main: December 2007 Archives

The French Jazz Academy has awarded pianist Roger Kellaway its Le Prix Du Jazz Classique for his 2007 CD Heroes. The album is by Kellaway's trio with guitarist Bruce Forman and bassist Dan Lutz. Nat Cole had such a drummerless trio and inspired Art Tatum to use the same instrumentation. Oscar Peterson, who adored Cole and Tatum, had a similar group from 1950 to 1958, with Ray Brown on bass, and guitarist Irving Ashby followed by Barney Kessel and then Herb Ellis. Although he is one of the great individualists among modern jazz pianists, Kellaway keeps the Cole-Tatum-Peterson tradition alive through the repertoire on Heroes. Peterson was one of Kellaway's major influences before Kellaway became a success on the New York scene at the age of twenty-two. They remained close musically and as friends. When I talked with Kellaway a couple of hours ago, he said, "Losing Oscar and getting this award in such close proximity makes me wonder if there's something going on--something mysterious."

The album is by Kellaway's trio with guitarist Bruce Forman and bassist Dan Lutz. Nat Cole had such a drummerless trio and inspired Art Tatum to use the same instrumentation. Oscar Peterson, who adored Cole and Tatum, had a similar group from 1950 to 1958, with Ray Brown on bass, and guitarist Irving Ashby followed by Barney Kessel and then Herb Ellis. Although he is one of the great individualists among modern jazz pianists, Kellaway keeps the Cole-Tatum-Peterson tradition alive through the repertoire on Heroes. Peterson was one of Kellaway's major influences before Kellaway became a success on the New York scene at the age of twenty-two. They remained close musically and as friends. When I talked with Kellaway a couple of hours ago, he said, "Losing Oscar and getting this award in such close proximity makes me wonder if there's something going on--something mysterious."

He said that he will go to Paris to receive the award January 7 in a ceremony at the Châtelet Theater. The French Jazz Academy Awards is the oldest and most serious music awards ceremony in France. Created in 1955, it is like the Grammy Awards with class. The voters are 60 independent journalists, photographers, writers and radio and TV producers. Kellaway was not nominated for a 2008 Grammy. Roger told me that while he's in Paris, he hopes to meet with Madame Eglal Farhi, the celebrated proprietor of the New Morning club in the Tenth Arrondissement. In France, New Morning is to modern mainstream jazz what the Blue Note was in the 1960s. It would seem a perfect fit for Kellaway.

The Canadian broadcaster Len Dobbin sent this Oscar Peterson anecdote to the Jazz West Coast listserve:

Oscar, after having visited friends outside of London, was waiting for a train back. The train station platform was on the foggy side when he spotted a man who looked familiar. He approached him and asked would he be Charles Laughton. Laughton replied he was and Oscar told him how much he enjoyed his work. Laughton then asked Oscar his name and what he did and when Oscar said he was a pianist, Laughton asked, "Jazz or classical?" When Oscar said jazz, Laughton asked him if he had any pot. Oscar's answer was negative. Laughton walked away.Pepper Adams told me that Laughton and Elsa Lanchester were known to serve pot as the post- dinner course at their home.

Len Dobbin

A new web site, The Sound, is devoted to Stan Getz and his music. The site is in its early stages but already has much of interest, including three pages of photos, ten videos and several full-length audio performances by Getz. The brief biography needs work. In the mold of the 21st Century show biz puffery that has crept into jazz PR, it has little biographical information and reads more like a tribute or a news release than a serious account of the artist's life. The real bio, a good one, is relegated to an easily overlooked link in small type that reads "detailed biography." The discography has no information beyond a chronological list of recording titles. The forum section operates under a set of admirable no-nonsense rules designed to keep discussions civil. The attractive site, which has great potential, is overseen by Getz's daughter Beverly. To visit the Stan Getz web site, click here.

I am adding to Other Places a link to Night Lights, a fine web log by David Brent Johnson of WFIU at Indiana University.

The current offering at JazzWax is a moving account of Jelly Roll Morton's last recording session and his shameful, racist, mistreatment by ASCAP. I don't know if film of Moton performing exists. But if you'd like an explanation and demonstration of Morton's piano style, you can't do better than this visit with Dick Hyman.

For those interested in knowing more about Oscar Peterson, the British journalist Steve Voce, in the British newspaper The Independent, provides a 2700 word obituary-as -essay. Among his anecdotes is one that illustrates the regard in which Peterson was held by other pianists. It also captures Duke Ellington's generosity and wryness. Peterson idolized Ellington, who was twenty-six years older.

Following Oscar Peterson on stage at a concert in 1967, Duke Ellington remarked: "When I was a small boy my music teacher was Mrs Clinkscales. The first thing she ever said to me was, 'Edward, always remember, whatever you do, don't sit down at the piano after Oscar Peterson'."

As for Peterson's effect on younger pianists, Voce tells this story:

Earlier, in 1945, a 16-year-old John Williams, later to be Stan Getz's pianist, was on tour in Canada with the Mal Hallett band and was playing in Montreal. "All the talk in the crowd was of a brilliant local pianist," said Williams, "and as we played, suddenly, between numbers, the packed audience in the dance hall parted like the Red Sea and this huge guy came up towards the bandstand. With some insight, I vacated that piano bench quick and he sat down. He played, and we were stunned. I had never heard anyone play like that."

Like all of Voce's posthumous portraits of musicians, his Peterson piece is thorough and illuminating. To read it, click here.

For a reminder that Peterson had modes other than flash and fire, watch this video clip of him teamed with another of his heroes, Count Basie. The bassist is Niels Henning Ørsted-Pedersen, the drummer Martin Drew. At the end, O.P. beams like a schoolboy who has just won a prize.

The sad news from Canada on this Christmas Eve is that Oscar Peterson died yesterday at home in Toronto. He was 82. One of the great piano figures of his time, Peterson was an inspiration to virtually every jazz pianist who followed him, his influence equaled only by his slightly younger contemporary Bill Evans.

Oscar Peterson

The Canadian national newspaper The Globe And Mail quotes Peterson's friend Tracy Biddle on his importance as a symbol to Canadians.

"He broke out of Canada. He's one of the first people. We talk of Celine Dion and Shania Twain and Alanis Morissette and Bryan Adams. Oscar Peterson did what they did years ago as a black person. So what he's done is incredible."The keyboard titan, who recorded almost 200 albums, played alongside the greats of the jazz world: Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Charlie Parker, Roy Eldridge, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie and Ella Fitzgerald.

"It makes you want to sing," the late Ella Fitzgerald once said of Peterson's piano work.

To read the entire Globe And Mail obituary, go here.

To remember Oscar at his happiest, watch this 1958 performance by his incomparable trio with bassist Ray Brown and guitarist Herb Ellis.

The New York Times today published a retrospective collection of articles about Peterson from the early 1990s to 2007. The definitive biography of Peterson is Gene Lees' The Will To Swing.

Kate McGarry, The Target (Palmetto). McGarry's singing evaded me. I don't mean that I didn't get it. I mean that I had never heard it. Then, during a recent engagement at Jazz Alley in Seattle, Luciana Souza mentioned that the guitarist appearing with her, Keith Ganz, was married to "the wonderful singer Kate McGarry." I took that as a recommendation. Back at Rifftides world headquarters, I listened to The Target. I'm glad I did. McGarry incorporates intriguing approaches to vocal color, timbre and phrasing that seem to come from folk and pop sources as much as from jazz . In the 1920s hit "Do Something," she swings as straight ahead as the young Anita O'Day. In Ganz's delightful "New Love Song," she evokes blithe sophistication worthy of Blossom Dearie. Steven Cardenas's "She Always Will," with McGarry's lyrics, might be the meditation of an Irish troubador. I much prefer her sinuous take on Sting's "Sister Moon" to the composer's.

Back at Rifftides world headquarters, I listened to The Target. I'm glad I did. McGarry incorporates intriguing approaches to vocal color, timbre and phrasing that seem to come from folk and pop sources as much as from jazz . In the 1920s hit "Do Something," she swings as straight ahead as the young Anita O'Day. In Ganz's delightful "New Love Song," she evokes blithe sophistication worthy of Blossom Dearie. Steven Cardenas's "She Always Will," with McGarry's lyrics, might be the meditation of an Irish troubador. I much prefer her sinuous take on Sting's "Sister Moon" to the composer's.

On several standards, McGarry maintains balance between respect for the song and a search for new possibilities. The resulting creative tension produces memorable versions of "The Lamp Is Low" and "The Heather On The Hill," in which she includes the seldom-heard verse of the Lerner and Loewe classic. In "It Might As Well Be Spring," she nudges and teases the time and succeeds in every harmonic chance she takes. Throughout, the intonation of her light voice is down the middle, even in the vocalese on a difficult unison passage with Ganz's guitar in Souza's demanding "No Wonder." McGarry's other accompanists are Gary Versace on piano, organ and accordian; bassist Reuben Rogers; drummer Greg Hutchison. On three pieces, there are solos by the daring tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin. Experts at illusive, suggestive improvising, Ganz and Verace solo on several tracks.

Don Redman was an important big band arranger and leader in the 1920s, '30s and '40s. He was not a bebop musician, but Redman may well have provided a catalyst for the creation of modern jazz in Eastern Europe following World War Two. With the help of pianist Emil Viklický and the venerable Czech jazz expert Dr. Lubomír Doruzka in Prague, I have been researching the emergence of bebop in Czechoslovakia. I have much to discover and verify, but it is clear that music pioneered by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie appeared in Prague after Redman's European tour in 1946, possibly because of it. The band included tenor saxophonist Don Byas, a key figure as the music evolved from swing to bop. Assuming that the band personnel was the same as that on this recording made in Switzerland during the 1946 European tour, Redman's group also contained the young pianist Billy Taylor, rapidly developing as a bop player. REDMAN

REDMAN BYAS

BYAS TAYLOR

TAYLOR

Jan Hammer, Sr., and other members of the Kamil Behounek big band from Prague heard the Redman band in Nürnberg, Germany, where they were also playing. Apparently, the American and Czech bands appeared opposite one another and the musicians interacted. One can imagine Byas, Taylor and others in Redman's outfit showing the young Czechs the harmonic and rhythmic mysteries of bebop. Soon, Hammer and others formed a bebop quintet that played regularly in Prague's Café Pygmalion until the Communist coup in 1948 resulted in a cultural freeze that sent jazz underground. Thanks to Dr. Doruzka, I have heard three pieces the group recorded in 1948. Their grasp of the idiom and level of achievement are impressive. Solos by Dunca Brož compare favorably with the playing of the best young American bop trumpeters of the period. The arranging in a piece by Brož called "Šero" ("Slight Darkness") is first-rate jazz impressionism. As I learn more about this intriguing period in European jazz, I will share it with you.

In the meantime, here's a reminder about Don Redman: He was an arranger for Fletcher Henderson in the 1920s and a had a fine big band of his own in the '30s. He was an accomplished alto saxophonist and clarinet player and always hired good musicians. He wrote two hits, "Cherry" and "Gee Baby, Ain't I Good To You." Redman was active through the 1950s and recorded with a big band as late as 1959. He died in 1964. I found one piece of video on YouTube. It is contrived nonsense in the usual style of Hollywood soundies of the period, but under the goofy duo singing "Nagasaki" you'll hear an example of Redman's scoring for saxophones. To view the clip, go here.

As the anonymous YouTube contributor suggests in his comment, the shorter of the two singers looks and sounds like Leo Watson. Can anyone among Rifftides Readers verifty his identity?

Go here for the 1929 McKinney's Cotton Pickers recording of Redman's "Gee Baby Ain't I Good To You" with his alto sax solo and sui generis talking/singing vocal. It's his arrangement, of course. In the photo that accompanies the recording, Redman is the short man in the middle.

Following a succession of deaths in the top ranks of jazz, it is a pleasure to tell you about an elderly musician who is getting attention because he is alive. The veteran rhythm guitarist and teacher Lawrence Lucie has passed the century mark. Here is an excerpt from today's New York Times story about Lucie.

The veteran rhythm guitarist and teacher Lawrence Lucie has passed the century mark. Here is an excerpt from today's New York Times story about Lucie.

On the eve of his 100th birthday on Monday night, Mr. Lucie, sitting in a wheelchair, could not go 20 seconds without receiving an embrace, a pat on the back or a handshake from one of the many jazz connoisseurs gathered at the offices of the musicians' union in Midtown Manhattan. The well-wishers were there to pay homage to his legacy.And it is quite impressive.

He is the last living person to have performed with Duke Ellington at New York's legendary Cotton Club. He played with Benny Carter at the Apollo Theater in 1934, the year it opened its doors to black customers. He played with Louis Armstrong for several years and was the best man at his wedding.

To read the whole thing, go here.

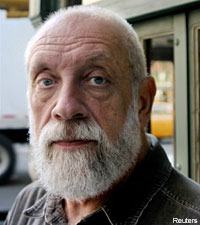

As nearly everyone in the jazz community knows by now, Joel Dorn died of a heart attack on Monday at the age of 65. Joel's work as a producer covered a broad swath of popular music, but many of us admired him for the integrity of his efforts with jazz artists when he was a key figure at Atlantic Records and in his ventures as an independent producer. Among the musicians who respected him for his knowledge, taste, guidance and quiet, wacky humor were Roland Kirk, Charles Mingus, Fathead Newman and Eddie Harris.

Joel Dorn

Later, with his own label, 32, and for Rhino Records, he set high standards for jazz reissues. Dorn provided CD booklet preambles that were slightly off the wall and always perceptive. Here's part of one for a Paul Desmond compilation:

To me, he's always been a painter with a palette full of pastels and a real soft brush.He seems to whisper into the horn, never saying a wrong word. In all the years I was in the studio or hanging out in joints, I never saw Desmond. Never even met him. But then I never ran into Monet in those places, either.

During the 1970s Dorn and I encountered one another now and then in New York. He was a stimulating companion with sharp perceptions and a dry wit. One evening following a record release party, we were walking east on 44th street with the trombonist Eddie Bert and the writer Burt Korall. We were discussing the quality of reviews in Down Beat. I forget who delivered the last installment of the rant before Joel capped it. Affecting a Groucho Marx delivery, he said, "You pay five dollars for a review, you get a five-dollar review."

Adjusted for inflation, the pay for reviews has gone up, but the Dorn principle still applies to an appalling percentage of them.

For a thorough and, as far as I can tell, accurate, report on his productive career, click here. For examples of his superb reissue work, try this Paul Desmond collection or these surveys of the Atlantic recordings of Rahssan Roland Kirk and Yusef Lateef.

Joel Dorn, 1942-2007.

Frank Morgan, an alto saxophonist who lost and then found himself, died yesterday in Minneapolis, his hometown. He was a few days short of his seventy-fourth birthday. In his last two decades he was productive and relatively contented, rid of his bedeviling habits and living with family members who cared about him.

Here is some of what I wrote about Morgan for one of his last CDs.

At eighteen, fully immersed in the L.A. jazz scene, he recorded with Wardell Gray and in his early twenties made his own album with Gray, Conte Candoli, Carl Perkins, Leroy Vinnegar, Howard Roberts and Larance Marable as his sidemen. His talent and hard work, his adoration and study of Charlie Parker, resulted in his sounding amazingly like his idol. Parker had burned himself out by then, dead of self-abuse in the spring of 1955 at the age of thirty-four. Morgan appeared to be headed for the same end. For the next thirty years, his addiction had him in prison much of the time. He did not entirely disappear from music, but to most listeners he was just a bright young alto player on a few old LPs and an entry in The Encyclopedia of Jazz. He became a featured soloist in bands at San Quentin and Chino and, later, with other recovering addicts at Synanon.By the mid-1980s, he had had enough. He told writer David Grogan, "I couldn't be Little Frankie, the child prodigy, forever, and I think I preferred facing defeat by heroin to facing whether I could really cut the mustard. Then I ended up falling in love with my drug habit." He shook off the habit and wrote finis to his prison career. In 1985, he found himself in a recording studio. It didn't take long for the first album of the new Morgan era to become a success. He's been going strong ever since.

Morgan recovered from a stroke in 1998 and continued his career. Late last month, his doctors discovered that he had colon cancer. It was inoperable. He moved out of a hospital and spent his last days at home. According to the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, he knew that he was dying and said to his manager, "Ain't it great to be alive?"

Tom Harrell, Dado Moroni, Humanity (Abeat). In six duets, the incomparable American trumpeter and the veteran Italian pianist achieve the most elusive of artistic goals, beauty through simplicity. Moroni's title tune is good company for five classic standards. I'm glad that this is a CD, not a vinyl record, or I would surely wear it out listening repeatedly to Harrell's solo on "Darn That Dream."

The Harry Allen-Joe Cohn Quartet, Music from Guys and Dolls (Arbors). Not that he's ever gone out of style, but musicians seem to be rediscovering Frank Loesser. Loesser's "Guys and Dolls" songs are among his best. Allen and Cohn do nothing innovative or revolutionary with the songs from Loesser's unforgettable Broadway musical. They simply improvise on them with affecting verve and imagination. Allen's tenor saxophone often evokes comparisons with Stan Getz, Zoot Sims and Ben Webster. In this collection I hear a substantial Al Cohn component in his playing. Maybe something has rubbed off in his recent intensive work alongside Cohn's guitarist son Joe. Rebecca Kilgore and Eddie Erickson are guests on several of the pieces, singly and together. Erickson is good. Kilgore is remarkable, one of the best interpreters of superior songs since Frank Sinatra.

Jennifer Higdon, City Scape, Concerto for Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Robert Spano (Telarc). My friend Jack Brownlow had a sixth sense for seeking out first-rate contemporary classical composers. Shortly before he died this fall, he sent me this CD containing two imposing works by Higdon, a protégé of Ned Rorem. He attached a post-it note reading, "24 Stars--a Masterpiece!" Bruno was not given to hyperbole. It's a masterpiece.

Steve Nelson, Sound-Effect (HighNote). The vibes player with the weightless touch and endless harmonic resourcefulness teams up with a dream rhythm section of pianist Mulgrew Miller, basist Peter Washington and drummer Lewis Nash. The program includes, on the one hand, a lightning "You and the Night and the Music," on the other Nelson's impressionist ballad "Sound Essence." Between those extremes of mood there are Freddie Hubbard's waltz "Up Jumped Spring," Ahmad Jamal's "Night Mist Blues" in an irresistible medium groove, "Desifinado" perking along on Nash's bossa nova beat, and the lovely, little-known James Williams waltz "Arioso." A satisfying album.

Marc Myers' current venture on his blog JazzWax is a conversation with the respected writer Dan Morgenstern, who says:

You have to be very careful not to let the bonds between you and musicians cloud what you're saying. If you're a writer, your responsibility always is to the reader or listener. If you shortchange your audience, you'll lose your credibility. I tried to avoid such conflicts by simply not writing about bad performances unless I had to. At that point, I'd always frame my remarks by saying that the artist didn't have a particularly good night rather than completely trashing him.

Dan Morgenstern

Morgenstern is director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University. This year, he won a Jazz Masters Award from the National Endowment for the Arts, only the second writer to be so honored; Nat Hentoff received the award in 2004. To read all of Dan's JazzWax interview, which includes news about a Louis Armstrong CD never before issued, go here.

Jazz historian Ted Gioia has launched an ambitious new web site. It is called Jazz.com. It encompasses a blog, a forum and an interview section. Its Encyclopedia of Jazz Musicians feature has enormous potential for listeners, musicians and researchers, indeed for the entire jazz community. In its initial appearance, the Encyclopedia is missing a number of notable musicians, but it solicits readers to suggest improvements. As it expands and undergoes refinements, it could become invaluable. Welcome to the web, jazz.com.

Truth is rarely pure, and never simple. -- Oscar Wilde

Simple isn't easy. -- Red Mitchell

Rifftides reader Duncan Reid responds to our recent suggestion that trumpeter Jack Sheldon gets less recognition than his talents warrant.

A thought on Jack Sheldon's lack of recognition. Like Cal Tjader, Vince Guaraldi, Shorty Rogers, Jim Hall, Conte Candoli, Paul Horn, Jimmy Giuffre and many others, he is white and based on the West Coast. Many critics, mostly on the East Coast and in Europe, have felt and still feel that white musicians do not play authentic jazz. The late French critic Hughes Panassie said just that. Moreover, I was told by the late Al Mckibbon that Leonard Feather's assessment of Cal was as follows, "Sunny and Californian with no weight at all."Ken Burns and Wynton Marsalis are among those with that attitude. You'll remember, as I assume you viewed the film Jazz, that aside from a brief segment on Brubeck and a few passing comments on Mulligan and a few others, Mr. Burns completely ignored West Coast jazz. In my opinion, much of what was said about white musicians was racist and derogatory. For instance, (historian) Gerald Early said that all the greatest jazz musicians are black because, "you got to have that feeling, you know, you got to have that feeling." (Critic) Nat Hentoff said, "West Coast jazz is white and bland." Of course, neither man was speaking the truth, just their perception. Wynton Marsalis just avoided talking about white musicians, save for Bix and a brief comment on Goodman. That is quite an accomplishment, considering the film lasted 18 1/2 hours. All of this lit a fire under me and is one reason I started writing a biography on Cal Tjader three years ago. Hopefully I can finish sometime next year.

Ramsey comments:

I agree that, despite the continued availability of most of his best work, Tjader's contributions are too little recognized. A thorough Tjader biography would be an important addition to the literature. Whatever animus toward Tjader Al McKibbon may have attributed to Leonard Feather, in the 1960 edition of The Encyclopedia of Jazz, Feather wrote,

Despite his increasing identification with Latin music, Tjader is still active in regular jazz and is a first-class performer with, as John S. Wilson has said, "a light touch and a propulsive approach."

Certainly, Ken Burns' Jazz series, for all of its virtures, had willful blind spots, too many to enumerate. To point out a few, Burns gave the slightest acknowledgement of the existence of Jack Teagarden and Bill Evans, white musicians of enormous importance. He was, however, an equal opportunity slighter; he also all but ignored Teddy Wilson and Benny Carter.

Jim Hall and Jimmy Giuffre have not been based on the West Coast in decades. They have both lived in the northeastern United States for more than thirty years. Paul Horn lives in Arizona and British Columbia. Shorty Rogers, Vince Guaraldi and Conte Candoli are no longer alive. But, as Robert Benchley said when he was informed of the death of George Gershwin, I don't have to believe it if I don't want to.

I don't mind being the butt of a joke, if it's a funny joke. --Kenny G

I hear that Kenny G is going make a jazz album. It will be called 'Round Noon. --Brad Terry

Marcus Printup, Emil Viklický Trio, Jazz na Hradĕ (Jazz at Prague Castle) (Multisonic). Trumpeter Printup spent a substantial part of the year touring Europe with pianist Viklický's impressive group. They reached a peak of intensity in this concert introduced by Czech President Vaclav Klaus. Printup, Viklický, the astonishing bassist František Uhlíř and drummer Laco Tropp shine in extended performances of four Viklický compositions plus "Dolphin Dance" and "Body and Soul."

Jon Hamar, Hereafter (Jon Hamar). Authority, power and lyricism from an impressive young bassist, with John Hansen and Dawn Clement sharing piano duties, Jon Wikan and Byron Vannoy alternating on drums. The CD includes John Lennon's "Julia," nicely arranged by Clement, and Astor Piazolla's "Todo Fue," but Hamar's compositions predominate. It requires clarity of conception and execution to successfully open an album with an unaccompanied bass solo. Hamar has both. He gets your attention and keeps it.

Alexander String Quartet, Fragments, vol. 2: Shostakovich Quartets 8-15 (Foghorn Classics). In these demanding, rewarding last quartets by the Russian genius, the Alexanders exercise their considerable virtuosity without wearing technique on their sleeves. The flow and passion of their interpretations put this collection on a level with the best performances of what may well prove to be Shostakovich's most enduring music.

Rifftides reader Ken Deifik writes:

Thanks for pointing out the Bill Evans Newsletter availability. It's not easy to download the entire set of 26 PDFs, so I've uploaded an archive of them to this web site.They will be available for only a few days. It's a large archive, over 300 Megs, so dialup users might want to consider just reading the PDFs online.

Thanks to Mr. Deifik for his helpfulness.

Glenn Mitchell's account of the 90th birthday party for Howard Rumsey a month or so ago at Catalina's in Los Angeles included this about Jack Sheldon's appearance with his sextet:

They played a favorite of Rumsey's, a tune that bassist Jimmy Blanton (his all-time favorite) was remembered in, "Do Nothing 'Til You Hear From Me." They continued with "Jumping At The Woodside" (same changes as "I've Got Rhythm") and "I Can't Get Started," which Sheldon sang very well. Sheldon is not only a great horn player and vocalist but a comedian as well. He roasted Rumsey for a number of minutes, telling stories from the past and kidding him with, "This is your party, Howard, wake up, " having fun with him about being 80 and surprised with 90 being actually realized. He acknowledged two great qualities of Rumsey -- his kindness and generosity.

That triggered a vision from the past. In 1954, I drove from Seattle to Southern California on spring break from college. On a Sunday afternoon in Hermosa Beach I visited the Lighthouse, where Rumsey headed the famous band of all-stars named after the club. Between sets, he and I struck up a conversation. Rumsey said, "Be sure to stick around. A kid from the neighborhood is going to sit in. I think you'll like him." The kid was Jack Sheldon. I liked him. Ever since, I have wondered that a trumpet player so accomplished, so admired and respected by other musicians, has never got his due from critics or the jazz audience at large. Maybe it's because of his comedy, which can be beyond raunchy. Maybe it's because he sings. Maybe it's because he has an acting career on the side. But make no mistake, for half a century Sheldon has been a formidable trumpet player.

Jack Sheldon

Here is a rare video example of his singing and playing. It was at a club in New Orleans. The rhythm section is Dave Frishberg, piano; Dave Stone, bass; Frankie Capp, drums; and John Pisano, guitar.

Googling, I found a promo for a documentary about Sheldon. I've turned up no information about when it will materialize.

Sheldon is the trumpeter who breaks your heart with the beauty of his playing in the main title and recurring "Shadow of Your Smile" theme of the motion picture The Sandpiper, a film whose only distinction is Johnny Mandel's music. To hear some of it, including Sheldon's solos, click here.

Jack Sheldon turned seventy-six a few days ago and seems to be flourishing. Hooray.

Rifftides reader and Bill Evans specialist Jan Stevens alerts us to a trove of Evans material that until now existed only in print archives. He reports that Win Hinkle, editor of Letter From Evans, has made all issues of his newsletter available free on the internet. Hinkle's subscription newsletter was published from 1989 to 1994. It included interviews with Evans, transcriptions of his solos, reviews, and contributions from or interviews with musicians close to Evans. Among those musicians were Chuck Israels, Kenny Werner, Hal Galper and Jack Reilly. For details, go to Mr. Stevens' website, The Bill Evans Webpages.

Well, it's about time.

Exigencies of the past few weeks have required putting off a number of duties, including the posting of a new batch of Doug's Picks. But there they are, in the right-hand column.

Here is a listening tip for Friday, December 7, gleaned from a Dave Brubeck Quartet listserve:

To celebrate pianist Dave Brubeck's 87th birthday, Alyn Shipton introduces part of a conversation with Brubeck recorded during his quartet's 40th anniversary tour of the UK, in which he selects some of his favourite recordings from a catalogue that includes over 100 albums.As well as such perennial favourites as "Take Five" by his historic quartet with Paul Desmond, Brubeck also looks at his collaborations with Gerry Mulligan, the London Symphony Orchestra and his present day band with saxophonist Bobby Militello.

That will be on BBC Radio 3 at 10:30 pm London time. In the US that's 5:30 pm EDT, 2:30 pm PDT. For internet listeners, BBC 3 has streaming audio.

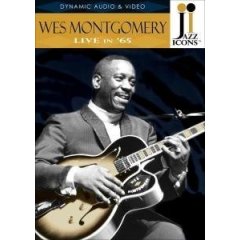

Wes Montgomery, Live in '65 (Jazz Icons). Anyone interested in guitar at the highest level will be fascinated by this DVD. If you are intrigued by the democratic, cooperative nature of jazz, you will relish the first segment. Sitting in a television studio in Holland with a rhythm section he is apparently meeting for the first time, Montgomery walks pianist Pim Jacobs through a tune whose name the guitarist doesn't know. The song turns out to be "The End of a Love Affair." Montgomery is relaxed and articulate. He is definite and specific about the altered harmonic progression he wants, spelling out the chords both instrumentally and verbally.

As Pat Metheny emphasizes in his erudite liner notes, this is not the instinctual primitive genius of the myth that has been built up around Montgomery's memory. Montgomery knows what he is doing and articulates it in specific musical terms. He and Jacobs negotiate the nature and placement of the chords, and the band comes to agreement about how to proceed. Montgomery is at ease with Jacobs, Pim's bassist brother Ruud and the energetic young drummer Han Bennink, who was becoming the ubiquitous and eclectic force in European music that he remains today. They clearly adore Montgomery and seem a bit stunned at finding themselves playing with him. But play they do, soaring on the energy and thrust that Montgomery inspires with his virtuosity. They nail not only "The End of a Love Affair," but also a fine version of "Nica's Dream" and a spontaneous blues. From his smiles, it is clear that Montgomery is pleased.

Two days later in a TV studio in Belgium, Montgomery is with a familiar rhythm section, pianist Harold Mabern, bassist Arthur Harper and drummer Jimmy Lovelace. If there were runthroughs, we don't see them. The quartet cooks through five pieces including Coltrane's "Impressions" and Montgomery's challenging "Jingles." As in Holland, excellent camera work and direction give the viewer vantage points from which to observe Montgomery's celebrated use of his thumb rather than a pick. His unorthodox technique, his octave lines, his polyphony, his harmonic and rhythmic daring have merged into standard jazz guitar language, but forty-two years ago they still seemed revolutionary. This is a rare opportunity to observe details of his approach. Guitarists will be studying the closeups of Montgomery's hands on the strings and fingerboard for a long time.

The final segment on the disc is from March, 1965, recorded in London under somewhat contrived conditions. Saxophonist and entrepeneur Ronnie Scott, with his back to Montgomery, explains the musician and his music as Montgomery sits like a studio prop. Scott does his part to perpetuate the legend of Montgomery as unable to read music. If that was technically correct on some level, Montgomery was fully schooled in detailed understanding of harmony, as he proved in Holland. A bit more subdued than in the earlier segments, Montgomery nonetheless plays beautifully with the rhythm section that was accompanying him at Scott's club; pianist Stan Tracey, bassist Rick Laird and drummer Jackie Dougan. There are versions of "Twisted Blues" and "Here's That Rainy Day" to compare with those a month earlier in Belgium. We also see and hear workouts on "Full House" and "Four on Six," Tracey's solo on the latter disclosing his appreciation of Thelonious Monk.

One of the most telling sequences showing Montgomery's thumb at work comes behind the DVD's closing credits as he plays "West Coast Blues." This disc is a highlight of the superb second batch of Jazz Icons DVDs.

Have you ever wondered what happened to Hal Gaylor?

Oh. You don't know about Hal Gaylor.

In the 1950s and '60s, Gaylor was one of the most respected bassists in jazz, working with a range of musicians. Here is what I mean by range; his colleagues included Chico Hamilton, Paul Bley, Stan Getz, Bill Evans, Clark Terry, Roger Kellaway, Lena Horne, Mel Torme, Anita O'Day, Jeremy Steig and Benny Goodman. There were many others of equal stature. Later, he was in the rhythm section that backed Tony Bennett. For a time, his trio with Walter Norris and Billy Bean collaborated with Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry. Here is what I wrote about The Trio when its only album was reissued on CD in 1999.

Of the many groups that have caused ripples on the surface of jazz and then sunk out of sight, none was more intriguing or seemed to have greater musical possibilities than The Trio. It was a cooperative group whose members poured all of their considerable abilities into creating a piano-guitar-bass group that was much more than just another wannabe Nat Cole Trio. Conceived by bassist Hal Gaylor, it was also an outlet for pianist Walter Norris and guitarist Billy Bean. The trio's intricacies were reminiscent of Cole at times but also of the Red Norvo Trio and of adventurous groups like those of Lennie Tristano. Not long after this recording, Bean disappeared into his native Philadelphia. Gaylor left jazz to become a certified drug counselor. Only Norris remains active in music. The Trio is a valuable reminder of a splendid group.

As Robert Gados reported over the weekend in the Middletown (New York) Times Herald-Record, Gaylor did not leave jazz on a whim.

THE MUSIC STOPPED FOR GAYLOR, who lives in Scotchtown, in 1973, when a virus left him deaf in the right ear. He was 44 years old. He went to a doctor in San Francisco because his ear was clogged. The doctor told him, "The cochlea is dead." Tough news to hear for anyone; for a top jazz musician, a professional death sentence.

To read all of Gados's story, go here.

Then go to Gaylor's own web site to read more details of his life as musician, architect and artist, and to see his portraits of musicians.

Hal Gaylor wearing

his portrait of

Ornette Coleman

I asked the writer Gene Lees and the pianist Roger Kellaway for a few words about Gaylor.

Lees: I first knew him in Montreal when we were kids, twenty-three or twenty-four years old. He was already established. I was working as a reporter and hanging out in the jazz joints. He was a great man and a great musician. We have been extremely close friends from that time 'til this. An amazingly multi-talented guy. He's like a brother to me. I haven't seen him in years, but we talk on the phone all the time.

Kellaway: Hal was in my first recorded trio, when he was with Tony Bennett. I just loved his playing. He was a fabulous bassist, very musical, and swung his ass off. We've made the masters of those recordings into a CD. We haven't released it.

That's something to look forward to.

This is short notice, but here's a message from pianist-composer Joan Stiles:

Tonight, Sunday, Dec. 2nd, 11pm-midnight EST: "Jazz from the Archives" show on WBGO (88.3 FM). I'll be interviewed by Annie Kuebler, archivist and curator of the Mary Lou Williams collection at the Institute of Jazz Studies. We'll be playing selections from Hurly-Burly. You can listen online by going here.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary