Rifftides: October 2010 Archives

Mark Stryker, music critic of the Detroit Free Press, sent this note:

Thought you might be interested in this— a couple months ago I recall a comment on your Mitch Miller/Bird post including a reference to the Australian Jazz Quartet/Quintet. The vibraphonist from the group, Jack Brokensha, a longtime Detroiter,died this week at 84. This is a link to the Free Press obituary.

Couldn't find any YouTube clips with Jack, save a few Motown hits where he's playing various percussion instruments and/or vibes. There must be film of the band somewhere; I can't imagine they weren't on television at some point, particularly when they went back to Australia to play. Interestingly, Jack once showed me a fascinating reel of home movies that he had taken back in the middle '50s when the AJQ was traveling widely as part of package tours with Miles Davis's band, Brubeck, Carmen McRae and others. The films were super 8 and they were silent. What stays with me 14 years later is that you saw all the cats relaxed on tour, waiting for the bus, hanging on the street, smiling for the camera (Miles too), plus film of the marquees and clubs in various cities. My memory is hazy but I think he also had film of the various groups performing though the reason this doesn't stick out is that, as I said, it was all silent footage.Brokensha was a sweet guy with a firecracker personality. He was a real fixture here.

A year ago almost to the day, a Rifftides post called "The Art Of Art Farmer" featured three videos from Farmer's 1982 concert at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. It also had some of my musings on the great trumpeter and flugelhornist. Two of the videos were later disabled by those mysterious internet forces always patrolling in search of clips to take down for real or imagined violations. Recently, other forces—equally mysterious—restored the clips to YouTube, and now they are back in that piece in the archive. Further along, I'll give you the link to it.

BUT FIRST: In the course of reconstructing the post, I came across a little something extra or, as they say in South Louisiana, lagniappe. It is still another performance from the Smithsonian by Farmer, pianist Fred Hersch, bassist Dennis Irwin and drummer Billy Hart. Introducing it, Farmer refers to the last number in that 2009 post.

Now, go here for the reconstituted entry from October 27, 2009 and more music by a remarkable quartet.

Gail Pettis is an orthodontist turned singer (you may supply your own puns) who has commanded considerable notice in her brief new career. She has won awards, toured in Europe and Japan and recorded two albums praised by critics, including this one.

Pettis's warmth and intelligence translate into performances that put the song first. She employs her jazz time and phrasing as interpretive tools, not means of calling attention to herself. When she scats, she does it judiciously, with musical values. Here's a fine example from a television performance of Artie Shaw's "Moonray." The pianist is her frequent accompanist Randy Halberstadt, whose left hand finds intriguing harmonies.The introducer is Nancy Guppy of the Seattle Channel's In Studio series.

For Rifftides reviews of Pettis's CDs, go here and here. For more about her, go to her web site.

By any assessment, jazz in the 21st century is a minority music. Depending on whose statistics are accurate, it accounts for somewhere between 1% and 3% of record sales, right in there with string quartets and Gregorian chants. Some of the music's best American players find that they are in greater demand in Europe and Japan than in the United States, although I hear from musicians that gigs are harder to find everywhere as the world economy struggles for equilibrium and recovery.

Once in a while, a young jazz artist manages to break through to audiences who ordinarily prefer music that requires less attention. One attracting considerable notice without dumbing down is the bassist, composer and singer Esperanza Spalding, recently the subject of this Rifftides recommendation. On The News Hour on PBS last night, Jeffrey Brown reported on Spalding.

Last night, millions of Americans watched the San Francisco Giants submerge the Texas Rangers in game one of the World Series. They also saw Tony Bennett sing—of course—"I Left My Heart in San Francisco" and at the 7th inning stretch, "God Bless America." If you missed it or if you are in a part of the world mystified by the United States' baseball craziness at Series time, you may nonetheless enjoy Mr. Bennett's performance of the Irving Berlin song that many musicians and many more ordinary citizens have suggested should be the US national anthem. If you have doubts about how his 84-year-old chops are holding up, listen to Bennett leap up an interval of a seventh to the concluding A.

Note added November 1: Major League Baseball has blocked the Bennett clip. To see a fan's video from the stadium, go here. It's the best we can do until MLB unblocks the quality version.—DR

Jazz maven and senior news producer Paul Conley at Capitol Public Radio in Sacramento sent the link to that clip. The Rifftides staff thanks Mr. Conley.

As a former San Franciscan, all I can add is, Go Giants!

Some of the best new work of prominent American jazz artists is not on US labels, and not all of it is easy to find. Stars is a case in point. The pianist in the band known as the December 2nd Quartet is Dena DeRose, who sings on several tracks of this charming album. Bassist Ray Drummond and drummer Akira Tana, complete the rhythm section. The rising young trumpeter Dominick Farinacci is the fourth member. Benny Green is guest pianist on four of the 11 tracks. Recorded in California by the Vega label for the Japanese market, the album is available in the US as a pricey import unlikely to reach a wide audience. Still, connoisseurs have created a buzz about it.

The rising young trumpeter Dominick Farinacci is the fourth member. Benny Green is guest pianist on four of the 11 tracks. Recorded in California by the Vega label for the Japanese market, the album is available in the US as a pricey import unlikely to reach a wide audience. Still, connoisseurs have created a buzz about it.

The "stars" theme is hardly new, but it has rarely been pursued with more lyricism. DeRose's piano solos, pure delivery of lyrics and unison piano-vocalise improvisations are among the pleasures in jazz these days. Her work here is on the high level she has established with her recent CDs for MaxJazz, her earlier ones for Sharp Nine, a stunning one-off duo collaboration with trumpeter Marvin Stamm and her hard-to-get first album with the December 2nd Quartet. DeRose's treatment of "A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes" could revive that barely-remembered song from the old Disney cartoon feature  "Cinderella." The veterans Drummond and Tana meld smoothly with DeRose and with Farrinacci, whose intriguing freshness of conception is set on a foundation that indicates close study of Blue Mitchell, Clifford Brown and Miles Davis. His duet with Benny Green on "Stardust" consists of Hoagy Carmichael's melody with slight—but most effective—variations, a cadenza inspired by Brown and, throughout, a magic carpet of chords from Green. Green is on piano as DeRose sings and Farinacci solos on Fred Hersch and Norma Winstone's "Stars," a song that, despite its challenging intervals, could become a new standard.

"Cinderella." The veterans Drummond and Tana meld smoothly with DeRose and with Farrinacci, whose intriguing freshness of conception is set on a foundation that indicates close study of Blue Mitchell, Clifford Brown and Miles Davis. His duet with Benny Green on "Stardust" consists of Hoagy Carmichael's melody with slight—but most effective—variations, a cadenza inspired by Brown and, throughout, a magic carpet of chords from Green. Green is on piano as DeRose sings and Farinacci solos on Fred Hersch and Norma Winstone's "Stars," a song that, despite its challenging intervals, could become a new standard.

Tana's brushes accenting Bill Evans' "Turn Out the Stars" set off Farinacci's beautifully intoned delivery of the melody. DeRose's solo maintains the grave, stately spirit of the piece. When Farinacci reenters, she is as much a duet partner with the trumpeter as an accompanist. The British singer Corinne Bailey Rae's "Like a Star" lightens the atmosphere, DeRose giving the lyrics the dignity of straightforward interpretation. In solo and obbligato, Farinacci blows into a Harmon mute and DeRose executes a passage of her parallel piano-voice inventiveness. Her vocal on "Stars Fell on Alabama" is a highlight, matched by a Farinacci solo paying humorous tribute to Clark Terry and Sweets Edison. DeRose singing and Green accompanying her perform a classic version of "When You Wish Upon a Star."

and obbligato, Farinacci blows into a Harmon mute and DeRose executes a passage of her parallel piano-voice inventiveness. Her vocal on "Stars Fell on Alabama" is a highlight, matched by a Farinacci solo paying humorous tribute to Clark Terry and Sweets Edison. DeRose singing and Green accompanying her perform a classic version of "When You Wish Upon a Star."

Through "Stairway to the Stars," "Star Eyes," and a couple of songs outside the stars theme—"I Wished on the Moon" and "What Are You Doing the Rest of Your Life?"—the December 2nd Quartet offers a relaxed program packed with musical substance. Too bad it has limited distribution outside Japan, but the CD is worth seeking out for superior performances by everyone involved.

My biography of Paul Desmond includes Desmond solos that Bill Mays, Bud Shank, Brent Jensen, Gary Foster and Paul Cohen transcribed for the book. They analyze or comment on the solos and John Handy analyzes Cohen's transcription of "Take Five." In the text I suggest that playing the recordings and following along with Desmond would help readers appreciate his creative process in improvising. Even if their music-reading skills were slight or nonexistent, a general impression of the flow of notes could be enlightening.

A few readers let me know that they tried, but the transcriptions were Greek to them. Many more who accepted the challenge reported that they enjoyed the exercise and learned from it. In the unlikely event that Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond ever becomes an e-book, maybe digital technology will have advanced enough that we can find a way to marry the recordings with the transcriptions.

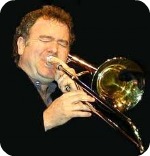

How might that work? Let's watch and listen to a video of the Los Angeles trombonist Bob McChesney. He is noted  for his playing in film, television and recording studios with everyone from Kenny G to Ray Charles, and for his jazz solos with Bill Holman, Woody Herman, Frank Capp and Jack Sheldon, among dozens of others. McChesney is a splendid soloist and a fearsome technician. Here, he harmonizes and overdubs four trombone parts in his arrangement of Cole Porter's "I Love You." Kevin Axt and Dick Weller, the only other musicians involved, accompany him on bass and drums. The transcription unfolds in synchronization with the music. Whether you can read the notes or are merely going with the flow, keep your eyes on the screen because this goes by fast. It's easier if you watch in the full screen mode.

for his playing in film, television and recording studios with everyone from Kenny G to Ray Charles, and for his jazz solos with Bill Holman, Woody Herman, Frank Capp and Jack Sheldon, among dozens of others. McChesney is a splendid soloist and a fearsome technician. Here, he harmonizes and overdubs four trombone parts in his arrangement of Cole Porter's "I Love You." Kevin Axt and Dick Weller, the only other musicians involved, accompany him on bass and drums. The transcription unfolds in synchronization with the music. Whether you can read the notes or are merely going with the flow, keep your eyes on the screen because this goes by fast. It's easier if you watch in the full screen mode.

Have a nice weekend.

Trombone players are generally the nicest brass players. However, they do tend to drink quite heavily and perhaps don't shine the brightest headlights on the highway, but they wouldn't hurt you and are the folks to call with all your pharmaceutical questions...It's a little-known fact that trombone players are unusually good bowlers.—Toby Appel's Guide to the Orchestra

My greatest teacher was not a vocal coach, not the work of other singers, but the way Tommy Dorsey breathed and phrased on the trombone.—Frank Sinatra

Many a sinner has played himself into heaven on the trombone, thanks to the army.—George Bernard Shaw, Major Barbara

(Jack Teagarden) was certainly an astoundingly gifted trombonist who single-handedly created a whole new way of playing the trombone.—Gunther Schuller, The Swing Era.

J.J. Johnson found a way of adapting the instrument to bebop that was to influence every jazz trombonist that followed.—Steve Voce

Frank Rosolino was a towering genius and a trombone virtuoso of the jazz genre. His style was unique and instantly recognizable.—J.J. Johnson

Never look at the trombones. You'll only encourage them.—Richard Strauss

Note: If this item looks familiar, it is because I mistakenly posted it on October 17. Today, October 21, is the correct date of Dizzy's birth, so the Rifftides staff is moving the piece to where it belongs and adding a couple of links—DR.

This is the birthday of Dizzy Gillespie (1917-1993). In observance, here is a remarkable confluence of the talents of Gillespie and the master composer and arranger Robert Farnon (1917-2005). The piece is Gillespie's "Con Alma," orchestrated by Farnon and conducted by him at London's Royal Festival Hall in 1985. The delay between video and audio is mildly disconcerting, but the music is glorious.

For insight into how Dizzy's thoughtfulness and generosity affected one of many musicians, see today's entry in Diane Moser's blog.

For a personal remembrance, see this Rifftides archive piece.

Trumpeter, flugelhornist and composer Kenny Wheeler, now in his 80s, is a man of so few words that he is nearly silent, but John Fordham of The Guardian managed to persuade Wheeler to talk about himself for an article. Anyone interested in the unceasingly searching trumpeter, flugelhornist and composer will want to read Fordham's piece. Here's an excerpt:

He doesn't even call himself a composer, but someone who "takes pretty songs and joins them up." The soft-spoken Toronto-born musician has been sketching his enigmatic scenes for over half a century now, in which period - to his surprise - they've been massaged or creatively subverted by A-list jazz artists from the late Sir John Dankworth to sax stars Jan Garbarek and Evan Parker. Despite his 80 years, he retains his uniquely pure and melodically startling flugelhorn sound, and still composes profusely.

To read the whole thing, go here.

This video features Wheeler soloing with the George Gruntz big band on tour in Japan in the late 1980s. The tune is one of Wheeler's best known, "Everybody's Song But My Own." Gruntz is the pianist, Chris Hunter the alto saxophonist. Mike Richmond is on bass, Paul Motian on drums. I recognize Tom Varner on French horn, but don't have the names of the other musicians. This is a generous helping of Wheeler's playing.

For an evaluation from the Rifftides archives of one of Wheeler's albums and another honoring him, go here.

Rifftides reader Mike Paulson writes:

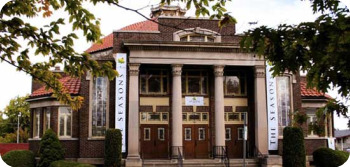

Looked up this clip on YouTube after watching Scott Robinson play "Isfahan" with Martin Wind at The Seasons the other evening.

I am amazed at how timeless this arrangement is. Hard to improve on perfection. Not sure why Duke had to hold the sheet music for Johnny Hodges.

Ellington and Billy Strayhorn got the inspiration for "Isfahan" during the band's tour of the Middle East in 1963. It became a part of The Far East Suite, which Ellington did not record until 1966. An educated guess is that in the 1964 performance—not 1965, as YouTube labels it—captured on the clip, Ellington or Strayhorn had recently written it and Hodges was giving the tune one of is first hearings, if not the first. If that is the case, his needing the lead sheet for reference is not surprising. It was not unusual for Ellington to have the band perform new music when the ink was barely dry.

The Scott Robinson performance of "Isfahan" that Mr. Paulson mentioned is covered in the Rifftides October 18 review two exhibits down.

Alto saxophonist Marion Brown, who came to prominence in the 1960s and '70s, died yesterday at age 79. He had been in an assisted living home in Hollywood, Florida, since  2005. Although some references list his birth year as 1935, he was born on September 8, 1931, in Atlanta, Georgia. Brown's career got a boost when John Coltrane chose him to be on Ascension. That 1965 album, in effect, was Coltrane's announcement that he was fully embracing free jazz. Brown also collaborated with Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp, Paul Bley and other figures in the free movement. In albums like his Afternoon of a Georgia Faun, he struck a balance between lyrical playing and the unbounded improvisation of the avant garde. This 1967 clip from Italy, with its murky picture, is a rare piece of video featuring Brown. The other members of his quartet are not identified. Be patient; the man who posted the clip has a promotional announcement.

2005. Although some references list his birth year as 1935, he was born on September 8, 1931, in Atlanta, Georgia. Brown's career got a boost when John Coltrane chose him to be on Ascension. That 1965 album, in effect, was Coltrane's announcement that he was fully embracing free jazz. Brown also collaborated with Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp, Paul Bley and other figures in the free movement. In albums like his Afternoon of a Georgia Faun, he struck a balance between lyrical playing and the unbounded improvisation of the avant garde. This 1967 clip from Italy, with its murky picture, is a rare piece of video featuring Brown. The other members of his quartet are not identified. Be patient; the man who posted the clip has a promotional announcement.

Hours before Friday night's concert at The Seasons Fall Festival, bassist Martin Wind's trio lost a third of its roster when drummer Matt Wilson returned home to attend to a family medical situation. Wind called Greg Williamson, who drove 150 miles from Seattle to Yakima across the Cascade Mountains in time for a quick talk-through before he joined Wind and saxophonist Scott Robinson on stage. The combination clicked in the trio's first half and after intermission when singer-pianist Dee Daniels joined them.

Had the audience not known of the last-minute substitution, nothing in the performance would have told them that Williamson had never before played with Wind and Robinson. Relying on experience, intuition and occasional clues from eye contact with Wind, Williamson, an imposing figure, cooked along as if the three had been together on the road for weeks—or, at least, had rehearsed. From the opener, Lucky Thompson's blues "The Plain But Simple Truth," they drew upon the common language of jazz and their finely tuned antennae. The program included three tunes from Wind's new CD, Get It! (See Doug's Picks in the center column of this page). He began his composition "Rainy River" soloing unaccompanied on the melody of that moody song and led into Robinson, who improvised a variation with suggestions of sadness akin to that of a folk ballad with gospel tinges. The bassist introduced "Gone With the Wind" as "my theme song." They jammed on it, Williamson locking with the bassist and the tenor man into blowing that went beyond bebop into freer territory.

Williamson, an imposing figure, cooked along as if the three had been together on the road for weeks—or, at least, had rehearsed. From the opener, Lucky Thompson's blues "The Plain But Simple Truth," they drew upon the common language of jazz and their finely tuned antennae. The program included three tunes from Wind's new CD, Get It! (See Doug's Picks in the center column of this page). He began his composition "Rainy River" soloing unaccompanied on the melody of that moody song and led into Robinson, who improvised a variation with suggestions of sadness akin to that of a folk ballad with gospel tinges. The bassist introduced "Gone With the Wind" as "my theme song." They jammed on it, Williamson locking with the bassist and the tenor man into blowing that went beyond bebop into freer territory.

Robinson did not bring along the arsenal of instruments that has made him a perennial winner in jazz polls' miscellaneous-instrument categories. There was nary a contrabass sax, sarusaphone or theremin in sight. He played only tenor saxophone and made clear why he attracts so much attention for his work on the instrument. He and Wind demonstrated their empathy in "Remember October 13th" From Wind's 2008 Salt 'N Pepper album. The piece went from delicacy in the bass-saxophone exposition of the melody into wild interaction among the three players. Robinson astonished the audience with the range of his playing, from nearly subsonic to beyond altissimo, and control of volume from all but subliminal to thunderous. In the context of his improvisation, his fusillades of honks and slap-tonguing were not vaudeville gags but made sense in the development of his lines.

Robinson did not bring along the arsenal of instruments that has made him a perennial winner in jazz polls' miscellaneous-instrument categories. There was nary a contrabass sax, sarusaphone or theremin in sight. He played only tenor saxophone and made clear why he attracts so much attention for his work on the instrument. He and Wind demonstrated their empathy in "Remember October 13th" From Wind's 2008 Salt 'N Pepper album. The piece went from delicacy in the bass-saxophone exposition of the melody into wild interaction among the three players. Robinson astonished the audience with the range of his playing, from nearly subsonic to beyond altissimo, and control of volume from all but subliminal to thunderous. In the context of his improvisation, his fusillades of honks and slap-tonguing were not vaudeville gags but made sense in the development of his lines.

Wind dedicated "We'll Be Together Again" to the late Hank Jones and opened it with a solo that radiated deep feeling. The trio segued into Billy Strayhorn's "Isfahan," Robinson giving pure melody with subtle references to Johnny Hodges. Wind delivered another memorable solo. Thad Jones' "Three and One" is a favorite of both Wind and Robinson. Wind plays it with the Vanguard Orchestra and recorded it on Get It. Robinson used it as a vehicle for bass saxophone in his album of Jones compositions. Following Wind's bowed solo, Robinson, blowing as he went, crossed the stage to the drum set and leaned with his tenor to within a foot or so of Williamson. They generated some of the hardest swing of the evening, Wind grinning at the power of it.

Following intermission, Daniels joined the trio. The power of her voice and a style marinated in blues captivated the crowd from the first notes of "Sweet Georgia Brown." After "Honeysuckle Rose," she moved to the Steinway to accompany herself in "A Song For You," the first of two Leon Russell songs in her set. The Wind Trio returned for "What a Difference a Day Made" and "This Masquerade," which contained a Robinson solo that uncovered possibilities Russell might not imagine were in his harmonies. Still at the piano, Daniels worked her way from blues shadings into unadulterated blues, belting Jimmy Reed's "Baby, What You Want From Me." She dug into the keyboard and set up Wind, Robinson and Williamson for powerful solos. Wind's arco choruses included pauses that he emphasized with the bassist's equivalent of Robinson's slap-tonguing, exquisitely timed whacks with the bow across the strings. The performance brought the audience to its feet demanding an encore. Daniels responded with "Who Can I Turn To" and wrapped up a concert that put an exclamation point on the jazz portion of the eight-day festival.

After "Honeysuckle Rose," she moved to the Steinway to accompany herself in "A Song For You," the first of two Leon Russell songs in her set. The Wind Trio returned for "What a Difference a Day Made" and "This Masquerade," which contained a Robinson solo that uncovered possibilities Russell might not imagine were in his harmonies. Still at the piano, Daniels worked her way from blues shadings into unadulterated blues, belting Jimmy Reed's "Baby, What You Want From Me." She dug into the keyboard and set up Wind, Robinson and Williamson for powerful solos. Wind's arco choruses included pauses that he emphasized with the bassist's equivalent of Robinson's slap-tonguing, exquisitely timed whacks with the bow across the strings. The performance brought the audience to its feet demanding an encore. Daniels responded with "Who Can I Turn To" and wrapped up a concert that put an exclamation point on the jazz portion of the eight-day festival.

There is no video of The Seasons festival performance of the Wind trio, but there is of Wind, Robinson, Matt Wilson and pianist Bill Mays at the Jazz Baltica Festival in Germany in 2008. Here, they play Paul Chambers' "Tale of the Fingers." Following Wilson's introduction, Robinson begins on bass clarinet and later solos on cornet and tenor saxophone.

Mark Murphy may have had his problems the past few years, but rumors that he is not singing well appear to be unfounded. Rifftides reader and occasional correspondent Jim Brown sent a report with evidence.

A year or two ago, there were suggestions that Mark was in bad health, perhaps had dementia, and that he might not be performing again. Here's a performance from last summer that will blow you away. Whatever his health problems might have been, it seems clear that he's still hanging in. There are several other pieces of video from the same set that are worth watching, but this one is the masterpiece. Pianist Jon Cowherd, bassist Boris Kozlov and drummer Willard Dyson are the accompanists in this medley from the Kitano in New York.

Following four days of downtime forced by computer and internet problems, Rifftides offers a brief summary of the first five days of The Seasons eight-day Fall Festival.

In the first of two appearances, the Tom Harrell Quintet opened the festival Friday evening in The Seasons' acoustically perfect performance hall in Yakima, Washington. With the polish and assurance developed in their years together, Harrell's band combined an edge of adventurousness that, by the time the first piece ended, had the audience buzzing. Alternating between flugelhorn and trumpet, Harrell locked up with  tenor saxophonist Wayne Escoffery in the lines of the leader's closely crafted compositions. Harrell, Escoffery and pianist Danny Grissett soloed brilliantly and at length. Some of the pieces were from Harrell's new CD Roman Nights. The rich harmonies and compelling melody of "Let the Children Play" captivated the audience. Escoffery, bassist Ugonna Okegwo and drummer Rudy Royston left the stage to Harrell and Grissett for an achingly beautiful duet performance of "Roman Nights." The song seems bound to take its place with "Sail Away" as one of Harrell's finest writing achievements.

tenor saxophonist Wayne Escoffery in the lines of the leader's closely crafted compositions. Harrell, Escoffery and pianist Danny Grissett soloed brilliantly and at length. Some of the pieces were from Harrell's new CD Roman Nights. The rich harmonies and compelling melody of "Let the Children Play" captivated the audience. Escoffery, bassist Ugonna Okegwo and drummer Rudy Royston left the stage to Harrell and Grissett for an achingly beautiful duet performance of "Roman Nights." The song seems bound to take its place with "Sail Away" as one of Harrell's finest writing achievements.

For The Seasons festival, Harrell premiered "Thought Waves" and "Modern Times." The latter title may be laced with mild irony. Its rhythmic emphasis and melodic simplicity are in the mold of tunes written by Horace Silver, in whose quintet Harrell played for four years in the 1970s. The improvisation by the quintet, however, was strictly of the new century, with expansive soloing by all hands. At the end of the concert, the crowd was on its feet cheering and brought Harrell out for three curtain calls.

Saturday night, the Harrells and pianist Bill Mays played a concert of new and old music for orchestra and soloists. It opened with the Yakima Symphony Chamber orchestra, conducted by its music director Lawrence Golan, playing Gunther Schuller's piquant arrangements of "The Entertainer" and "The Early Winners," early 20th century rags by Scott Joplin, Harrell and his quintet joined the orchestra for four sections of Harrell's "Wise Children." He recorded the suite in 2003 but this music from it received its first live performance at The Seasons. "Wise Children" draws on inspiration from African, Brazilian, Afro-Cuban and European music. It represents some of Harrell's most resourceful writing—the mesmerizing vamp played by strings and percussion under his horn on "Kalimba," the gorgeous melody of "Ballad in D" intoned by Escoffery, the harmonies of the elegiac title piece and the Latin rhythm fiesta called "Paz."

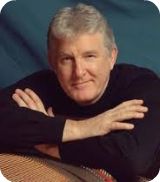

Following intermission in this ambitious program, Golan and the chamber orchestra played three pieces inspired by jazz in its early years. First was Darius Milhaud's La création du monde, written in 1923. Full of dissonances, blues references and—fittingly—great creative energy, the Milhaud is often described as ahead of its time in its use of jazz in a classical setting. Then, five years almost to the day after his trio gave the performance that opened The Seasons, Bill Mays went to the Steinway as soloist with the orchestra. First, they played George Antheil's 1925 A Jazz Symphony, a 12-minute romp whose raucousness, intensity, dense orchestration and humor at once admire the jazz of the twenties and poke fun at it. Integrated into the piece, the piano part places on the performer huge technical demands. Mays met them with gusto.

his trio gave the performance that opened The Seasons, Bill Mays went to the Steinway as soloist with the orchestra. First, they played George Antheil's 1925 A Jazz Symphony, a 12-minute romp whose raucousness, intensity, dense orchestration and humor at once admire the jazz of the twenties and poke fun at it. Integrated into the piece, the piano part places on the performer huge technical demands. Mays met them with gusto.

The concert concluded with George Gershwin's Rhapsody In Blue in the version Paul Whiteman commissioned for his Experiment in Modern Music concert at Aeolian Hall in New York. Gershwin was the piano soloist. Mays is the first Rhapsody In Blue pianist to open up the piece for improvisation since the composer that night in 1924. From the famous opening clarinet glissando, memorably executed by Jeffrey Brooks, the orchestra and Mays were fully into the spirit of the piece. But near the end, when Golan rested his baton, Mays took ownership. His more than five minutes of improvisation built on Gershwin's themes but also had perspective on jazz development over eight decades and incorporated idioms from all of it. The intensity and passion of his spontaneous invention brought a roar from the audience as the orchestra reentered and, when the piece ended, there was sustained applause that resulted in Mays' repeated returns to the stage for bows. When the entire Saturday night concert was repeated for a new audience on Sunday afternoon, the orchestra lacked the same edge in the Gershwin, but Mays' improvisation was even more powerful, with harder swing and new elements of whimsy, including several bebop quotes. If this Rhapsody In Blue wasn't recorded, it should have been.

Sunday evening, recovered from his exertions of the afternoon, Mays returned for a concert reuniting him with bassist Martin Wind and drummer Matt Wilson. They had not played together as the Bill Mays Trio since a concert at The Seasons in 2007. No refamiliarization was necessary. From "With a Song in My Heart" to "You Go to My Head" at the end, they had the energy and empathy that established them as perennial favorites in polls. A few high points in a concert that was a high point:

Sunday evening, recovered from his exertions of the afternoon, Mays returned for a concert reuniting him with bassist Martin Wind and drummer Matt Wilson. They had not played together as the Bill Mays Trio since a concert at The Seasons in 2007. No refamiliarization was necessary. From "With a Song in My Heart" to "You Go to My Head" at the end, they had the energy and empathy that established them as perennial favorites in polls. A few high points in a concert that was a high point:

Ravel

Ravel

Wilson's "Music House" solo, complete with a press roll that he made so quiet it could barely be heard, and use of his left foot as a snare drum damper

In the same piece, the blues feeling the trio developed, reminiscent of a 1940s jump band

Thelonious Monk's rarely played "Eronel, with all kinds of Monkish business by Mays, and Wind beginning his long, adventurous solo with a chorus of melody

Because of the computer kerfuffle, I missed most of the first half of Monday's concert by The Finisterra Piano Trio and The Seasons String Quartet, launching the extensive classical portions of the festival. It had music by Gershwin, Samuel Barber, David Rakowski , Wang Jie, Beth Wiemann, Michael Laster and Slavko Krstic. Laster and  Krstic are among nine composition fellows studying at the festival with artistic director Daron Hagen. I heard the last song in Rakowski's Double Fantasy, played by Finisterra and sung with passion in Spanish by soprano Gilda Lyons. Following intermission, Finisterra played Beethoven's Piano Trio in D Major, Op. 70, the roar and rumble of its powerful middle movement anchored by pianist Tanya Stambuk, with violinist Simon James and cellist Kevin Krentz.

Krstic are among nine composition fellows studying at the festival with artistic director Daron Hagen. I heard the last song in Rakowski's Double Fantasy, played by Finisterra and sung with passion in Spanish by soprano Gilda Lyons. Following intermission, Finisterra played Beethoven's Piano Trio in D Major, Op. 70, the roar and rumble of its powerful middle movement anchored by pianist Tanya Stambuk, with violinist Simon James and cellist Kevin Krentz.

There was more chamber music last night, including two pieces by composer-in-residence Larry Alan Smith. His song cycle on poetry of Emily Dickinson, A Slash of Blue! A Sweep of Gray!, got a stunning performance by Ms. Lyons and pianist Robert Frankenberry, as did the versatile Ms. Lyons' compositions "Owl Light" and "Between Wolf and Dog" by Krentz playing unaccompanied cello. Krentz played three of Hagen's Love Songs for Cello and Piano with the composer accompanying.

Tonight, the festival continues with Michael Wimberly's Africa: The Power of Drum and Dance. This is a return appearance at the festival by the New York percussion expert, who brings with him members of his troupe and incorporates into his concert students from schools throughout the Yakima valley for a carnival of drumming, dancing and singing. It is a vital part of the educational outreach function of The Seasons' nonprofit contribution to the culture of the region.

It wasn't sludge (see yesterday's entry), but it did get worse. The problem was intermittent and untraceable even with cable company equipment so sophisticated it might be on loan from the CIA. Now, however, after a pair of two-hour visits from techs, long, baffling phone calls with two other techs and, finally, the purchase and installation of a new piece of equipment, the Rifftides World Headquarters web connection seems alive and stable. That's what I thought 24 hours ago. After a glass of something red and a good night's sleep, I'll try to post a catchup piece on The Seasons Fall Festival. Hope springs eternal.

night's sleep, I'll try to post a catchup piece on The Seasons Fall Festival. Hope springs eternal.

It could have been worse—toxic red sludge, for instance.

The technician just left after performing CPR on the internet connection, which was out of commission for 48 hours. The Rifftides staff will resume posting soon. Now, ears open wide and notebook in hand, we're off to The Seasons for the next concerts of the Fall Festival. This afternoon,Tom Harrell's quintet and pianist Bill Mays are performing Harell, Antheil and Gershwin with the Yakima Symphony Chamber Orchestra. Tonight, it's the Mays trio with Martin Wind and Matt Wilson.

The technician just left after performing CPR on the internet connection, which was out of commission for 48 hours. The Rifftides staff will resume posting soon. Now, ears open wide and notebook in hand, we're off to The Seasons for the next concerts of the Fall Festival. This afternoon,Tom Harrell's quintet and pianist Bill Mays are performing Harell, Antheil and Gershwin with the Yakima Symphony Chamber Orchestra. Tonight, it's the Mays trio with Martin Wind and Matt Wilson.

In the meantime, if Thelonious Monk were alive he would be celebrating his 93rd birthday. Let us all celebrate Monk. This 1966 performance of "Blue Monk" with Charlie Rouse, Larry Gales and Ben Riley has been viewed 1,140,150 times. No wonder.

Continuing the not quite helter-skelter survey of recent recordings that we began last week, here are four more worth your attention:

Ted Rosenthal, Impromptu (Playscape). Rosenthal interprets classical composers' themes with respect, but he is not reluctant to add or subtract an element to make them work for improvisation. The  pianist, bassist Noriko Ueda and drummer Quncy Davis approach pieces by Bach, Schubert and Brahms as they would those by other revered composers—say, Monk, Ellington and Mulligan. Rosenthal found that only the main strain of Chopin's Nocturne in F minor suited the trio's purpose, so that's what they blow on. It becomes a gorgeous standard ballad from the Great Polish Songbook. Tchaikovsky's "June," the Barcarolle in G minor from The Seasons, has undertones of blues and parallel-hands passages reminiscent of Erroll Garner or Lennie Tristano. Rosenthal gives the Brahms Intermezzo in B Flat minor an overt blues treatment, with a lunging samba feel in the rhythm. The Schubert Impromptu in G flat goes from 6/8 to 4/4 and culminates in a stunning role reversal of the hands as Rosenthal plays the melody in the bass clef and decorates it with lightning runs on top. The trio also get their licks in with Mozart, Puccini, Bach and Schumann. This is not the tiresome foolery that used to be called "jazzing the classics." It is serious music making on substantial material, and it is great fun.

pianist, bassist Noriko Ueda and drummer Quncy Davis approach pieces by Bach, Schubert and Brahms as they would those by other revered composers—say, Monk, Ellington and Mulligan. Rosenthal found that only the main strain of Chopin's Nocturne in F minor suited the trio's purpose, so that's what they blow on. It becomes a gorgeous standard ballad from the Great Polish Songbook. Tchaikovsky's "June," the Barcarolle in G minor from The Seasons, has undertones of blues and parallel-hands passages reminiscent of Erroll Garner or Lennie Tristano. Rosenthal gives the Brahms Intermezzo in B Flat minor an overt blues treatment, with a lunging samba feel in the rhythm. The Schubert Impromptu in G flat goes from 6/8 to 4/4 and culminates in a stunning role reversal of the hands as Rosenthal plays the melody in the bass clef and decorates it with lightning runs on top. The trio also get their licks in with Mozart, Puccini, Bach and Schumann. This is not the tiresome foolery that used to be called "jazzing the classics." It is serious music making on substantial material, and it is great fun.

Regina Carter, Reverse Thread (E1). There are moments on violinist Carter's most recent CD that evoke Cajun music, Brazilian choro, Cuban danzon, even the feeling of an Appalachian hoedown. Carter's inspiration for this collection, hoedown perhaps aside, is from the African sources of much music we often assume to be from South America or the Caribbean. She spent three years and part of her half-million-dollar MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant researching African music, traveling to the continent to immerse herself in it. The result is a dozen pieces with enormous variety. Most are interpretations of traditional music, or songs by composers from Kenya, Senegal, Mali and South Africa. Carter's composition "Day Dreaming on the Niger" blends into the flow of the African pieces. Yacouba Sissoko, a virtuoso of the 21-stringed Malian kora, is effective on five tracks, but the African atmospherics and the authenticity don't depend on him. Carter, bassist Chris Lightcap, guitarist Adam Rogers, accordionists Gary Versace and Will Holshouser, and drummer Alvester Garnett have absorbed the ethos and rhythms of the music. Through it all is the incomparably rich violin and imagination of Regina Carter.

African sources of much music we often assume to be from South America or the Caribbean. She spent three years and part of her half-million-dollar MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant researching African music, traveling to the continent to immerse herself in it. The result is a dozen pieces with enormous variety. Most are interpretations of traditional music, or songs by composers from Kenya, Senegal, Mali and South Africa. Carter's composition "Day Dreaming on the Niger" blends into the flow of the African pieces. Yacouba Sissoko, a virtuoso of the 21-stringed Malian kora, is effective on five tracks, but the African atmospherics and the authenticity don't depend on him. Carter, bassist Chris Lightcap, guitarist Adam Rogers, accordionists Gary Versace and Will Holshouser, and drummer Alvester Garnett have absorbed the ethos and rhythms of the music. Through it all is the incomparably rich violin and imagination of Regina Carter.

Billy Bang, Prayer For Peace (TUM). In an album mostly of his own compositions, the violinist opens with Stuff Smith's "Only Time Will Tell." Bang and trumpeter James Zollar might be  summoning the spirits of the seminal jazz violinist Smith (1909-1967) and his Onyx Club sidekick of the 1930s, Jonah Jones. The rest of the CD is redolent of the music Bang has made with Sun Ra, Don Cherry, the bassist Sirone and others in the avant garde, and of his love for John Coltrane. That is not to say that it is experimental or inaccessible. Even at its most daring, Bang's music has always had an engaging old-timey quality that he transmits to those who play with him, including Zollar, bassist Todd Nicholson, pianist Andrew Bemkey and drummer Newman Taylor-Baker, the band of young musicians he has employed for some years. The title tune, just short of 20 minutes, runs in a tranquil modal course that reflects the quest for peace that Bang has promoted with music since his experience in the Viet Nam war. Bang's danceable version of "Chan Chan," the Afro-Cuban anthem made famous by the Buena Vista Social Club, is among the pleasures here. The Finnish record company TUM lavished commendable care on the sonic production and packaging of this CD.

summoning the spirits of the seminal jazz violinist Smith (1909-1967) and his Onyx Club sidekick of the 1930s, Jonah Jones. The rest of the CD is redolent of the music Bang has made with Sun Ra, Don Cherry, the bassist Sirone and others in the avant garde, and of his love for John Coltrane. That is not to say that it is experimental or inaccessible. Even at its most daring, Bang's music has always had an engaging old-timey quality that he transmits to those who play with him, including Zollar, bassist Todd Nicholson, pianist Andrew Bemkey and drummer Newman Taylor-Baker, the band of young musicians he has employed for some years. The title tune, just short of 20 minutes, runs in a tranquil modal course that reflects the quest for peace that Bang has promoted with music since his experience in the Viet Nam war. Bang's danceable version of "Chan Chan," the Afro-Cuban anthem made famous by the Buena Vista Social Club, is among the pleasures here. The Finnish record company TUM lavished commendable care on the sonic production and packaging of this CD.

Jeff Chang, It's Not What You Think (Chee May). Chang came to the United States from Taiwan in his teens. He studied at the New England Conservatory with George Russell, George Garzone and Steve Lacy, among others, and emerged a fresh voice on alto saxophone. His debut CD is impressive for his big sound, his broad conceptual range, the quartet's cohesiveness and the quality of his original compositions. In any given piece, Chang is likely to go from lyrical melody to mutual quartet improvisation full of risk and exhilaration. Fellow NEC grads pianist Carmen Staaf, bassist Kendall Eddy and drummer Austin McMahon are his empathetic rhythm section. Staaf's touch, subtle way with chords and firm time interact intriguingly with Chang's post-bop inventiveness.

He studied at the New England Conservatory with George Russell, George Garzone and Steve Lacy, among others, and emerged a fresh voice on alto saxophone. His debut CD is impressive for his big sound, his broad conceptual range, the quartet's cohesiveness and the quality of his original compositions. In any given piece, Chang is likely to go from lyrical melody to mutual quartet improvisation full of risk and exhilaration. Fellow NEC grads pianist Carmen Staaf, bassist Kendall Eddy and drummer Austin McMahon are his empathetic rhythm section. Staaf's touch, subtle way with chords and firm time interact intriguingly with Chang's post-bop inventiveness.

Among the dozens of musicians either already here or headed toward my current home town for the eight days of The Seasons Fall Festival are Tom Harrell and his quintet, Bill Mays, Martin Wind, Matt Wilson, Scott Robinson, the African percussion expert Michael Wimberly, composer Daron Hagen and a raft of classical players, composers and conductors. Thursday evening I heard Harrell rehearsing his Wise Children suite with the Yakima Symphony Chamber Orchestra. Whew. It's something to look forward to. For the schedule and details of the festival, go here.

Robinson will appear with Wilson and singer-pianist Dee Daniels in Wind's group. Coincidentaly, Bill Kirchner is devoting his radio program this weekend to Robinson and his menagerie of every instrument known to man. That's only a slight exaggeration. Here's Kirchner's listening advisory:

Recently, I taped my next one-hour show for the "Jazz From The Archives" series. Presented by the Institute of Jazz Studies, the series runs every Sunday on WBGO-FM (88.3) in the New York-New Jersey area.

Jazz has had some remarkable multi-instrumentalists, but probably none with

the scope of Scott Robinson (b. 1959). A short list of his instruments includes saxophones (from sopranino to contrabass), flutes, clarinets, trumpet, trombone and theremin--all played on a world-class level. And he is comfortable in jazz idioms ranging from the 1920s to the avant-garde.We'll hear Robinson playing with the Bob Brookmeyer, Tom Pierson, and Maria Schneider orchestras, as well as with drummer Klaus Suonsaari and his own small groups.

The show will air this Sunday, October 10, from 11 p.m. to midnight, Eastern Daylight Time.

NOTE: If you live outside the New York City metropolitan area, WBGO also

broadcasts on the Internet at www.wbgo.org.

If you are attending The Seasons Fall Festival, I'll be around. Please say hello. I may even take notes and post a report or two on Rifftides.

While the Rifftides staff prepares the next installment of In Breve, we don't want you to feel abandoned. We have been holding the following video for just such an occasion—Benny Green, piano; Ray Brown,bass; Jeff Hamilton, drums; and the WDR Big Band conducted by John Clayton, in 1994, playing Duke Ellington's "Cotton Tail." In the right hands, "I Got Rhythm's" harmonic changes never grow old. Green has moments in which he might be the reincarnation of Bud Powell. The saxophone section brings back Ben Webster.

Miles Davis, Bitches Brew 40th Anniversary (Columbia). Here is everything you are likely to want to hear, know, ask or think about Davis' full-fledged leap into the rock ethic that informed his music in the 1970s. It is a lavish boxed package of two LPs, three CDs, a DVD, a book and a packet of posters, ticket replicas, photos, proof sheets and Columbia memos. For those willing to spend more than a hundred bucks, the memorabilia aspect is an attraction, but the music is the thing. Sidemen including Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea, John McLaughlin, Dave Holland, and post-production maven Teo Macero, helped Miles deliver on his celebrated claim, "I could put together the greatest rock & roll band you ever heard." Rock never lived up to his example.

Irene Kral, Second Chance (Jazzed Media). Kral's stock in trade was perfection—of intonation, time, feeling, diction and lyric interpretation. She sang with little movement, no show biz mannerisms, nothing resembling schtick. She was so good at 25 that in 1957 Maynard Ferguson hired her on the spot after hearing one song. Alan Broadbent became Kral's piano accompanist in 1974. Until her death four years later, they performed together on a plane of empathy rarely achieved in any genre of music. This previously unissued club performance from 1975 is an essential addition to their small discography.

Martin Wind, Get It? (Laika). The quartet's feeling of controlled abandon, symbolized in the cover shot, is notable in the title tune inspired by James Brown. There's a sense of slight danger even in the stately treatment of Billy Strayhorn's "Isfahan" and Wind's atmospheric, blues-inflected "Rainy River." The chance-taking is at a high point in Thad Jones' "Three and One," with a Scott Robinson tenor sax solo that slithers, growls and wails. Wind, Robinson, pianist Bill Cunliffe and drummer Tim Horner are a compelling combination. On two pieces, Wind makes his debut on cello.

Johnny Mercer, This Time The Dream's On Me (Warner Bros). Producer-director Bruce Ricker does a masterly job of integrating new and old material into a thorough biography of the great lyricist. The story of Mercer's life and artistry melds film clips and recordings of Bing Crosby, Fred Astaire, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong and Mercer singing his songs. Colleagues including Johnny Mandel and Tony Bennett offer assessments of his gifts, and Mercer himself reflects on his career. There is no attempt to gloss over his drinking and affairs, but they are in proper perspective. The film leaves the viewer with an amazed sense of Mercer's brilliance, consistency and adaptability.

Nat Hentoff, At The Jazz Band Ball: Sixty Years On The Jazz Scene (U of California Press). Hentoff is our leading avatar of the proposition that jazz is a living expression of the principles embedded in the US constitution, of which he is also a scholar. He does not deal in technical analysis of music. He gives strong, informed opinions and tells stories about those he knew or knows intimately, among them Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, John Coltrane and Clark Terry. But he also writes about less famous figures whose blazing individuality "puts their lives, memories and expectations into the penetrating immediacy of their music." Hentoff wears his love for jazz on his sleeve, and he balances it with insight, knowledge and long experience.

Rifftides reader Garret Gannuch practices pediatric radiology in Denver. When he moved to Colorado, his Louisiana soul went with him. A week ago, Dr. Gannuch traveled into the country south of Denver to hear a fellow New Orleanian. He knew that, like nearly anyone who's ever lived there, I'll never get over my love affair with New Orleans and he wrote me about the experience. I asked him if I could let you in on it. He said yes. Here is his report.

I attended a solo piano concert by Henry Butler at the Cherokee Ranch andCastle in Douglas Country, Colorado. The setting couldn't be better. The music is presented on a ranch amid more than 3,000 preserved acres south of Denver in a beautiful, relaxed great hall comfortably seating 50 or so music lovers. The food is good too.

Butler, the jazz and blues pianist, composer, and singer from New Orleans, gave an energetic and uplifting performance. Influenced by Sir Roland Hanna, James Booker and Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd), his music is infused with the rhythms of New Orleans piano— a style rarely mentioned in blogs and articles—and the blues. His speech and manner are gentle and humorous. His playing is forceful.

He opened the historically informed program with "Trocha," a tango from 1896 by William Henderson Tyres. Essentially playing the piece straight, he let the Cuban dance rhythms dominate the hall. You could hear and feel the relationships between Caribbean, New Orleans, jazz and blues music. Butler permeated the evening with the kind of rhythms New Orleans second-liners dance to as he built on the mood set by the opening number. He followed with tour de force versions of "Wolverine Blues" by Jelly Roll Morton

(1906), "Buddy Bolden's Blues" ("Funky Butt") by Willy Cornish (1902) and Morton's "King Porter Stomp" (1923). But even when he moved on to "How to Handle a Woman" by Lerner and Loewe, "Fiddler on the Roof" by Bock and Harnick, "If I Only Had a Heart" and "Ding-Dong! The Witch is Dead" by Arlen and Harburg, the heavily syncopated and dotted-rhythm style of New Orleans piano dominated. Everything was infused with the blues.

In the second half of the program he introduced powerful vocals into the evening and played his own "New Orleanian in Exile," "Booker Time," and "I Got My Eyes on You" as well as "Sitting on the Dock of the Bay" by Cropper and Redding. For encores he sang a soulful version of Kern and Hammerstein's "Ol' Man River," the best I have ever heard live, and got the room dancing to Professor Longhair's "Go to the Mardi Gras."

Reviewers often mention Butler's "thunderous" approach to the keyboard, use of syncopated block chords and clusters, fast interacting arpeggiated lines, the interaction between hands and the strong rhythms. But, for me, there is more than a heavy touch. I can hear his love for classical music. You can tell he listened to Alicia de Larrocha, Andre Watts, Andre Previn, Walter Gieseking, Horowitz, as well as jazz greats Peterson, Tatum, Jarett and Corea—and loves them all. He produces an original, rich, deep gumbo that brings me back to New Orleans, inviting me to move with the music and participate in the event.

Butler gives yearly trio and solo performances at Cherokee Ranch. Check out their varied schedule.

Thanks to Dr. Gannuch for sharing his impressions. As far as I know, there is no video of Butler's Cherokee Ranch concert. Here he is during his stint last year as artist in residence at Mendocino College in northern California. Listen to him turn a lemon into lemonade at about 2:45.

Butler's CD called Pianola is a collection of his astonishing solo performances.

During my early development as a listener, I was immersed in the works of Charlie Parker, Bud Powell and Miles Davis when along came Johnny Wittwer. Wittwer was a Seattle pianist who had been been important in the traditional jazz revival on the west coast in the 1940s. Early in that decade he had a trio with clarinetist Joe Darensbourg and drummer Keith Purvis. Later, he was active in San Francisco and worked with Kid Ory and Wingy Manone, among others. In the dialectic of the absurd but deadly serious 1950s division between boppers and moldy figs, most boppers regarded him as hopelessly moldy. Too bad for them. Wittwer was a superb pianist who knew everything there was to know about Jelly Roll Morton. He could explain and demonstrate Jelly to a faretheewell. Although he chose not to play it, he also knew what modern jazz was made of. As an exercise in whimsy or irony, he would toss off a few bars of an uncannily accurate Horace Silver impression.

For a whippersnapper, hanging out with John was not only a fine education but also great fun. He was as hip to English literature as he was to Jelly Roll. Discussions with Wittwer helped me with my class on the Victorian novel. All of that came to mind when I stumbled across this Wittwer solo recording from 1945. It's good to hear him again.

Wittwer once suggested that he and I write a Broadway musical together. He would do the music, I the words. It would star Pat Suzuki, whom we both knew. I went in the Marine Corps and the collaboration never happened. Pat went on to star in The Flower Drum Song.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Kindly direct your attention to the display under the legend Doug's Picks in the center column. You will find new recommendations of CDs, a DVD and a book.

Kindly direct your attention to the display under the legend Doug's Picks in the center column. You will find new recommendations of CDs, a DVD and a book.