main: May 2009 Archives

Thirty-two years ago today, Paul Desmond bid his girl friend goodbye as she set off for London, urging her to have a good holiday. That was on Friday. He would be fine, he told her; he had friends coming the next day. But his only companion that weekend was the lung cancer that had ravaged him during the past year. His housekeeper found him dead on Monday, Memorial Day.

Marian McPartland said, "It's just like Paul to slip quietly away when everyone's out of town, not to bother anybody." Dave Brubeck still says, "Boy, do I miss Paul Desmond." Details of Paul's passing--and his life--are in Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond.

Here he is at the 1975 Monterey Jazz Festival two years before his death.

Bill Mays and Red Mitchell constituted one of the great piano-bass duos of the 1980s. Musicians and dedicated listeners still talk about their gigs at Bradley's in New York's Greenwich Village. Their album Two of a Mind has been out of print for years, although it shows up from time to time on web sites including this one, at prices ranging from high to heart-stopping. In 1982, Mays and Mitchell made two programs that ran on KCET, the Los Angeles public television station. Four pieces from those programs have just materialized on YouTube. Here are two of them, both written by Thelonious Monk.

How did Mitchell get that sound, clear and precise, yet the size of Grand Central Station? His tone was always big, but after 1966 when he changed his bass tuning from fourths to fifths (as violin, viola and cello are tuned), it became enormous. He explained it to Gene Lees:

If you tune an instrument in fourths, you get a scale that is shorter physically. The top notes are lower, the bottom notes are higher in pitch. If you tune an instrument in fifths, you get a bigger scale. The top notes are higher, the low notes are lower.

There's more to it than that; the tuning in fifths also effects how the notes sustain, or ring. For detail, read the entire interview with Mitchell in Lees' indispensable book Cats of Any Color. It is fascinating for the fluidity, profundity and coherence of Mitchell's ideas about music and life.

Mitchell died in 1992. Mays is thriving.

Red played the most gorgeous melodic solos of anybody on any instrument. I think maybe he and Lester Young were in the same league. The fact that it was coming out of a string bass was mind-boggling. -- Jim Hall

Simple isn't easy. -- Red Mitchell

There is little question that the 1940-41 edition of the Duke Ellington orchestra, the so-called Blanton-Webster band, was Ellington's finest. Legions of Ellington lovers have listened to it so often that they can sing along with its arrangements and the solos by Webster, Ray Nance, Johnny Hodges, Ellington and the other members.

Still, I've always had a soft spot for the band Ellington took on the worldwide road in the 1960s until shortly before he died in 1974. The musicianship was extraordinary, of course, and there was something endearing about its laid-back collective attitude. A video displaying both aspects has shown up on Google. Paul Gonsalves, Harry Carney, Cootie Williams, Booty Wood and Russell Procope are among the sidemen. The film runs about 40 minutes, so you might want to save it for when you have time to settle in and enjoy it. This is Ellington in La Bussola, Focette (near Viareggio), Italy, in July, 1970, four months after the release of the recording of his New Orleans Suite.

Blogging must sometimes take a back seat to gainful employment. I'm roundin' third and headin' home* in one deadline project, an essay and play-by-play account of the music for the Anita O'Day entry in the next Jazz Icons series**. It has been an adventure in research into the two European concerts on the DVD. As soon as that wraps up, I'll begin notes for Bud Shank's final CD, then a piece about Emil Viklický's forthcoming trio CD with George Mraz and Lewis Nash. I may even get in a little work on my alleged next novel. While all that's going on, I hope to bring you a few items of interest. Thanks for your patience.

Blogging must sometimes take a back seat to gainful employment. I'm roundin' third and headin' home* in one deadline project, an essay and play-by-play account of the music for the Anita O'Day entry in the next Jazz Icons series**. It has been an adventure in research into the two European concerts on the DVD. As soon as that wraps up, I'll begin notes for Bud Shank's final CD, then a piece about Emil Viklický's forthcoming trio CD with George Mraz and Lewis Nash. I may even get in a little work on my alleged next novel. While all that's going on, I hope to bring you a few items of interest. Thanks for your patience.

*For puzzled readers not in the US, that is a quaint allusion to baseball.

**Here are the titles, coming out in October:

Coleman Hawkins- Live in '64- (w/ Sweets Edison)

Art Blakey- Live in '65- (w/ Freddie Hubbard)

Max Roach - Live in '68

Jimmy Smith- Live in '65 & '69

Woody Herman- Live in '64

Anita O'Day- Live In '63 & '70

Art Farmer- Live In '64- (w/ Jim Hall)

Boxed Set featuring bonus performances, including a one-hour unseen Coleman Hawkins concert from the Adolphe Sax Festival in Belgium in 1962.

Sometime in the final decade of the last century (man, that's beginning to sound like a long time ago) I was on assignment in Portland, Oregon, and dropped into the restaurant of the elegant Heathman Hotel to hear pianist Dave Frishberg and singer Rebecca Kilgore. A cornetist was sitting in with them that night. On the spot, Jim Goodwin became one of my favorite living players of the instrument. His solos had echoes and intimations of Bix Beiderbecke, Louis Armstrong,  Ruby Braff, Max Kaminsky and Wild Bill Davison. He wrapped all of that into a style of great individuality, intimacy, forthright conviction and humor. You can hear it in Double Play, his 1992 duo album with Frishberg. Goodwin was fairly well known in traditional jazz circles, but his playing had a universal quality that should not relegate him to a pigeonhole.

Ruby Braff, Max Kaminsky and Wild Bill Davison. He wrapped all of that into a style of great individuality, intimacy, forthright conviction and humor. You can hear it in Double Play, his 1992 duo album with Frishberg. Goodwin was fairly well known in traditional jazz circles, but his playing had a universal quality that should not relegate him to a pigeonhole.

I say "had" because Goodwin died, far too young, last month. Frishberg wrote an obituary of the friend whose work he championed and offered it to Rifftides. I don't know where else it was published, but I'm delighted to present it here. I am including Dave's information at the end, in italics, about donations and a party. I think Jim would have approved of a party.

JIM GOODWIN OBITUARYJames R. (Jim) Goodwin, the son of Katherine and Robert Goodwin, was born March 16, 1944 in Portland, OR, and died April 19, 2009 in Portland. Jim was a natural musician with no formal training. Practitioners and admirers of traditional jazz on both sides of the Atlantic have long regarded him as somewhat of a legend, and his heroic cornet playing, influenced by Louis Armstrong and Wild Bill Davison, was warmly appreciated by his musical colleagues as well as by audiences who listened and loved it.

Jim was a star first baseman at Hillsboro High-- a left-handed line-drive hitter. After high school he served in the Oregon National Guard, then trained on Wall Street for a career in finance, returned to Portland, joined Walston & Co., and became for a time the nation's youngest stockbroker. Jim then put aside the financial career and began to devote his life to playing jazz on the cornet.

During his forty-year career as a cornetist and pianist, Jim had long residencies in Breda, Holland and Berkeley, California, as well as in his home town of Portland. He played with many prominent musicians of the "old school", including Joe Venuti, Manny Klein, Phil Harris, and Portland's Monte Ballou (Jim's godfather). He toured extensively in Western Europe and became probably better known there than in the US. During his long residence in the Bay Area he played regularly at San Francisco's Fairmont Hotel and at Pier 23, as well as in three World Series with the Oakland A's pep band. Before his recent return to Portland, he spent several years living in rural Brownsmead, OR, near Astoria.

Jim became a pioneer in the Portland micro-brewing industry when, together with Fred Bowman and Art Larrance, he established the Portland Brewing Company. During the 1990s he and Portland pianist Dave Frishberg played regular duet performances at the company's Flanders Street Pub, and the two made an internationally acclaimed CD on the Arbors Jazz label.

In recent years Mr. Goodwin was on the Board of Directors of Congo Enterprises, and he served briefly as CFO of that company, leaving office months before the scandal became headline news.

**********************

Forest Park was very dear to Jim. He spent a lot of time there hiking and running.

Donations can be made to:

Forest Park Conservancy

1507 NW 23rd Avenue

Portland, OR 97210

Tel: 503-223-5449

Include a note stating that the donation is "in honor of James Goodwin".Donations may be made online at www.forestparkconservancy. A space is provided to enter the honoree's name.

There will be a party honoring Jim on Saturday, September 19th. For more information contact Retta Christie.

The Rifftides staff proudly presents the latest assortment of Doug's Picks -- three big bands, a rare Lennie Breau video and the only holdover, a book about Breau to complement the DVD. Please direct your attention to the exhibit in the middle of your screen.

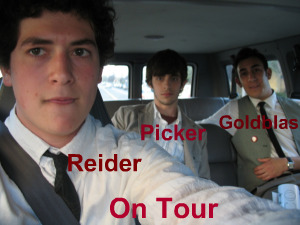

A few days short of a year ago, I told you about four 19-year-old musicians worth keeping an ear on. Three of them were the Uptown Trio, who appeared in concert supporting the gifted alto saxophonist Logan Strosahl. I wrote:

Anyone keeping a future file would do well to add those names. If these players keep developing at their current pace and intensity, it is likely that we'll be hearing from them.

I remarked in the review that pianist Sam Reider, bassist Jeff Picker (his real name) and drummer Jake Goldblas were taking the business aspect of their careers into their own hands, contacting clubs and lining up tours. Good young players not adopted by record companies and booking agents must do that to get work.

The Uptown Trio, based in New York, has arranged a west coast tour early next month, with dates at important clubs in Los Angeles, Oakland and Portland. To see their schedule and hear a bit of their music, go here.

The Uptown Trio, based in New York, has arranged a west coast tour early next month, with dates at important clubs in Los Angeles, Oakland and Portland. To see their schedule and hear a bit of their music, go here.

From a news release just received:

May 21, 2009

Washington, DC - The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) today announced the recipients of the 2010 NEA Jazz Masters Award - the nation's highest honor in this distinctly American music The eight recipients will each receive a $25,000 grant award and be publicly honored in an awards ceremony and concert on Tuesday, January 12, 2010 at Frederick P. Rose Hall, home of Jazz at Lincoln Center.The eight 2010 NEA Jazz Masters are:

Muhal Richard Abrams, pianist, composer, educator, New York, NY

Kenny Barron, pianist composer, educator, Brooklyn, NY

Bill Holman, composer arranger, saxophonist, Los Angeles, CA

Bobby Hutcherson, vibraphonist, marimba player, composer, Montara, CA

Yusef Lateef, saxophonist, flutist, oboist, composer, educator, Amherst, MA

Annie Ross, vocalist, New York, NY

Cedar Walton, pianist, composer, Brooklyn, NY

George Avakian, a jazz producer, manager, critic, and educator from Riverdale, New York, will receive the 2010 A.B Spellman NEA Jazz Masters Award for Jazz Advocacy.

Congratulations to all. To see the complete NEA announcement, click here. To read last week's Wall Street Journal profile of George Avakian by Will Friedwald, click here.

We are the masters at the moment, and not only at the moment, but for a very long time to come. -- George Bernard Shaw

No art is less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and the study of the great masters. -- Edgar Degas

A couple of years ago - maybe it was three - I linked Rifftides readers to a video so clever that it's worth bringing to you again. Now that the staff has mastered the art of embedding, this time you see it right here on our screen; no linking required. When it finishes, you will see links to other creations by the same performer, who, for a reason perhaps known only to him, calls himself "Weeping Prophet." Thanks to reader Paul Paolicelli (his real name) for reminding us of this skillful piece of work. The music is "Leap Frog" by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, with Thelonious Monk, Curly Russell and Buddy Rich (1950).

All of the tracks from the "Leap Frog" session and a wide range of Parker's other Verve recordings are in this CD set.

We did not intend Rifftides to be an obituary service. It would be simpler to avoid its seeming like one if treasured musicians would stick around. We cannot ignore their passing.

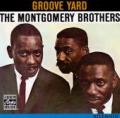

The latest loss is Buddy Montgomery, who died today at the age of 79. The youngest of the Montgomery brothers, he outlived guitarist Wes and bassist Monk by many years. Admired among musicians for his creativity as a pianist and vibraharpist, his example affected a number of younger players. The prolific pianist David Hazeltine credits Montgomery as a primary influence. In the course of a career that began in the late 1940s in his hometown of Indianapolis, Montgomery played with Big Joe Turner, Slide Hampton, Miles Davis, George Shearing, and The Mastersounds (with his brother Monk). He recorded often with his brothers and led several groups of his own.

The latest loss is Buddy Montgomery, who died today at the age of 79. The youngest of the Montgomery brothers, he outlived guitarist Wes and bassist Monk by many years. Admired among musicians for his creativity as a pianist and vibraharpist, his example affected a number of younger players. The prolific pianist David Hazeltine credits Montgomery as a primary influence. In the course of a career that began in the late 1940s in his hometown of Indianapolis, Montgomery played with Big Joe Turner, Slide Hampton, Miles Davis, George Shearing, and The Mastersounds (with his brother Monk). He recorded often with his brothers and led several groups of his own.

The Montgomery Brothers' Groove Yard album is one of their most celebrated.  The cover shows (l to r) Wes, Monk and Buddy. An extensive compilation of other music they recorded for the Riverside label has the deceptively similar name of Groove Brothers. Among Buddy Montgomery's own CDs, Here Again is a standout. Go here for a full-length sample; Montgomery with his rich harmonies on piano playing "My Ideal." Jeff Chambers is the bassist, Ray Appleton the drummer.

The cover shows (l to r) Wes, Monk and Buddy. An extensive compilation of other music they recorded for the Riverside label has the deceptively similar name of Groove Brothers. Among Buddy Montgomery's own CDs, Here Again is a standout. Go here for a full-length sample; Montgomery with his rich harmonies on piano playing "My Ideal." Jeff Chambers is the bassist, Ray Appleton the drummer.

You never know where jazz stories will materialize. This week, one about Dizzy Gillespie's hometown showed up in the travel pages of The Philadelphia Inquirer. The article by Jay Clarke of the Universal Press syndicate makes it clear that Cheraw, South Carolina, has not forgotten about its famous son; far from it. Two excerpts from Clarke's story:

Dizzy Gillespie's home no longer exists, but the site has been converted into a small park, decorated with unusual stainless-steel sculptures. One is a fence cut into the shape of a musical staff, with musical notes to Gillespie's signature work, "Salt Peanuts." A couple of others take the outline of Gillespie's trademark bent trumpet.

Downtown, a bronze statue of Gillespie, with his puffed-out cheeks and bent horn, stands in the Town Green, close to Centennial Park, where most concerts of the annual jazz festival are held. This year's fete will be Oct. 16-18.

The piece is not exclusively about Gillespie. It also covers Cheraw's Revolutionary War and Civil War history (General Sherman slept there) and its importance in the heyday of cotton. To read the whole thing, go here. There's more detail about Gillespie and the town on Cheraw's web site.

For an excellent biography of Gillespie, read Alyn Shipton's 1999 Groovin' High. Shipton discloses that in the late 1950s on one of Dizzy's many visits to Cheraw, he learned that his great-great-grandfather was a West African chief and it was likely that his great-grandfather was the white slave holder who owned Gillespie's grandmother. Gillespie's comment on that information: "That's all over the South, you know." The focus of Shipton's book, however, is less on family history than on Gillespie's music, with detailed accounts of its content and development.

For a Rifftides remembrance of Gillespie and a video clip of him playing "Tin-Tin Deo," click here.

Beginning a west coast tour, Karrin Allyson took her quartet into The Seasons Thursday evening. Alternating between bossa nova subtlety and blues forthrightness, she drew liberally from the Brazilian repertoire of her current Imagina  CD, singing in Portuguese and English. She sparkled with delicacy and brightness in Antonio Carlos Jobim classics including "Estrada Branca (This Happy Madness)," "Double Rainbow" and "Desafinado." She displayed her Kansas City roots in "Some of My Best Friends are the Blues," Ellington's "I Ain't Got Nothin' but the Blues" and Hank Mobley's "The Turnaround." She blends grit and folk wisdom into the sophistication of her blues singing and piano playing.

CD, singing in Portuguese and English. She sparkled with delicacy and brightness in Antonio Carlos Jobim classics including "Estrada Branca (This Happy Madness)," "Double Rainbow" and "Desafinado." She displayed her Kansas City roots in "Some of My Best Friends are the Blues," Ellington's "I Ain't Got Nothin' but the Blues" and Hank Mobley's "The Turnaround." She blends grit and folk wisdom into the sophistication of her blues singing and piano playing.

Guitarist Rod Fleeman and drummer Todd Strait, Allyson's colleagues since her career beginnings in Kansas City in the early 1990s, and bassist Jeff Johnson have uncanny levels of empathy with her and among one another. Allyson gave each of them extensive solo time, and each got sustained displays of enthusiasm from the audience. At one point, a Fleeman blues solo on Wes Montgomery's "Fried Pies" inspired a man sitting near me to ask no one in particular, "Where the hell did he come from?"

In Wayne Shorter's "Footprints," Allyson achieved devastating minor blues poignancy abetted by rich chord voicings in her own piano accompaniment. Asked in a post-intermission chat about the increased depth of her piano playing, she seemed taken aback, as if it were being called to her attention for the first time. In fact, she is a piano soloist and accompanist of fluency and harmonic resourcefulness. Allyson's concert was a demonstration of the completeness of her musicianship as a vocalist, a pianist, and a leader who inspires and interacts with her sidemen. Her group is a band, in every sense. She elicited two standing ovations, gave two encores and left the audience hoping for more.

Tonight, Allyson and company perform at the San Francisco Jazz Festival. To see if they're coming to a town near you, check their itinerary.

Driving home following the Allyson concert (and a fine hang over a good glass of Washington wine), I turned on the radio. The classical station was playing Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony. As I crested a hill, there was the full moon, filling half the sky. At that moment, the orchestra reached the horn arietta in the second movement, the one that inspired Andre Kostelanetz to steal from Peter Ilyitch and write "Moon Love." In the video clip below, Leonard Bernstein conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Although the "Moon Love" melody comes at 7:30, I strongly urge you to watch the entire clip to appreciate how Bernstein and the BSO build to the moment. The clip ends prematurely, but what we get is splendid.

To hear what Chet Baker did in 1953 with the standard song based on the Tchaikovsky melody, click here, then on the play arrow in the box at the upper right of your screen. This is a prime example of a jazz artist recognizing that, sometimes, unadulterated melody is the purest statement he can make. The pianist is Russ Freeman, the bassist Carson Smith, the drummer Larry Bunker.

Ken Poston of the Los Angeles Jazz Institute sent information about the tribute later this month to Bud Shank. The great alto saxophonist and flutist died on April 2.

The Bud Shank Memorial Concert is scheduled to take place May 23rd at7:00pm at The Four Points Sheraton at LAX 9750 Airport Blvd. It's happening during the upcoming "A Swingin' Affair" festival but will be free and open to the public. Numerous musicians are performing, including Bud's original rhythm section: Claude Williamson, Don Prell and Chuck Flores and his latest rhythm section with Bill Mays and Bob Magnusson.

Bud Shank Memorial Concert

May 23 7:00-9:00PM

Four Points Sheraton at LAX

9750 Airport Blvd.

Los Angeles, CAFREE

Featured artists and speakers include:

Howard Rumsey

Claude Williamson

Don Prell

Chuck Flores

Clare Fischer

Dennis Budimer

Bill Mays

Bob Magnusson

Lanny Morgan

Pete Christlieb

Fred Selden

Doug Webb

Jack Nimitz

Bill Ramsay

David Friesen

For the Rifftides remembrance of Shank and comments from readers, go here.

Here's Shank in the early sixties when he collaborated with pianist-composer Clare Fischer. The unannounced bassist and drummer appear to be Gary Peacock and Larry Bunker. I cannot identify the hand percussionist.

Bill Kirchner continues his Jazz From The Archives series on WBGO-FM, Newark, (88.3) and the internet with a show about a musician frequently mentioned on Rifftides. Here's his announcement.

Musician/author Richard Sudhalter (1938-2008) wrote (in the first case, co-wrote) three landmark books: BIX: MAN AND LEGEND, LOST CHORDS, and STARDUST MELODY. He also was a fine jazz cornetist in the Bix Beiderbecke/Bobby Hackett mold. As a musician, he had wide-ranging stylistic interests and was difficult to pigeonhole.

We'll hear recordings by Sudhalter as a leader and as a member of the Classic Jazz Quartet (with clarinetist Joe Muranyi, pianist Dick Wellstood, and guitarist Marty Grosz). The repertoire ranges from rareties of the 1920s to tunes by Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, and Gerry Mulligan, as well as Sudhalter originals.The show will air this Sunday, May 10, from 11 p.m. to midnight, Eastern

Daylight Time.NOTE: If you live outside the New York City metropolitan area, WBGO also

broadcasts on the Internet at www.wbgo.org. Click on "Listen Now" at the top of the WBGO home page.

For the Rifftides remembrance of Sudhalter on his passing last year, click here.

Paul Paolicelli and I got to be friends hanging out at professional meetings when we were television news directors. We were both trumpet players and found more to talk about than the state of journalism, which in the 1970s and '80s was already a little soft around the edges. Come to think of it, so was the jazz business.

Paul still runs a TV news operation, in North Carolina, and has a blog on his station's web site. This morning he responded to the "Giant Steps" piece below by referring me to his latest entry, which begins:

A few years ago I told my (soon to be 13 year old) daughter that one of the few things Icould truly give her was a working understanding of the difference between John Coltrane and Paul Desmond. That she probably had no idea of what I was talking about, but that one day in a distant future, when she would be able to glibly discuss jazz with a full memory of the sounds, and she'd smile and thank me wherever I might be by then.

Sometimes things happen sooner than later.The other day my daughter and I were driving to Wilmington from Chapel Hill and listening to Anita O'Day (I have a car loaded with CDs and mp3s of the old jazz greats, just for this purpose)...

To find out what happened then, go here.

To find out more about Paolicelli, go here.

John Coltrane's "Giant Steps" is the harmonic steeplechase generally regarded as the most significant - at least the most prominent - milestone on the tenor saxophonist's path out of bebop on his way to what he called a universal sound. Difficult as the fact may be to absorb for those still bowled over by the freshness and complexity of what Coltrane did with the piece, he made his stunning recording of "Giant Steps" 50 years ago today.

To put the lasting impact of his accomplishment in perspective, think of an influential jazz recording made 50 years before Coltrane laid down "Giant Steps" on May 5, 1959. You can't. There was none, because jazz as a distinct form of music did not exist on May 5, 1909. "Giant Steps" is a monument to the evolution of the art of jazz in less than half a century, a phenomenon unprecedented in any other fundamental genre of music. Coltrane's rhythm section was Tommy Flanagan, piano; Paul Chambers bass; Arthur Taylor, drums. It has sometimes been pointed out that in his solo Flanagan seems less than comfortable with the changes. If you are a musician, imagine how comfortable you would be negotiating that minefield of chords if the music were set before you for the first time at a record session.

To put the lasting impact of his accomplishment in perspective, think of an influential jazz recording made 50 years before Coltrane laid down "Giant Steps" on May 5, 1959. You can't. There was none, because jazz as a distinct form of music did not exist on May 5, 1909. "Giant Steps" is a monument to the evolution of the art of jazz in less than half a century, a phenomenon unprecedented in any other fundamental genre of music. Coltrane's rhythm section was Tommy Flanagan, piano; Paul Chambers bass; Arthur Taylor, drums. It has sometimes been pointed out that in his solo Flanagan seems less than comfortable with the changes. If you are a musician, imagine how comfortable you would be negotiating that minefield of chords if the music were set before you for the first time at a record session.

I am not sure that the video clip below explains what about "Giant Steps" led to an opening up of the approach to jazz improvisation. Indeed, I am not sure that Coltrane's artistry can be explained; the quotients of mystery and spirit in his music are as essential as his quantifiable elements of musicianship and saxophone technique. The clip certainly shows what his astonishing solo on the piece is made of. Thanks to longtime Rifftides reader Dick McGarvin for bringing this to our attention. Hold onto your seats and, as Dick says, follow the bouncing ball.

After you have played or sung along with Coltrane, you may wish to take a few moments to read some of the more than 1,500 comments from YouTube viewers about "Giant Steps." They range from the simplistic but inarguable:

this is really coool ..

To those that will boggle the minds of laymen:

Look for the tonal centers. The starting B chord throws people off, it can be treated as a Bmin7, giving you 6 beats in G, 6 beats in Eb, 6 beats in G, 4 beats in Eb and 4 beats in B; then 8 beats in Eb, 8 beats in G, 8 beats in B, 8 beats in Eb. The last bar is a turnaround in B to bring you back to the initial chord- you can play the D# to D to emphasize the change in tonal center or play a B. Find the pivot tones that adjacent tonal centers have in common to play across the bar lines.

En masse, the comments emphasize the impression that Coltrane's performance has made on jazz listeners and jazz players, most of whom were probably not born when he recorded it.

The album Giant Steps is a basic repertoire item, a necessity in any serious collection.

"Giant Steps" led the artist Michal Levy to create an inspired film animation based on an abbreviated version of Coltrane's recording. Her work is in the spirit, but not the style, of the pioneering Canadian artist Norman McLaren. To see Levy's piece, go here.

You may have been wondering why, to submit a comment to Rifftides, you are asked to type in a box two words like these samples.

A curious and, possibly, irritated reader asked,

Isn't it funny when they want you to type in the words at the bottom - it's like a "TEST" to see if you can make them out? Why don't they make it easy for us?Why is that? We can't cheat. We are on our own computers. That is so funny isn't it?

It's not so funny if spammers grab your e-mail address and plague you with junk mail. Artsjournal.com Commander-In-Chief Doug McLennan explains:

They have to make them obscure enough so that computer spam bots can't read them. That's the whole point. Modern scanner algorithms can read images that are clear. This captcha program is supposed to be one of the best.

I hope that you feel safer. Test the system; click the Comments link below and send one. We're always glad to have Rifftides readers' opinions and observations.

Last Friday, Leonard Lopate of WNYC radio in New York invited Bill Charlap to drop by  the studio where Lopate does his Please Explain program and talk about how jazz improvisation works. Seated at the piano, Charlap spoke clearly about the raw materials of music and showed what jazz players do with them in the act of creation. He used "These Foolish Things" and the blues as his demonstration models. Lopate, a personification of the inquiring mind, asked good questions. He reached a couple of layman's conclusions with which Charlap

the studio where Lopate does his Please Explain program and talk about how jazz improvisation works. Seated at the piano, Charlap spoke clearly about the raw materials of music and showed what jazz players do with them in the act of creation. He used "These Foolish Things" and the blues as his demonstration models. Lopate, a personification of the inquiring mind, asked good questions. He reached a couple of layman's conclusions with which Charlap politely and firmly disagreed. Toward the end of the half hour of good conversation and music, Lopate and Charlap took a few calls from canny listeners. It is all entertaining and instructive, even for those who may know, or think they know, the answers. To hear the program, click on the arrow in the box below. You will get a brief WNYC promotional announcement, then the show.

politely and firmly disagreed. Toward the end of the half hour of good conversation and music, Lopate and Charlap took a few calls from canny listeners. It is all entertaining and instructive, even for those who may know, or think they know, the answers. To hear the program, click on the arrow in the box below. You will get a brief WNYC promotional announcement, then the show.

Thanks to Julius LaRosa for pointing us toward a performance with the Oscar Peterson Trio by Ella Fitzgerald late in her career. Peterson sits out most of the first chorus. Bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen generates the powerful swing with Fitzgerald. Then the pianist and drummer Martin Drew join the ride. Ella is rarely singled out for her low-register chops, but take notice of her deep range in the third chorus.

Have a good weekend.

The White House has yet to award a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom to Willis Conover. But there has been progress toward that goal. I was delighted to learn when I got off the road this week that Congress proclaimed April 25 Willis Conover Day. He was honored during celebrations on the National Mall. Finally, his nation has given official recognition to the Voice Of America broadcaster who sent jazz to the world and, without indulging in propaganda or politics, helped to end the Cold War. Here is part of one of many Rifftides items about Conover.

Through most of the cold war, Conover was the host of Music USA on the Voice of America. He was never a government employee, always working under a free lance contract to maintain his independence. While our leaders and those of the Soviet bloc stared one another down across the nuclear abyss, in hisstately bass-baritone voice Willis introduced listeners around the world to jazz and American popular music. With knowledge, taste, dignity and no trace of politics, he played for nations of captive peoples the music of freedom. He interviewed virtually every prominent jazz figure of the second half of the twentieth century. Countless Eastern European musicians give him credit for bringing them into jazz. Because the Voice is not allowed to broadcast to the United States, Conover was unknown to the citizens of his own country. For millions behind the iron curtain he was an emblem of America, democracy and liberty. Gene Lees makes the case, to which I subscribe wholeheartedly, that,

...Willis Conover did more to crumble the Berlin wall and bring about collapse of the Soviet Empire than all the Cold War presidents put together.

To read all of that item, follow this link.

Below is a video broadcast in Russian following a Washington, DC, concert in the fall of 2007, honoring Conover's memory. It gives us a glimpse of Willis at work in his VOA studio not long before his death in 1996. As a direct result of listening to Conover's VOA programs, the players in the concert all developed as jazz musicians behind the iron curtain. They are Paquito D'Rivera, alto saxophone (Cuba); Valery Ponomarev, trumpet (Soviet Union); Milcho Leviev, piano (Bulgaria); George Mraz, bass (Czechoslovakia); Horacio Hernandez, drums (Cuba). The piece is Ellington's "Take the 'A' Train," the theme music for Conover's Music USA.

This gathering of world-class artists inspired by Conover to become jazz musiciains expresses more powerfully than any congressional resolution his contribution to US cultural diplomacy. Still, that presidential Medal of Freedom is long overdue.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary