main: February 2009 Archives

Over the years, Honda has called several vehicles, including a motorcycle, Jazz. Now Renault, the French auto maker, has unveiled a new model in its Kangoo line and named it the Be Bop.

Could Renault's move kick-start a trend? How about:

Mercedes Swing

Hyundai Stride

BMW Boogie-Woogie

Chrysler Blues

Mini Cooper Trad

Chevrolet Cool

GM Groove

Porsche Scat

Volvo Vouty

For Shorty Rogers fans, the Infiniti Promenade

The Renault web site indicates that the Be Bop is available in much of the world, but not in the United States, the land where its namesake originated.

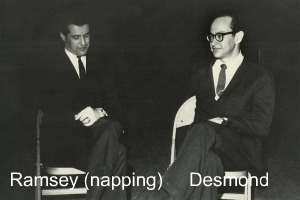

In the past few days, three videos have materialized of a 1956 television performance by the Dave Brubeck Quartet. They show the group after Brubeck was elevated to general fame by way of a TIME magazine cover story but before Joe Morello and Eugene Wright replaced Joe Dodge and Norman Bates on drums and bass. As I wrote in Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond,

It may be difficult for anyone who grew up after the pervasive hype of television and the omnipresence of the internet diluted the impact of print, to understand the power of a cover story in TIME. It brought massive attention to the subject and made him, or her, an instant celebrity. Brubeck's career had begun to show that it had the potential for steady, respectable growth. Now it took off. Sales of his records leaped, not only of the new Columbias with Desmond, Bates and Dodge, but the Fantasys as well. The Quartet's bookings increased and its fees grew exponentially.

Dodge resigned and Morello came aboard in the fall of '56, so the TV program was most likely in the spring or summer of that year. As too frustratingly often with You Tube, the person who posted the videos gives no information about the program - not the date, the name of the show, the name of the host, the call letters of the station or the name of the city. I am attempting to dig up those facts. Stay tuned.

Of course, the music is what matters. The importance of Bates and Dodge to the early quartet has been obscured by the attention given Wright and Morello in the "classic" Brubeck Quartet following the massive success of "Take Five" in the early sixties. This is a rare chance to see Bates and Dodge and hear what a well-integrated band this was. To eliminate the bother of following links to YouTube, the Rifftides public service department brings you all three segments, totaling nearly 25 minutes. Enjoy.

If anyone out there in the blogosphere knows the missing who, when and where of these clips, please use the Comments link below.

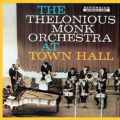

Tonight and tomorrow night, Town Hall in New York City is observing the fiftieth anniversary of Thelonious Monk's celebrated performance there with a ten-piece band. This evening's concert will present trumpeter Charles Tolliver's big band playing Monk's music. WNYC will broadcast it live at eight o'clock EST. To hear it in the New York area, tune in to 93.9 FM. To hear it on the internet, go here.

Tomorrow night, pianist Jason Moran will lead an eight-piece ensemble in what is being described as a concert and media-collage. Both concerts will use W. Eugene Smith's photographs of Monk and orchestrator Hall Overton as they created medium-size-band arrangements of Monk's compositions. WNYC will record Moran's concert and may broadcast it later.

Yesterday, Moran was in WNYC's studios for the Leonard Lopate Show, discussing and demonstrating the challenges of interpreting Monk. Lopate brought in cameras, resulting in radio with pictures. Moran's sidemen are alto saxophonist Logan Richardson, tenor saxophonist Aaron Stewart, bassist Tarus Mateen and drummer Nasheet Waits.

The recording of Monk's Town Hall concert of February 28, 1959, is a basic repertoire item for any serious listener.

The recording of Monk's Town Hall concert of February 28, 1959, is a basic repertoire item for any serious listener.

Howard Mandel suffered a transportation glitch, but gamely picked up the reporting on the Portland Jazz Festival that I left dangling. The proprietor of Jazz Beyond Jazz, Howard does a fine job of pulling together the loose Portland ends. He manages to incorporate three video clips, including one of Laurel and Hardy that I could watch all night. To see his omnibus piece, click here.

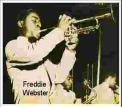

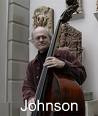

Every few years, there is a Freddie Webster revival, of sorts. In recent weeks, through internet contact jazz musicians, researchers and writers have again been discussing Webster, the trumpeter generally thought to have been an influence on Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. Webster died in 1947 at the age of 30. If you have been told or read about Webster but never heard him, David Brent Johnson offers the opportunity to listen to just about everything the trumpeter recorded. In 2005, Johnson devoted an hour to Webster on his Night Lights program. Between recordings, he provides considerable biographical information. To hear the archived program on Johnson's web site, click here. See if you detect the pre-bebop ideas that may have inspired Davis and Gillespie.

Every few years, there is a Freddie Webster revival, of sorts. In recent weeks, through internet contact jazz musicians, researchers and writers have again been discussing Webster, the trumpeter generally thought to have been an influence on Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. Webster died in 1947 at the age of 30. If you have been told or read about Webster but never heard him, David Brent Johnson offers the opportunity to listen to just about everything the trumpeter recorded. In 2005, Johnson devoted an hour to Webster on his Night Lights program. Between recordings, he provides considerable biographical information. To hear the archived program on Johnson's web site, click here. See if you detect the pre-bebop ideas that may have inspired Davis and Gillespie.

Viewing Tip

The current offering on Bret Primack's web site is a video in which the Blue Note 7 all-stars play a complete performance of Thelonious Monk's "Criss Cross." It is worth your time. To see it, click here.

For the Rifftides review of a Blue Note 7 concert as they got underway with their national tour, go here.

When I was looking for something on You Tube the other night, what to my wondering eyes should appear but the Kessler Sisters. I hadn't seen them in forty years, and they still looked terrific. Paul Desmond introduced me to them in 1965 at the Hilton Hotel in Portland, Oregon. Desmond had just played a concert with the Dave Brubeck Quartet at Willamette University down the road in Salem. I couldn't go because I was working. When I got off the air, I met him for a drink. Here's the story from Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond.

In the Hilton bar, he was high on the success of the concert he had just played and delighted to see the Kessler sisters again. The Scopitone was a film jukebox. The first ones were made in France, in part from used World War Two airplane reconnaissance camera equipment. The more finished version that made its way fromEurope to the United States in 1963 looked rather like a big old soda fountain Wurlitzer with a screen at the top. Scopitone films on sixteen milimeter stock with magnetic sound tracks ran on endless loops through a projector inside the jukebox. They were descendants of the Nickelodeons of the first decade of the twentieth century and the soundies of the thirties and forties, and ancestors of the music videos seen on MTV and VH-1. French businessmen persuaded U.S. investors, who in turn persuaded bar and lounge operators, that Scopitone was going to get Americans away from their television sets and back out to night life. The films ran two or three minutes, with production values on a scale from almost absent to spectacular, and featured artists with talent to match. At the low end of the scale were groups like The Casualeers singing on a fire escape while two mostly nude girls gyrated. At the upper end were Scopitones starring the Kessler sisters, a pair of blonde, leggy young women who sang and danced with exhilarating zeal through pieces like "Cuando, Cuando" and "Pollo e Champagne."

Desmond pumped quarters into the Hilton Scopitone, sending the Kessler Sisters cavorting again and again through an amusement park, singing as they leapt on and off a train, with a corps of dancers in the background executing routines that would have done Busby Berkeley proud. He was convinced that the Scopitone was going to be bigger than television and almost had me persuaded that we should invest large sums in the phenomenon. The more Dewars we had, the more sensible the investment plan became. Fortunately, the Oregon closing law kicked in before I committed to anything irrevocable. I don't know whether Paul signed up for a share of the company, but I am glad that I didn't. By the end of the decade, Scopitones were gathering dust in warehouses all over the world.

In today's Los Angeles Times, David Ritz writes from a personal standpoint about the nearly simultaneous loss of three important musicians. Ritz is the author or co-author of several books about blues and soul artists including Ray Charles. The headline on his op-ed piece is "Ray Charles' Heavenly Trio." Here's the first paragraph:

In today's Los Angeles Times, David Ritz writes from a personal standpoint about the nearly simultaneous loss of three important musicians. Ritz is the author or co-author of several books about blues and soul artists including Ray Charles. The headline on his op-ed piece is "Ray Charles' Heavenly Trio." Here's the first paragraph:

In summer 1957, I was a teenager who had just moved to Texas from the East Coast. One Sunday afternoon, I happened to walk into a large social hall in South Dallas where a jam session was underway. On the bandstand were three saxophonists: Leroy "Hog" Cooper on baritone, David "Fathead" Newman on tenor and Hank Crawford on alto.

To read the whole thing, go here. For the Rifftides remembrance of Newman, and a performance video, go here.

Earlier this week, Dick Hyman played a noontime recital at a church in Manhattan. Fellow artsjournal blogger Jan Herman was there with his camera and posted videos of Hyman playing Fats Waller's "My Fate Is In Your Hands" and "Bach Up To Me." To see Jan's piece and hear Hyman, go here.

When you come back, if you want more Waller -- and, of course, you will -- click on these links to hear Fats play:

"My Fate Is In Your Hands,

" Valentine Stomp" (take one)

and

"Valentine Stomp" (take two), all from 1929.

There. Now, don't you feel better?

Final report on the opening days of the Portland Jazz Festival:

In elegant Schnitzer Hall, clarinetist and tenor saxophonist Don Byron had Edward Simon on piano and Eric Harland on drums in his Ivey-Divey Trio. It was the same instrumentation as the Gross-Frishberg-Doggett trio that played the night before in quite different circumstances (see Part 2). In makeup, feeling and interaction, both groups reflect the Lester Young-Nat Cole-Buddy Rich trio of the mid-1940s. Their lead voices, respectively Byron and John Gross, revel in taking harmony and phrasing over the edge of convention. Gross does it with no physical motion beyond what is necessary to operate his saxophone. Byron moves constantly, bobbing, weaving, dancing, conducting with body language. It would be interesting to hear and see these two adventurers together.

In elegant Schnitzer Hall, clarinetist and tenor saxophonist Don Byron had Edward Simon on piano and Eric Harland on drums in his Ivey-Divey Trio. It was the same instrumentation as the Gross-Frishberg-Doggett trio that played the night before in quite different circumstances (see Part 2). In makeup, feeling and interaction, both groups reflect the Lester Young-Nat Cole-Buddy Rich trio of the mid-1940s. Their lead voices, respectively Byron and John Gross, revel in taking harmony and phrasing over the edge of convention. Gross does it with no physical motion beyond what is necessary to operate his saxophone. Byron moves constantly, bobbing, weaving, dancing, conducting with body language. It would be interesting to hear and see these two adventurers together.

Byron opened with "Lefty Teachers at Home" from his 2004 Ivey-Divey CD. The piece has evolved harmonically, with even greater chance-taking than in the recording. Then came "Fosberry Flop." Introducing it, Byron suggested that just as Dick Fosberry's unorthodox style revolutionized high-jumping, the piece involved turning around aspects of Arnold Schoenberg. That qualifies as counter-revolutionary. The trio's use of dynamics was most dramatic in "Fosberry," Harland ending a solo with a crescendo that

dynamics was most dramatic in "Fosberry," Harland ending a solo with a crescendo that

Byron and Simon followed so softly that their re-entry would have to be notated pppp. Then came a three-way conversation in which, as he made his points, Simon dominated and receded, swelled and diminished. The pianist was impressive throughout the set and evidently having a splendid time. He rarely stopped smiling.

"Somebody Loves Me" was laced with boom-chicky rhythms that Byron, Simon and Harland managed to make both evocative of earlier jazz and as hip as tomorrow. They  generated powerful swing, with solos from Byron on clarinet and tenor, Harland commenting and interjecting, and Simon's full-bodied playing a revelation. Has Simon slipped under the radar or have I been missing his growth from a good into a master jazz player? Byron's tenor work was fine. His clarinet playing was brilliant. He wound up his set with what he described as a "chain gang" piece in which he recruited the audience of more than 2,000 as a percussion section, clapping time.

generated powerful swing, with solos from Byron on clarinet and tenor, Harland commenting and interjecting, and Simon's full-bodied playing a revelation. Has Simon slipped under the radar or have I been missing his growth from a good into a master jazz player? Byron's tenor work was fine. His clarinet playing was brilliant. He wound up his set with what he described as a "chain gang" piece in which he recruited the audience of more than 2,000 as a percussion section, clapping time.

When he was through, Byron referred to the next artist as "the greatest pianist in the world." That was McCoy Tyner, presented as co-leader of a quartet with Joe Lovano. It was the last of Lovano's four major appearances at the Portland Festival. Bassist Gerald Cannon and drummer Eric Gravatt, stalwarts of post-Coltrane jazz, rounded out the rhythm section. Much of the music was from Tyner's 2007 CD with Lovano, and some of the pieces they played go back as far as his 1967 album The Real McCoy.

No saxophonist can work with Tyner and avoid comparison with John Coltrane, but as Joe Henderson and Michael Brecker had before him in their collaborations with Tyner, Lovano has long since worked through his Coltrane apprenticeship. Even on "Moment's Notice," the one Coltrane composition in the concert, there was no sense of Coltrane's spirit riding on Lovano's shoulder. He and Tyner have developed their own relationship. It involves more by-play and humor than existed in the classic Coltrane quartet.

As in most of his work for the past couple of decades,Tyner's hallmarks were strength and volume, but in "Moment's Notice" he shifted down for a solo of clarity with single note lines rather than unremitting successions of power chords. He reached the concert's apogee of muscular playing in "Angelica," which also had a commanding Cannon bass solo. Then came Tyner's only unaccompanied piece and only standard song of the evening. In "For All We Know," he disclosed more about his early piano influences than we usually hear. Intensity drained away for a few minutes and his playing was utterly relaxed. It encompassed moments when Teddy Wilson might have been at the keyboard and others when Tyner took his listeners even further back in the history of jazz piano, to the stride era. It was a change of pace, good programming and a glimpse of a facet of Tyner's musical makeup that is usually under cover.

Cannon bass solo. Then came Tyner's only unaccompanied piece and only standard song of the evening. In "For All We Know," he disclosed more about his early piano influences than we usually hear. Intensity drained away for a few minutes and his playing was utterly relaxed. It encompassed moments when Teddy Wilson might have been at the keyboard and others when Tyner took his listeners even further back in the history of jazz piano, to the stride era. It was a change of pace, good programming and a glimpse of a facet of Tyner's musical makeup that is usually under cover.

For "Blues on the Corner," it was back to post-bop business, with chops flying everywhere, to borrow Louis Armstrong's immortal phrase; plenty of exchanges between Tyner and Lovano with each smiling at the other's phrases, another sturdy bass solo by Cannon, and drum explosions from Gravatt. The encore, following insistent applause, was one of Tyner's signature compositions, "Fly With the Wind"

For "Blues on the Corner," it was back to post-bop business, with chops flying everywhere, to borrow Louis Armstrong's immortal phrase; plenty of exchanges between Tyner and Lovano with each smiling at the other's phrases, another sturdy bass solo by Cannon, and drum explosions from Gravatt. The encore, following insistent applause, was one of Tyner's signature compositions, "Fly With the Wind"

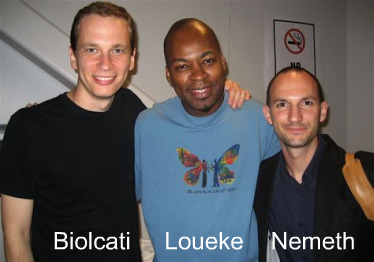

The publicity surrounding and following Lionel Loueke's signing with Blue Note Records made it seem that the guitarist from Benin in West Africa had materialized unexpectedly. However, he is an overnight sensation with a deep background in music. It includes higher education in Europe, studies at Berklee College of Music and the Thelonious Monk Institute, and experience with Terence Blanchard's sextet. He and his trio mates met in Paris and have been playing together for more than a decade.

All of that time in yoke accounts for the polish in their performance, and for their empathy. In the three pieces I heard them play in Portland, it was clear that, with bassist Massimo Biolcati and drummer Ferenc Nemeth, Loueke has merged his African heritage and his jazz knowledge in a synthesis that gives his trio a sound and identitiy that qualifiy them for that abused adjective, unique.

Trying to determine whether they play jazz is as pointless as trying to define jazz itself. They play improvised music that allows freedom within structures, and both aspects of their work are compelling. Loueke's style encompasses rhythm guitar as well as a highly individual way of gliding through chord patterns. It is unlike the work of any other guitarist with whom I am familiar. His singing, sometimes integrated with simultaneous vocal clicks, is intriguing and, as far as I could tell on short exposure, not included as a novelty but as an integral part of his performance.

Biolcati and Nemeth are first-class players who listen closely to Loueke and each other. They all throw rhythmic suprises to and fro, to their apparent pleasure and satisfaction. It's a serious and entertaining band. The songs they played, "Karibu," "Benny's Tune" and "Seven Teens," are all from the Loueke trio's most recent CD. I liked what I heard in Portland and I'm going to spend a little time with their album to get to know them better.

The PDX festival continues this weekend. My fellow artsjournal.com blogger Howard Mandel is there. Maybe he'll pick up the cudgel and let us know what happens.

Further reflections on highlights of the festival's first weekend:

Gonzalo Rubalcaba opened the first major concert of the festival with a band of young sidemen who are in the thick of the latterday New York Latin jazz explosion that is producing some of the most important music of the new century. The virtuoso pianist's quintet is twice or three times removed from the Charlie Parker-Dizzy Gillespie generation but it has a distinct bebop lineage, particularly in the ensembles. The rhythms are manifestations of the various Cuban traditions of which Rubalcaba is a master. The Rubalcaba band's melding of the two strains produces harmonic astringency and irresistible time feeling. Alto saxophonist Yosvany Terry, bassist Yunior Terry and drummer Ernesto Simpson are Rubalcaba's fellow Cubans. Trumpeter Michael Rodriguez is a New Yorker fully immersed in the Latin mainstream and, like Terry, a soloist who seems bound to become a major figure.

Gonzalo Rubalcaba opened the first major concert of the festival with a band of young sidemen who are in the thick of the latterday New York Latin jazz explosion that is producing some of the most important music of the new century. The virtuoso pianist's quintet is twice or three times removed from the Charlie Parker-Dizzy Gillespie generation but it has a distinct bebop lineage, particularly in the ensembles. The rhythms are manifestations of the various Cuban traditions of which Rubalcaba is a master. The Rubalcaba band's melding of the two strains produces harmonic astringency and irresistible time feeling. Alto saxophonist Yosvany Terry, bassist Yunior Terry and drummer Ernesto Simpson are Rubalcaba's fellow Cubans. Trumpeter Michael Rodriguez is a New Yorker fully immersed in the Latin mainstream and, like Terry, a soloist who seems bound to become a major figure.

A typical piece in a Rubalcaba concert begins with the pianist unaccompanied in a meditation at the keyboard. Gradually, his playing takes on rhythmic character that intensifies as bass and drums undergird the time. Trumpet and alto saxophone express the melodic line harmonized or in unison, then solo at length. In some pieces there are drum or bass solos. Rubalcaba often chooses to go last in the solo sequence.

The other night, Yosvany Terry blew billows and clusters of notes with a vigor that often bordered on ferocity. Rodriguez was more considered in his note choices but played with nearly equal force and with excursions into the stratospheric range that seems to be standard equipment for young trumpeters. Simpson's roiling drum patterns urged them on. There may be no pianist at work today with more technique than Rubalcaba. He astonishes listeners with his command of the instrument. And yet, when he solos following the elation of a drum, bass, trumpet or saxophone solo by one of his sidemen, the level of passion drops. It may be that he means to create contrast. In any case, for all of the beauty of his playing, in his solos the emotional level of the music subsides. Judging by their reaction, the Portland audience didn't notice that, or it didn't matter to them. Rubalcaba and the band received thunderous applause and a standing ovation.

bordered on ferocity. Rodriguez was more considered in his note choices but played with nearly equal force and with excursions into the stratospheric range that seems to be standard equipment for young trumpeters. Simpson's roiling drum patterns urged them on. There may be no pianist at work today with more technique than Rubalcaba. He astonishes listeners with his command of the instrument. And yet, when he solos following the elation of a drum, bass, trumpet or saxophone solo by one of his sidemen, the level of passion drops. It may be that he means to create contrast. In any case, for all of the beauty of his playing, in his solos the emotional level of the music subsides. Judging by their reaction, the Portland audience didn't notice that, or it didn't matter to them. Rubalcaba and the band received thunderous applause and a standing ovation.

The second half of the opening night concert was trumpeter and composer Terence Blanchard's post-hurricane lament for his home town, New Orleans. As in the CD of the work, "A Tale of God's Will (A Requiem for Katrina)" presented Blanchard's quintet and a 40-piece orchestra. Written by Blanchard and members of his band, the music expresses the grief, anger and frustration that dominated the city in the wake of Katrina and the Bush administration's botched response to the disaster. Painfully, New Orleans is recovering from both. A thirteen-movement suite, "A Tale of God's Will" has uplifting moments as well as dirges, but Blanchard delivered the uplift on waves of anger expressed not only in his playing, but also in spoken sentiments onstage. Still, passages of quiet beauty remain in the mind, notably in Aaron Parks' "Ashé" and in "Dear Mom," Blanchard's portrayal of his mother's ordeal in the flooding of New Orleans.

expresses the grief, anger and frustration that dominated the city in the wake of Katrina and the Bush administration's botched response to the disaster. Painfully, New Orleans is recovering from both. A thirteen-movement suite, "A Tale of God's Will" has uplifting moments as well as dirges, but Blanchard delivered the uplift on waves of anger expressed not only in his playing, but also in spoken sentiments onstage. Still, passages of quiet beauty remain in the mind, notably in Aaron Parks' "Ashé" and in "Dear Mom," Blanchard's portrayal of his mother's ordeal in the flooding of New Orleans.

Blanchard's orchestral writing, still evolving, sometimes bypasses the potential for harmonic depth and variety in the string section, but when he brings in the brass, he achieves moments of swelling grandeur. It is mystifying why Blanchard or the concert producer thought it was necessary to amplify the orchestra. In the good acoustics of Schnitzer Hall, the balance between soloists and orchestra would have been better au naturale. Blanchard's excessive use of slurs and scoops in his playing has always disturbed me. In "Levees," with its echoes of "St. James Infirmary," the slurs were effective. Nonetheless, as they accumulated through the concert, they amounted to a distraction.

Bassist Derrick Hodge and drummer Kendrick Scott have been with Blanchard for some time. Pianist Fabian Almazan and young tenor saxophonist Walter Smith are new to the band. All played beautifully in a work whose substance should give it a life beyond its timeliness as commentary on a tragedy.

In her concert at the Schnitzer, Dianne Reeves did what she does best. She sang good songs simply. Accompanied by her trio and the Oregon Symphony orchestra conducted by Gregory Vajda, Reeves avoided the gospel and soul affectations that have sometimes marred her work and employed her glorious voice in the interpretation of standards appropriate to Valentine's Day. She included "I Remember Sarah," which she wrote with Billy Childs, and followed it with an engagingly self-deprecating anecdote about her first encounter with Sarah Vaughan, her idol, when Reeves was a teenager.

In her concert at the Schnitzer, Dianne Reeves did what she does best. She sang good songs simply. Accompanied by her trio and the Oregon Symphony orchestra conducted by Gregory Vajda, Reeves avoided the gospel and soul affectations that have sometimes marred her work and employed her glorious voice in the interpretation of standards appropriate to Valentine's Day. She included "I Remember Sarah," which she wrote with Billy Childs, and followed it with an engagingly self-deprecating anecdote about her first encounter with Sarah Vaughan, her idol, when Reeves was a teenager.

Thad Jones' "A Child Is Born" and Gerhswin's "Embraceable You" were high points. Both had affecting piano solos by Peter Martin. Martin, with her other longtime trio members bassist Reuben Rogers and drummer Kendrick Scott, backed Reeves with what may have been extrasensory perception. It was, hands down, the best I have ever heard her sing. Reeves' performance was an emotional experience for her and her audience.

At the Portland Art Museum, guitarist John Scofield had bassist Matt Penman and  drummer Bill Stewart in his trio. With the tonal qualities of a hip hurdy-gurdy, his daring intervals and thrilling runs, Scofield delivered a concert packed with intensity and good-natured swing. Continuing his ubiquitousness, Joe Lovano sat in with his old friend and recording partner for a not-quite-impromptu meeting of their mutual admiration society. Lovano, who evidently either never forgets a tune or can absorb and perform one simultaneously, was in lockstep with Scofield on complex melody lines. They had a great time entertaining one another and the audience. Penman and Stewart were in equally fine fettle.

drummer Bill Stewart in his trio. With the tonal qualities of a hip hurdy-gurdy, his daring intervals and thrilling runs, Scofield delivered a concert packed with intensity and good-natured swing. Continuing his ubiquitousness, Joe Lovano sat in with his old friend and recording partner for a not-quite-impromptu meeting of their mutual admiration society. Lovano, who evidently either never forgets a tune or can absorb and perform one simultaneously, was in lockstep with Scofield on complex melody lines. They had a great time entertaining one another and the audience. Penman and Stewart were in equally fine fettle.

Meanwhile, at the Art Bar of the Portland Center for the Performing Arts, the cooperative trio of tenor saxophonist John Gross, pianist Dave Frishberg and drummer Charlie Doggett were playing to a modest crowd until the Scofield concert ended. Then, the bar in the PCPA atrium filled up with thirsty musicians and others, some of whom paid attention to the music, which was a good idea, because it was remarkable. Gross,  who made his mark in the most avant garde band Shelly Manne ever had, is a tenor saxophonist who calmly and with a rich tone plays iconoclastic ideas. Frishberg is a celebrated performer of his own songs whose policy is never to sing in Portland, his home town. He does, however, accept gigs there as a pianist. He is one of the best pianists in the mainstream. Doggett is a young drummer who accommodates himself to the extremes of Gross's and Frishberg's styles and helps fuse the trio into a cohesive and coherent group. I had to come and go during their three hours on the stand, but heard their performances of Thelonious Monk's "Ask Me Now;" Gary McFarland's "Blue Hodge;" Bob Brookmeyer's "Dirty Man;" and three Ellington pieces, "Dancers in Love," "Strange Feeling" and "Scronch." Some of those are on their only CD, which I have recommended before and recommend again. It was a pleasure to hear them in person.

who made his mark in the most avant garde band Shelly Manne ever had, is a tenor saxophonist who calmly and with a rich tone plays iconoclastic ideas. Frishberg is a celebrated performer of his own songs whose policy is never to sing in Portland, his home town. He does, however, accept gigs there as a pianist. He is one of the best pianists in the mainstream. Doggett is a young drummer who accommodates himself to the extremes of Gross's and Frishberg's styles and helps fuse the trio into a cohesive and coherent group. I had to come and go during their three hours on the stand, but heard their performances of Thelonious Monk's "Ask Me Now;" Gary McFarland's "Blue Hodge;" Bob Brookmeyer's "Dirty Man;" and three Ellington pieces, "Dancers in Love," "Strange Feeling" and "Scronch." Some of those are on their only CD, which I have recommended before and recommend again. It was a pleasure to hear them in person.

That's enough for now. In the third and final installment of this Portland report, I'll give you a few words on McCoy Tyner, Don Byron and Lionel Loueke.

What to add to the hundreds of tributes to Louie Bellson in the wake of his death last weekend? The outpouring of accolades emphasizes what anyone who ever encountered him knows: he was full of warmth, generosity and the largest available portion of human spirit. Dozens of obituaries are quoting Duke Ellington's assessment of Bellson as not only the world's greatest drummer but the world's greatest musician. There are excellent obits by Howard Reich in the Chicago Tribune, Nate Chinen in The New York Times and Don Heckman in The Los Angeles Times.

What to add to the hundreds of tributes to Louie Bellson in the wake of his death last weekend? The outpouring of accolades emphasizes what anyone who ever encountered him knows: he was full of warmth, generosity and the largest available portion of human spirit. Dozens of obituaries are quoting Duke Ellington's assessment of Bellson as not only the world's greatest drummer but the world's greatest musician. There are excellent obits by Howard Reich in the Chicago Tribune, Nate Chinen in The New York Times and Don Heckman in The Los Angeles Times.

The grins on the faces of Hinton and Bellson when Earl Hines was in full flight.

Despite difficult economic times, Royston (pictured) said, overall attendance at the two-week

festival so far has been down only twelve percent compared with the 2008 festival. Tickets for the Wilson-Moran concert lagged despite Ms. Wilson having won a Grammy award last week. Royston said that other weekend concerts will go on. Among the headliners are Bobby Hutcherson, Lou Donaldson, Aaron Parks, Pat Martino, Jane Bunnett and Kurt Elling.

festival so far has been down only twelve percent compared with the 2008 festival. Tickets for the Wilson-Moran concert lagged despite Ms. Wilson having won a Grammy award last week. Royston said that other weekend concerts will go on. Among the headliners are Bobby Hutcherson, Lou Donaldson, Aaron Parks, Pat Martino, Jane Bunnett and Kurt Elling.Last weekend, it seemed that, except for a few empty rows in the backs of the halls, the concerts were well attended. Portland's weather, which can be rainy at this time of year, was cold and dry, making for exhilarating trips through downtown between concert halls, clubs and restaurants. Since I last attended the Portland festival in 2007, it has made a significant improvement in the way it presents music. The prime-time evening concerts now take place not in hotel ballrooms with boomy acoustics and frustrating sight lines, but in performance halls designed for satisfying aural and visual experiences.

"We've grown in that regard," Royston told me. "It was time." Most of the concerts were in the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, home of the Oregon Symphony, or in the auditorium of the Portland Art Museum. One exception to the no-hotel policy was a concert in the Pavilion Ballroom of the Portland Hilton. In the gargantuan ballroom in the hotel's nether regions in previous years, performances were all but unlistenable. The Pavilion is a cozier hall with good acoustics and a lovely little stage.

Before I give you brief impressions of what I heard, I must observe that the festival's eye-catching logo should do wonders for the hairdessing and soprano saxophone industries.

In recognition of Blue Note Records' 70th anniversary, the festival was heavily populated by musicians signed to that label, with Blue Note president Bruce Lundvall and executive producer Michael Cuscuna avuncular presences through most of the weekend. Cuscuna was on several panels. Introducing one concert, he said, "My voice is going. They've had me talking since I got off the plane two days ago."

My first event was an hour chatting with Joe Lovano and an audience. Lovano might be described as the festival's house saxophonist. In an introduction, Royston called him ubiquitous. As articulate and interesting talking about music as he is playing it, Lovano participated in four concerts and two extended gabfests, in addition to unofficial and

entertaining after-hours discussions at the bar. At the art museum, he unveiled a new group called Joe Lovano Us 5, previewing Folk Art, the CD they will release in May.

entertaining after-hours discussions at the bar. At the art museum, he unveiled a new group called Joe Lovano Us 5, previewing Folk Art, the CD they will release in May.

With a wireless microphone on his horn, roaming the stage, bear dancing, conducting with body language, Lovano was riveting to hear and fascinating to watch. The band had James Weidman at the piano, Michael Formanek on bass, and two drummers, Francesco Mela and Gerry Hemingway. Lovano was the star, but inventive interaction among all hands was the rule. The drummers did not engage in battles, but traded the primary percussion role and had drum conversations in which listening was as crucial as reacting. With Hemingway and Mela, it was a cooperative venture in rhythm and mutual appreciation, the opposite of one-upmanship. The same principle applied in interchanges between Lovano and the drummers, between Formanek and Lovano, between Weidman and the drummers. The pieces, all Lovano compositions, were mostly new but also included the ballad "The Dawn of Time," recorded on his Symphonica and Universal Language CDs. Here, it took on new levels of abstraction.

The interaction continued and intensified when Lovano's wife Judi Silvano sat in. A vocalist of

astonishing range, control and accuracy, she and her husband improvised melodic lines in unison, paralleling one another with timing tighter than split-second. Two nights later, in her own concert, Silvano sang with Lovano, Formanek and Hemingway as her sidemen. A dancer, Silvano uses gestures, eye movement, turns of the head and subtleties of shoulder motion as she does wordless singing that seems like speech, captivating audiences for whom music so experimental and daring might otherwise be mystifying.

astonishing range, control and accuracy, she and her husband improvised melodic lines in unison, paralleling one another with timing tighter than split-second. Two nights later, in her own concert, Silvano sang with Lovano, Formanek and Hemingway as her sidemen. A dancer, Silvano uses gestures, eye movement, turns of the head and subtleties of shoulder motion as she does wordless singing that seems like speech, captivating audiences for whom music so experimental and daring might otherwise be mystifying.

Preceding Lovano at the Friday night concert were pianist Jacky Terrasson and his trio. Terrasson played a succession of pieces in which the hard edge of his technique

ruled. For all of his considerable harmonic knowledge, the piano under Terrasson's hands was primarily a percussion instrument. Even an original ballad with melodic touches suggesting "Skylark" developed into an exhibition of keyboard power. Toward the end of his set, he reverted to subtlety in the development of a calypso piece that had harmonic suggestions of Sonny Rollins's "St. Thomas." Building on astringent harmonies, Terrasson constructed a towering edifice of sound. As he shifted back down, it turned out that the piece had indeed been "St. Thomas" all along. He simply chose to withhold its identity until the end, a surprise the audience accepted with enthusiasm.

One evening following a concert, I walked twenty blocks or so to the Pearl District, where drummer John Bishop, guitarist John Stowell and bassist Jeff Johnson were playing at the Rogue Pub. I found them in a corner with their backs to plate glass windows on two sides, playing to a packed house of Portlanders in a mood to celebrate, drinking lots of Rogue ale. About six of the patrons were listening through the loud conversations of the other hundred or so. Stowell, who is capable of the greatest refinement in his playing, cranked up his amp, Johnson and Bishop adjusted their volumes accordingly, and the trio known as Scenes wailed. All of the tunes I heard them do, with the exception of "Solar," were original compositions by members of the band and all of them were intriguing. During a break, I asked Bishop how he liked working under those conditions. "Great," he said. "it's a gig." They are easier to hear on their CD, which also includes tenor saxophonist Rick Mandyck.ore on the Portland festival in the next post.

We gathered at the hotel Thursday night. Chuck flew in from Florida to conduct and play a concert with the Buffalo Philharmonic. Janet and I drove in so that we could have a Valentine's dinner that night and so that I could play and solo in the concert on Friday. Kevin Axt (bass player) and Dave Tull (drummer) flew in from LA via Philadelphia (with a dicey landing in Phila.) and lead trumpet Jeff Kievit, who handles Chuck's orchestra library, drove up from New Jersey so that he wouldn't have to deal with carrying all the cases of music books on a plane -- the one the others were on.

Kevin, Dave, Jeff, Janet and I met in the lobby and were excited, happily anticipating the fun of doing an orchestral concert with all its challenges and opportunities.

But a very joyful evening turned horrifically tragic in a way of which nightmares are made...

Although Gerry Niewood usually played and recorded with Chuck, he played on my last three CDs and had great solos on all of them. He also has played concerts with my big band in Rochester and Buffalo. We've played together in a variety of settings and formats, mostly with Chuck, for more than four decades.

Gerry Niewood Coleman Mellett

Coleman Mellett had a way of playing extremely difficult music of all genres and styles, with creativity and capability well beyond his 33 years. It was truly a joyful musical treat to be next to him on stage as we were for the 2007 Friends and Love concert at the Eastman Theater (with Gerry) and the November 2008 pair of concerts with the Syracuse Symphony. We would groove off of one another, reaching for things musically, and nodding and smiling when we got there.

The world lost two most wonderful people and two magnificent musicians.

Three days of music are echoing in my head. My notebook is full. As I drive through the gorgeous Columbia River Gorge on the way back to Rifftides World Headquarters, I'll be thinking about how to boil down hours and hours of listening into a cogent report or two. For now, suffice it to tell you that the Portland Jazz Festival, saved more or less at the last moment from extinction, rallied, is a success and has matured into one of the finest jazz festivals in the world. As I motor along, I may be a bit distracted by scenery like this.

In the next day or two, I will also post thoughts about drummer, composer, band leader and mensch Louie Bellson, who died on Saturday.

In the next day or two, I will also post thoughts about drummer, composer, band leader and mensch Louie Bellson, who died on Saturday.

(Portland, Oregon) - At the Portland Jazz Festival between concerts and after hours, much of the talk among musicians is about the death of Gerry Niewood. The saxophonist was one of 50 people who died in a plane crash Thursday night near Buffalo, New York. He and guitarist Coleman Mellett were on their way to Buffalo to perform with Chuck Mangione's band. Mellett was also killed in the crash.

Niewood was a childhood friend of Mangione. He and the trumpeter played together in youth bands and became even closer musically at the Eastman School of Music in their native Rochester. Niewood was not on the celebrated Mangione Feels So Good album, but his association with Mangione's huge success brought him attention and admiration among fellow musicians. That never translated into wide popular acceptance after he became a leader of his own group. He developed a successful career as a free-lancer on several reed and woodwind instruments and through the years rejoined Mangione for tours and in concerts recreating what became known as their Friends and Love music, which has retained popularity through four decades.

Niewood was a childhood friend of Mangione. He and the trumpeter played together in youth bands and became even closer musically at the Eastman School of Music in their native Rochester. Niewood was not on the celebrated Mangione Feels So Good album, but his association with Mangione's huge success brought him attention and admiration among fellow musicians. That never translated into wide popular acceptance after he became a leader of his own group. He developed a successful career as a free-lancer on several reed and woodwind instruments and through the years rejoined Mangione for tours and in concerts recreating what became known as their Friends and Love music, which has retained popularity through four decades.

Respected for his technique and solid tonal qualities on all of his instruments, Niewood said in a 2006 interview with Rochester's City Newspaper, "I don't start to play until I hear something that I want to play. I try to develop it and have that thread of continuity. I'm not big on the use of pyrotechnics. I'm a melodic player, a rhythmic player, a harmonic player. I'm not a flashy player."

In Portland, a group of musicians and friends who knew Niewood stood at the Arts Bar of the Portland Center for the Performing Arts listening to the John Gross Trio with Dave Frishberg and Charlie Doggett. Between tunes, much of the talk was about Niewood. Joe Lovano was particularly warm in his admiration for his fellow saxophonist's musicianship. Judy Cites, the tour manager for Mangione's band when Niewood was a member, recalled him as one of the most natural and unaffected people she has known.

From Rochester, a longtime friend of Niewood adds a memory from their early careers. The friend is Ned Corman, head of a national organization called The Commission Project, which is devoted to jazz education for children from grade school through college age. In his days as a saxophonist, Mr. Corman worked with Niewood and the Mangione brothers.

Some of the best music I was part of was a ten-piece band Chuck Mangione led in the late 60's. Chuck and Sam Noto were the trumpet section. I don't remember the trombone section. Gap Mangione, Frank Pullara and Vinnie Ruggerio were the rhythm section. Gerry, Joe Romano and I were the saxophone section. Gerry was also part of the FRIENDS AND LOVE concert, perhaps the only time I was fortunate to make music with Marvin Stamm. A piece of information little known beyond Penfield High School music students: Gerry did his student teaching at PHS and Denonville Middle School. Students took lots of pride that Gerry was their teacher as well as a star with Chuck Mangione.

Gerry Niewood was 65. For an obituary, go here.

Addendum, February 16: For an interesting insight into Niewood's and Mellett's lives as itinerant musicians, see Nate Schweber's piece in today's New York Times.

lived there for three years long ago when my television news career was getting into gear -- the second-gear phase, I suppose. The occasion is the first weekend of the Portland Jazz Festival, rescued from the budget shortfall that canceled it for a time. For details of the bailout go here. It has nothing to do with the Obama stimulus plan. For the festival lineup, go here.

lived there for three years long ago when my television news career was getting into gear -- the second-gear phase, I suppose. The occasion is the first weekend of the Portland Jazz Festival, rescued from the budget shortfall that canceled it for a time. For details of the bailout go here. It has nothing to do with the Obama stimulus plan. For the festival lineup, go here.

I'm reading the Rifftides discussion about Blossom Dearie and Bill Evans, and who influenced who. I'd like to add my comment: During the late sixties I played a couple weeks solo opposite the Bill Evans Trio at the Village Gate on Bleecker St, and had some conversations with Bill. I asked him how he came upon his piled-fourths voicing of chords, and his immediate answer was that he heard Blossom Dearie play that way and it really knocked him out. Then he did a little rave review of Blossom, naming her as one of his models of piano playing. It was such a surprising response that I never forgot it.

A decade or so later Blossom and I were doing a two-piano act, and I got to see what he was talking about. Blossom showed me some voicings she was using, and then I sat down at the same piano and tried them out but it didn't sound like Blossom. I told her, "It sounds better when you do it." She said, "Oh well, I know this piano, I'm used to it." The truth is she seemed to get her special sound out of any piano. Also, she could play softer than anyone I ever heard. The accompaniment she gave herself was all carefully composed, and she played it note for note every night. Why not? It was perfect.

When Blossom Dearie died at 82 over the weekend, we lost a brilliant musician whose subtle artistry and private nature conspired to limit her popularity. There was nothing about her "teacup voice," as Whitney Balliett described it, or her sophisticated harmonic sense at the piano that could have led to mass adoration. Nonetheless, for decades she was idolized by a substantial base of listeners charmed by her singing and of musicians who admired her integration of vocal performance with self-accompaniment. No singer has been better at playing for herself.

When Blossom Dearie died at 82 over the weekend, we lost a brilliant musician whose subtle artistry and private nature conspired to limit her popularity. There was nothing about her "teacup voice," as Whitney Balliett described it, or her sophisticated harmonic sense at the piano that could have led to mass adoration. Nonetheless, for decades she was idolized by a substantial base of listeners charmed by her singing and of musicians who admired her integration of vocal performance with self-accompaniment. No singer has been better at playing for herself. Blossom's piano playing was probably influenced a lot by Ellis Larkins. She voiced like he did, and had that same delicate touch. Bill Evans' early playing reflected a lot of Lennie Tristano... I'm sure he must have heard Blossom when she was around the Village, but I think he worked his ideas out pretty much by himself.

Count

Basie, Oscar Peterson, Niels-Henning Ørsted-Pedersen, Martin Drew

My, what a standard of perfection is now demanded. No longer is a good or even a great performance good enough. Now we must have performances free from the "slightest glitch." And since no one -- not even a singer of Ms. Hudson's manifest talent nor a violinist of Mr. Perlman's virtuosity -- can guarantee that a live performance will be 100% glitch-free, the solution has been to eliminate the live part. Once, synching to a recorded track was the refuge of the mediocre and inept; now it's a practice taken up by even the best artists.

Whatever the motivation, the fear of risking mistakes has led musicians to deny who they are as performers. The most disheartening thing about the Inauguration Day quartet's nonperformance was the lengths to which they went to make sure that nothing they did on the platform could be heard. Cellist Yo-Yo Ma put soap on the hair of his bow so that it would slip across the strings without creating even a wisp of sound. The inner workings of the piano were disassembled. There is something pitiful and pitiable about musicians hobbling their own voices.

You get that right-tickin' rhythm, man, and it's ON!

So easy, when you know how.

One never knows, do one?

And here's another frequently used term that has no meaning whatsoever: "Hard Bop". I have NO IDEA what that MEANS (as opposed to supposed to mean).

The urge to put ideas in boxes will not be denied. Accordingly, one day in the early 1950s someone, presumably a critic, dreamed up a box called "hard bop." The inventor no doubt intended the term to be a synonym for "soul" and "funk." He or she may also have meant it to distinguish jazz played primarily by black people on the East Coast from jazz played primarily by white people on the West Coast. It seemed important to critics in those days to make that distinction. To some, it still seems important. At any rate, "hard bop" came to signify jazz that had rhythmic drive, leaned on blues harmonies, drew inspiration from church gospel music and was hot, not cool.

Unfortunately for box theory, try as you will to contain music, it flows around, into and out of boxes. Strict hard bop constructionists cannot force this album's lyrical "I Married An Angel" into the category with any greater justification than they can jawbone Clifford Brown's "Daahoud" (the Pacific Jazz version) into the shape of West Coast Jazz. Nearly half a century later, the music in this collection swings on in the category that matters most: the one labeled "Good."

The notes then discuss the musicians and the 21 tracks on the CDs.

...So it is quite possible that there never really was a musical style that could properly be described a "hard bop." However as Doug's not quite tongue-in-cheek essay reminds us, there was a powerful music developing in the mid-fifties. I lived and worked in the New York area during that time span, so I was thoroughly immersed in it throughout its early development. I know that I continue to think of this music as "hard bop" whenever I think back on it (which is often), and when I heard it still being played by many of today's best young jazz people, which is also quite frequently.

...I join Doug Ramsey in not giving a damn about the legitimacy of the terminology, because what really matters is that the music itself was among the most legitimate and exciting jazz ever created. - O.K.

about eighteen. Irwin's compositions and arrangements have a concomitant freshness about them, and resourcefulness. His writing tends to make his quintet sound bigger. There is no piano; Ben Monder's guitar has the chording assignment. Chris Cheek's tenor sax adds a third melody voice. Both solo with economy and plenty of unexpected turns, as does Irwin. Matt Clohesy is the bassist, Ferenc Nemeth the drummer.

about eighteen. Irwin's compositions and arrangements have a concomitant freshness about them, and resourcefulness. His writing tends to make his quintet sound bigger. There is no piano; Ben Monder's guitar has the chording assignment. Chris Cheek's tenor sax adds a third melody voice. Both solo with economy and plenty of unexpected turns, as does Irwin. Matt Clohesy is the bassist, Ferenc Nemeth the drummer.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary