main: April 2008 Archives

Emil Viklický, Ballads And More (ARTA).

Writing the other day about František Uhlíř triggered a search through recently arrived CDs for

the latest collection by Emil Viklický's trio. Viklický is the pianist in whose group Uhlíř has long been the bassist. He has collaborated with his contemporary George Mraz, another virtuoso Czech bassist, on two albums combining their beloved Moravian folk music with the jazz forms of which they are masters.

the latest collection by Emil Viklický's trio. Viklický is the pianist in whose group Uhlíř has long been the bassist. He has collaborated with his contemporary George Mraz, another virtuoso Czech bassist, on two albums combining their beloved Moravian folk music with the jazz forms of which they are masters.

I have been listening to Ballads And More all day and marveling at Viklický's ability to fold into his thoroughly modern jazz conception the sensibility that originates in his Moravian heritage and is fed in great part by his adoration of the Czech national hero Leos Janáček. Viklický injects a suggestion of minor-key Moravian reflection even into major-key standards like "I Fall In Love Too Easily" and "Polka Dots And Moonbeams. There is much more than a suggestion in his own "Highlands, Lowlands." The program includes pieces by Cole Porter, Richie Beirach, Keith Jarrett, Harold Arlen and Pat Metheny (the touching "Always and Forever"). Jimmy Rowles's "Peacocks" follows Billy Strayhorn's "A Flower Is A Lovesome Thing," songs so suited to one another that I'm surprised musicians don't regularly pair them.

Uhlíř is brilliant throughout. European bassists trained in the academy tend to have flawless command of the bow. Uhlíř's arco solo on "Peacocks" is a stunning example. Drummer Laco Tropp's melodic mallets solo on Sammy Cahn's and Saul Chaplin's seldom-played "Dedicated To You" leads into a Viklický solo in which for a few bars his dazzling technique gleams through the ballad relaxation. Tropp evidently doesn't have an exhibitionist bone in his body. He settles for playing great time.

If your neighborhood is one of the few that still has a record store, Ballads And More may not show up in it. The Czech company ARTA's physical distribution is not world-wide. The internet, so far, is.

If you'd like to see Viklický, Uhlíř and Tropp in action, go here.

Jimmy Giuffre could play the tenor saxophone with a rhythm and blues raucousness that

reflected his Texas origins. For a time in the 1950s, though, the low-register intimacy of his clarinet was one of the most identifiable sounds in jazz. Giuffre died last Thursday of complications from the Parkinsons disease that for years had limited his activity in music.

reflected his Texas origins. For a time in the 1950s, though, the low-register intimacy of his clarinet was one of the most identifiable sounds in jazz. Giuffre died last Thursday of complications from the Parkinsons disease that for years had limited his activity in music.

Featuring Jim Hall's guitar and Ralph Peňa's bass or Bob Brookmeyer's valve trombone, he rooted his trio in blues, folk music and standard songs. In this video clip from the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958, Giuffre plays tenor saxophone. In the early 1960s, Giuffre morphed his group into a risk-taking trio of adventurers. With pianist Paul Bley and bassist Steve Swallow he explored the expanding harmonic and expressive boundaries of free jazz, in the process taking his clarinet into the stratosphere as well as the basement of its range.

A gifted composer from his college days onward, Giuffre was a major contributor to the Third Stream music that aimed to forge a synthesis between jazz and classical forms. But for all his inventiveness, hard work and dedication, for all the admiration and respect he earned well into the 1990s, a Giuffre work from early in his career is his most recognizable monument.

That piece, of course, is "Four Brothers," a 1947 hit for Woody Herman's Second Herd and a staple in the repertoires of big bands ever since. The arrangement featured Stan Getz, Zoot Sims Herbie Steward and Serge Chaloff -- and the legion of saxophonists who have followed them in several subsequent Herds. Herman died twenty-one years ago, but the arrangement is a part of every appearance by the band that still tours under his name. Click here for a performance of "Four Brothers" by one of the last editions of the band with Herman at the helm.

It might have been a source of both amusement and satisfaction to Giuffre if, before he died, he saw affirmation that his composition was officially enshrined in American popular culture when it was played on the sidewalks of Disneyland by Mickey's Toontown Tuners. And I hope that he knew about this version from Hungary, but definitely not from hunger, by a pair of violinists and an impressive big band. "Four Brothers" long ago went global.

Jimmy Giuffre, 1921-2008.

From time to time Rifftides Washington, DC correspondent John Birchard favors us with reviews of musical events in his bailiwick. Here is his latest.

JAZZ AT VOA

Willis Conover Memorial Concert with a Tribute to Quincy Jones

April 26, 2008

Review by John Birchard

Quincy Jones is an icon, a legend. Heavy-laden with honorary doctorates, awards, Grammys (27 of them), Kennedy Center Honors, he is lauded for his work with Frank Sinatra, Barbara Streisand and Michael Jackson. Almost lost in the mists of time is the

reason Jones came to the attention of such artists: his enormous talent for composing and arranging for a big jazz band.

Last night, at the Voice of America auditorium in Washington, DC, those compositions and arrangements were brought back to life in a concert dedicated to the memory of VOA's long-time host of jazz programs, Willis Conover. The Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, under the direction of David Baker, presented a program of Quincy Jones charts that was - to borrow Mr. Jones's middle name - a Delight.

I'm not a particularly big fan of jazz repertory bands and recreation of the hits of the past. But there are exceptions and this night was one of them. The program began with "Pleasingly Plump", a medium-tempoed swinger that contains the essential elements of Jones's work: a relatively simplicity in the writing, an attractive melody voiced in harmonies that are still fresh as the day they poured from his pen and a momentum that flows from beginning to end. It was obvious to this observer that the members of the SJMO were enjoying themselves with Jones's music.

The band was crisp, well-rehearsed and the soloists were fired up. During the course of the evening, effective contributions came from trumpeters Tom Williams and Kenny Rittenhouse, trombonist Bill Holmes, saxophonists Scott Silbert, Charlie Young and Lyle Link, and the rhythm section of pianist Tony Nalker, bassist James King and drummer Ken Kimery.

The only non-Jones chart - Lester Young's "Tickle Toe" - was arranged by Al Cohn, so there was no sag in quality. The rest of the night was devoted to Jones' memorable sounds - "Jessica's Day", "Soul Bossa Nova" with piquant piccolo work from Scott Silbert and Charlie Young, and "The Quintessence" featuring a passionate solo from lead alto player Young, in a piece made memorable by another alto man, Phil Woods, back in the day.

The Smithsonian band performed at a high level throughout, but the highlight for this listener was its reading of "The Witching Hour", which brought cheers from the audience. Jones's chart is a model of big band writing, rich in harmonies, building through chorus after chorus and providing an inspirational setting for the soloists.

Other choice moments included the lovely ballad "Grace", and Jones' arrangements on Bobby Timmons' "Moanin'", the blues "Walkin'" and the swing era anthem "Air Mail Special" to wrap up a special evening. Somewhere, Willis Conover was smiling.

You may have heard but not seen František Uhlíř, the Czech bassist who works in the Emil Viklický Trio. The Rifftides staff is anticipating a copy of a new recording by Uhlíř's own trio, a group he has been touring with for five years. In the meantime, video of the Uhlíř trio has shown up on YouTube. The band includes Jaromir Helesic on drums and Darko Jurkovic, one of the few guitarists who plays the instrument by tapping it with the fingers of both hands. The video was made in the historic Knoxoleum in Burghausen, Germany. This is an opportunity for those of us outside Europe to withess in action one of the world's great bassists--and an intriguing guitarist whose easy execution belies the intensity of his music. Click here for their performance of "Maybe Later."

![]() The National Public Radio Jazz Profiles program about Zoot Sims is now up on NPR's web site in streaming audio.

The show produced by Paul Conley and hosted by Nancy Wilson includes memories of the great saxophonist by Bob Brookmeyer, Dave Frishberg, Bill Holman, Harry Allen, Bucky Pizzarelli, Zoot's wife Louise and me. It also has plenty of music. To hear it, go here and click on "Listen Now."

The National Public Radio Jazz Profiles program about Zoot Sims is now up on NPR's web site in streaming audio.

The show produced by Paul Conley and hosted by Nancy Wilson includes memories of the great saxophonist by Bob Brookmeyer, Dave Frishberg, Bill Holman, Harry Allen, Bucky Pizzarelli, Zoot's wife Louise and me. It also has plenty of music. To hear it, go here and click on "Listen Now."

For a recent Rifftides piece on Sims and his tenor sax companion Al Cohn, go here. It includes a link to a performance video.

Rifftides reader Nina Ramos listened to Carol Sloane's newest recording, encountered something that disturbed her, and sent this message:

Just finished reading your liner notes and listening to Carol Sloane's Dearest Duke. I liked it very much - except - (and am I the only one to notice?) the extremely loud breathiness in the sax part of two pieces especially - "In My Solitude" and "I Got It Bad". It just about ruins both of those songs for me. Did I get a defective recording, or is that how it's "supposed" to sound?

Is he too close to the mike on these pieces? You didn't mention this in your liner notes so I wondered if your copy had the same loud breaths on it. Both of these sax solos start about 2 minutes into each song. As you can probably tell, I know very little about jazz, other than I like something or I don't. I loved her voice - but that sax.... Thank you for any information you care to give.

Dear Ms. Ramos,

Ken Peplowski (l), who got your attention in his collaboration with Carol Sloane, is paying homage to Ben Webster (r) (1909-1973), the great Duke

Ken Peplowski (l), who got your attention in his collaboration with Carol Sloane, is paying homage to Ben Webster (r) (1909-1973), the great Duke

Ellington tenor saxophonist. Webster's use of breathy vibrato on ballads was a trademark and, to many listeners, one of his most endearing qualities. Whether Peplowski was miked too closely is a matter of preference, I suppose, but there is no doubt that he was emulating Webster.

Ellington tenor saxophonist. Webster's use of breathy vibrato on ballads was a trademark and, to many listeners, one of his most endearing qualities. Whether Peplowski was miked too closely is a matter of preference, I suppose, but there is no doubt that he was emulating Webster.

The great Ellington band of 1940 and 1941 is generally identified in Ellingtonia as the Blanton-Webster band after two of its stars, bassist Jimmy Blanton and Ben Webster. This box set contains lots of classic Webster with Ellington in that period. This encounter with Gerry Mulligan has superb latterday Webster.

There is more information in the chapter on Webster in my book Jazz Matters: Reflections On The Music And Some Of Its Makers. Here's a paragraph.

In the beginning his playing was modeled closely on the dramatic, sweeping, even grandiose, style of Coleman Hawkins. But over time, Webster pared away embellishments and rococo elements while maintaining warmth and a big tone, and created a style that appeals with force and clarity directly to the emotions.If you seek out Webster's recordings, perhaps you, too, will submit to his charms. To see and hear him play "Old Folks" with Teddy Wilson on piano, click here. Yes, that's a tear rolling down Ben's cheek when Wilson finishes his solo. He felt things deeply.

In his new blog Jazz Profiles, Steve Cerrra is running a multi-part series on the late pianist Michel Petrucciani. In the current installment, Cerra discusses how during his period with Blue Note Records, Petrucciani dealt with his Bill Evans influence:

To hear a very specific example of this stylistic transition in the making, compare Michel's scorching treatment of "Night and Day", in which he puts on a dazzling display of "pianism," with the searching and tentative version offered by Evans of this song on the Everybody Digs Bill Evans, his second date for Riverside.

Of course, Evans was still in the process of discovering his systems of voicings on his version of the Cole Porter classic whereas Michel comes to this system 30 years later with it available as a fully developed basis for harmonic substitutions while playing this tune. Nevertheless, more and more, throughout "The Blue Note Years," one can discern the advent of Michel's unique Jazz voice.

To read the whole thing, go here.

Cerra has initiated an occasional series on, of all peculiar topics, jazz critics. He began it with a lovely piece about Whitney Balliett. Now, arriving at desperation early in the game, he has resorted to a sidebar about the proprietor of Rifftides. I am mystified and flattered.

You Molly") and assorted other ingredients. Think of gumbo. Ellis plays soprano saxophone and bass clarinet, but his individuality shines most brightly on tenor saxophone. His superb support troops are organist and accordianist Gary Versace, drummer Jason Marsalis and sousaphone virtuoso Matt Perrine. Yes -- sousaphone. You see one, greatly reduced, to your right. This album was recorded in Brooklyn, but it feels like a visit to Ellis's home town, New Orleans. Great fun.

You Molly") and assorted other ingredients. Think of gumbo. Ellis plays soprano saxophone and bass clarinet, but his individuality shines most brightly on tenor saxophone. His superb support troops are organist and accordianist Gary Versace, drummer Jason Marsalis and sousaphone virtuoso Matt Perrine. Yes -- sousaphone. You see one, greatly reduced, to your right. This album was recorded in Brooklyn, but it feels like a visit to Ellis's home town, New Orleans. Great fun.

Italian trumpeter Fresu, the French accordianist Galliano and the Swedish pianist Lundgren (l. to r.) blend in a program of their own compositions and one each by Jobim, Trenet and Ravel. The name of Lundgren's title piece translates as "Our Sea." That opening tune introduces an aura of reflection that never dissipates even through the relative liveliness of Fresu's "Years Ahead" and Galliano's "Para Jobim" or the compellingly familiar melodies of Ravel's "Ma Mere L'Oye. The tonal qualities of the three musicians are so distinctive, their harmonic resources so rich and melodic gifts so powerful that there is substance throughout. This is satisfying music with a long shelf life.

Italian trumpeter Fresu, the French accordianist Galliano and the Swedish pianist Lundgren (l. to r.) blend in a program of their own compositions and one each by Jobim, Trenet and Ravel. The name of Lundgren's title piece translates as "Our Sea." That opening tune introduces an aura of reflection that never dissipates even through the relative liveliness of Fresu's "Years Ahead" and Galliano's "Para Jobim" or the compellingly familiar melodies of Ravel's "Ma Mere L'Oye. The tonal qualities of the three musicians are so distinctive, their harmonic resources so rich and melodic gifts so powerful that there is substance throughout. This is satisfying music with a long shelf life.

Hadley Caliman, Gratitude (Origin). I wrote in Jazz Matters about Caliman in a 1979 performance with Freddie Hubbard's band:

As the evening progressed, Caliman's playing took on much of the intensity and coloration of John Coltrane's work, but he is a more directly rhythmic player than Coltrane was toward the end of his life and from that standpoint is reminiscent of Dexter Gordon. Whatever his influences, Caliman is an inventive and cheerful soloist.

Caliman recently retired as a college music educator but not as a tenor saxophonist. He still

sounds cheerful and at least as inventive as during his heyday (he made his first records in Los Angeles in 1949 when he was seventeen and a student of Gordon). With Thomas Marriott on trumpet and a splendid rhythm section, Caliman has a Coltrane quotient on ballads like his lovely "Linda" and Kurt Weill's "This Is New." He employs plenty of Gordon's brand of incisiveness and swing on faster pieces including Joe Henderson's "If." Yet, there is no mistaking him for anyone but Hadley Caliman. Young Marriott, increasingly impressive for his fluency and capacious sound, is an ideal front line partner and contrasting soloist. Vibraharpist Joe Locke, bassist Phil Sparks and drummer Joe LaBarbera have fine solo moments and comprise a blue ribbon support team.

sounds cheerful and at least as inventive as during his heyday (he made his first records in Los Angeles in 1949 when he was seventeen and a student of Gordon). With Thomas Marriott on trumpet and a splendid rhythm section, Caliman has a Coltrane quotient on ballads like his lovely "Linda" and Kurt Weill's "This Is New." He employs plenty of Gordon's brand of incisiveness and swing on faster pieces including Joe Henderson's "If." Yet, there is no mistaking him for anyone but Hadley Caliman. Young Marriott, increasingly impressive for his fluency and capacious sound, is an ideal front line partner and contrasting soloist. Vibraharpist Joe Locke, bassist Phil Sparks and drummer Joe LaBarbera have fine solo moments and comprise a blue ribbon support team.

This CD is about fifty minutes long. I point that out in praise, not condemnation. The fact that a compact disc can run eighty minutes does not mean that it should. On Caliman's record, solos are thoughtful, to the point and memorable. They could have gone on longer, but they didn't need to. Could this be a trend? Let us hope so.

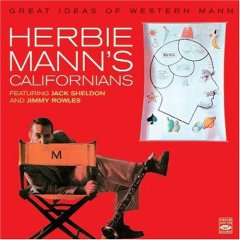

Herbie Mann's Californians, (Fresh Sound). This compilation reissue contains all of the Riverside album called Great Ideas Of Western Mann plus tracks from Riverside's Blues For Tomorrow and Verve's The Golden Flute Of Herbie Mann. In all cases, Jimmy Rowles is on piano, with Buddy Clark on bass and Mel Lewis on drums. For the rhythm section alone, this would be a desirable CD, but Mann's bass clarinet and Jack Sheldon's trumpet work on seven of the pieces make it an essential example of all hands' best work of the late 1950s. On the four remaining tracks, Mann plays flute with his customary jauntiness, but it's those bass clarinet solos and the instrument's blend with Sheldon's horn that stay in the mind. Mann's conception is hardly generic, but it is orthodox bebop. In Rowles and Sheldon, however, we hear two of the great eccentrics among improvisers of any era, departing from the trodden path and detonating little surprises.

Herbie Mann's Californians, (Fresh Sound). This compilation reissue contains all of the Riverside album called Great Ideas Of Western Mann plus tracks from Riverside's Blues For Tomorrow and Verve's The Golden Flute Of Herbie Mann. In all cases, Jimmy Rowles is on piano, with Buddy Clark on bass and Mel Lewis on drums. For the rhythm section alone, this would be a desirable CD, but Mann's bass clarinet and Jack Sheldon's trumpet work on seven of the pieces make it an essential example of all hands' best work of the late 1950s. On the four remaining tracks, Mann plays flute with his customary jauntiness, but it's those bass clarinet solos and the instrument's blend with Sheldon's horn that stay in the mind. Mann's conception is hardly generic, but it is orthodox bebop. In Rowles and Sheldon, however, we hear two of the great eccentrics among improvisers of any era, departing from the trodden path and detonating little surprises.

Music allows the great opportunity to play with people who turned you on and you love.

To most jazz critics I was basically Kenny G.

It turns out that rumors of the imminent death of the IAJE were accurate. Following its financially disastrous 2008 conference in Toronto, the International Association of Jazz Education has canceled its 2009 conference and is about to file for bankruptcy. The huge meeting of musicians, educators, producers, record company executives and others from every precinct of jazz was to have been held in Seattle next January.

The IAJE grew from a music educators' collective into a behemoth whose organizational weaknesses allowed it to topple of its own weight. For years, there have been grumblings among musicians, critics, bookers and producers that IAJE had gained too much power over careers and the business of jazz. Until Toronto, few knew of the fragility of the organization.

Be on the alert for attempts to fill the role of an outfit that, for all its faults, once a year brought together from around the world a substantial portion of the jazz community. Seattle Times music critic Paul deBarros, a veteran IAJE watcher, wrote in today's paper:

To read all of de Barros's article, click here.In a good year, the conference attracts 7,000 to 8,000 people, a must-attend for anyone involved in jazz.

Rumors that the organization was in trouble surfaced after this year's dramatically underattended conference in Toronto, down 40 percent.

Carol Sloane's individualism as a singer grows, in part, out of her adoration of Carmen McRae. In the confusion of the past week, I overlooked Sloane's tribute to McRae on what would have been Carmen's eighty-eighth birthday. Here is some of what she wrote:

When she laughed, the room vibrated; when she spewed venom, people, animals and birds hastily fled the scene.

Carol's assessment nails the yin and yang of the phenomenon that was Carmen McRae. To read all of her tribute to McRae and see the stately photograph she chose to accompany it, go here.

My own encounters with Carmen were few but unforgettable. The first was in 1956. Gus Mancuso and I were in San Francisco for his first recording session for Fantasy. We had just checked into a musicians' hotel in the Tenderloin, not far from the Blackhawk.

We were in the elevator on the way up to our floor. The car stopped and in walked a woman looking like this. She rode one floor and got out.

We were in the elevator on the way up to our floor. The car stopped and in walked a woman looking like this. She rode one floor and got out.

"My God," Gus said after the door closed, "that was Carmen McRae."

"Why didn't you say something to her?" I said.

"I couldn't," he told me. "I was speechless."

At the New Orleans Jazz Festival in 1968 or '69, I was assigned to introduce McRae at a concert. Before her set we spent a few moments chatting. After the concert, we socialized briefly with other people. Four years later, I had moved to New York. Late one night after I got off the air, I went up to Harlem where McRae was appearing at the Club Barron with her trio. I arrived as she was starting the last song of a set, went to the bar and ordered a drink. A couple of large men who were not quite sober looked me over, uttered comments that could not have been interpreted as words of warm greeting, and began edging closer.

The moment the song ended, Carmen walked briskly over to me and said, "We know each other, don't we. It's good to see you again." She aimed the power of her glare at the aggressive welcoming committee. "Let's have a seat," she said. We went to a table. Before the break ended, Dizzy Gillespie walked in, carrying his trumpet case. He joined us and when the next set started, Dizzy sat in with Carmen. It was an unforgettable collaboration.

When that set was over and it was time for me to go, Carmen asked one of the heavies who had started moving in on me to see that I got into a cab. He escorted me to the street, hailed a taxi and waited until the cab pulled away.

When I next saw Carmen, several years later, I said, "I owe you one." She smiled softly. And that was that.

The long computer nightmare and its peripheral bad dreams are over. Well, almost over. In the resurrection and reinstallation of the machine and the replacement of a connected printer/scanner/fax that blew out in the process, one of my two telephone lines crashed. That, however, is a small matter compared with relief that the hard drive lives. Not to have had backup was foolish. I was fortunate to survive what could have been a massive loss of files.

Hard drives are fragile, fickle, unpredictable creatures. If you don't have backup for yours, please get it. There are lots of options. My computer technician and savior recommended Simple Drive, a satellite hard drive made by a company called SimpleTech. Full disclosure: neither my tech nor I has stock, relatives or financial interest in the company.

Hard drives are fragile, fickle, unpredictable creatures. If you don't have backup for yours, please get it. There are lots of options. My computer technician and savior recommended Simple Drive, a satellite hard drive made by a company called SimpleTech. Full disclosure: neither my tech nor I has stock, relatives or financial interest in the company.

Tomorrow, onward and upward with never a backward glance at the recent unpleasantness.

To err is human, but to really foul things up requires a computer - Farmers Alamanac, 1978

The only thing God didn't do to Job was give him a computer - I.F. Stone

The Rifftides main computer crashed today. The ECTs (Emergency Computer Technicians) took it to the hospital for extensive tests. Results won't be known for at least three days. It may need a heart transplant and has no health insurance, but suggestions of a benefit concert are premature.

This message is coming to you by means of a Big Chief tablet and a number 3 pencil. The Rifftides Staff hopes to be back in full operation no later than Monday. Please be patient. In the meantime, we refer you to the archive. Click on "Archive" in the center column. There are all kinds of blasts from the past there. For starters, here's one of the earliest.

In his eighty-eighth year, Dave Brubeck is going to have to add another shelf to his trophy room--or another trophy room. His most recent honor came yesterday from the US State Department. Here's a paragraph from the Reuters report in The New York Times.

In his eighty-eighth year, Dave Brubeck is going to have to add another shelf to his trophy room--or another trophy room. His most recent honor came yesterday from the US State Department. Here's a paragraph from the Reuters report in The New York Times.

"As a little girl I grew up on the sounds of Dave Brubeck because my dad was your biggest fan," U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said at the ceremony where Brubeck received the department's Ben Franklin Award for public diplomacy.

To read the whole story, click here.

It is admirable that the State Department is honoring Brubeck for the valuable cultural diplomacy he and his quartet practiced with government sponsorship as recently as the 1980s. But what is the policy of The United States today in using culture to reach out to the world? Sad to report, official cultural diplomacy is largely dormant at a time when the country's international image is at its lowest point in decades. I recently delivered a speech entitled "Jazz Roots In The Bill Of Rights." Cultural diplomacy was not the main theme of the talk, but this paragraph touched on it.

Let us hope that the next administration will understand the importance and impact of what the USIA did--when there was a USIA--and revive the agency or create one like it.Not long after the Berlin Wall came down, the United States Information Agency asked me to go to Eastern Europe as part of its US Speakers program. That program no longer exists because the USIA no longer exists. The Clinton administration killed the agency in a budget move. The function shifted to the State Department and under the Bush administration, nothing has been done with it. Cultural diplomacy exists on paper, but it is not being practiced. That's a shame because there is intense interest in the world in how democracy and the concept of individual freedom work. We have laid aside a tremendously effective tool for making friends in the world by the simple, inexpensive means of sending Americans abroad to talk about America.

Have I mentioned that Dave Frishberg has a web site? He has. I am putting a link to it high on the Other Places list in the center column. The site has a discography, lots of photographs and a catalog of the songs he's written, from "Wallflower Lonely, Cornflower Blue" (1963) to "Who Do You Think You Are, Jack Dempsey?" (2004). It also has a Written Word section that includes a page called Colleagues And Characters, who include the unlikely--George Maharis, Scatman Crouthers, Malcolm X, Ava Gardner--and the likely, Carmen McRae, Benny Goodman, Kenny Davern, Ben Webster.

To reach Colleagues and Characters, click here, but take my advice: if you have an appointment soon or were thinking of getting some Z's, wait a while. Frishberg is hard to put down.

Ben was very emotional and his feelings were close to the surface. I knew that Ben was famous for unpredictable outbursts of anger and violence, but I never saw him pull any of those stunts,

perhaps because he was trying to abstain from hard liquor at that time. He did drink beer--Rheingold. When he drank he was quick to weep. He would ask Richard (Davis) to play solos with the bow, and then he would stand listening with tears rolling down his cheeks. He would get tearful when he spoke of his mother. Once he told me that he missed Jimmy Rowles, who was back in California, and as he told me about his friendship with Rowles he began to cry. One night at the Half Note we heard radio reports of rioting in Harlem, and Ben wept openly as he listened.

After he saw the Al and Zoot post (two exhibits down the page), the fine singer Bob Stewart suggested that we watch another video of Al Cohn performing with him. It captures a moment of spontaneity that creates a surprise and a big smile from Cohn. The rhythm section is Hank Jones, George Mraz and Ronnie Bedford. To see the clip, click here.

From the same engagement, Stewart sings "Caravan," which contains a typical Al Cohn solo: perfect.

--Billie Holiday, born on this date in 1915, died July 17, 1959

You can't copy anybody and end with anything. If you copy, it means you're working without any real feeling.

I hate straight singing. I have to change a tune to my own way of doing it. That's all I know.

Paul Desmond was fond of saying that an evening listening to Zoot Sims and Al Cohn at the old Half Note in downtown Manhattan was "like going to get your back scratched." There is a piece of video that helps explain what he meant. It's not from the Half Note, but from a 1968 British television program called In The Cool Of The Evening. They play Burt Bacharach's "What The World Needs Now," then a short version of Cohn's "Doodleoodle." The rhythm section is Stan Tracey, piano; Dave Green, bass; Phil Seamen, drums. To watch Al, Zoot and their British friends, click here.

Paul Desmond was fond of saying that an evening listening to Zoot Sims and Al Cohn at the old Half Note in downtown Manhattan was "like going to get your back scratched." There is a piece of video that helps explain what he meant. It's not from the Half Note, but from a 1968 British television program called In The Cool Of The Evening. They play Burt Bacharach's "What The World Needs Now," then a short version of Cohn's "Doodleoodle." The rhythm section is Stan Tracey, piano; Dave Green, bass; Phil Seamen, drums. To watch Al, Zoot and their British friends, click here.

There is lots of Sims on video but, evidently, very little of Cohn. An exception contributed by the singer Bob Stewart is his performance of "Laura" with Cohn sitting in. An anonymous YouTube commentator felt moved to remark on a rarity, Cohn making a mistake--but instantly recovering.

I actually enjoyed that clam at 2:04 where he plays the I-II-major III then quickly goes back and plays the I-II-minor III that fit in the chord.

To see and hear "Laura," click here.

The late pianist Lou Levy liked to tell of the time Stan Getz came off a solo with which he was particularly pleased, turned to Levy and said, "Who's your favorite tenor player now?"

"Al Cohn," Levy said. "Isn't he yours?"

And he was. Levy told me that when he visited Getz in his friend's final days, he usually found him listening to Cohn's recordings.

If you are too young or too old to be a part of the Muppets generation, you may have missed Zoot's alter-ego. Here's your chance to catch up.

Have a good weekend.

Allen Ganley, who died last week at the age of seventy-seven, was the preferred drummer not only of many of his fellow British musicians, but also of visiting Americans. He backed Stan Getz, Peggy Lee, Mary Lou Williams, Jim Hall, Art Farmer, Blossom Dearie, Roland Kirk and Freddie Hubbard, among many others.

Allen Ganley, who died last week at the age of seventy-seven, was the preferred drummer not only of many of his fellow British musicians, but also of visiting Americans. He backed Stan Getz, Peggy Lee, Mary Lou Williams, Jim Hall, Art Farmer, Blossom Dearie, Roland Kirk and Freddie Hubbard, among many others.

For years, Ganley was in the quintet and big band led by the volatile tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes. There is in this video clip from 1965 a prime instance of Ganley driving a band and soloing. The piece is "Killers of W1". (W1 is London's West End). The trumpeter is Jimmy Deuchar. In the same YouTube neighborhood you'll find several other clips of Ganley with Hayes. He is also prominent on the Hayes CD Tubbs.

For a review of Ganley's career, see his obituary from the Telegraph newspaper. The three men in the obit photograph are (l to r) Ganley, Victor Feldman and Ronnie Scott.

Gene Puerling, the leader and primary arranger for the Hi-Los, died March 25 in the San Francisco Bay area, where he had lived for decades. In his writing for the group, Puerling crafted complex arrangement that took them beyond anything previously heard from vocal quartets in American popular music.

Gene Puerling, the leader and primary arranger for the Hi-Los, died March 25 in the San Francisco Bay area, where he had lived for decades. In his writing for the group, Puerling crafted complex arrangement that took them beyond anything previously heard from vocal quartets in American popular music.

He formed the Hi-Lo's in 1953. Their source material came from the classic era of great American song writing, their harmonic inspiration from the riches of bebop, the perfection of their musicianship from studying Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Jo Stafford and vocal groups like the Modernaires and Mel Torme's

Mel-Tones. In the shadow of rock's burgeoning popularity, the group never hit the tops of the charts despite respectable sales for some of their best efforts, including the remarkable 1958 album The Hi-Lo's And All That Jazz, a masterpiece that is rapidly disappearing. Many of their other albums are still available on CD. Here's a paragraph about the Hi-Lo's from Puerling's obituary in The Los Angeles Times:

Mel-Tones. In the shadow of rock's burgeoning popularity, the group never hit the tops of the charts despite respectable sales for some of their best efforts, including the remarkable 1958 album The Hi-Lo's And All That Jazz, a masterpiece that is rapidly disappearing. Many of their other albums are still available on CD. Here's a paragraph about the Hi-Lo's from Puerling's obituary in The Los Angeles Times:

Their rich sound sprang from Puerling arrangements that could make other performers swoon. Jazz pianist and TV host Steve Allen is said to have called the Hi-Lo's "the best vocal group of all time." Singer Bing Crosby reportedly said: "These guys are so good they can whisper in harmony."

To read the Times obituary, go here.

Jon Hendricks, whose Lambert, Hendricks and Ross vocal group drew inspiration from the Hi-Los, is quoted in an article by Jesse Hamlin in today's San Francisco Chronicle.

"Gene broadened the harmonies, like Bird did with bebop," said Hendricks, comparing Mr. Puerling to pioneering saxophonist Charlie Parker. "The sound of the Hi-Lo's was choral, even though there were only four of them. The way the chords were spread out, they sounded like a choir."

To read all of Hamlin's piece, go here.

After the Hi-Lo's disbanded in 1964, Puerling founded The Singers Unlimited, arranged for groups including The Manhattan Transfer, and conducted vocal workshops. The Hi-Lo's reunited in 1970 for a performance at the Monterey Jazz Festival.

The charms and opportunities in bands of six to eleven pieces attracted jazz composers and arrangers eight decades ago, as they do to this day. For an overview and links to recordings of early mid-sized groups, go to the first installment of Medium But Well Done.

Separated by the width of the United States, in the second half of the 1940s two medium-sized bands working with different inspirations and source materials arrived at strikingly similar results. In New York, Miles Davis became the leader of a nine-piece band with arrangements by Gil Evans, Gerry Mulligan and John Lewis. In 1948, it wasn't called anything. Now, it's known as the Birth Of The Cool.

Davis and his confreres were interested in encapsulating the harmonic palette of the Claude Thornhill Orchestra for which Evans had created memorable arrangements. They wanted the freshness and improvisatory feel of Evans masterpieces for Thornhill like "Anthropology" and "Donna Lee." They were after more tonal subtlety and a less intense rhythmic approach than that of bebop, then in its heyday. In a typical bop performance, there was a group melodic statement, a succession of solos, and a repeat of the melody. In pieces by the Davis nonet, written and improvised sections of the music flowed together more or less seamlessly, without strain, in the vibratoless image of the Thornhill band. How well it succeeded in pieces like "Move," "Moon Dreams" and "Budo" is reflected in the enormous influence of the Birth Of The Cool band in the ensuing six decades.

Davis and his confreres were interested in encapsulating the harmonic palette of the Claude Thornhill Orchestra for which Evans had created memorable arrangements. They wanted the freshness and improvisatory feel of Evans masterpieces for Thornhill like "Anthropology" and "Donna Lee." They were after more tonal subtlety and a less intense rhythmic approach than that of bebop, then in its heyday. In a typical bop performance, there was a group melodic statement, a succession of solos, and a repeat of the melody. In pieces by the Davis nonet, written and improvised sections of the music flowed together more or less seamlessly, without strain, in the vibratoless image of the Thornhill band. How well it succeeded in pieces like "Move," "Moon Dreams" and "Budo" is reflected in the enormous influence of the Birth Of The Cool band in the ensuing six decades.

In northern California, Dave Brubeck and a few other chosen young men were studying at Mills College with the French modernist composer Darius Milhaud. As early as 1946, Brubeck, Dave Van Kriedt and Jack Weeks began working out solutions to problems raised in their studies in an ensemble they called, simply, The Eight. Later, it became the Dave Brubeck Octet.

Milhaud approved their efforts.

Milhaud approved their efforts.

"He liked our music," Brubeck told me. "He loved Kriedt's "Fugue on Bop Themes. " He said it was a wonderful example of a real fugue, written in a jazz style. He was as strict as could be about counterpoint. You had to follow his rules, which were Bach's rules. Kriedt just had a natural gift for writing fugues. How else could this young jazz player absorb that so fast and translate it into the jazz idiom? It's a classic piece." Here is more from the essay I wrote in 1992 for the retrospective Brubeck CD box Time Signatures.

There are interesting parallels between the Brubeck and Davis bands. Both were experimental, although in pieces like "Schizophrenic Scherzo" and "Rondo" the Brubeck Octet demonstrated more audacity with its polytonality and polyrhythms. Both bands were ahead of their time. Both had three paying jobs. On records made in the same year, 1949, both sound fresh and undated more than forty years later, still models for inventive uses of textures, counterpoint, moving harmonies and time signatures. (This remains true fifty-nine years later.) "Curtain Music" is in 6. Schizophrenic Scherzo and the bridge of "What Is This Thing Called Love" were in 7. Brubeck's adventures in time began long before "Blue Rondo a la Turk" and "Take Five."

There are similarities in phrasings of melody lines and in voicings, right down to the ways in which the alto leads of Paul Desmond and Lee Konitz were employed in the two bands. Classical influences and currents of musical thought in post-war jazz were informing composers and arrangers working 3000 miles apart. Gerry Mulligan, with Evans and John Lewis a key arranger for the Davis band, went on to form his own quartet, which became, like Brubeck's, one of the most successful of the 1950s.

In 1954, Mulligan formed a tentet modeled on the Birth Of The Cool Band and, later, put together his thirteen-piece Concert Jazz Band. The CJB, because of its size, was technically a big band, but in philosophy, spirit and execution it hewed to the principles he, Evans and Lewis developed with Davis in the late forties.

The gloriously testicular Chicago tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons led a succession of sextets more concerned with the basic emotions than with the refinements that occupied Davis and Brubeck. The arrangements were designed not to explore the possibilities of harmony or texture but to set off Ammons's heartfelt solos. They do that most effectively in "Pennies From Heaven," a witty pastiche of Christmas songs, the chugging "Jug Head Ramble" and a reduction of Ammons's "More Moon" feature from his days with Woody Herman. Those pieces and more from 1948 and '49 are in the fine reissue CD called Young Jug.

The gloriously testicular Chicago tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons led a succession of sextets more concerned with the basic emotions than with the refinements that occupied Davis and Brubeck. The arrangements were designed not to explore the possibilities of harmony or texture but to set off Ammons's heartfelt solos. They do that most effectively in "Pennies From Heaven," a witty pastiche of Christmas songs, the chugging "Jug Head Ramble" and a reduction of Ammons's "More Moon" feature from his days with Woody Herman. Those pieces and more from 1948 and '49 are in the fine reissue CD called Young Jug.

One arranger and leader whose work shows profound effects of the Birth Of The Cool recordings was an Ammons colleague from the Herman band, Shorty Rogers. At twenty-six, the trumpeter and arranger was also a veteran of the Red Norvo, and Stan Kenton bands. He took a nine-piece group into Capitol's Hollywood studio in 1951. The six pieces they recorded featured Art Pepper, Jimmy Giuffre, Shelly Manne, Milt Bernhart Hampton Hawes and

Rogers's writing full of zest and just enough complexity to be intriguing. "Popo," "Didi," "Four Mothers" and perhaps especially "Over The Rainbow" with its moving alto sax solo by Pepper get a large part of the credit--or blame--for establishing west coast jazz as a category, not just a geographic descriptor. It quickly became West Coast Jazz, typecasting that was good for commerce but stereotyped its musicians and has dogged them ever since.

Rogers's writing full of zest and just enough complexity to be intriguing. "Popo," "Didi," "Four Mothers" and perhaps especially "Over The Rainbow" with its moving alto sax solo by Pepper get a large part of the credit--or blame--for establishing west coast jazz as a category, not just a geographic descriptor. It quickly became West Coast Jazz, typecasting that was good for commerce but stereotyped its musicians and has dogged them ever since.

This CD includes those initial Rogers nonet tracks, along with the Mulligan Tentette pieces. This one, with the same musicians, has eight tracks recorded by Rogers and his Giants for Victor in 1953. Among them are the remarkable intertwining lines and swooping backgrounds of "Indian Club," "Diablo's Dance" with its great piano work by Hawes, and the amusing "Mambo del Crow," an early example of Rogers's effective use of Latin elements.

We haven't reached the mid-fifties, and there's much more to report in this survey of medium-sized bands. Next time--maybe even tomorrow--more from California with Don Faguerquist, Lennie Niehaus, Clifford Brown and Chet Baker. In the offing: Tadd Dameron, Al Cohn, Bob Brookmeyer, Bill Kirchner, Anthony Wilson, Bill Holman and Charles Mingus, among others.

Among the hundreds, possibly thousands, of spoofs appearing on the internet today is one in a column by Jack Bowers on the All About Jazz site.

Bowers nicely carries off the April Foolish conceit of the piece, which beneath its playfulness conceals a truth about the global maturity of jazz. The "poll" amounts to an interesting list of thoroughly accomplished musicians--and there's not an American on it. To read the whole thing, click here.Using words such as "unprecedented," "mind-boggling," "preposterous" and "what the s--t is going on here," the editors of BummedOut magazine, the country's leading Jazz periodical since the Original Dixieland Jass Band recorded "Livery Stable Blues," expressed their utter shock and disbelief this week when ballots submitted in the magazine's umpteenth Annual Critics' Poll listed not a single American-born musician among the winners or also-rans. What made the unparalleled result even more implausible is the fact that 98.6 percent of BummedOut's critics and reviewers live either in or around New York City and had never before voted for any musician west of the Ohio River.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary