork of Long Island and began playing concerts and jazz festivals there, I often picked Eddie up in Manhattan and we drove out to the jobs together. I enjoyed the stories he would tell me on those long rides, and I always enjoyed playing with him when we got there.

Eddie was also a teacher, much loved by his students. He taught music at the Trevor Day School in New York City, and also had private students. He was a great believer in the importance of passing on the lore and knowledge he had received from his elders to the next generation of jazz musicians.

The Rifftides staff thanks Mr. Crow.

For video of Eddie Locke in performance, see this earlier Rifftides posting.

Wadada Leo Smith's Golden Quartet, Spiritual-Dimensions (Cuneiform). The exploratory trumpeter follows up last year's triumphal Tabligh with a reshuffled quartet and goes himself one better by adding an excursion into electronic territory. The first CD again has Vijay Iyer at the piano and synthesizer and John Lindberg on bass, but in place of drummer Shannon Jackson Smith uses two bulwarks of avant garde percussion, Pheeroan AkLaff and Don Moye. The double drum contingent produces moments of force, as in the opening minutes of "Umar at the Dome of the Rock, parts 1 &2," but remarkable moderation later in that piece and in "Pacifica." Smith's muted long tones in "Pacifica" set a mood exploited by Lindberg and the drummers in a three-way conversation. Smith's trumpet manipulations in "South Central L.A. Kulture" set a bleak scene that soon becomes populated with aural characters suggested by the title, some vaguely menacing, some amusing in the manner of overzealous hipsters. As in his other quartet ventures, Smith employs his compositional skills in ways that leave the listener unsure what is written, what is suggested and what is pure spontaneous invention. That is as it should be when this kind of music succeeds. I don't suggest that Smith's music is easy to listen to. Nor is it intended to be. But for the listener who opens up to it, there are rewards.

Jackson Smith uses two bulwarks of avant garde percussion, Pheeroan AkLaff and Don Moye. The double drum contingent produces moments of force, as in the opening minutes of "Umar at the Dome of the Rock, parts 1 &2," but remarkable moderation later in that piece and in "Pacifica." Smith's muted long tones in "Pacifica" set a mood exploited by Lindberg and the drummers in a three-way conversation. Smith's trumpet manipulations in "South Central L.A. Kulture" set a bleak scene that soon becomes populated with aural characters suggested by the title, some vaguely menacing, some amusing in the manner of overzealous hipsters. As in his other quartet ventures, Smith employs his compositional skills in ways that leave the listener unsure what is written, what is suggested and what is pure spontaneous invention. That is as it should be when this kind of music succeeds. I don't suggest that Smith's music is easy to listen to. Nor is it intended to be. But for the listener who opens up to it, there are rewards.

CD 2 retains Lindberg and AklLaff and introduces a phalanx of electrified strings commanded by the formidable guitarist Nels Cline. It begins not with an onslaught but in a continuation of the trumpet soliloquy, full of introspection, with which Smith concluded the first "South Central L.A. Kulture" track on CD 1. Two minutes or so into the piece, three amplified guitars, Skuli Sverrisson's electric bass and Okkyung Lee's cello make themselves known underneath. (I'd have written this review just to use those musicians' names.) Now, we're getting ready for the assault. But, no. Smith continues to build the sound with the slow assurance of a practiced hypnotist, allowing each player enough individual expression to add interest without detracting from the whole. That is more or less how the rest of CD 2 unfolds, with wit, taste and restraint in the use of resources. In his later years, Miles Davis led the way to this kind of music, and he has been allotted plenty of credit and blame for it. In the final balance of Davis's music, his jazz-rock period was not his most successful, but he lifted a veil to show younger artists a new landscape. Wadada Leo Smith is one who transmogrified that vision into a personal and highly effective way of making music.

Ximo Tébar, Celebrating Erik Satie (Xàbia Jazz). Over the years, several jazz artists have interpreted individual pieces by Satie (1866-1925), the  French visionary who inspired the impressionists and whose music has outlasted the minor ones. In this invigorated collection of Satie compositions, Tébar takes his admiration nine steps further and fills a CD. An accomplished mainstream guitarist, the Spaniard's free leanings and bag of wa-wa tricks meld entertainingly with Satie's harmonic surprises and wry turns of melody. Executing precise arrangements, the octet Tébar assembled for the 2008 Xàbia Jazz Festival catches the spirit of Satie's works in the ensembles and plumbs the music's undercurrents in their solos. His band of New Yorkers are trumpeter Sean Jones, trombonist Robin Eubanks, saxophonist Stacy Dillard, keyboardists Jim Ridl and Orrin Evans, bassist Boris Koslov and drummer Donald Edwards. The Satie pieces most often trotted out - "Gymnopédie 1" and "Gnossienne 1" - are here, but so are less well-known creations like "Idylle" and "Airs A Faire Fuir," all performed with a sense of delight and discovery. Easily available in Europe, the CD has yet to pop up on US store shelves or web sites. It is worth seeking out from European sources on line.

French visionary who inspired the impressionists and whose music has outlasted the minor ones. In this invigorated collection of Satie compositions, Tébar takes his admiration nine steps further and fills a CD. An accomplished mainstream guitarist, the Spaniard's free leanings and bag of wa-wa tricks meld entertainingly with Satie's harmonic surprises and wry turns of melody. Executing precise arrangements, the octet Tébar assembled for the 2008 Xàbia Jazz Festival catches the spirit of Satie's works in the ensembles and plumbs the music's undercurrents in their solos. His band of New Yorkers are trumpeter Sean Jones, trombonist Robin Eubanks, saxophonist Stacy Dillard, keyboardists Jim Ridl and Orrin Evans, bassist Boris Koslov and drummer Donald Edwards. The Satie pieces most often trotted out - "Gymnopédie 1" and "Gnossienne 1" - are here, but so are less well-known creations like "Idylle" and "Airs A Faire Fuir," all performed with a sense of delight and discovery. Easily available in Europe, the CD has yet to pop up on US store shelves or web sites. It is worth seeking out from European sources on line.

Quartet San Francisco, QSF Plays Brubeck (ViolinJazzRecordings). The ability to swing began to steal into the ranks of classical strings players a few years ago. Although they may not discuss it in the polite company of their easily-shocked older colleagues, some of them are also improvising with proficiency and joy. There is convincing evidence of both phenomena in the QSF's CD of 10 pieces by Dave Brubeck, and Paul Desmond's "Take Five." Violinists Jeremy Cohen and Alisa Rose solo convincingly in Cohen's evocative arrangement of the Desmond tune. 5/4 time, of course, is no barrier to these conservatory-trained musicians. The violist is Keith Lawrence, the cellist Michelle Djokic, who solos dramatically on Brubeck's religious theme "Forty Days." The quartet's blend, balance and tonal qualities are those of an experienced chamber group that has developed a personality disclosed on two previous CDs. Brubeck's cellist son Matthew incorporated passages from Ellington tunes into his nimble arrangement of "The Duke." Bay Area musicians Larry Dunlap and Robert Gilmore, respectively, wrote the arrangements of "Bluette" and "Forty Days." Cohen arranged the other Brubeck pieces and an extra, "Greensleeves," under its alternate title "What Child Is This," just in time for Christmas. One of the highlights of the album is Cohen's transcription for the strings of Desmond's "Strange Meadowlark" solo from the original Brubeck quartet recording.

the polite company of their easily-shocked older colleagues, some of them are also improvising with proficiency and joy. There is convincing evidence of both phenomena in the QSF's CD of 10 pieces by Dave Brubeck, and Paul Desmond's "Take Five." Violinists Jeremy Cohen and Alisa Rose solo convincingly in Cohen's evocative arrangement of the Desmond tune. 5/4 time, of course, is no barrier to these conservatory-trained musicians. The violist is Keith Lawrence, the cellist Michelle Djokic, who solos dramatically on Brubeck's religious theme "Forty Days." The quartet's blend, balance and tonal qualities are those of an experienced chamber group that has developed a personality disclosed on two previous CDs. Brubeck's cellist son Matthew incorporated passages from Ellington tunes into his nimble arrangement of "The Duke." Bay Area musicians Larry Dunlap and Robert Gilmore, respectively, wrote the arrangements of "Bluette" and "Forty Days." Cohen arranged the other Brubeck pieces and an extra, "Greensleeves," under its alternate title "What Child Is This," just in time for Christmas. One of the highlights of the album is Cohen's transcription for the strings of Desmond's "Strange Meadowlark" solo from the original Brubeck quartet recording.

If Paul Desmond had lived, he would be 85 years old today. The last birthday he celebrated fell on Thanksgiving, 1976. For the occasion, Devra Hall cooked a turkey dinner for Desmond and her parents, Jim and Jane. She took the photograph that afternoon. Here's the story of the end of that part of the day, told by Devra in Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond.

If Paul Desmond had lived, he would be 85 years old today. The last birthday he celebrated fell on Thanksgiving, 1976. For the occasion, Devra Hall cooked a turkey dinner for Desmond and her parents, Jim and Jane. She took the photograph that afternoon. Here's the story of the end of that part of the day, told by Devra in Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond.

"It was a very quiet dinner. Paul was not feeling well, but he was clearly happy not to be home alone. He didn't have to say a word around my folks. They talked a blue streak, usually, but he was just very comfortable. My fondest recollection is that I made him dinner on his last birthday."

The senior Halls and Desmond went back to Jim and Jane's apartment when they left Devra's, and on the way stopped at the Village Vanguard. Thelonious Monk was performing there. Between sets, they all gathered in the Vanguard's kitchen, the closest thing the club has to a Green Room. In the book, Jim tells about it.

It was the most coherent conversation I ever had with Thelonious, in the kitchen with Paul and me and Thelonious. I had a sort of nodding acquaintance with Monk, but he and Paul really connected. I'm not even sure what they talked about, just standing around in that kitchen, going through old memories and things. It was nice.

It would have been intriguing if he'd sat in with Monk. I always thought I'd like to hear them play the blues together. I'll settle, gladly, for a blues with his constant companions of the l960s.

Not that Rifftides intends to become a clearing house for performance announcements, but readers do sometimes send valuable listening information. Jack Kenny writes from London:

You might want to alert your readers to this. The London Jazz Festival has just finished. I went to to the Carla concert last week and it is broadcast tomorrow. It will be online all next week on the BBC iPlayer.

Sadly for your American readers Carla seems to perform more in Europe

than she does in the States.The following is a quote from the BBC site.

Jez Nelson presents a concert given by American pianist, bandleader and

composer Carla Bley as part of the 2009 London Jazz Festival. Bringing

her long-standing quartet The Lost Chords to the Queen Elizabeth Hall,

she combines dexterous musicianship with humorous and original

compositions. The group features renowned British saxophonist Andy

Sheppard, with leading American jazz musicians Steve Swallow on bass

and Billy Drummond on drums.

Bley's prolific career has spanned four decades and many eclectic projects including Escalator over the Hill, a jazz opera that cemented her reputation as a composer. Bley also pioneered the movement towards independent artist-owned record labels by releasing and distributing her own music in the 1970s. In 2003, The Lost Chords formed out of a longstanding duo project with Steve Swallow, combining four of the major names in contemporary creative improvisation. For details of Radio 3's coverage of the London Jazz Festival go to:

The Rifftides staff thanks Mr. Kenny.

By Coincidence...

...YouTube has just posted Bley's Lost Chords in performance at Vienna's splendid Porgy & Bess club. Audio quality is acceptable. The zoom and attempts at focus during Steve Swallow's solo may induce mild seasickness but, hey, with YouTube you get what you pay for. You can always close your eyes. This was November 12.

It comes from Bill Kirchner, frequent Rifftides commenter, stalwart broadcaster and man of many parts, usually on reed instruments in the key of B-flat.

Recently, I taped my next one-hour show for the "Jazz From the Archives" series. Presented by the Institute of Jazz Studies, the series runs every Sunday on WBGO-FM (88.3).

Tenor saxophonist Jay Corre's (né Lischin) career goes back to the 1940s with the Raymond Scott and Boyd Raeburn orchestras. But his time in the spotlight came in 1966-67, when he became the most frequently featured soloist in drummer Buddy Rich's big band. Corre's warm, Lester Young/Dexter Gordon-like style served him well in a variety of moods, from ballads to burners.We'll hear Corre on several albums with the Rich band, and on a recent trio recording.

The show will air this Sunday, November 22, from 11 p.m. to midnight, Eastern Standard Time.

NOTE: If you live outside the New York City metropolitan area, WBGO also broadcasts on the Internet at www.wbgo.org.

Jazz History Preservation

Not all of the reconstruction work to be done in New Orleans is a result of Katrina's damage. One of the city's jazz landmarks has been falling apart for decades. Now, it appears that Crescent City officialdom may be about to ride to the rescue of the Halfway House. It could be a long, slow process. To read Danny Monteverde's story in The Times-Picayune and see photos of the building in its heyday and in deterioriation, go here.

l

Jazz.Com

I have not kept up with the doings at the valuable web site jazz.com now that its founder Ted Gioia has announced that he is leaving. My artsjournal.com colleague Howard Mandel, proprietor of Jazz Beyond Jazz, is looking into the matter. He has comments of his own and two lengthy responses from jazz.com contributor Alan Kurtz. To see Howard's initial piece and his exchanges with Kurtz, go here.

Eddie Locke

Family and friends of Eddie Locke will celebrate the drummer's life Sunday evening, November 22, at St. Peter's Church, Lexington Avenue and 54th Street in New York City. Widely respected as a perfomer and a teacher, Locke died on September 7 at the age of 79. In his later years, he tended to be typecast in traditional bands because he deeply felt that kind of music and had a rich history with Red Allen, Dick Wellstood, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Warren Vache, Dick Sudhalter and many other exemplars of the genre. From Teddy Wilson, Roy Eldridge and Coleman Hawkins forward, he was in demand by players in all tributaries of the modern mainstream. Locke and pianists had a particular affinity. He could be found with his fellow Detroiters Barry Harris, Tommy Flanagan and Roland Hanna, and later with Bill Charlap, Mike LeDonne and Tardo Hammer, to list a few of the thoroughly modern keyboard artists with whom he played. In this clip, he is in a familiar latterday milieu, with Duke Heitger, trumpet; Antil Sarpilla clarinet; Bill Allred, trombone; Bernd Lhotsky, piano; and Nicki Parrott, bass. This was in January, 2009, at the Arbors Records Jazz Party in Clearwater, Florida.

age of 79. In his later years, he tended to be typecast in traditional bands because he deeply felt that kind of music and had a rich history with Red Allen, Dick Wellstood, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Warren Vache, Dick Sudhalter and many other exemplars of the genre. From Teddy Wilson, Roy Eldridge and Coleman Hawkins forward, he was in demand by players in all tributaries of the modern mainstream. Locke and pianists had a particular affinity. He could be found with his fellow Detroiters Barry Harris, Tommy Flanagan and Roland Hanna, and later with Bill Charlap, Mike LeDonne and Tardo Hammer, to list a few of the thoroughly modern keyboard artists with whom he played. In this clip, he is in a familiar latterday milieu, with Duke Heitger, trumpet; Antil Sarpilla clarinet; Bill Allred, trombone; Bernd Lhotsky, piano; and Nicki Parrott, bass. This was in January, 2009, at the Arbors Records Jazz Party in Clearwater, Florida.

Among the score or so of musicians expected to perform at Locke's memorial gathering are Charlap, LeDonne, Vache, Louis Hayes, Frank Wess, Ray Drummond and Richard Wyands. Barry Harris will be music director, a.k.a. traffic cop. Previous information that John Bunch has the job was in error.

Locke's mastery of time and the fine art of wire brushes is on display in this CD with Vache, Charlap, bassist Dennis Irwin and tenor saxophonist Harry Allen.

Before the Rifftides staff gets back to business as usual, whatever that is, we're finding it difficult to let go of thoughts about Johnny Mercer. Lines from his songs won't go away -- ever.

All shuttered down...

I remember, too,

a distant bell

and stars that fell

like rain,

out of the blue.

Faint as a will-o-the-wisp,

crazy as a loon,

sad as a gypsy

serenading the moon.

The days of wine and roses

laugh and run away,

like a child at play...

Go out and try your luck--

you may be Donald Duck.

Hooray for Hollywood!

I know every trail in the Lone Star State,

'cause I ride the range in a Ford V-Eight...

This torch that I've found

must be drowned or it soon might explode.

Make it one more for my baby

and one more for the road,

that long, long road.

Alan Broadbent--pianist, composer, arranger, conductor for Diana Krall and Natalie Cole, among others--wrote in response to the Fresh Air program promoted in the previous exhibit.

Thanks for posting Dave and Rebecca's Fresh Air show which I have just finished listening to and would have missed but for you. Last week the TCM channel had a marathon of Mercer movies beginning in the late 30's and I had to sit through hours of nonsense just to see him perform. Worth its wait in gold, though.

Speaking of "P.S. I Love You": I learned it as a kid from Johnny Mathis (I think it was the flip side on a 45 of "Chances Are"). When I conduct for Diana she occasionally sings it as a solo feature and I never fail to choke up. The first time I heard her do it I could hardly conduct the next number from weeping uncontrollably. The way she sings it, It's the first time I really understood that the person writing has nothing in particular to say and that everything is said behind the words.I'm feeling very sad about the loss of it all. I was born way after my time.

But how can any of this compare to the new song my 9 year old son is learning from his guitar teacher, "Smells Like Teen Spirit"?

The Fresh Air Mercer program is archived here.

Today is the 100th anniversary of Johnny Mercer's birth. To celebrate it, Dave Frishberg and Rebecca Kilgore will be the guests on National Public Radio's Fresh Air with Terry Gross. See your local listings for station and time, or check here. If you live somewhere other than the United States or if your town doesn't have an NPR station, the network will archive the program here, usually late the day of the broadcast.

Today is the 100th anniversary of Johnny Mercer's birth. To celebrate it, Dave Frishberg and Rebecca Kilgore will be the guests on National Public Radio's Fresh Air with Terry Gross. See your local listings for station and time, or check here. If you live somewhere other than the United States or if your town doesn't have an NPR station, the network will archive the program here, usually late the day of the broadcast.

We may presume that, whatever Ms. Gross has up her sleeve, Becky and Dave will accentuate the positive, among other things. I couldn't find a clip of Mercer singing that famous song of his, but that's all right because we can enjoy him with Bing Crosby in a recently unearthed television performance. It's not jazz, except in the sense that these guys were marinated in jazz from the 1920s on. But, hey, Mercer mentions Bix.

Kurt Rosenwinkel, Reflections (Wommusic). From his first recordings in the 1990s, Rosenwinkel's guitar playing has had an element of pensiveness. Regardless of tempo, complexity or adrenalin-fueled collaborators, he radiates the air of a man who won't hurry through even his most complex improvisations. Rosenwinkel's assurance and thoughtfulness are consistent in this set of standards, jazz classics and one original. Bassist Eric Revis and drummer Eric Harland are capable of speed and intensity, but here they are at one with Rosenwinkel's thoughtfulness. The trio gives particularly loving treatment to Thelonious Monk's title tune, Wayne Shorter's "Ana Maria" and the standard ballad "More Than You Know." The album's longest track begins with Rosenwinkel's leisurely unaccompanied introduction to his "East Coast Love Affair," a tune beginning to show staying power in the jazz repertoire.

the air of a man who won't hurry through even his most complex improvisations. Rosenwinkel's assurance and thoughtfulness are consistent in this set of standards, jazz classics and one original. Bassist Eric Revis and drummer Eric Harland are capable of speed and intensity, but here they are at one with Rosenwinkel's thoughtfulness. The trio gives particularly loving treatment to Thelonious Monk's title tune, Wayne Shorter's "Ana Maria" and the standard ballad "More Than You Know." The album's longest track begins with Rosenwinkel's leisurely unaccompanied introduction to his "East Coast Love Affair," a tune beginning to show staying power in the jazz repertoire.

Every once in a while another 100 Best Jazz Recordings list pops up. A new one is batting about the ethernet. This time the source is the UK newspaper the Telegraph. The compiler is Martin Gayford, an art critic, biographer and sometime jazz critic. It's a good list, but anyone who has the temerity to choose the best of anything, even the hundred best, opens himself up to the ire of fans. Mr. Gayford's list, published on November 10, has already attracted a batch of "how could you leave out ___________" complaints. Please direct yours to the Telegraph and Mr. Gayford, not to Rifftides. To see the list, go here.

Every once in a while another 100 Best Jazz Recordings list pops up. A new one is batting about the ethernet. This time the source is the UK newspaper the Telegraph. The compiler is Martin Gayford, an art critic, biographer and sometime jazz critic. It's a good list, but anyone who has the temerity to choose the best of anything, even the hundred best, opens himself up to the ire of fans. Mr. Gayford's list, published on November 10, has already attracted a batch of "how could you leave out ___________" complaints. Please direct yours to the Telegraph and Mr. Gayford, not to Rifftides. To see the list, go here.

How could he leave out Woody Herman?

Dick Katz, The Line Forms Here (Reservoir). The news of Katz's death at 85 last week sent me to the  shelf for this 1996 recording. It covers the range of his talents as pianist, composer and arranger. He plays alone in a moving performance of Duke Ellington's "Lotus Blossom," in a trio supported by bassist Steve LaSpina and drummer Ben Riley, and blends the tenor saxophone of the veteran Benny Golson and the trumpet of newcomer Ryan Kisor in quintet arrangements. In the CD's three blues pieces, notably on John Coltrane's "Mr. P.C.," Katz discloses himself as one of the most canny modern jazz blues players.

shelf for this 1996 recording. It covers the range of his talents as pianist, composer and arranger. He plays alone in a moving performance of Duke Ellington's "Lotus Blossom," in a trio supported by bassist Steve LaSpina and drummer Ben Riley, and blends the tenor saxophone of the veteran Benny Golson and the trumpet of newcomer Ryan Kisor in quintet arrangements. In the CD's three blues pieces, notably on John Coltrane's "Mr. P.C.," Katz discloses himself as one of the most canny modern jazz blues players.

Admired for his harmonic knowledge and the subtlety of his touch, Katz was a favorite of the Modern Jazz Quartet's pianist and music director John Lewis, who arranged for his first recording contract. In his days as one of New York's busiest utility players, Katz worked with with Tony Scott, Roy Eldridge, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Kenny Dorham, and Carmen McRae, among many others. He came to the attention of a wide audience with the success of Benny Carter's Further Definitions, on which he was the pianist in Carter's spectacularly successful mixed marriage of swing and bop musicians. His collaborations with singer Helen Merrill, on the Milestone recordings The Feeling is Mutual and A Shade of Difference, fell out of print as vinyl albums, but Mosaic Records rescued them in a CD reissue. With Orrin Keepnews, Katz founded the short-lived but productive Milestone label.

worked with with Tony Scott, Roy Eldridge, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Kenny Dorham, and Carmen McRae, among many others. He came to the attention of a wide audience with the success of Benny Carter's Further Definitions, on which he was the pianist in Carter's spectacularly successful mixed marriage of swing and bop musicians. His collaborations with singer Helen Merrill, on the Milestone recordings The Feeling is Mutual and A Shade of Difference, fell out of print as vinyl albums, but Mosaic Records rescued them in a CD reissue. With Orrin Keepnews, Katz founded the short-lived but productive Milestone label.

For a comprehensive obitutary of Dick Katz, see Ben Ratliff's New York Times article. For further insights through an interview with Katz, go to this installment of Marc Myers' JazzWax. On its web site, WNYC-FM in New York has a video made last May of Katz reminiscing and playing with his contemporaries vibraharpist Teddy Charles, bassist Bill Crow and drummer Ron Free. The Rifftides staff thanks WNYC for permission to show it to you.

John Hollenbeck Large Ensemble, Eternal Interlude (Sunnyside). The ensemble is Large, all right, in the size of the band -- 20 pieces -- and in the expansiveness of Hollenbeck's vision. He is a composer  who moves into, out of and beyond established categories of musical thinking and a drummer who brilliantly meets the challenges he sets himself in his writing. Drawing on his mentor Bob Brookmeyer's example of originality and fearless innovation, Hollenbeck tempers the contemporaneity of his ideas with glances into the rear-view mirror of his creative imagination. Hence, his amusing expansion of the main idea of Thelonious Monk's "Four In One" into "Foreign One." Gary Versace's neo-boogie piano introduction sets up an expanding and contracting field of rhythmic patterns, orchestral textures and solos. It ends in a fiesta of intersecting lines across the brass and reeds, melding into 18 concluding quarter notes struck in unison on piano and cymbals, as insistent as a railroad crossing's warning signal.

who moves into, out of and beyond established categories of musical thinking and a drummer who brilliantly meets the challenges he sets himself in his writing. Drawing on his mentor Bob Brookmeyer's example of originality and fearless innovation, Hollenbeck tempers the contemporaneity of his ideas with glances into the rear-view mirror of his creative imagination. Hence, his amusing expansion of the main idea of Thelonious Monk's "Four In One" into "Foreign One." Gary Versace's neo-boogie piano introduction sets up an expanding and contracting field of rhythmic patterns, orchestral textures and solos. It ends in a fiesta of intersecting lines across the brass and reeds, melding into 18 concluding quarter notes struck in unison on piano and cymbals, as insistent as a railroad crossing's warning signal.

"Eternal Interlude," the title piece, is nearly 20 minutes of impressionism in which the sensation of floating is sustained through energy created by the contrast between long ensemble tones centered on flutes, and percussive effects of marimba, piano and drums. In this piece, the exquisite subtlety in Hollenbeck's writing is reminiscent of what the late Gary McFarland used to achieve with woodwinds. Much the same can be said of "The Cloud," which has the added elements of whistlers, a section of aphorisms spoken by Theo Bleckmann and Bleckmann's wordless vocalizing. "Perseverance" comes as close to traditional big band writing as we're likely to hear from Hollenbeck. The resemblance is mostly in contrapuntal lines between brass and reeds, a succession of rowsing, even rowdy, saxophone solos and a masterly drum solo.

comes as close to traditional big band writing as we're likely to hear from Hollenbeck. The resemblance is mostly in contrapuntal lines between brass and reeds, a succession of rowsing, even rowdy, saxophone solos and a masterly drum solo.

In "Guarana," infectious Latin rhythms and minimalist repetition work hand in hand. "No Boat" is a two-minute tone poem, full-bodied but subdued. It has the effect of a closing prayer.

Yesterday was the Marine Corps' 234th birthday. Today is Veterans Day and Ernestine

Anderson's birthday. To celebrate all three, I gave the Rifftides staff the day off and my Italian friend Vigorelli Bianchi took me on a long, looping tour of this big old valley.

Back to work tomorrow. The plan is to do a bit of catching up, with brief reviews of additional recent, and maybe a few not-so-recent releases.

Linda Oh, Entry (Linda Oh Music). Oh is a 25-year-old Chinese from Malaysia who grew up in Australia, plays bass and has a Masters degree from the Manhattan School of Music. Her music, as eclectic as she, eludes classification except as fresh and uncompromising. She achieves remarkable unity using spare instrumentation, nicely crafted compositions and sidemen who listen closely and react to her, as she does to them. Trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and drummer Obed Calvaire share Oh's instrumental skill and her economical application of it. Her acoustic bass sound is firm, clear and deep. She has no evident tendency toward invading guitar territory, as many young bassists do, and she makes satisfying note choices even in material that might encourage the randomness of free jazz.

Linda Oh, Entry (Linda Oh Music). Oh is a 25-year-old Chinese from Malaysia who grew up in Australia, plays bass and has a Masters degree from the Manhattan School of Music. Her music, as eclectic as she, eludes classification except as fresh and uncompromising. She achieves remarkable unity using spare instrumentation, nicely crafted compositions and sidemen who listen closely and react to her, as she does to them. Trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and drummer Obed Calvaire share Oh's instrumental skill and her economical application of it. Her acoustic bass sound is firm, clear and deep. She has no evident tendency toward invading guitar territory, as many young bassists do, and she makes satisfying note choices even in material that might encourage the randomness of free jazz.

The music has moments of annunciatory boldness--there is a kind of bebop fanfare in "Gunners"--but even at its most complex and active, Oh, Akinmusire and Calvaire exercise the restraint of artistic judgment. In "Numero Uno," Akinmusire overdubs himself into a brass choir of contrapuntal voices before the piece evolves into a series of thoughtful solos and a stretch of interactive improvisation. The swift "Fourth Limb" is all three-way interaction for its first half, with sparkling trumpet work from Akinmusire over Calvaire's pointillist drumming, then a bass solo that manages coherence at a demanding tempo. Though the CD package gives no composer credits, all of the pieces but one seem to be by Oh. The album concludes with the contrast of intensity and, ultimately, peacefulness in a cover of The Red Hot Chili Peppers' "Soul to Squeeze." This is the debut recording of a musician who leaves the listener with a keen sense that she knows who she is and where she is headed. It is available as a CD here or an MP3 download here.

Because of the high volume of comments Rifftides received following our piece on the death of pianist Eddie Higgins, the staff thought there might be widespread interest in a memorial concert. We bring you the announcement as it arrived by e-mail from Florida. This will give you time to make plans to fly in from, say, Tokyo or St. Thomas.

There will be a Jam Session tribute to Eddie Higgins on Sunday, December 6 from 4pm to 6pm in the ArtServe auditorium at 1350 E. Sunrise Blvd.(Ft. Lauderdale Library branch)

Haydn (Eddie) Higgins 1932 to 2009

Pot Luck finger food, please. Soft drinks provided. BYOB.Free admission.

Contributions to the Haydn (Eddie) Higgins Memorial Music Scholarship Fund

will be gratefully appreciated.

For information about the jam session and scholarship, call 954-524-0805.

I think Haydn would like the BYOB part.

Family members and friends are planning a memorial service for Stacy Rowles. No date has been set. The trumpeter and singer died at home in Burbank, California, on October 27 of injuries from an automobile accident two weeks earlier. She was 54. The daughter of pianist Jimmy Rowles, she studied piano for a time. Despite her father's example, she was not attracted to the instrument. She eventually tried an old trumpet that was in the Rowles house and immediately took to it. The vibraphonist and teacher Charlie Shoemake, with whom she studied for a time, told me today, "Stacy was a natural talent. She listened to the right people, and her ear took her to the right places."

Ms. Rowles and her father co-led a group in Los Angeles for a time in the early 1990s. She recorded three albums with him. They included Me And The Moon, which featured her on flugelhorn and as a singer. Jimmy Rowles died in 1996. Me And The Moon is an out-of-print collector's item. Jazz enthusiast and frequent Rifftides correspondent Gordon Sapsed used the title tune as the soundtrack for a tribute montage of his photos of Stacy. He posted it on YouTube. Both Rowleses play and sing.

She recorded three albums with him. They included Me And The Moon, which featured her on flugelhorn and as a singer. Jimmy Rowles died in 1996. Me And The Moon is an out-of-print collector's item. Jazz enthusiast and frequent Rifftides correspondent Gordon Sapsed used the title tune as the soundtrack for a tribute montage of his photos of Stacy. He posted it on YouTube. Both Rowleses play and sing.

Also on YouTube, but off-limits to embedding bloggers, are two performances by Swinging Ladies, one of several all-female groups with which Stacy Rowles played. They are from a concert in front of Hannover, Germany's, imposing town hall, the Rathaus, in 1998. With her are Sharon Hirata; alto and tenor saxophone; Janice Friedmann, piano; Lindy Huppertsberg, bass; and Jill Fredericksen, drums. You will find them by clicking here and here.

Bill Crow's column, The Band Room, has for decades been a feature of Allegro, the monthly publication of New York's Local 802 of the American Federation of Musicians. He fills it with what he is most famous for after his bass playing, anecdotes about musicians. Sometimes the stories concern well-known performers, sometimes less celebrated journeymen. It took me a couple of minutes to recover from the one that follows.

Federation of Musicians. He fills it with what he is most famous for after his bass playing, anecdotes about musicians. Sometimes the stories concern well-known performers, sometimes less celebrated journeymen. It took me a couple of minutes to recover from the one that follows.

Richard Chamberlain tells me that, at a New York City Ballet rehearsal some years ago, Lester Cantor, who frequently subbed there in the bassoon section, was playing baritone sax on a set of Charles Ives pieces. The conductor, Hugo Fiorato, stopped at one point and said, "Bari sax... too much!" Lester immediately replied, "Thanks, man!" Richard says the orchestra was unable to play for several minutes. It wasn't until intermission that Fiorato figured out what was so funny, when one of the hipper violinists explained the joke to him.

To read all of Bill's November column, go here. You can find his books of jazz anecdotes here and here.

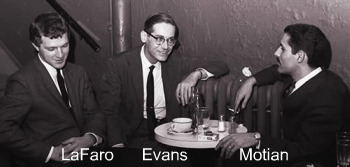

The Rifftides series of posts on improving hearing by listening to bass lines leads inevitably to Scott LaFaro. It was less LaFaro's virtuosity that made a difference in the role of the bass than the uncanny group thinking and interaction he made possible in the Bill Evans Trio. LaFaro was what Evans had been looking for, dreaming of, a bassist who thought about music, and specifically about time, as the pianist did. There is an invaluable pre-LaFaro Evans album with his friend Don Elliott, the multi-instrumentalist. The CD consists of informal rehearsals at Elliott's house in 1956 and '57. I reviewed it for JazzTimes eight years ago. Here is the applicable section of the review.

In a snippet of conversation at the end of their workout on the changes of "Doxy" (misidentified in the booklet as "Blues #2"), Evans talks about his ideal of group interaction.

Evans: "I like to blow free like that, with no 'four' going, but you know where you're at. It's crazy. If everybody could do that, if the bass could be playing that way --why not-- drums could just..." (he vocalizes in imitation of a drummer playing free).Elliott: "That's right; doesn't have to help you."

Evans: "Not if everybody feels it, man."

It would be 1959 before Evans put bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian together in a group in which everybody felt his way of playing time. They went on to reform the very idea of the jazz trio, but this glimpse into his thinking tells us that Evans was ready years earlier.

LaFaro may have felt ready when Evans was expressing his vision to Elliott, but he was on the west coast, a 21-year-old still developing. There is precious little of him on record from his Los Angeles days. Two recordings, one with Victor Feldman, the other with Cal Tjader and Stan Getz, provide strong indications of his growing musicality and technical prowess.

There is even less of early LaFaro on film or tape, to my knowledge only two pieces, both from Bobby Troup's Stars of Jazz television program. LaFaro was in tenor saxophonist Richie Kamuca's formidable quintet with Feldman on piano, trombonist Frank Rosolino and drummer Stan Levey. Here are both of those clips, "Cherry" and "Chart of my Heart." The video quality is dreadful and there are audio dropouts, but this is our only option for seeing Scott LaFaro in action. If your speakers have tone controls, turn up the bass setting and you'll find it easier to follow his lines.

There is no video of the Evans trio with LaFaro and Motian. Their primary recorded legacy is in Portrait in Jazz, Explorations and Sunday at the Village Vanguard. The CD titled Waltz for Debby was compiled from the Vanguard date. This is its title tune, decorated with a photo montage courtesy of whoever posted it on YouTube.

That was June 25, 1961. Twelve days later, Scott LaFaro died at the wheel of his automobile when it crashed in upstate New York. He was 25 years old.

It would be inaccurate, but not grossly inaccurate, to say that no jazz bassist who emerged from the 1960s onward developed free of debt to LaFaro. To the extent that Evans, LaFaro and Motian changed the concept of the piano trio--and that is a considerable extent--LaFaro's influence extends much further than the bass.

It would be inaccurate, but not grossly inaccurate, to say that no jazz bassist who emerged from the 1960s onward developed free of debt to LaFaro. To the extent that Evans, LaFaro and Motian changed the concept of the piano trio--and that is a considerable extent--LaFaro's influence extends much further than the bass.

In the first paragraph of Part 3 of this series, it was not by random choice that I included Red Mitchell's name in the short list of important bassists who emerged in the 1940s. He discovered ways of playing the instrument that made a difference in the bass's role in jazz. Bill Crow, the hero of part 3, has kindly agreed to expand on some of the reasons for Mitchell's importance.

In between the Blanton (and Pettiford) soloing styles that were so influential in the 1940s and 50s and the new age that was marked by Scott LaFaro's playing, was Red Mitchell. Red was the first bassist I heard who used a lower action, pressed rather than pulled the strings and used some left-handed plucking articulation. It cut his in-person volume down a lot, but was phenomenal on recordings. And his solo lines were melodic, horn-like, and very original. He opened up the ears of a lot of us to other possibilities of the instrument. I think he may have given Scotty some ideas. And this was all pre-amplification. When Red finally started using pickups, the result was beautifully audible soloing at the highest level.

Bill Crow

In the early 1980s, Mitchell worked frequently in a duo with Bill Mays. In their performance of a Thelonious Monk piece, he demonstrates what Bill Crow emphasizes about his peer's skill and originality.

For the new segment of our adventure in letting bassists be our guides, author, critic and sometime Rifftides commentator Larry Kart has a fine idea.

May I suggest, for Part 4, Paul Chambers behind Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly and Jimmy Cobb on "So What." Like Heath and LaFaro in their various ways, where Chambers puts "one" is a place where no one who's playing with him literally is, but it's a place that all can touch and play off of. I think that's a fairly basic (no play on words intended) general principle.

Good suggestion. The performance is from a 1959 episode of The Robert Herridge Theater on CBS-TV. Herridge introduces the program and the piece. Gil Evans leads the orchestra, whose function in this clip is to set the mood for "So What."

As you may recall from parts 1 and 2, our theme in this series is that by concentrating on the lines played by a good string bassist, you can gain an understanding of the shape and structure of a piece of music, feel its heartbeat, sense its soul. Duke Ellington's Jimmy Blanton in the early 1940s opened the possibilities of the bass as an improvising instrument in modern jazz. Oscar Pettiford followed, then Ray Brown, Charles Mingus, Red Mitchell (this is a limited and selective list) and Scott LaFaro.

From the early 1960s, in great part due to LaFaro's influence, bassists went beyond the instrument's traditional basic function in jazz of supplying swing and harmonic guidance. In many cases for better, in others for worse, virtuosity to the point of acrobatics became a part of standard bass operating procedure.

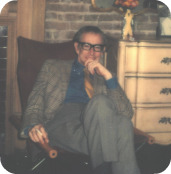

A consistently satisfying bassist from the pre-gymnastics era of the instrument, still at work, is Bill Crow. A trumpeter, then a drummer, then a valve trombonist, Crow became a bassist in 1950. A very few of the leaders he has worked with are Stan Getz, Claude Thornhill, Terry Gibbs, Clark Terry, Bob Brookmeyer, Al Cohn, Lee Konitz, Marian McPartland and Eddie Condon. I'm showing you a picture of Bill because in the clip that follows, you will get only a glimpse of him behind the front line of the Gerry Mulligan Sextet.

A consistently satisfying bassist from the pre-gymnastics era of the instrument, still at work, is Bill Crow. A trumpeter, then a drummer, then a valve trombonist, Crow became a bassist in 1950. A very few of the leaders he has worked with are Stan Getz, Claude Thornhill, Terry Gibbs, Clark Terry, Bob Brookmeyer, Al Cohn, Lee Konitz, Marian McPartland and Eddie Condon. I'm showing you a picture of Bill because in the clip that follows, you will get only a glimpse of him behind the front line of the Gerry Mulligan Sextet.

This was Rome in 1956, the same year the picture was taken. The other players are Mulligan, baritone saxophone; Bob Brookmeyer, valve trombone; Zoot Sims, tenor saxophone; Jon Eardley, trumpet; and Dave Bailey drums. The piece is Mulligan's "Walkin' Shoes." The absence of a piano means that the bass is crucial to the harmonic life of the tune. The listener can let it be his guide without a redundancy of chords from a piano. You may notice that the members of the big band in the background are paying rapt attention. No wonder.

Let us pursue the music appreciation method outlined in Part 1 (see the following exhibit). The theory is that concentrating on the bass lines of superior players can sharpen your perception of the music. Today's lesson is from another great bassist. It's Niels Henning Ørsted-Pedersen in 1971 at the Café Monmartre in Copenhagen. Niels Jørgen Steen is the pianist, Jørn Elniff the drummer, Finn Ziegler the violinist.

NHØP was 25 years old. He had already established himself as the bassist most in demand by American musicians visiting Europe. Concentrate on his notes and you will be rewarded. Shortly after the video begins, Ben Webster and Charlie Shavers, the co-leaders of the band, discuss the premise.

In the days when I was learning to truly listen, Red Kelly gave me a piece of valuable  advice. He told me to close my eyes and in my mind isolate and concentrate on the bass player. He said that when I felt and understood what the bassist was doing, the rest of the music would begin to fall into place. It was a coincidence, of course, that Red was a bass player.

advice. He told me to close my eyes and in my mind isolate and concentrate on the bass player. He said that when I felt and understood what the bassist was doing, the rest of the music would begin to fall into place. It was a coincidence, of course, that Red was a bass player.

As an impoverished student, I had a limited record collection. It consisted of a dozen or so 10-inch LPs, and it happened that Percy Heath was the bassist on about half of them, with Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk and the Modern Jazz Quartet, then a new group.

so 10-inch LPs, and it happened that Percy Heath was the bassist on about half of them, with Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk and the Modern Jazz Quartet, then a new group.

Red's advice was invaluable. To this day, I lock in on the bassist for a blueprint to the shape of a piece, and I am still fascinated by Heath's bass lines. In the following performance by the MJQ of Milt Jackson's blues "Bag's Groove," Percy is in customary form with his spacious but concentrated tone, impeccable note choices and irresistible swing. This is from the Zelt festival in Freiburg, Germany, in 1987. The video producers insert a title misnaming the tune. A German YouTube viewer reacts in the comment section:

"das insert "BACKGROOVE" ist richtig peinlich!"

"Really embarrassing," he says. Well, yes, but not as embarrassing as the director, asleep at the switch, who keeps the camera on John Lewis during all three choruses of Heath's bass solo. Nonetheless, this is a splendid performance. You may as well close your eyes and focus your attention on Percy's notes because you're going to see little of him.

Red Kelly is the bassist on Kenton At The Tropicana, one of the best live albums in Stan Kenton's discography. Backed by the Kenton trombones, Red also appears as featured vocalist on the heartbreaking ballad "You and I and George." In a small group setting on another album, he is with his friend and fellow bassist Red Mitchell and guitarist Jim Hall in the classic Good Friday Blues, now packaged with other Hall recordings in a CD called Blues On The Rocks. Mitchell plays piano and leaves the bass work to Kelly.

The television comic Soupy Sales loved jazz, knew its history and many of its leading players. Early in his career, when he had a local show in Detroit, he frequently presented jazz stars as guests. After Sales died on October 22 at the age of 83, many obituaries mentioned that the only known video of Clifford Brown performing is from a kinescope recording of the Sales show. For decades, it was assumed lost, but Sales found the film in his garage in the mid-1990s. Here is the trumpeter in February, 1956, five months before he died at 26 in an auto crash, playing "Lady Be Good" and "Memories of You."

Study in Brown, mentioned by Clifford in the interview, is one of the important albums by the quintet he led with drummer Max Roach. The Dinah Washington jam session with Brown, Roach, Maynard Ferguson, Clark Terry and Herb Geller--among others--is another basic repertoire item for serious jazz listeners.

Happy November.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary