main: October 2005 Archives

The posting about Willis Conover brought the following message from one of his Voice of America colleagues, John Birchard.

I came to VOA in 1993, hired as a news broadcaster on the late night shift. Because of my hours, I almost never saw Willis, except for once in a while when he would be out on the steps of the building chatting with the smokers. I never felt right about horning into his conversations, just to say I admired his work... but I did note his shrunken figure and face and the big horn rims.

Early on, I got the impression that quite a few people—in middle management and above—looked upon him as the tail that wagged the dog, that he was entirely too big, but there was nothing they could do about it. When he died, other than a fairly perfunctory obit, there was little to indicate that anything important had happened. VOA continued to run his tapes week after week, month after month. I don't know the story of the efforts to get him the Presidential Medal of Freedom—or the manner in which he was treated in connection with the White House Jazz Festival, but I can imagine the kinds of small minds at work to bring him down to their level.

One personal anecdote: During the decade of the 70s, Quinnipiac College (now University) in Hamden, Connecticut, played host to an annual intercollegiate jazz festival, featuring college bands from all over the east and midwest. The performances were judged by a panel of professional musicians and others which, at various times, included Clark Terry, Jimmy Heath, Ernie Wilkins, Chico O'Farrill, Father Norman O'Connor and Jimmy Lyons. During those years, I was a talk show host in New Haven and the festival producers saw fit to have me emcee the programs each Spring. The festivals ran from Friday through Sunday nites. But I had to do my talk show on Fridays 'til 9pm, so each year the producers would have someone fill in for me for the first hour of the evening. One Friday evening, I walked into the back of the hall and heard a familiar voice from up on stage.

Of course, it was Willis. Not many in the audience really knew who he was, but I did. I was convinced I had just lost my gig. I trotted backstage and one of the producers gave Willis the high sign and he introduced me, gracious and appropriate as always. As he walked offstage and I walked on, we shook hands and I thanked him. Then, to the audience, I said, "I'm not sure you know just how intimidating it is to have the most famous jazz disc jockey in the world substituting for me. I'm proud to share the same stage with Mr. Conover and it's an honor to have him here."

Mr. Birchard still broadcasts the news for the Voice of America.

For an obituary of Willis Conover, go here.

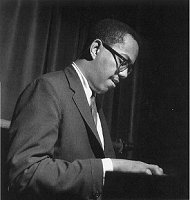

The White House did once treat Conover with respect. In 1969 it chose him to organize the musical portion of the 70th birthday party that President Nixon gave for Duke Ellington. Willis recruited the all-star band and produced and narrated the concert. I took a picture of him that afternoon at the rehearsal in the East Room as he listened to Hank Jones, Gerry Mulligan, Paul Desmond, Clark Terry, Bill Berry, J.J. Johnson, Urbie Green, Jim Hall, Louis Bellson, Milt Hinton, Joe Williams and Mary Mayo. The concert was finally released on a Blue Note CD in 2002. I was honored to write the liner essay. Here's a bit of it.

Hank Jones, Billy Taylor, and Dave Brubeck played beautifully, but the hands-down winner in the piano category was the 65-year-old Earl Hines, who in two daring minutes of “Perdido” tapped the essence of jazz. Ellington stood up and blew him kisses. Later, Billy Eckstine, who sang with Hines’ band before he had his own, walked up to his old boss and gave him an accolade: “You dirty old man.” The concert lasted an hour and a half, and the room was swinging. I looked around at heads bobbing and shoulders swaying and found Otto Preminger beaming and snapping his fingers Teutonically, one snap at the bottom of each downward stroke of his forearm.

Urged onto the platform, Ellington improvised an instant composition inspired, he said, by “a name, something very gentle and graceful—something like ‘Pat.’” The piece was full of serenity and the wizardry of Ellington’s harmonies. Mrs. Nixon, who looked distracted through much of the evening, paid close attention.

The evening was Ellington's, gloriously so, but it was Willis's connections, coordination, organizational skill and stewardship that put the icing on the birthday cake. It was one reason among many larger ones that he deserved, and still deserves, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Thanks so much for your piece about Willis Conover, and for all your other writing. I read your site regularly and am enlightened and informed every time.

My one experience with Willis Conover is worth sharing if only to mirror your sentiments. Years ago, probably 30 or so, a old family friend who lived in WC's apartment building and was a good friend of his, asked me if I would like to visit WC and have a chat. I have always been a musician and for my entire life have done both music and my "day gig" as a school person. But in the history of western music I have no place and for anyone other than WC, I was simply another speck. He treated me as royalty, as a musical person in my own right and gave me so much counsel, encouragement, wit, humor, imagination, kindness and respect. What an amazing couple of hours I had with him. I have never forgotten WC and his extraordinary interest and kindness. They don't make them like Willis Conover anymore.

With thanks,

peter kountz

Dr. Kountz's achievements in education make him much more than a "school person." To see them, go here.

Bill Kirchner, a musician who is also an educator, writer, editor and producer, knew Willis Conover. Like at least ninety-nine percent of jazz musicians, he is a fan of Johnny Mandel, one of whose arrangements recorded by Conover’s big band more than fifty years ago is responsible for setting off this chain of reminiscences about Willis. Bill writes:

Nice memories of Willis. I had fun hanging out with him in DC years ago.

There is a stunning, groundbreaking chart by Johnny (at age 21!) on that album of "The Song Is You" in ballad tempo, originally written in 1947 for, of all people, Buddy Rich. It is one of the first instances I know of in jazz scoring of genuine counterpoint. I tried to include it in the Smithsonian Big Band Renaissance box, but couldn't get the rights from Universal.

Big Band Renaissance, produced by Bill Kirchner in the nineites, and its predecessor boxed set, Big Band Jazz produced by Gunther Schuller and the late Martin Williams in the eighties, are invaluable historical collections. They were released by The Smithsonian Collection of Recordings but were allowed to go out of print long ago. The copies still available are precious items.

To the complaint, "There are no people in these photographs," I respond, "There are always two people: the photographer and the viewer." —Ansel Adams

Don’t play what’s there, play what’s not there —Miles Davis

Rifftides Reader John Thomas noticed the recent postings about Johnny Mandel and kindly loaned me a CDR copy of a rare vinyl album containing Mandel’s arrangement of “The Song Is You.” The 1953 Brunswick LP has been out of print for at least forty years and reissued on CD only in a limited Japanese edition. It is called Willis Conover’s House of Sounds: Willis Conover presents THE Orchestra. THE Orchestra was a first-rate Washington, DC, band led by Joe Timer. It included wonderful players like Earl Swope, Jack Nimitz and Marky Markowitz. Conover was a local broadcaster whose accomplishments included helping to desegregate Washington by requiring that blacks be admitted to clubs in which he organized concerts.

Through most of the cold war, Conover was the host of Music USA on the Voice of America. He was never a government employee, always working under a free lance contract to maintain his indepence. While our leaders and those of the Soviet bloc stared one another down across the nuclear abyss, in his stately bass-baritone voice Willis introduced listeners around the world to jazz and American popular music. With knowledge, taste, dignity and no trace of politics, he played for nations of captive peoples the music of freedom. He interviewed virtually every prominent jazz figure of the second half of the twentieth century. Countless Eastern European musicians give him credit for bringing them into jazz. Because the Voice is not allowed to broadcast to the United States, Conover was unknown to the citizens of his own country. For millions behind the iron curtain he was an emblem of America, democracy and liberty. Gene Lees makes the case, to which I subscribe wholeheartedly, that,

…Willis Conover did more to crumble the Berlin wall and bring about collapse of the Soviet Empire than all the Cold War presidents put together.

In the January 2002 issue of his invaluable JazzLetter, Lees told Conover’s story, including an account of the attempts to have him presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The effort began when George H.W. Bush was president and continued into the current administration. Among those pushing for the honor when Willis was alive and after he died in 1996 were Lees, several other prominent writers and Leonard Garment, who was a White House counsel in the Nixon administration and had been a professional musician. The first President Bush, President Clinton and the second President Bush ignored all letters and presentations about Willis. Conover remains unrecognized by the nation for which he did so much. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the award recently presented to Paul Wolfowitz and other administration figures for their parts in the iraq war.

The JazzLetter costs $70 a year. Sometimes it arrives considerably after the monthly dateline of the latest issue. It is worth the money and worth the wait. Gene writes about music and other matters with skill, erudition and passion. Much of his JazzLetter work eventually makes its way into his books, of which there is now quite a number. Lees and the JazzLetter do not have a website. They do have an e-mail address and a mailing address.

genelees@sbcglobal.net

Gene Lees JazzLetter

P.O. Box 240

Ojai, California 93024-0240

It may be that if you subscribe you can talk Gene into giving you a bonus copy of the issue about Conover. After I read it, I wrote the following letter, which ran in the February, 2002 issue

Dear Gene,

I want to tell you about my last lunch with Willis Conover, but the story needs background. In 1968, Willis was the MC for JazzFest, the New Orleans jazz festival. He did a splendid job. As board members of the festival, Danny Barker, Al Belletto and I fought hard to persuade the board to accept Willis’s proposal that he produce the 1969 festival. The other board members knew as little as most Americans knew about Willis. We educated them. Over a number of contentious meetings and the strong reservations of the chairman, Willis was hired. The ’69 festival turned out to be one of the great events in the history of the music. It reflected Willis’s knowledge, taste, judgment, and the enormous regard the best jazz musicians in the world had for him.

I won’t give you the complete list of talent. Suffice it to report that the house band for the week was Zoot Sims, Clark Terry, Jaki Byard, Milt Hinton and Alan Dawson, and that some of the hundred or so musicians who performed were Sarah Vaughan, the Count Basie band, Gerry Mulligan, Paul Desmond, Albert Mangelsdorff, Roland Kirk, Jimmy Giuffre, the Onward Brass Band, Rita Reyes, Al Belletto, Eddie Miller, Graham Collier, Earle Warren, Buddy Tate, Dickie Wells, Pete Fountain, Freddie Hubbard and Dizzy Gillespie. The festival had style, dignity and panache. It was a festival of music, not a carnival. An enormous amount of the credit for that goes to Willis. His achievement came only after months of infighting with the chairman and other retrograde members of the jazz establishment who did not understand or accept mainstream, much less modern, jazz and who wanted the festival to be the mini-Mardi Gras that it became the next year and has been ever since. They tried at every turn to subvert the conditions of Willis’s contract, which gave him extensive, but not complete, artistic control. Because Willis was tied to his demanding Voice of America schedule in Washington, DC, much of the wrangling was by telephone and letter. He flew down to New Orleans frequently for meetings, which he despised as much as I did. He did not need all of that grief. He pursued his stewardship of the festival because he had a vision of how the music he loved should be presented.

The nastiness took its toll. When it was over, Willis was depleted, demoralized, bitter and barely consoled that he had produced a milestone festival. In the course of the battle, he and I became allies and close friends. As a purgative, he was going to write a book about his New Orleans experience, but I’m glad he didn’t; the issue is dead and so are many of the dramatis personae. Charlie Suhor covers much of the 1969 story in his book Jazz In New Orleans (Scarecrow Press). One night Willis and I were alternately commiserating and acting silly at the bar of the Napolean House over a couple of bottles of Labatt, his favorite Canadian ale. After a moment of silence, he turned to me and said in that deep rumble, “I love you, man.” The moment is one of my most precious memories. We were friends and confidants after my family and I moved to New York, where he had an apartment, and remained so after I left for other cities and we didn’t see each other for years at a time.

In 1996, not long after the scandalous treatment you described Willis receiving at the White House jazz festival, I was in Washington for a meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. It was about a month before he died. Willis invited me to lunch at the Cosmos Club, where he maintained a membership. I doubt if, at the end, he could afford it, but it was important to him to be there, to feel a part of the old Washington he loved. He was at the door of the club when my cab pulled up. In the year since I had last seen him, he had shrunk into an Oliphant caricature, his horn-rimmed glasses outsized on his face, his shoulders and chest pinched, sunken.Even his leonine head seemed smaller. His hair and his face were mostly gray. He led me to the elegant dining room, on the way introducing me to a couple of men. He had momentary difficulty remembering one of their names. At the table, Willis launched into a diatribe against his old New Orleans enemy, but gave it up and started reciting some of his limericks. He wrote devastatingly funny and wicked topical limericks. But this day it was all by rote. He was strangely absent, and his speech was irregular, partly because of the ravages of the oral cancer he survived and partly, I thought, because he must have had a stroke. I could not lead him into any topic long enough for a conversation to develop, so I sat back and tried to enjoy the limericks. He seemed to want to entertain me, and I imagine he was deflecting any possible attempt on my part to be sympathetic or maudlin.

I was due at a meeting and, after coffee, Willis asked the waiter to call a taxi for me. He walked me to the door and we stood silently in the entry of that magnificent old building. When the cab arrived, I had to say something. I didn’t want it to be “goodbye,” so I said, “I love you, man.” Willis swallowed and blinked. I gave him a hug and climbed into the cab. As it made a left turn out of the drive, I looked over at the entrance. Willis had disappeared into the Cosmos.

Doug

I intended to mention in the Rifftides ad hoc survey of recent trio CDs some by the Italian pianist Enrico Pieranunzi. Pieranunzi is another pianist who has retained the Bill Evans ethos and used it as the foundation for a style of his own. As if to remind me, today the mailbox disgorged the reissue of a selection of film music by Ennio Morricone, used for improvisation by Pieranunzi, bassist Marc Johnson and drummer Joey Baron. The album has U.S. distribution from Sunnyside Records and is available here.

Much of Pieranunzi’s work, including the first Morricone CD and Play Morricone 2, is on CamJazz, a classy Italian label. He, Baron and Johnson, Evans’ last bass player, work together with unity of purpose. They give the music, by turns, intensity and ease that perfectly suit the Morricone pieces. It may surprise listeners who associate Morricone’s music only with the mournful soundtracks of spaghetti westerns that some of his themes are as hip as bebop originals. The CamJazz catalogue is worth exploring for other Pieranunzi CDs, among them his recent duets with Jim Hall, the restlessly exploratory dean of modern jazz guitar. There is also a Pieranunzi collaboration with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian. Enrico Brava, John Taylor, Kenny Wheeler, Lee Konitz and the intriguing pianist Salvatore Bonafede are other CamJazz artists.

A Rifftides reader writes:

Keep up the great work on your site. It's a beacon of taste and erudition in the sometimes dispiriting world of jazz criticism.

All right. Another day or so.

Jaki Byard, Sunshine of My Soul (Prestige Original Jazz Classics). Byard, piano; David Izenson, bass; Elvin Jones, drums.

I wrote in a blurb for the 2001 reissue of this album, “Byard was one of the most disciplined and one of the least inhibited of all jazz improvisers.” With Ornette Coleman’s bassist and John Coltrane’s drummer, he spreads sunshine even as they hurtle headlong through space without guideposts in “Trendsition Zildjian,” eleven minutes of total improvisation. The track is amazing even in the context of this amazing recording. Made in 1967, its music will always be new. No one has solved the mystery of Byard’s murder in 1998 and no one has explained the mystery of his genius. Genuis is like that.

Mike Wofford, Live at Athenaeum Jazz (Capri). Wofford, piano; Peter Washington, bass; Victor Lewis, drums.

Reviewing Wofford’s first album, Strawberry Wine, in 1967, I described him as “an excellent piano player who is much under the spell of Bill Evans.There are some tracks on which Wofford's individuality shows. His approach includes humor, a quality many musicians his age have avoided like the plague." Thirty-eight years later, Wofford is still in the Evans tradition in terms of his touch, chord voicings, implied rhythms, and ability to generate a floating quality. But his individuality shows here on every track, as it has for decades. His mastery and, yes, humor, are priceless on Ellington’s “Take the Coltrane.” Wofford is based in San Diego. This was recorded just up the road in La Jolla. His sidemen are two of New York’s finest. They deserve to be in his company.

Dave Peck, Good Road (Let’s Play Stella). Peck, piano; Jeff Johnson, bass; Joe LaBarbera, drums.

Hiring Bill Evans’ last drummer and one of the leading exponents of the Scott LaFaro school of bass playing for this date, Peck clearly had no intention of disguising Evans’s influence. From the pianist’s ethereal introduction of “Yesterdays” through his composition “The First Sign of Spring,” which hints at Evans tunes, to the slowly decaying final chord of “She Was Too Good to Me,” Evans hovers benevolently over Peck’s stimulating session. The trio is beautifully integrated, sounding as if they had been working together night after night. “Just in Time,” “What is This Thing Called Love” and “On Green Dolphin Street” are swingers. Peck is reflective in two of Ellington’s loveliest ballads, “Low Key Lightly” and “The Star Crossed Lovers.” Good Road seems to me his best work on records.

Bobo Stenson, Goodbye (ECM). Stenson, piano; Anders Jormin, bass; Paul Motian, drums.

Tord Gustavsen, The Ground (ECM). Gustavsen, piano; Harald Johnsen, bass; Jarle Vespestad, drums.

In the lavish clarity of ECM’s sound, these CDs present impressive Scandinavian pianists. With Paul Motian as his drummer, Stenson, a Swede, would seem to be courting an Evans sensibility. Motian is too perpetually hip to encourage a return to those glorious days of yesteryear, although the trio comes closest to Evans in “Yesterdays.” Stenson has certain similarities to Evans in touch and harmonic voicings, but generally his work is more informed by Scriabin-like gravity—until the last piece. In Ornette Coleman’s “Race Face,” everyone scurries amiably and the pianist treats us to outré intervals. Great fun.

Fun does not come to mind in describing the work of Gustavsen. Beauty does. In the words of Guardian reviewer John Fordahm, the Norwegian “likes space, silence and ambiguity.” His music’s dreamy qualities have crossed him over into the feel-good, soft-jazz market, but his trio’s playing has enough harmonic density, backbone and guts that he’s never going to be mistaken for George Winston.

Quickly, then (I can’t stay up all night again), here are other piano trio CDs that I’ve allowed to move to the top of the stack:

Peter Beets, New York Trio, Page 3 (Criss Cross). Beets, piano; Reginald Veal, bass; Herlin Riley, drums.

Fine young mainstream Dutch pianist. Third CD on Criss Cross. Getting better all the time.

Jo Ann Daugherty, Range of Motion (BluJazz). Daughterty, piano; Lorin Cohen or Larry Kohut, bass; guitar, saxophones, trumpet, trombone.

Ms. Daugherty is from Missouri and lives in Chicago. There is only one trio track on her CD. The horns and guitar are all good, and so are her tunes, but that trio track, “Harold’s Tune,” is a gem. I had never heard of her when I put the disc on. I love surprises like this. Jo Ann Daugherty deserves—no, we deserve—a trio album, pronto.

Alexander Schimmeroth, Arrival (Fresh Sound). Schimmeroth, piano; Matt Penman, bass; Jeff Ballard, drums.

Schimmeroth is a young German living in New York. His sound is full-bodied, his timing and note placement exquisite. This is an impressive debut.

David Hazeltine, Modern Standards (Sharp Nine). Hazeltine, piano; David Williams, bass, Joe Farnsworth, drums.

One of the great pros among jazz pianists under fifty, always swinging, always satisfying.

Hod O’Brien, Live at Blues Alley, First Set, Second Set (Reservoir). O’Brien, piano; Ray Drummond, bass; Kenny Washington, drums.

O’Brien was active in New York in the fifties and remains an inspired exponent of the bebop style founded by Bud Powell. Drummond and Washington inspire him to some of his best playing.

Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them, well, I have others—Groucho Marx

As usual, there are piles of incoming compact discs in my office and the music room. Among those that I will want to hear more than once are several by the piano-bass-drums combination that for at least sixty-five years has been at the core of jazz. The piano trio, of course, functions as the rhythm section for big bands and combos. On its own, depending on the players and how they relate to one another, it is capable of nearly limitless flexibility, breadth, depth and variety. In this posting last month, I reflected on the importance of a piano trio that changed the state of the art. Here’s a short list of recommended trio CDs from among the stacks of fairly recent arrivals.

Kenny Barron Trio, The Perfect Set, Live At Bradley’s II (Sunnyside). Barron, piano; Ray Drummond, bass; Ben Riley, drums.

Three years ago in my Jazz Times review of this album’s predecessor, I wrote,

Barron takes "Solar" at a fast clip that does nothing to suppress his development of original melodic ideas or inventiveness in voicings. There's not a cliché to be heard.

Nor is there in volume two, unless sprinkles of Thelonious Monk seconds and whole-tone runs are to be considered clichés. Barron’s one solo track is a joyous ride on Monk’s “Shuffle Boil.” For the rest of the hour, the trio shines. Barron’s ballad tribute to Monk, “The Only One,” is a highlight, but not the highlight. The entire CD is a highlight by one of the best trios of this or any other period of jazz.

Don Friedman VIP Trio, Timeless (441). Friedman, piano; John Patitucci, bass; Omar Hakim, drums.

Since the very early 1960s, Friedman has been demonstrating that his thorough understanding of Bill Evans liberates him to be himself within the song form. For a pianist to be himself playing so indelibly personal an Evans piece as "Turn Out the Stars" is a monumental expression of individuality. At seventy,Friedman continues his growth, sounding more youthful and inventive than ever. Patitucci may be Friedman’s ideal bassist.

Jason Moran, Same Mother (Blue Note). Moran, piano; Tarus Mateen, bass; Nasheet Waits, drums; Marvin Sewell, guitar.

Okay, so it’s a quartet. But it’s a trio with a guitar grafted on, except for the integrated, and quite lovely, “Aubade.” After being puzzled by all the hype when Moran emerged a few years ago, I am beginning to fathom his iconoclastic approach, although I find it less profound and revolutionary than some do. He may have studied with Jaki Byard, a genius, but the publicity suggesting that he is Byard’s successor or reincarnation is massively unfair to Moran. Let’s wait a minute and see what he becomes. His trio treatment of Mal Waldron’s “Fire Waltz,” sans guitar, may hold a hopeful hint.

Mary Lou Williams 1944-1945 (Classics). Williams, piano; Al Lucas, bass; Jack Parker, drums.

This survey of a couple of important years in Williams’s career includes her suite “Signs of the Zodiac,” seven of whose twelve segments are with the trio. If you want to hear, in her prime, an influence on Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, this is a good place to start.

Bill Mays, Neil Swainson, Terry Clarke, Bick’s Bag (Triplet). Mays, piano; Swainson, bass; Clarke, drums.

Mays has two trios, the one with Martin Wind and Matt Wilson and this one, with two of Canada’s finest sidemen. Recorded at The Montreal Bistro and Jazz Club, having a fine night, they close with Bud Powell’s “Hallucinations," a good idea because the performance would have been hard to top.

Jon Mayer Trio, Strictly Confidential (Fresh Sound). Mayer, piano; Chuck Israels, bass; Arnie Wise, drums.

Without Mays’ sprung energy, Mayer is a relaxed and relaxing player with origins in the Bud Powell school. Here, he reunites with Israels and Wise. He played with them in Europe more than four decades ago. Their take on Powell's and Kenny Dorham's title tune is saturated with Bud's spirit, and Israels is in his most compelling walking mode.

The Christian Jacob Trio, Styne & Mine (WilderJazz). Jacob, piano; Trey Henry, bass; Ray Brinker, drums.

The brilliant pianist in a program of songs by Jule Styne (“It’s You or No One,” I Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry, and others) and originals by Jacob. The trio’s sometime boss, Tierney Sutton, sings a couple of tunes with the band. In the notes, Jacob's other sometime boss, Bill Holman, says, "Christian, Trey and Ray are masters; chops are in abundance, but only in the service of the music." Yup.

Steve Kuhn Trio, Quiéreme Mucho (Sunnyside). Kuhn, piano; David Finck, bass; Al Foster, drums.

Like the slightly older Friedman and the slightly younger Mays, Kuhn is a yeoman of modern jazz who earns more recognition than he gets. In this program of classic Latin American songs (“Bésame Mucho,” “Tres Palabras” and “Andalucía” among them), he is full of swing, refractive ideas and, at times, almost giddy good humor. Finck and Foster are superb behind, around, and weaving in and out of Kuhn’s inventions. A splendid album.

Hey, this is fun. Let’s do more tomorrow.

(To be continued)

Seek ye first the good things of the mind, and the rest will either be supplied or its loss will not be felt. —Sir Francis Bacon

In the right-hand column, you will find a new batch of Doug's Picks. Yes, I know; it's high time.

The whole problem can be stated quite simply by asking, 'Is there a meaning to music?' My answer would be, 'Yes.' And 'Can you state in so many words what the meaning is?' My answer to that would be, 'No.' —Aaron Copland

Acquaintance: Where are you living these days?Al Cohn: Oh, I’m living in the past.

I tend to live in the past because most of my life is there. —Herb Caen

The sad news from Devra Hall and John Levy is that Shirley Horn died last night. She had been unwell for several years. As DevraDoWrite, Devra just posted an excerpt about Shirley from her and John's Men, Women and Girl Singers. To read it, go here.

For the excellent NPR Jazz Profiles on this remarkable musician and enchanting singer, go here.

Yakima, Washington, where I live most of the time, has more attractions than trolleys and the legacy of William O. Douglas. Among them is a new place in which to hear music. Well, it's not a new place. It was built in 1917 and until recently was the Church of Christ, Scientist. Over the past few decades, the congregation, like many of its counterparts across the country, shrank. The church is moving to smaller quarters. After the possibility that the building might become an athletic facility or, worse, be torn down to make way for a parking lot, a family successful in the building trade and devoted to music, acquired it and determined to make it a concert hall.

As the Strosahl brothers, Pat and Steve, were reaching their final decision, they invited a few people to sit and listen to music in the main hall of this gorgeous building,  which might have been beamed over to Eastern Washington from the Italian Renaissance.

which might have been beamed over to Eastern Washington from the Italian Renaissance.

The test performances included a piano trio playing Beethoven, a group of singers from the Seattle Opera, a brass quintet and a jazz ensemble. The listeners included Brooke Cresswell, the conductor of the Yakima Symphony Orchestra; Jay Thomas, the eminent Seattle trumpeter; Thomas's wife, the singer Becca Duran; several other professional musicians; and me. After the second sound check, we arose from the pews and gathered under the magnificent dome to evaluate the sound. Our consensus and advice: don't change a thing. The room has the best natural acoustics I have heard since I listened to a string quartet from the back of St. Nicholas Church in Prague and the music was so clear that I might have been sitting in the midst of the group.

After negotiating an obstacle course of applications, permits, approvals and, in general, dancing a bureacratic

tango daunting even to seasoned builders, the Strosahls emerged with approval in the nick of time for their first concert. That was good, because they had hired the Bill Mays Trio to be the premier performers in what was now called The Seasons Performance Hall. Their plan is to concentrate on jazz and classical chamber music, incorporate tastings of the Yakima Valley's celebrated wines and make The Seasons an attraction not only for residents but also for visitors who flood into the valley to tour the vineyards and wineries.

The launch was a success. An audience of 350 heard Mays, bassist Martin Wind and drummer Matt Wilson—fresh from an engagement at Jazz Alley in Seattle—in an inspired two-hour concert. In the spirit of the name of the hall, Mays created a program of pieces that alluded to all of the seasons. They included an adaptation of a movement of Vivaldi's "Four Seasons," "Autumn Leaves," "Spring is Here" and "Snow Job," Mays' transformation of "Winter Wonderland." True to the sound check, the hall was a listener's dream. Amplification of the nine-foot Steinway was not only unnecessary but would have been a prosecutable crime. The dynamics of Wilson's drumming were crystalline, down to the tiniest whispers of his brushes and the subtlest pings and dopler effects of the little bell he sometimes flourishes. Wind cracked his bass amplifier almost impercebtibly, only enough to enhance the balance. It was a rarity in jazz today, an acoustic performance, warm and intimate, without electronic shaping or manipulation.

When the big department stores abandoned downtown Yakima, either to disappear entirely or move to an asphalt wasteland on the edge of town, it wasn't long before most of the small stores, without retail anchors to bring shoppers, drifted away. It is a problem common to many medium-sized American cities that have been, to use a generic term, Walmartized. There are dozens of plans and suggestions, many of them harebrained, to breathe life back into downtown. The Strosahls, bypassing commissions, committees and councils, have taken initiative with a cultural approach. With luck, community support, the right kind of publicity and advertising campaign, and bookings that maintain the quality of the opening event, The Seasons could be a catalyst for a downtown Yakima revival.

Jazz musicians have lots of stories from their gigs. Not to impinge on Bill Crow's territory, but here are three that the peripatetic Bill Mays sent me from the road following his Yakima gig.

I was playing the Knickerbocker in New York City several years ago. A man came up after the set and said "I loved every minute of it. I have all your records, and I love your work." Always a little suspicious of people who say they have "ALL my records."I innocently inquired "Really?—I'm curious—which one is your favorite?" He replied with a title that I didn't recognize. I said "I'm a bit confused—I never made a record by that name." He said, "But aren't you Cedar Walton?" I guess he'd never LOOKED at the backs (or fronts) of his LP collection and thought that as he was enjoying his cavier pie and braised liver, he was also enjoying the music of Cedar Walton.

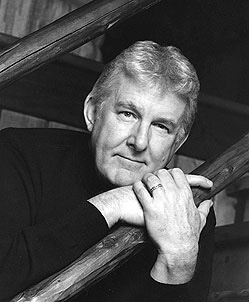

Mr. Mays (photo by Judy Kirtley) is on the left, Mr. Walton on the right.

Same club, the Knickerbocker; a man and his wife at a nearby table. It's a talky club and I never, of course, expect a rapt, silent audience. Anyway, this guy requested some tune. I played it, during which he talked continuously to his wife. Near the end of the set he got up, walked past the piano and indignantly said "I never heard my tune". I replied "That's because you talked through it the entire time." He did a hrrummph and strode angrily away. As he was almost out the door I said to the bass player "Keep playing". I jumped from the piano, ran up to him and said "I played your f---ing tune. You talked all the way though it. Now, I'm going to play it again, and you're going to stand right here and not move until I'm finished." Looking shocked and sheepish, to say the least, he dutifully obeyed and stood there for the next eight minutes and 14 choruses while I replayed his request. Upon hearing the last chord he saluted me, took his wife on his arm and vacated the premises. I was lucky. One of these days I'll get shot.

Third story just came to mind. Shortly after I moved to New York, Ron Carter had been hearing of me and called me for a week at the Knick (they were doing five nights then, as opposed to two now). During a set, a man came up, handed Ron a $5 bill and requested a tune. Ron looked at it, handed it back and said "Sorry, that's a twenty dollar tune."

I am in Seattle to help fire the opening shot of the Earshot Jazz Festival, a discussion about the jazz audience and what might be done to expand it. I have reservations about the premise of the second part of that proposition, but I look forward to learning from my fellow panelists. Admittance is free. A cynic might say that you get what you pay for.

This massive city-wide festival includes Bill Charlap, Jason Moran, Robert Glasper, Patricia Barber, Ravi Coltrane and Luciana Souza, among dozens, maybe hundreds, of other musicians. For a schedule, go here. I wish that I could stay around for all eighteen days of it, but obligations elsewhere are calling.

The National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters for 2006 are Ray Barretto, Tony Bennett, Bob Brookmeyer, Chick Corea, Buddy DeFranco, Freddie Hubbard and John Levy. They were announced a few weeks ago and will be honored at the annual meeting of the International Association of Jazz Education in New York in January. That is not news.

This, however, may be new to you. It was to me. At the NEA web site ,you will find photographs of the new honorees. If you go there and click on each winner's photograph, you will get a comprehensive biography. It is good interactive internet entertainment and information. Then, go to this page for photos and bios of the previous NEA jazz masters. In the group shot, click on each person to link to his or her bio and another photograph. Good interactive information.

Thanks to Bruce Tater, Mark Chapman's sidekick at KETR-FM in the Dallas area, and to

An early September posting on Rifftides discussed Czech President Václav Klaus’s involvement with and support of jazz. In it, I quoted a communique from the fine Czech pianist Emil Viklický:

There is a new CD coming out from Prague Castle - George Mraz’s 60th birthday. Multisonic asked me to help with mixing and arranging things since George himself is not here in Prague. I will push Multisonic owner, Mr. Karel Vagner, to have better distribution for abroad.

That CD of a concert honoring and featuring Mraz has just been issued. The great bassist performs with four colleagues with whom he grew up in music in Czechoslovakia, decades before that nation split, peacefully, into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Viklický and Karel Ružička share piano duties. Rudolf Dašek plays guitar. Ivan Smažík, Mraz’s grade school companion from Tábor in southern Bohemia, is the drummer. These men are in the top tier of Czech jazz players who weathered communist domination of their country and culture and lived to see their nation independent after the wall came down. By then, Jiří Mraz had become George, moved to the United States and established himself as one of the best bassists in the world. Whenever he goes home, it is an occasion. He has had no grander homecoming than this concert at the Czech equivalent of the White House. Mraz is introduced and praised by the president of his native land and given a birthday party. As Jan Beránek points out in his literate, informed liner notes, it happened once before, when Richard Nixon threw a birthday celebration for Duke Ellington.

So much for the honor. How is the music? It is full of spirit, warmth and virtuosity. Except for one number, Mraz is omnipresent, playing with impeccable technique, perfect time, and feeling that radiates from his Moravian heart and blues soul. He was born in southern Bohemia, but as a boy spent his summers in Moravia and soaked up its music. Moravian music, with its predominance of minor keys, has stylistic similarites to blues. Major and minor thirds often coexist in the same Moravian songs. It is no surprise that musicians like Mraz and Viklický gravitated toward jazz. Their work together in Mraz’s CD Moravá concentrates on Moravian material melded with jazz

Mraz’s playing on the unaccompanied first number of this new album, the traditional “White Falcon, Fly,” is enough to make grown men weep, if they happen to be bassists. The rest of the program consists of standards (“For All We Know,” “My Foolish Heart,” “Rhythm-a-ning”) and compositions by Mraz, Ružička and guitarist Dašek, who was once Mraz’s bandleader. Mraz’s “Picturesque” has bass-guitar unison passages intimating that he may have had his bass predecessor Oscar Pettiford in mind when he wrote it. Mraz sits out for Thelonious Monk’s “Rhythm-a-ning,” a two-piano performance by Viklický and Ružička so marinated in jazz piano vocabulary and grammar and—well—rhythm, not to mention humor, that it suggests an album of their collaborations is not just a good idea but mandatory. Mraz mastered arco playing in his studies at the Prague Conservatory, then refined his mastery, as his bowing on his “Blues for Sarka” testifies. Ružička’s “Streamin’” melds jazz sensibility with that Moravian minor-thirds feeling, and Mraz has a stunning solo.

If you know people who feel that Europeans don’t quite have the hang of jazz, this CD would be a splendid means of convincing them otherwise. About the matter of the Multisonic label distributing abroad; I hope that it comes about. In the meantime, it is possible to order from this Czech website, which also offers MP3 samples of the music. My experience is that the Jazzport site is reliable.

Rifftides readers interested in knowing more about the great drummer and arranger Tiny Kahn (discussed in this posting) will find it in Burt Korall’s Drummin’ Men—The Heartbeat of Jazz: The Bebop Years. From Korall’s chapter on Kahn:

His drumming made bands sound better than they ever had before, particularly during his last years when he had all the elements of his style in enviable balance. His time was perfect—right down the center. He wasn’t too tense or too laid-back. Kahn had his own sound and techniques on drums and could be quite expressive, using his hands and feet in a manner that was his alone.

Musicians remember how easy his charts were to perform; they felt right for all the instruments and never failed to communicate and make a comment. His unpretentious writing mirrored his concern for expressing ideas in an economical, telling swinging manner.

Kahn’s intellectual and cultural breadth matched his physical size. The pianist Lou Levy told Korall, “He alerted me to Al Cohn and Johnny Mandel. Kahn-Cohn-Mandel became the three wise men, as far as I was concerned. Tiny also introduced me to Alban Berg and Paul Hindemith.” Korall’s book covers bop drummers from the transitional figures (Jo Jones, Sid Catlett) through the innovators (Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, Stan Levey, Shelly Manne) to the important and obscure (Ike Day). Its predecessor volume treated drumming in the swing era with similar scope, detail and insight. Both of Korall's books belong in anyone’s basic library of books about jazz.

Thanks to artsjournal.com blogmate Terry Teachout for jogging my memory about Drummin' Men.

Stan Levey was two years younger than Kahn, but in 1944, at eighteen, was Dizzy Gillespie's drummer and provided Kahn with lessons by example. Nearly a decade younger than Levey, Artt Frank was fifteen in 1948 when he frequented 52nd Street, convinced Levey that he was serious about learning to play and, for his sincerity, received instruction. Neither Levey, Kahn nor Frank had the almost supernatural technique of Max Roach, the reigning bop drum master. What they had in common was unerring time, intelligence, hearing keenly attuned to their bandmates and the flexibility to provide the contrasting rhythmic elements of steadiness and punctuation that bebop soloists needed for support and inspiration. Frank is not as well known as many modern drummers, but he is respected and admired by musicians as diverse as Dave Brubeck and Dave Liebman and has worked with a wide range of players. His longest association was with Chet Baker, who has often been quoted as saying that Frank was his favorite drummer.

Frank's book, Essentials for the Bebop Drummer, is fundamentally an instruction book for drummers, but it has other values. Among them are his anecdotal story of evolving from a poor boy growing up in a little town in Maine into a drummer encouraged by Charlie Parker; explanations of bop rhythms that laymen can understand; and a CD in which he and fellow drummer Pete Swann illustrate the lessons. The CD also has tracks of Frank demonstrating the practical application of the patterns he teaches as he performs with colleagues in the Southwest. He makes his home in Tucson. On a couple of pieces, he also sings, an activity that he evidently intends to pursue further. I find the book entertaining and helpful. I think I'll get out an old set of brushes that has been languishing in a drawer, sit down with a large piece of cardboard on my lap and see if I can master a couple of Frank's basic left hand exercises.

Where will we find new jazz writers and critics? At least one will develop his or her chops under the sponsorship of Jerry Jazz Musician. Joe Maita, the proprietor of that estimable web site, is holding a competition to choose someone fourteen to seventeen years old to become a columnist for JJM. If you are in that age group or know someone who is and might qualify, you can find details here. Writer Gary Giddins and singer Dee Dee Bridgewater will choose the winner. And may the best youth win.

The comprehensive boxed set Count Basie and his Orchestra: America’s # 1 Band (Columbia/Legacy) has been out for a couple of years during which I have played it so often that if it was on vinyl LPs, I’d have worn them out. Its four CDs contain the most important Columbia recordings of the Basie band from late 1936 through the end of 1940. It was some of the most influential music of the period—indeed, of any period. Lester Young’s other-worldly tenor saxophone solos were one reason (in the notes, Sonny Rollins is quoted as wondering what planet Young appeared from).

There were plenty of other reasons: the ball-bearing propulsion of the celebrated all-American rhythm section, Harry Edison’s eliptical trumpet solos, Buck Clayton’s glittering ones, the speaking-laughing trombone solos of Dickie Wells, the spare perfection of Basie’s piano interjections, spare arrangements that swung off the paper or out of the collective heads of the band.

The set also has a selection of superior Basie tracks made after Young left the band in December of 1940, through the spring of 1951, when bebop had changed the landscape and the big band era had declined but not quite fallen. In the last of them, the band had important transitional swing-to-bop players, among them tenor saxophonists Wardell Gray and Lucky Thompson and trumpeter Clark Terry. The book of arrangements had works by Dizzy Gillespie, Tadd Dameron and Neal Hefti, hinting at Basie’s coming transition from the loose, swinging outfit he had led for twenty years to a machine-tooled juggernaut oriented more toward arrangers than soloists.

All of the music on the first three CDs in the set has been previously issued to a faretheewell, though never before in so comprehensive a fashion or with such clear sound. What makes the box indispensable is the inclusion of a fourth CD of previously unavailable air checks of the 1939-1941 band in broadcasts from the Famous Door, the Savoy Ballroom, the Meadowbrook Lounge and the Café Society Uptown. To hear the Basieites playing in their workaday world for audiences that came to dance and listen is a revelation. The radio microphones captured an element that virtually never exists in a studio, the human connection between performers and their audience. There is a sense that, sixty-five years apart, we and the musicians and those appreciative audiences are sharing the same space. The soloists are not necessarily playing better than they did in the studio, although the solos are full of surprises simply because they are different from the ones on the same tunes in the studio versions. But the sense of their engagement is palpable. There is lots of “new” Lester Young, and lots of young Harry Edison telling silver truths through his muted horn, and there are rides on carpets of rhythm launched by Basie, Freddie Green, Walter Page and Jo Jones.

There is someone else: Billie Holiday. She sang with Basie for a year, but had a contract with a different record company and was not allowed to record with him. Three 1937 pieces from the air checks let us, at last, understand why so many people who heard her with Basie have written and talked about it as the ultimate Holiday experience. Her use of rhythm, her time sense, allows her to float above the ensemble much as Young did, taking the same kinds of chances with phrasing, stretching without effort across the bar lines. She has transformed her Louis Armstrong inspiration into a marvel of individual artistry. Her way with lyrics is unlike that of any singer at the time other than Armstrong's. My guess is that her example had a profound effect on Bing Crosby, who was the country’s star vocalist when she emerged.

If you want to know who was influencing the young Frank Sinatra, if you have any doubt where Peggy Lee came from, listen to Holiday on “I Can’t Get Started” and “They Can’t Take That Away From Me.” Hear her turn the silly “Swing, Brother, Swing” into a triumph. The delightful Helen Humes does some of her best singing with Basie on these air checks, but Billie Holiday is transcendent.

Responding to the Rifftides posting about La Scena Musicale, Paul Conley of KXJZ in Sacramento, California, led us to his colleague Jeff Hudson's interview with the mezzo soprano Cecilia Bartoli. This site has Hudson's short and longer interviews with Bartoli and excerpts of her singing. Many jazz musicians and listeners are put off by opera, but the range, purity, power and sheer beauty of Bartoli's voice may make a convert or two.

Speaking of being led, here's a double lead. On the home page of the Bill Evans website, I found a link to a blog about classical music that has an erudite, informed posting about Evans. Among other interesting facts about the great pianist, the anonymous author of the blog called On An Overgrown Path discloses that Evans influenced the modernist composer Gyorgy Ligeti as Ligeti was creating his Etudes for solo piano. Further exploration of the site turned up valuable pieces on Messiaen, Beethoven and one of my favorite Swedish pianists, Jan Johansson, among many other musicians. I'm making On An Overgrown Path a habit and adding it to the Other Places list in the right-hand column.

Happy birthday to one of my favorite fellow bloggers, DevraDoWrite, who reports that it's going to be more or less business as usual today. But there is nothing usual about her business, which, at the moment, includes writing a biography of Luther Henderson, an underheralded figure in twentieth century music.

And now, a visit from the lovely and popular Mea Culpa.

Please disregard the arranger credits contained in this posting of two days ago. Johnny Mandel did not arrange “TNT,” “Blue Room,” “Who Fard That Shot?,” “My Heart Stood Still” and “Jeepers Creepers.” After faithful reader Russell Chase cast doubt on my assertion that the charts were Mandel's, I asked Fantasy's Terri Hinte for a copy of the reissue CD. When it arrived, I found that in the original liner notes, George T. Simon wrote that the arrangements were by Tiny Kahn. In a telephone conversation, Mandel confirmed it. He and Kahn were friends from the time they were both fifteen years old, growing up in New York City. Mandel went on at length about his admiration for Kahn, who was a rarity, one of the few drummers in jazz who was also a gifted composer and arranger.

"In fact, I don't know of any others at the time, except for Louis Bellson," he said. "I loved Tiny Kahn."

Kahn, who was not tiny, died of a massive heart attack in 1953, when he was twenty-nine years old. He had worked in the big bands of Herbie Fields, Georgie Auld, Boyd Raeburn, Woody Herman, Chubby Jackson and Charlie Barnet and was the drummer in a brilliant Stan Getz quintet that also featured guitarist Jimmy Raney and pianist Al Haig. His discography is enormous for a man who died so young.

When arrangers gather, they discuss Kahn as a peer of and influence on Mandel, Al Cohn and Gerry Mulligan. "He was a truly great musician and a very funny man," Mandel told me. "I think he would have been the best of us all, if he had lived, and if he wasn't working as a standup comic."

There are three verified Mandel arrangements in the the Elliott Lawrence CD in question. They are "Tenderly," "Moten Swing" and his adaptation of the Noro Morales arrangement of "Ponce."

Persistance and dumb luck have solved the computer conundrum that derailed Rifftides for a couple of days. Thanks for your forebearance. You did forebear, didn't you? At any rate, we're back on the tracks.

Marc Chénard, the jazz editor of La Scena Musicale, sent me his review of Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond, thus acquainting me for the first time with an impressive Canadian magazine. La Scena Musicale publishes a relatively new English edition,The Music Scene, as well as its established French version. The Fall 2005 issue includes not only Chénard’s book review, but also his interesting piece contrasting the careers of Sonny Rollins and Ornette Coleman.

Rollins, one of the rare surviving masters of the bop and hard-bop eras, is a champion of the great American song book tradition, a veritable walking fakebook of evergreens and jazz standards composed by other greats like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, as well as a few of his own (“Oleo,” “Valse Hot” and the pernnial jazz calypso “St Thomas”). Ornette Coleman, conversely, was thrust on the scene amid controversy, heralded as the instigator of “Free jazz,” a term that until it appearance in the late 1950s meant “music with no cover charge.”

The bulk of the magazine deals with classical music. The cover story is a verbatim interview with the mezzo soprano Cecilia Bartoli. The Q&A transcription format is lazy journalism, in lieu of writing. For the most part, the mezzo soprano Cecilia Bartoli gives predictable answers to softball questions, but she does offer an insight into the technical challenge a mezzo faces in roles not written with her kind of voice in mind.

CB: If you look in the original score of Don Giovanni or Nozze di Figaro, Mozart wrote those roles for sopranos; mezzos didn’t exist as a category. For Elvira, you need a flexible voice, but also with a nice, warm color in the middle. Fiordligli has to sing the difficult “Come scoglio”; you need the range up to a high C. But in Act 2, you have this incredible “per pietá,” whilch is really a masterpiece. It is written in the low register, so if you are a lyric soprano, it is good for the first aria but not the second. I sing a role that suits my instrument. In Mozart, it is clear you need once voice for Elvira, and a different one for the Queen of the Night—and I am not planning to sing Queen of the Night! (laughs)

I was taken with the critic Norman Lebrecht’s column about the rise and possible fall of the child soprano Charlotte Church, now nineteen. He compared the pressures on her with those on other child stars, including Judy Garland, Michael Jackson, Yehudi Menuhin, Evgeny Kissin, Mozart, Nadia Comaneci ”and any chess master you care to name.”

As much as the voice, Charlotte's attraction was her naturalness, her determination to stay close to roots and friends in Cardiff, her sense of mischief. The grim-faced gutter press made a fetish of her frolics, anointing her Rear of the Year at 16, and dogging her dalliances with boys and drink. Charlotte played along with the pack, relishing the sales potential of celebrity, disporting herself on a beach lounger for the benefit of long lenses. She went on-line at the tabloid Sun to discuss ex-boyfriends with its prurient readers. She had the illusion of being in control and, at 19, the world at her feet. Who could begrudge that?

But listen to the single and the smile fades. Taken from her first pop album, Tissues and Issues - her previous CDs were, by some stretch of corporate imagination, designated Classical – "Call My Name" is an unremarkable heavy pounder and the delivery is commendably energetic. The voice, however, has deepened and coarsened, gritting around in a low-alto register and lacking stamina for the longer phrase. Too many fags, too much booze, perhaps. At this rate, there won't be enough left in the box to sing “Goodnight Irene” when she's thirty. As for that tremulous vibrato, it has turned into a nasty old wobble much in need of remedial tuition.

Nice uses of alliteration in that first paragraph, hard to do without being a cornball. La Scena Musicale and The Music Scene are well worth a look. You can find them in PDF form by going here.

For two days, indispensable functions of my computer have been performing erratically, requiring constant attention and consuming so much of my time and thought that further postings are going to have to wait. I trust that denizens of the digital world will understand. See you soon, I hope.

Not that we're trying to be Johnny Mandel completists, but Rifftides reader Russell Chase wrote to remind me of the 1956 Fantasy LP Elliot Lawrence Plays Tiny Kahn and Johnny Mandel Arrangements. Terri Hinte of Fantasy discloses that the music in that album is now included in an OJC CD titled The Elliot Lawrence Big Band Swings Cohn & Kahn. Why Mandel didn’t make it into the title this time around is unclear (one syllable too many?), but five of the arrangements are his, “TNT,” “Blue Room,” “Who Fard That Shot?,” “My Heart Stood Still” and “Jeepers Creepers,” all Mandel in his big band arranging prime.

Al Cohn and Zoot Sims were in the band, well known and headed toward outright fame. Others members: Urbie Green, Hal McKusick, Nick Travis and Eddie Bert, along with the splendid bass-and-drums team of Buddy Clark and Sol Gubin supporting Lawrence, a more than capable pianist. This may have been the best of Lawrence’s several excellent bands. Mandel, Cohn and Kahn had a sterling collection of players to write for. The musicians gave the arrangements spirited readings. Recommended.

In the weekend edition of The Wall Street Journal, artsjournal.com’s commander in chief, Doug McLennan, asked serious questions about the viability of the nonprofit business model for arts organizations—questions that will resonate with many jazz societies, and not just the big ones.

What to do? Many nonprofits are already playing with a for-profit mentality, coyly stepping up to the line separating it from nonprofit practice -- sometimes even stepping over it while hoping nobody notices. Major museums mount fashion exhibitions that are sponsored by industry players. Public TV and radio run promo spots that they call "underwriting" rather than the "ads" that they are. Boston's Museum of Fine Arts rents out its collection to a Las Vegas casino.

Don't expect institutions like MoMA or the Los Angeles Philharmonic to announce an IPO anytime soon. But increasingly, for many arts groups, the nonprofit model has become a straitjacket, one they are struggling to escape. The scale of for-profit behavior by many nonprofit arts organizations today wouldn't have been allowed 20 years ago. Yet even stretching traditional nonprofit status to the point of breaking, the current model looks unsustainable, both financially and artistically.

I can’t link you to the piece. If you subscribe to the WSJ online edition, you can go to the paper’s web site and search for “Culture Clash.” If you are not a WSJ reader, you could look it up at the lilbrary.

library (liۢ brerۢ ē) n., pl. -brar·ies 1. a place set apart to contain books, periodicals, and other material for reading, viewing, listening, study, or reference, as a room, set of rooms, or building where books may be read or borrowed.—Random House Dictionary of the English Language(In case, in this electronic world, you’ve forgotten.)

Artsjournal.com is the umbrella organization under which Rifftides flourishes. Well, under which we exist. The Rifftides staff recommends that you visit artsjournal.com for a compilation of news from the wider arts world. We check it out every day.

NOTICE TO RIFFTIDES READERS: THIS ITEM IS UPDATED WITH INFORMATION ADDED SINCE THE ORIGINAL POSTING.

A Rifftides reader asks:

Can you point us to recordings of the Mandel arrangements you mentioned in your recent posting? (I'm having trouble locating “TNT”, “Keester Parade” and some of the others.)

With pleasure. I’ll give you sources for those and others. Click on the blue links to find the CDs.

Not his earliest, but some of Mandel’s best compositions and arrangements of the forties were for Artie Shaw’s superb—and short-lived—bebop band. “Krazy Kat” and “Innuendo” are in Artie Shaw and His Orchestra 1949 (Music Masters), along with Mandel’s arrangement of “I Get a Kick Out of You.”

His arrangement of Count Basie's “Low Life” is on Count Basie: Low Life (Jazz Club). "Low Life" is also in the Mosaic boxed set The Complete Clef/Verve Count Basie Fifties Studio Recordings, as is Mandel's "Straight Life."

“Not Really the Blues” is part of a Capitol Woody Herman compilation, Keeper of the Flame. Mandel once told me that Herman recorded the piece at a slower tempo than he had in mind. Mandel kicked it off considerably more briskly the other night in his JWC3 concert. Nonetheless, Herman’s is a great performance of a brilliant arrangement. The musicians in Herman’s Third Herd (mid-1950s) loved the chart so much that they often prevailed on the old man to play it two or three times a night. Later in the fifties, Herman recorded Mandel's "Sinbad the Sailor" for the Everest label. If you buy the most recent reissue that contains "Sinbad," the CD called Herman's Heat & Puente's Beat, be aware that the music is wonderful, but the album is a discographical mess; titles don't match the tracks. "Sinbad" is listed as track 17. It is, in fact, track 13. Track 17 is Neal Hefti's "The Good Earth."

“Keester Parade,” “TNT” and “Groover Wailin’” are on Cy Touff, His Octet & Quintet (Pacific Jazz), one of the best albums by any medium-sized band. It is neck and neck in the Mandel sweepstakes with his arrangements in Hoagy Sings Carmichael (Pacific Jazz), a showcase not only for Carmichael but also for the alto saxophonist Art Pepper. The Touff session personnel included trumpeter Harry Edison, who was so impressed with “Keester Parade” that he later borrowed (ahem) Mandel’s melody and called it “Centerpiece.”

Also in the fifties, Mandel made arrangements of “Stella by Starlight” and his composition “Tommyhawk” for a Chet Baker sextet that included valve trombonist Bob Brookmeyer, and Bud Shank playing Baritone saxophone. They are in an album called Chet Baker Big Band (Pacific Jazz), in which the biggest band has eleven pieces. A master of writing for strings, some of Mandel’s earliest and loveliest work in that idiom was also for Baker—arrangements of “You Don’t Know What Love Is,” “Love,” “I Love You” and “The Wind” in Chet Baker & Strings (Columbia). Mandel’s score of the 1958 film I Want To Live is on the movie soundtrack recording. The motion picture is available on DVD. He wrote superb arrangements of “Black Nightgown” and “Barbara’s Theme” for Gerry Mulligan’s Concert Jazz Band (Mosaic) in the 1960s.

Mandel’s later career as a song writer and composer-arranger for motion pictures and television grew out of his years of writing for jazz groups. The pieces mentioned are remarkably fresh and undated.

In the Rifftides posting about Joe Locke, I used poetic license in suggesting that without electricity the vibraharp, or vibraphone, amounts to a metallic marimba. Two readers who know what they’re talking about make it clear that my poetic license should not be renewed. The first is Charlie Shoemake, a veteran vibist of more than forty years admired for, among other things, his mastery of harmony and his ability to play with speed approaching that of light.

Sorry to correct you but Red Norvo,Gary Burton, and I do not use the vibraphone with electricity. In other words: no motor. I don't know Red’s or Gary’s reason, but in my case it was my years with George Shearing. When I first joined him he said that for his famous ensemble sound, he wanted the vibes played with no motor but that I could turn it on when I took a solo. Sometime during my seven year hitch I just forgot to turn it on—permanently. The result was that I was now a Charlie Parker/Bud Powell-inspired vibes player with a different sound than Milt Jackson’s because of no motor, and a different sounding vibes player than Gary Burton and his students (Dave Samuels/Dave Freidman) because of the different musical content.

That's the jazz vibraphone instruction 101 for today.

Not quite. Now comes Gary Walters, a jazz pianist who teaches music at Butler University in Indianapolis.

For the first time, I felt compelled to write after your comments discussing electric vs. acoustic instruments. You had me until you suggested that a vibraphone without electricity was a marimba. I'm sure you know it's not quite that simplistic. A vibraphone has bars made of soft metal alloys and a good marimba has bars made from rosewood or other extremely dense woods. That, combined with the appropriate length of resonator tube, creates a warm, woody sound that I think is beautiful and distinct from the warm, soft metal sound produced by a vibraphone with its motor turned off. Many great vibraphonists that you can name as easily as I play with the motor either on or off because it adds another texture to their means of expression. But the marimba, with a soft mallet—every bit as warm and "woody" as the "real" bass you favor!

Thank you for allowing me to clarify and please, keep up the great writing!

I promise never to oversimplify again.

Of course, that’s an oversimplification.

It is well that there is no one without a fault; for he would not have a friend in the world.

—William Hazlitt

I'm heading home after a Southern California week split between Jazz West Coast 3 and decompressing. The Santa Ana winds came back and it was 72 degrees at the beach at 10 o'clock last night. Somehow, I don't think it will be that way in the Pacific Northwest.

It is unlikely that I will post again today. Remember, please, that the Rifftides staff is always glad to hear from you. The e-mail address is in the right-hand column.

The final session at the L.A. Jazz Institute’s Jazz West Coast 3 festival was an event so rare that musicians and attendees were buzzing about it from the moment they arrived. It was the appearance of Johnny Mandel leading a big band in a concert of his compositions and arrangements. Mandel has been a hero of musicians since the late forties, more than fifteen years before “The Shadow of Your Smile,” “Emily” and other pieces made him one of the few writers of quality songs to become a popular success in the second half of the twentieth century.

Although he was being honored as a legend of the west, Mandel’s fame is worldwide. His jazz charts for Artie Shaw, Count Basie, Woody Herman, Maynard Ferguson, Chet Baker, Hoagy Carmichael, Buddy Rich and Gerry Mulligan are imperishable goods, gems of the repertoire. With Mulligan, Bill Holman, Thad Jones, Neal Hefti, Gerald Wilson, Bob Brookmeyer and Al Cohn, he is one of the icons of jazz writing in the fifties, perhaps the last golden age of that demanding craft. His scoring for films and his arranging for singers (Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Peggy Lee, Shirley Horn, Anita O'Day, Mel Torme, Andy Williams, Natalie Cole, Diana Krall) constitute a gold standard for the field. His oldest works are as fresh as this morning.

Leading a band of seventeen hand-picked musicians, Mandel gave the audience “Keester Parade,” “Low Life,” three pieces from his score for the motion picture “I Want To Live, his famous arrangement of Tiny Kahn’s “TNT,” “Not Really the Blues,” the theme from M*A*S*H* and Kim Richmond’s kaleidoscopic treatment of Mandel’s “Seascape.” There were also performances of “Emily” and “The Shadow of Your Smile” and guest appearances by Pinky Winters and Bob Efford. Ms. Winters sang Dave Frishberg’s lyrics to Mandel’s “You Are There,” accompanied by only the composer at the piano. Together, without embellishment, they created magic, something at which this masterly singer has excelled for many years to recognition that comes nowhere near her level of artistry. Efford, best known as a baritone saxophonist, played the clarinet roles of Artie Shaw and Woody Herman in Mandel arrangements.

It was obvious that each member of the band was thrilled and flattered to be asked to play for Mandel. Collectively and as soloists, they performed at a fine edge of inspiration. Under his minimal but firm conducting, the horn sections were perfection in their reproduction of the unity, dynamics and rhythmic jazz essences of the writing. As for soloists, singling out a few would be to ignore the rest without justification. The players are listed below.

At seventy-nine, Mandel is a slight man with a low voice and a calm manner. He speaks quietly and regards a conversation partner with frank interest. Directing the band, he sometimes turns and watches the audience with the same intense curiosity. One of the most successful and admired musicians of his time, he exhibits no smidgen of ego. “The thing about John,” one of his friends said, “Is that he doesn’t know he’s Johnny Mandel. He thinks he’s just one of the guys.” The guys may think that, too, but they revere Mandel. They play for him with love, enthusiasm and no reservations of the kind that sidemen often have about leaders. He has that in common with Holman. I have never heard a player utter a disrespectful remark about either.

Mandel found the Jazz West Coast 3 experience rewarding enough that he is thinking of getting a book of arrangements together, organizing a band and playing a few gigs. That would be something to look forward to.

The band playing the compositions and arrangements of Johnny Mandel, October 2, 2005:

Reeds: Kim Richmond, Lanny Morgan, Tom Peterson, Doug Webb, Bob Carr

Trombones: Dave Ryan, Andy Martin, Scott Whitfield, Bryant Byers

Trumpets: Roger Ingram, Bobby Shew, Carl Saunders, Ron Stout

Piano: Bill Mays

Bass: Chris Conner

Guitar: John Pisano

Drums: Kevin Kanner

Guests: Bob Efford, clarinet; Pinky Winters, vocal

Eleven years after the first of impresario Ken Poston’s Jazz West Coast extravaganzas, I spent the weekend at the Los Angeles Jazz Institute’s Jazz West Coast 3, subtitled Legends Of The West. The attendees were fewer and grayer than eleven years ago. The music to which they remain devoted was consistently good and, at its best, splendid and undated. I spent part of the time preparing for a reading, panel and book signing and was unable to hear all of the four days of music, but took in as much as possible.

I arrived Friday evening in time for an all-star tribute to Bud Shank, an alto saxophone mainstay of west coast jazz in its heyday of the 1950s who survives as a fiery grand old man of the instrument. Following the tribute, Shank took command of a hard-driving rhythm section of pianist Bill Mays, bassist Chris Conner and drummer Joe LaBarbera. In the decade or more since he gave up the flute to concentrate on alto, Shank has become increasingly expressive, even rambunctious. He stayed true to his latterday form in several apperances during the weekend. His stylistic flute successor, Holly Hoffman, approximates Shank’s admired tonal qualities, swings hard and improvises lovely melodies, as she did to great effect in the tribute.

Herb Geller, Shank’s alto sax contemporary, traveled from his home in Germany for the event. He played a set of his compositions that included pieces from his unproduced musicals, Playing Jazz and another based on the life of the 1920s entertainer Josephine Baker. Geller’s songs for the theater have dramatic content appropriate to the idiom and translate beautifully for improvisation. He and Mays played for and off one another with elan, hard swing and humor. Mays was, hands down, winner of the event’s iron man competition, playing piano in five bands, wowing the audience with his energy, creativity and—not at all incidentally—sight-reading in situations in which he was a last-minute recruit.

Two recreated bands that looked on paper as if they might be exercises in nostalgia had surprising vitality. I thought when I heard it decades ago that the recorded music of the French horn player John Graas was stodgy and pretentious, but an octet headed by a Graas successor, Richard Todd, performed a delightful hour of Graas’s compositions and arrangements. Maybe I was missing something the first time around or—as I suspect—Todd and his colleagues booted the arrangements into rhythmic life.

In the fifties, Allyn Ferguson’s Chamber Jazz Sextet created a following for its ingenious incorporation into a jazz ensemble of classical forms and techniques . At JWC 3, the 2005 version of the band—reinforced to an octet—gave a program in which harmonic depth and textures buoyed arrangements that had swing and humor. I was particularly taken with Ferguson’s fifty-year-old variations on 250-year-old dance movements from J.S. Bach’s secular chamber works.

The eighty-four-year-old drummer Chico Hamilton looks and carries himself like a man twenty years younger. In a panel discussion, he spoke expressively about his fifties quintet, noted for combining delicately balanced instrumentation and tonal qualities with blues feeling and exploratory improvisation. Later, he performed with his current quintet, eschewing his celebrated brushwork dynamics in favor of sticks, drumming with nearly military precision. His band’s performance verged on rhythm and blues and often entered it entirely.

The saxophonist, actor and wry humorist Med Flory presented a big band session of the kind he has led since the early fifties. The genius of Flory’s self-deprecatory leadership lies in creating the impression of flying by the seat of his pants, barely holding the band together, but almost invariably getting it to swing amiably. He provided plenty of solo space for his sidemen, which gave trombonists Andy Martin and Scott Whitfield, trumpeters Bob Summers and Ron Sout, saxophonists Lanny Morgan, Doug Webb and Jerry Pinter and pianist John Campbell opportunities to shine. Like all Flory perfomances, this one melded entertainment with serious music, to the enhancement of both.

I’ve been up too late too many nights in a row, listening and hanging out, a satisfying facet of these gatherings. It’s time to catch up on missed bedtime hours, lulled to sleep by the Malibu surf rolling onto the beach outside the gracious house in which I am fortunate to be a guest. I’ll have a final Jazz West Coast 3 report tomorrow. It concerns a legend of the west, east, midwest, south and north.

The energetic, and possibly sleepless, Washington, DC trombonist, singer and bandleader Eric Felten writes:

I read the Fud Livingston post with interest, because in my endless searches for vintage big band music I have acquired a number of Fud Livingston charts. But I can't remember ever actually trying any of them out. In part, that's because they are "stocks" (which I'm happy to collect, but wouldn't go out of my way to perform). And as much as I hate to admit it, I think I have reflexively dismissed the charts because of the man's rather goofy name. Shallow of me, but human. And not without some grounding in reason -- one learns not to expect hot music from the Ish Kabibbles of the world. But now I'll go check my library to see if there is something from Fud worth putting in front of the band.

I also enjoyed the trolley item, in no small part because I live one house away from what used to be the trolley car tracks in my Washington neighborhood. It was the line that ran up along the Potomac, ending in Glen Echo Maryland, where there is an historic amusement park built long ago by the trolley company. The business model worked like this: Build an amusement park at the end of the trolley line, and you could take the trolley system's largely unused weekend electricity and use it to power the rides. Getting to the park also gave people a reason to ride the trolley on the weekends. Sadly, the trolley was killed off about 1980. But the amusement park is going strong. The only ride left is a gorgeous 1920s Denzel carousel to which my kids (and I ) are devoted. The bumper car pavillion has been turned into an open-air dance space. Other buildings have been turned into art studios, a puppet theater and a children's theater.

But the most extraordinary thing at the park is the Spanish Ballroom. Built in the 1930s it has been beautifully restored and it continues to host a remarkably vibrant dance scene. Saturday nights are for the swing dance crowd, but other nights of the week host tango, contra, waltz etc. I was there with my big band in August, and we played for about 600 very sweaty dancers. (For authenticity's sake, air-conditioning was never installed in the ballroom.) It's great fun playing for dancers -- the rhythm takes on a whole new meaning. And when we play for dances, part of the fun is the feeling that we're keeping a neglected part of the jazz tradition alive.

It is good to know that this splendid remnant of the American past exists. Most such dance pavilions faded away with the passing of two other great American institutions, the swing era and urban rail transporation.

Old friend Bob Godfrey, retired drummer and retail record entrepeneur, was prompted by Freddie Schreiber's silly names to observe:

You may have opened up a can of worms.

Then, he proves it.

Todd L. Entown

Wynn Abaygo

Rick O'Shay

Dick Tatorial

Unretired vibraharpist and concert entrepeneur Charlie Shoemake offers:

Otto Nowhere

Hey, I don't write these things; I just pass 'em along.

QUOTE

Those rugged names to our like mouths grow sleek—Milton

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Rebuilding Gulf Culture after Katrina

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books