Rifftides: July 2010 Archives

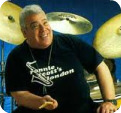

Martin Drew died in London on Thursday of a heart attack.  Drew was the house drummer at Ronnie Scott's club for 20 years beginning in 1975. He gained his greatest fame during the same period and into the new century playing around the world in Oscar Peterson's trios and quartets. Recently he led his quintet The New Couriers, formed in tribute to the late saxophonist Tubby Hayes, with whom he played in the '60s and early '70s.

Drew was the house drummer at Ronnie Scott's club for 20 years beginning in 1975. He gained his greatest fame during the same period and into the new century playing around the world in Oscar Peterson's trios and quartets. Recently he led his quintet The New Couriers, formed in tribute to the late saxophonist Tubby Hayes, with whom he played in the '60s and early '70s.

A master of his instrument who seemed uninterested in flaunting his considerable technique, Drew harnessed it in the service of swing and the dynamics of group interaction. Here he is with Peterson and bassist Niels Henning Ørsted Pedersen in Berlin in 1985. Despite the erroneous titles on the YouTube screen as the playing begins, the piece is "Cakewalk."

The French jazz critic Alain Gerber is also a novelist, or vice versa. He published a book in 2007 that may be a biography, a novel, or both. Its title in French is Paul Desmond et le côté féminin du monde, or Paul Desmond and the Feminine Side of the World. That is the extent of my ability to translate from French to English, and I owe it to Google. I'm the guy who gets by in France for two weeks at a time with Excusez-moi de vous deranger. Here is the Googleized English version of the French publisher's description of the book:

Side of the World. That is the extent of my ability to translate from French to English, and I owe it to Google. I'm the guy who gets by in France for two weeks at a time with Excusez-moi de vous deranger. Here is the Googleized English version of the French publisher's description of the book:

He loved burning cigarettes at both ends. He loved scotch dewars with a youthful zeal, and then go home to around the early morning, waking in the middle of the afternoon and groping her horn-rimmed spectacles, and contemplate his hangover in the mirror of the bathroom, with a sense of accomplishment. He liked to kill time with extreme gentleness. Dying without impatience. discuss the eye. Talking about literature, poetry, ballet, film, comedy. But, above all, he loved women. [...] They were his smoke without fire. telling and music prodigy, this dissipation of shimmer, this splendid infertility.

As Desmond's English language biographer and drinking companion, I now have one more reason to regret his no longer being among us. I would give about anything—let's say a bottle of Dewars—to read that passage to him, looking up and pausing after "groping her horn-rimmed spectacles." Paul infrequently laughed out loud. He was more given to knowing chuckles, but that line might have done the trick. The French website offers this passage from the book:

"All it was - a saxophonist, star or unloved, Don Juan, a man without a wife,a writer without literature, alcoholic, desperate, lonely, good guest, a nostalgic, casual, maker of epigrams and witticisms, amateur puns, storyteller, and many other things - all he was, he never was really "

To see it in Alain Gerber's native tongue, go here.

For the English translation of the web page, go here. I can find no evidence that Paul Desmond et le côté féminin du monde exists in anything but French.

Skill in languages is unnecessary for the enjoyment of Desmond, Jim Hall, Gene Wright and Connie Kay playing Matt Dennis's timeless ballad "Angel Eyes." This is from one of Paul's RCA quartet albums of the 1960s. Seldom mentioned in assessments of Desmond's and Hall's playing is their ability to find blues implications in non-blues pieces.

The Rifftides staff is pleased to announce a new batch of the recommendations known as Doug's Picks. Please proceed to the center column, scroll down and,

David Weiss & Point Of Departure, Snuck In (Sunnyside). Trumpeter Weiss's heart may be in the 1960s, but he and his young band operate very much in the present. His solo style is largely a bequest from the late Freddie Hubbard, with whom he worked closely as a player and arranger. His repertoire here consists of pieces by Herbie Hancock, Andrew Hill and Tony Williams, plus two from the neglected Detroit trumpeter Charles Moore. Weiss, tenor saxophonist J.D. Allan, guitarist Nir Felder, bassist Matt Clohesy and drummer Jamire Williams are expansive and full of vigor. With the shortest track running nine minutes, the soloists go long but maintain focus—theirs and the listener's.

David Weiss & Point Of Departure, Snuck In (Sunnyside). Trumpeter Weiss's heart may be in the 1960s, but he and his young band operate very much in the present. His solo style is largely a bequest from the late Freddie Hubbard, with whom he worked closely as a player and arranger. His repertoire here consists of pieces by Herbie Hancock, Andrew Hill and Tony Williams, plus two from the neglected Detroit trumpeter Charles Moore. Weiss, tenor saxophonist J.D. Allan, guitarist Nir Felder, bassist Matt Clohesy and drummer Jamire Williams are expansive and full of vigor. With the shortest track running nine minutes, the soloists go long but maintain focus—theirs and the listener's.

Esperanza Spalding, Chamber Music Society (Heads Up). The contrarian impulse is to briskly walk away from hype about the latest sensation du jour, but critical duty says, listen anyway. In Spalding's case, I'm glad I listened. She is an accomplished bassist with depth of tone, penetrating timbre and good note choices. Her singing has clarity and lightness. She is consistently in tune. Spalding writes and arranges well. With a small string ensemble, piano, drums and percussion, she interprets William Blake, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Dmitri Tiomkin and several pieces of her own. Her duet with Gretchen Parlato on Jobim's "Inútil Pasagem" is a triumph of intricate simplicity. One with Milton Nascimento in "Apple Blossoms" has a lovely blend of their voices but bogs down in an awkward narrative lyric, one flaw in a captivating CD.

Esperanza Spalding, Chamber Music Society (Heads Up). The contrarian impulse is to briskly walk away from hype about the latest sensation du jour, but critical duty says, listen anyway. In Spalding's case, I'm glad I listened. She is an accomplished bassist with depth of tone, penetrating timbre and good note choices. Her singing has clarity and lightness. She is consistently in tune. Spalding writes and arranges well. With a small string ensemble, piano, drums and percussion, she interprets William Blake, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Dmitri Tiomkin and several pieces of her own. Her duet with Gretchen Parlato on Jobim's "Inútil Pasagem" is a triumph of intricate simplicity. One with Milton Nascimento in "Apple Blossoms" has a lovely blend of their voices but bogs down in an awkward narrative lyric, one flaw in a captivating CD.

Joe Sardaro, Lost In The Stars (Catch My Drift). Last year, I mentioned in a review of Joe Sardaro's Protégé that the singer's 1986 vinyl album Lost In The Stars had never been reissued. Now, happily, it is on CD. Sardaro recruited high-level backing for his first recording; drummer Shelly Manne, bassist Monte Budwig, guitarist Al Viola, saxophonist/flutist Sam Most and pianist John Knapp. To quote my 1987 Jazz Times review of the LP, "A light baritone without spectacular range or notable resonance, he depends on taste, swing, diction and lyric interpretation. Those elements serve him well..." Most's tenor sax solos are delightful. The CD adds five songs recently recorded by Sardaro. He sings them pleasantly but with less steady intonation than in the original eleven.

Joe Sardaro, Lost In The Stars (Catch My Drift). Last year, I mentioned in a review of Joe Sardaro's Protégé that the singer's 1986 vinyl album Lost In The Stars had never been reissued. Now, happily, it is on CD. Sardaro recruited high-level backing for his first recording; drummer Shelly Manne, bassist Monte Budwig, guitarist Al Viola, saxophonist/flutist Sam Most and pianist John Knapp. To quote my 1987 Jazz Times review of the LP, "A light baritone without spectacular range or notable resonance, he depends on taste, swing, diction and lyric interpretation. Those elements serve him well..." Most's tenor sax solos are delightful. The CD adds five songs recently recorded by Sardaro. He sings them pleasantly but with less steady intonation than in the original eleven.

Jimmy And Percy Heath, Jazz Master Class (Artists House). In 2004, the year before bassist Percy Heath died, he and his saxophonist/composer brother Jimmy appeared in John Snyder's master class series at New York University. A pair of DVDs captures them in several stunning duets, critiquing student performances of Jimmy's tunes and being interviewed by author Gary Giddins. We also see pre- and post-master class conversations with the students, transcriptions of solos rolling across the screen as the solos are played and Giddins talking at length about the Heath Brothers' importance. Percy's and Jimmy's charm, humor, erudition and contrasting personalities come across strongly. This set is a highlight in an invaluable Artists House project.

Jimmy And Percy Heath, Jazz Master Class (Artists House). In 2004, the year before bassist Percy Heath died, he and his saxophonist/composer brother Jimmy appeared in John Snyder's master class series at New York University. A pair of DVDs captures them in several stunning duets, critiquing student performances of Jimmy's tunes and being interviewed by author Gary Giddins. We also see pre- and post-master class conversations with the students, transcriptions of solos rolling across the screen as the solos are played and Giddins talking at length about the Heath Brothers' importance. Percy's and Jimmy's charm, humor, erudition and contrasting personalities come across strongly. This set is a highlight in an invaluable Artists House project.

Harvey Pekar, American Splendor: The Life And Times Of Harvey Pekar (Ballantine Books). Pekar, who died this month, mesmerized readers by transforming his ordinary life into comics for adults. Pekar wrote the stories. R. Crumb and a crew of other artists illustrated them to Pekar's specifications, in living black and white. His work led to the movie of the same name. I'm not sure that I'd go as far as some critics who compare him to Chekhov, but I'm not sure that I wouldn't. If Pekar's gritty ironies are an acquired taste, it's a taste that settles in quickly.

Harvey Pekar, American Splendor: The Life And Times Of Harvey Pekar (Ballantine Books). Pekar, who died this month, mesmerized readers by transforming his ordinary life into comics for adults. Pekar wrote the stories. R. Crumb and a crew of other artists illustrated them to Pekar's specifications, in living black and white. His work led to the movie of the same name. I'm not sure that I'd go as far as some critics who compare him to Chekhov, but I'm not sure that I wouldn't. If Pekar's gritty ironies are an acquired taste, it's a taste that settles in quickly.

This rhetorical padding is used by countless politicians and, it seems, nearly everyone interviewed or quoted in the news, from President Obama on down:

Take it out of virtually any sentence and you will lose no meaning. Example:

"The administration will keep a close watch on this, moving forward."

Getting rid of "moving forward;" now, that would be moving forward.

Of course, properly used, the phrase can be a source of inspiration...or amusement.

If everyone is moving forward together, then success takes care of itself— Henry Ford

Daring ideas are like chessmen moved forward; they may be beaten, but they may start a winning game— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

We will move forward, we will move upward, and yes, we will move onward— Dan Quayle

Jimmy Heath recently said  he's been hearing since he was a youngster that jazz is dying. The saxophonist and composer/arranger will be 84 in October. Joining him in discounting death rumors is a younger man, the veteran entrepreneur Todd Barkan, who runs the oddly named but vital Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola, a bastion of jazz in New York City. Barkan is preparing a fall festival designed to help insure the music's vitality by bringing together some of its wise elders with promising younger musicians. Pia Catton writes about the project in today's Wall Street Journal.

he's been hearing since he was a youngster that jazz is dying. The saxophonist and composer/arranger will be 84 in October. Joining him in discounting death rumors is a younger man, the veteran entrepreneur Todd Barkan, who runs the oddly named but vital Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola, a bastion of jazz in New York City. Barkan is preparing a fall festival designed to help insure the music's vitality by bringing together some of its wise elders with promising younger musicians. Pia Catton writes about the project in today's Wall Street Journal.

"We are reaching a critical stage in jazz music because we've lost a lot of people in the last few years," Mr. Barkan said. "Older artists teach a lot by example and the practice of jazz."

To learn of Barkan's plans for the festival and read all of the article, which includes an embedded video, go here.

Someone who identifies himself on YouTube as "liveacid" went to painstaking trouble to manufacture a video of Chet Baker and Paul Desmond playing "Autumn Leaves." The music track is from Baker's 1974 album She Was Too Good To Me. It was later reissued on the compilation Chet Baker & Paul Desmond Together. From disparate sources, the editor rounded up shots of Baker, Desmond, pianist Bob James, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Steve Gadd. You'll hear Hubert Laws' flute, but "liveacid" did not include shots of Laws.

"Autumn Leaves." The music track is from Baker's 1974 album She Was Too Good To Me. It was later reissued on the compilation Chet Baker & Paul Desmond Together. From disparate sources, the editor rounded up shots of Baker, Desmond, pianist Bob James, bassist Ron Carter and drummer Steve Gadd. You'll hear Hubert Laws' flute, but "liveacid" did not include shots of Laws.

The breaths Desmond and Baker take don't match those in the music, although they often come uncannily close. Pay attention to what fingers and drumsticks are doing in relation to the notes and you'll see the misses and near-misses. You never see the players together. The editor repeatedly recycles the same shots. Still, despite its flaws it's a clever job of digital cut and paste. It is reason enough to listen again to players who, as the liner notes of that compilation remind us, were wonderful together.

The breaths Desmond and Baker take don't match those in the music, although they often come uncannily close. Pay attention to what fingers and drumsticks are doing in relation to the notes and you'll see the misses and near-misses. You never see the players together. The editor repeatedly recycles the same shots. Still, despite its flaws it's a clever job of digital cut and paste. It is reason enough to listen again to players who, as the liner notes of that compilation remind us, were wonderful together.

Have a good weekend.

The Japanese have a longstanding love affair with jazz piano. Albums by jazz pianists sell consistently well in Japan. Leading pianists from around the world perform there in concerts and clubs. Indeed, the country has produced its own crops of world-class pianists, among them Toshiko Akiyoshi, Makoto Ozone, Kei Akagi, Junko Onishi and the current phenomenon Hiromi Uehara. A Japanese promoter organizes an annual tour called 100 Gold Fingers that features 10 prominent pianists in concert. The tour has included at one time or another Hank Jones, Roger Kellaway, Eddie Higgins, Jessica Williams, Junior Mance, Bill Charlap, Renee Rosnes, Cedar Walton and Ray Bryant, among many others.

No one in Japan is more committed to jazz piano than Tetsuo Hara. He records horn players and singers, too, but his Venus Records catalog is packed with CDs by some of the music's most prominent keyboard artists. Hara records many of them in New York under his supervision and that of the veteran producer Todd Barkan. His recordings have superior sound by first-rate engineers like Jim Anderson, David Darlington and Katherine Miller. For years, it was difficult and expensive for people outside Japan to acquire Venus records. Now, most of them are available in the US and elsewhere; at import prices, it's true, but bargain offers show up on some web sites. Although original compositions occasionally materialize on Venus albums, Mr. Hara's inclination is to have his artists record familiar music. In general, the results confirm that the song form offers endless possibilities, as even the famously iconoclastic saxophonist Archie Shepp demonstrates in his four Venus CDs.

under his supervision and that of the veteran producer Todd Barkan. His recordings have superior sound by first-rate engineers like Jim Anderson, David Darlington and Katherine Miller. For years, it was difficult and expensive for people outside Japan to acquire Venus records. Now, most of them are available in the US and elsewhere; at import prices, it's true, but bargain offers show up on some web sites. Although original compositions occasionally materialize on Venus albums, Mr. Hara's inclination is to have his artists record familiar music. In general, the results confirm that the song form offers endless possibilities, as even the famously iconoclastic saxophonist Archie Shepp demonstrates in his four Venus CDs.

Today's topic, however, is pianists.

Roland Hanna, Après Un Reve (Venus). In this exquisite little recital, the pianist bases his improvisations on music by Schubert, Fauré, Borodin, Chopin, Mozart, Dvořák, Mahler  and Anton Rubenstein. He recorded it less than two months before he died in November, 2002. Ron Carter's bass lines and Grady Tate's all-but-weightless drumming are perfect complements to Hanna, who reaches deep into the harmonic opportunites in pieces generations have loved for their melodies. Hanna's clarity of conception and lightness of touch are beautifully captured in this flawlessly engineered recording. Among the pleasures here are his chord substitutions as he makes his stately way through Mozart's indelible "Elvira Madigan" theme from the Op. 21 C Major Piano Concerto, the gravity of the trio's treatment of the second movement of Mahler's Symphony No 5 and—between those mostly solemn reflections—a Dvořák backbeat boogaloo on "Going Home" from The New World Symphony. This is a gem in Roland Hanna's discography.

and Anton Rubenstein. He recorded it less than two months before he died in November, 2002. Ron Carter's bass lines and Grady Tate's all-but-weightless drumming are perfect complements to Hanna, who reaches deep into the harmonic opportunites in pieces generations have loved for their melodies. Hanna's clarity of conception and lightness of touch are beautifully captured in this flawlessly engineered recording. Among the pleasures here are his chord substitutions as he makes his stately way through Mozart's indelible "Elvira Madigan" theme from the Op. 21 C Major Piano Concerto, the gravity of the trio's treatment of the second movement of Mahler's Symphony No 5 and—between those mostly solemn reflections—a Dvořák backbeat boogaloo on "Going Home" from The New World Symphony. This is a gem in Roland Hanna's discography.

Eddie Higgins, If Dreams Come True (Venus). It is an indication of Higgins's (1932-2009) popularity in Japan that the Venus catalog has 29 CDs under his name. Several of them, including this one from 2004, are trio or small band albums with bassist Jay Leonhart and drummer Joe Ascione. In accordance with the Hara dictum, all of the pieces but one are standards. That one, "Shinjuku Twilight," is an attractive A-minor theme that stimulates Higgins and Leonhart to some of their best soloing in an album in which both are at the tops of their games. "Standards" doesn't necessarily mean warhorses. "A Weekend in Havana" and "Into the Memory" are hardly overdone, and Higgins does them to a turn. It's good to hear Higgins caress Xavier Cugat's rarely performed 'Nightingale," convert "Days of Wine and Roses" into a "Killer Joe" soundalike and recall Django Reinhardt with a jaunty revival of "Minor Swing." Alec Wilder's "Moon and Sand" becomes a modified samba. The piece de resistance is "St. Louis Blues," with a boogie woogie component that may not have been intended as tribute to Earl Hines but would surely have generated one of Hines' thousand-watt smiles if he had heard it.

Ascione. In accordance with the Hara dictum, all of the pieces but one are standards. That one, "Shinjuku Twilight," is an attractive A-minor theme that stimulates Higgins and Leonhart to some of their best soloing in an album in which both are at the tops of their games. "Standards" doesn't necessarily mean warhorses. "A Weekend in Havana" and "Into the Memory" are hardly overdone, and Higgins does them to a turn. It's good to hear Higgins caress Xavier Cugat's rarely performed 'Nightingale," convert "Days of Wine and Roses" into a "Killer Joe" soundalike and recall Django Reinhardt with a jaunty revival of "Minor Swing." Alec Wilder's "Moon and Sand" becomes a modified samba. The piece de resistance is "St. Louis Blues," with a boogie woogie component that may not have been intended as tribute to Earl Hines but would surely have generated one of Hines' thousand-watt smiles if he had heard it.

Stanley Cowell, Dancers In Love (Venus). Cowell recorded this in 1999 with bassist Tarus Mateen and drummer Nasheet Waits, young lions beginning to make their names. He had already established his own reputation among musicians but to this day remains unfamiliar even to many dedicated jazz listeners. In part, that is because Cowell has dedicated much of the latter part of his career to jazz education, most recently with tenure at Rutgers  University. He is a complete pianist, capable not only of demonstrating the formidable technical aspects of Art Tatum but also of capturing the elusive subtleties and eccentricities of Thelonious Monk. In this album he employs his absolute command of the keyboard not in the service of display but of musical expression. Over the years, Charlie Parker's "Confirmation" has become a vehicle for speedsters. Cowell takes it at the pace of a leisurely walk, disclosing the lyricism concealed in its intriguing harmonies. In a brief exposition of Duke Ellington's "Dancers in Love," he gets inside Ellington's whimsy. He laces the cowboy song "Ole Texas" and a South African folk song with musical values and plays the whey out of Eubie Blake's "Charleston Rag," complete with bebop moments that make perfect sense. Cowell includes two originals, a bittersweet ballad called "I Never Dreamed" and "St. Croix," which sparkles with calypso verve. His inventiveness in Gershwin's "But Not For Me" is dazzling. This rarity of an album, like Cowell himself, should be better known.

University. He is a complete pianist, capable not only of demonstrating the formidable technical aspects of Art Tatum but also of capturing the elusive subtleties and eccentricities of Thelonious Monk. In this album he employs his absolute command of the keyboard not in the service of display but of musical expression. Over the years, Charlie Parker's "Confirmation" has become a vehicle for speedsters. Cowell takes it at the pace of a leisurely walk, disclosing the lyricism concealed in its intriguing harmonies. In a brief exposition of Duke Ellington's "Dancers in Love," he gets inside Ellington's whimsy. He laces the cowboy song "Ole Texas" and a South African folk song with musical values and plays the whey out of Eubie Blake's "Charleston Rag," complete with bebop moments that make perfect sense. Cowell includes two originals, a bittersweet ballad called "I Never Dreamed" and "St. Croix," which sparkles with calypso verve. His inventiveness in Gershwin's "But Not For Me" is dazzling. This rarity of an album, like Cowell himself, should be better known.

Manfred Eicher has been successful with his ECM label not by constantly taking the pulse of the public and the record industry but by recording music he likes. That is an oversimplification, but not much of one. In the British newspaper The Guardian, Richard Williams has a piece about Eicher and his 40 years at the helm of the company he founded. Near the top of the article, he writes:

To its many admirers, ECM stands for a certain meditative, introspectiveapproach to playing and listening. Its albums - about a thousand of them to date - are recorded and packaged with a deliberate refinement, once upsetting to those who concluded that Eicher had somehow squeezed the vitality from the jazz he professed to love, contaminating it by an association with his north European sensibility.

That argument seems to have been won.

Williams goes on to make the case, in part with quotes like this from Eicher:

"For me it's very good to bring the demands of written music - phrasing, intonation, dynamics - to improvisational recording, where the approach is looser and more spontaneous. And vice versa, to bring some of the spirit of an improvised music session into a recording of written music, to get some empathy into it, so that it doesn't become an academic-circle record. I'm trying to make an exchange, to bring one to the other."

To read the whole thing, go here.

This was first a Rifftides post on March 24, 2006.

Thanks to Bill Reed and David Ehrenstein for calling this to our attention.

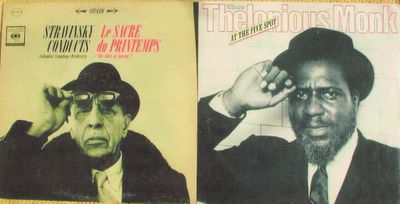

The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees oneself. And the arbitrariness of the constraint serves only to obtain precision of execution. —Igor Stravinsky

At this time the fashion is to bring something to jazz that I reject. They speak of freedom. But one has no right, under pretext of freeing yourself, to be illogical and incoherent by getting rid of structure and simply piling a lot of notes one on top of the other. —Thelonious Monk

Richie Kamuca & Lee Konitz, Live at Donte's 1974 (Cellar Door)

It's a hoot to hear the saxophonists channel their hero Lester Young in this recently discovered session recorded at the lamented Los Angeles club. "Lester Leaps In" begins and ends as a unison duet, complete with stop-time breaks,  reproducing Young's 1939 solo on the master take of the piece with Count Basie's Kansas City Seven. In their own solos, Kamuca and Konitz leave no doubt about where they came from. Kamuca, the tenor player, is clearest in his fealty to Young. Konitz, on alto, is more abstract in his Prezcience, but it has always been a major element in his work. The other tunes are standards in the gig books of musicians of Kamuca's (1930-1977) and Konitz's (1927- ) generation—"Just Friends," "Star Eyes," "All The Things You Are" and Bobby Troup's "Baby, Baby All The Time." Solos are long and exploratory; the shortest track is 7:41. The set has the exhilaration, rough edges, chance-taking and surprises that make for satisfying live performance.

reproducing Young's 1939 solo on the master take of the piece with Count Basie's Kansas City Seven. In their own solos, Kamuca and Konitz leave no doubt about where they came from. Kamuca, the tenor player, is clearest in his fealty to Young. Konitz, on alto, is more abstract in his Prezcience, but it has always been a major element in his work. The other tunes are standards in the gig books of musicians of Kamuca's (1930-1977) and Konitz's (1927- ) generation—"Just Friends," "Star Eyes," "All The Things You Are" and Bobby Troup's "Baby, Baby All The Time." Solos are long and exploratory; the shortest track is 7:41. The set has the exhilaration, rough edges, chance-taking and surprises that make for satisfying live performance.

Support for the two Ks is by the solid L.A. rhythm section of pianist Dolo Coker, bassist Leroy Vinnegar and drummer Jake Hanna, all of whom solo to great effect. Vinnegar goes beyond his customary walking bass for a couple of bowed solos and a bit of unexpected wildness in his "Lester Leaps In" solo, to the evident amusement of his colleagues and the audience. Coker, an under-recognized high achiever among Bud Powell admirers, has impressive moments throughout. Hanna cooks along, fueling the swing. Toward the end of the last track, "Lester," he finally takes a solo. What he saved up is worth the wait. The sound of this session, exhumed from reel-to-reel tapes, won't turn Rudy Van Gelder green with envy, but it's perfectly acceptable; you can plainly hear what everyone is doing. Unearthing and releasing it is a feather in the cap of Cellar Door's Bill Reed. On the CD box, it says, "Limited Edition." The 300 copies probably won't last long because there is nothing limited about the music.

Here is the new batch of short reviews —micro-reviews, perhaps—in which the Rifftides staff acknowledges some of the CDs that have attracted our attention lately. It would be impossible to hear all of every album that shows up. Even sampling a majority of them is a challenge. Evidence: these are some, only some, of the fairly recent arrivals. Whoever said jazz is dying hasn't talked to my FedEx, UPS and USPS deliverymen.

Pharez Whitted, Transient Journey (Owl). In his liner notes, Neil Tesser writes of trumpeter Whitted's playing, "the spirit of Freddie Hubbard hovers nearby." It certainly does. With his facility and fat, even sound, Whitted does hard bop a la Hubbard to a turn. His own spirit seems to materialize most clearly in his slower pieces, notably the title tune and "Sunset on the Gaza". On flugelhorn, he is reflective in "Until Tomorrow Comes," with its samba inflection. Whitted's sextet includes a rhythm section of fellow Chicagoans. In the front line he has the masterly guitarist Bobby Broom and saxophonist Eddie Bayard, who is from Jamaica by way of Ohio and fits nicely into Chicago's tough tenor tradition.

and fat, even sound, Whitted does hard bop a la Hubbard to a turn. His own spirit seems to materialize most clearly in his slower pieces, notably the title tune and "Sunset on the Gaza". On flugelhorn, he is reflective in "Until Tomorrow Comes," with its samba inflection. Whitted's sextet includes a rhythm section of fellow Chicagoans. In the front line he has the masterly guitarist Bobby Broom and saxophonist Eddie Bayard, who is from Jamaica by way of Ohio and fits nicely into Chicago's tough tenor tradition.

Jacám Manricks, Trigonometry (Posi-Tone). A year after his stimulating Labyrinth (see the Rifftides review here), the young Australian based in New York divests himself of the chamber orchestra and pares down to a quartet, adding guest horns  on three pieces. The writing skills he displayed on the previous album are in evidence in the smaller context. Using trompe l'oreille harmonies, Manricks voices his alto saxophone, Scott Wendholt's trumpet and Alan Ferber's trombone to sound like a larger ensemble. "Cluster Funk," as audacious as its title, is a prime case in point. It has a beautifully shaped Wendholt solo. As for Manricks' own playing, it ranges from heart-on-the-sleeve lyricism in "Mood Swing" to a sort of post-Konitz earnestness in "Slippery" to bounds and leaps reminiscent of Eric Dolphy in, among other pieces, Dolphy's "Miss Ann." Pianist Gary Versace, bassist Joe Martin and drummer Obed Calvaire are the well-matched rhythm section.

on three pieces. The writing skills he displayed on the previous album are in evidence in the smaller context. Using trompe l'oreille harmonies, Manricks voices his alto saxophone, Scott Wendholt's trumpet and Alan Ferber's trombone to sound like a larger ensemble. "Cluster Funk," as audacious as its title, is a prime case in point. It has a beautifully shaped Wendholt solo. As for Manricks' own playing, it ranges from heart-on-the-sleeve lyricism in "Mood Swing" to a sort of post-Konitz earnestness in "Slippery" to bounds and leaps reminiscent of Eric Dolphy in, among other pieces, Dolphy's "Miss Ann." Pianist Gary Versace, bassist Joe Martin and drummer Obed Calvaire are the well-matched rhythm section.

Dino Saluzzi, El Encuentro (ECM). The venerable bandoneónista combines with the strings of the Metropole Orchestra in a suite that alternates languor and drama. Saluzzi marinates four long tracks in the sadness and passion that characterize the Argentine tango tradition, accenting them with contrasting bursts of dance-like joy from his bandoneon. His saxophonist brother Feliz and cellist Anja Lechner—each with a rich, roomy tone—also solo in this beautifully recorded concert performance in the Netherlands. Any piece called "Miserere" obligates itself to carry the emotional weight the title implies. Saluzzi's "Miserere," with the profundity of his bandoneon solo section, meets the obligation. Like all lasting music, Saluzzi's work discloses new facets with each hearing.

Saluzzi marinates four long tracks in the sadness and passion that characterize the Argentine tango tradition, accenting them with contrasting bursts of dance-like joy from his bandoneon. His saxophonist brother Feliz and cellist Anja Lechner—each with a rich, roomy tone—also solo in this beautifully recorded concert performance in the Netherlands. Any piece called "Miserere" obligates itself to carry the emotional weight the title implies. Saluzzi's "Miserere," with the profundity of his bandoneon solo section, meets the obligation. Like all lasting music, Saluzzi's work discloses new facets with each hearing.

Trisha O'Brien, Out Of A Dream (Azica). Ms. O'Brien sings in tune, swings lightly with a good time feel, understands the meaning of lyrics, chooses fine songs and doesn't scat. She and  producer Elaine Martone know how to put a band together. Lewis Nash is the drummer, Peter Washington the bassist. On piano is the sensitive accompanist Shelly Berg, who also did the arrangements. Ken Peplowski plays tenor saxophone on three tracks and has a peach of a solo on "Taking a Chance on Love." The songs are from what reviewers are required to call The Great American Songbook (anyone with a better name is welcome to submit it). That means we get Porter, Loesser, Berlin, and Burke and Van Heusen, among others. There are latterday entries by Joni Mitchell and Alan and Marilyn Bergman. In "Everybody Loves My Baby," Ms. O'Brien manages to be both sinuous and saucy, with Peplowski commenting on tenor sax and Washington in a walking solo right out of the Leroy Vinnegar playbook.

producer Elaine Martone know how to put a band together. Lewis Nash is the drummer, Peter Washington the bassist. On piano is the sensitive accompanist Shelly Berg, who also did the arrangements. Ken Peplowski plays tenor saxophone on three tracks and has a peach of a solo on "Taking a Chance on Love." The songs are from what reviewers are required to call The Great American Songbook (anyone with a better name is welcome to submit it). That means we get Porter, Loesser, Berlin, and Burke and Van Heusen, among others. There are latterday entries by Joni Mitchell and Alan and Marilyn Bergman. In "Everybody Loves My Baby," Ms. O'Brien manages to be both sinuous and saucy, with Peplowski commenting on tenor sax and Washington in a walking solo right out of the Leroy Vinnegar playbook.

More reviews to come. Soon, I hope.

In a doomed attempt to stay abreast of the torrent of new releases flooding into Rifftides world headquarters, the staff is feverishly preparing a series of brief reviews; perhaps "alerts" would be a better word. It is our intention to begin posting them tomorrow or the next day. Even in the digital age, however, listening is a linear proposition, so bear with us. We can't just inhale the music, you know (no substance gags, please).

reviews; perhaps "alerts" would be a better word. It is our intention to begin posting them tomorrow or the next day. Even in the digital age, however, listening is a linear proposition, so bear with us. We can't just inhale the music, you know (no substance gags, please).

Oh, that was a substance gag.

Watch this space.

Ending this Rifftides mini-series of videos from the Dave Brubeck Quartet's 1964 appearance on Belgian television is—what else?—the number that became a popular hit in a best-selling album and for Desmond, its composer, an annuity that by terms of his will is still funneling large amounts of money to the Red Cross. The quartet included it in all of their concerts around the world, lest there be disappointed audiences. This version has a brief solo from Desmond, an elegiac one from Brubeck, and Morello more subdued and thoughtful than he sometimes was in this show piece. There are cast and crew credits at the end of this beautifully produced television episode.

A new three-day jazz event joins the roster of festivals that enliven Europe each summer. A musician heads this one. The Swedish pianist Jan Lundgren is organizing an early August festival in his hometown, the historic seaside village of Ystad.

In addition to Lundgren's trio, the headliners include Benny Golson, Toots Thielemans, Richard Galliano, Jacob Fischer and Paolo Fresu. To see the program schedule and other information, go here.

In addition to Lundgren's trio, the headliners include Benny Golson, Toots Thielemans, Richard Galliano, Jacob Fischer and Paolo Fresu. To see the program schedule and other information, go here.

Inspired by the new Bill Charlap-Renee Rosnes CD (see the review), I sent the Rifftides staff in search of other piano duos. They found this.

Rifftides reader Allen Mezquida writes:

It seems that Pekar had a greater perception about jazz than many musicians I know. He listened with a rich open mind and a big heart.

I created this animation for him. It was finished about a week before

he died.

Allen Mezquida animates films and plays alto saxophone in Los Angeles.

Harvey Pekar died this week at the age of 70. He will, inevitably, be more widely remembered for his seriously adult American Splendor comics and the movie they inspired than for his jazz criticism. As a writer about music he was—no surprise—eccentric and uneven but at his best wrote with precision and frankness about what he heard in his careful listening. Here is the conclusion of his Austin Chronicle review of the reissue of the Miles Davis Cellar Door Sessions.

remembered for his seriously adult American Splendor comics and the movie they inspired than for his jazz criticism. As a writer about music he was—no surprise—eccentric and uneven but at his best wrote with precision and frankness about what he heard in his careful listening. Here is the conclusion of his Austin Chronicle review of the reissue of the Miles Davis Cellar Door Sessions.

Maybe Miles was thinking of himself more as the lead voice of a collectively improvising ensemble than a soloist. He plays in fits and starts, screaming, improvising complex but sloppily executed runs, not making good use of wah-wah effects. His efforts don't hold together well. The loose group concept might be prime suspect in Davis' cliché-filled performance, but there's (Keith) Jarrett, member of the same group, playing so well. Jazz fans tend to think of and evaluate Davis' fusion recordings as a whole, but actually there's a wide variation in their quality, and that should be kept in mind when purchasing them.

To read the whole review, go here.

Pekar was infatuated with some of the least tethered free jazz. Writing about his avant garde heroes he sometimes went as far out as they did. Yet, he was capable of an open mind and an even keel, as in this observation from a review of the box set reissue that includes Ghosts, saxophonist Albert Ayler's 1964 collaboration with Sonny Murray, Don Cherry and Gary Peacock.

Here we have characteristic and mature performances by Ayler. In evidence are his honks, above-the-normal-upper-register screams and squeals, lines played so fast they seem to be a blur of notes and a huge vibrato. His original compositions are also unique, so archaic sounding that they seem modern. The influence of both church and martial music is apparent in them.

Unlike some critics of his avant leanings who categorically rejected music of the so-called West Coast movement, Pekar learned to understand Chet Baker.

When I was exposed to jazz in the mid-Fifties, it was as a fan of robust hard bop, musicians like Sonny Rollins and Clifford Brown. The popular West Coast jazz of that time seemed to lack vigor and as a whole was less progressive. Baker was suspect because his trumpet playing was so quiet and introverted; it seemed to lack strength. But after listening to him for years I had to admit that he had a rich melodic imagination, putting his solos together smoothly and swinging gracefully. I grew to like his small, velvety tone, and eventually came to the conclusion that he was an original and admirable performer.

Readers will miss Pekar most of all for the penetrating honesty and sardonic humor of his social observations as a comics writer. They should not overlook his value as a jazz critic. Of the Pekar obituaries I have seen, by far the most comprehensive is the one by William Grimes in The New York Times.

More or less from the beginning of their association, Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond had an affinity for blues in minor keys. Three that achieved success to the point of indelible identification with them were "Balcony Rock," first recorded in Jazz Goes To College (1954), the same theme recycled as "Audrey" for Brubeck Time (1956), and "Koto Song" from Jazz Impressions Of Japan (1964). "Koto Song" was a new entry in the quartet's repertoire when they played it on television in Belgium in '64. This is the group usually referred to as the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet, with Eugene Wright, bass, and Joe Morello, drums.

Next time: the final installment of this series of DBQ pieces from Belgium.

Bill Kirchner writes:

Recently, I taped my next one-hour show for the "Jazz From The Archives" series. Presented by the Institute of Jazz Studies, the series runs every Sunday on WBGO-FM (88.3).

Gene Lees (1928-2010) was one of jazz's foremost essayists and biographers. And he wrote liner notes for a number of classic jazz albums: John Coltrane's Ballads, Bill Evans' Conversations With Myself and At The Montreux Jazz Festival, The Individualism of Gil Evans, and Getz/Gilberto, among others.

Lees also wrote memorable lyrics to music by Antonio Carlos Jobim, Bill Evans, Milton Nascimento, Lalo Schifrin, Roger Kellaway, Charles Aznavour, Manuel DeSica, and others. We'll hear performances of some of those songs--some well-known, others obscure--by Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Jackie Cain, Rita Reys, Nancy Wilson, and Lees himself.

The show will air this Sunday, July 18, from 11 p.m. to midnight, Eastern Daylight Time. If you live outside the New York City metropolitan area, WBGO also broadcasts on the Internet at www.wbgo.org.

To see Rifftides on Gene Lees, and readers' comments, go here.

From a DBQ television appearance in Europe, we have the piece that served as the quartet's concert opener for more than a decade. First, a couple of observations, one from me, one from Eugene Wright:

From me: Whoever decreed that white men can't play the blues never really listened to Desmond and Brubeck personalize the idiom as they do in their solos here.

Gene's observation is a quotation in a book about Desmond. The first part of it applies to his relationship with Morello from the beginning of their time together, when Wright joined Brubeck in early 1958.

Right away, Joe and I were as one. It was like Jo Jones and Walter Page with Count Basie. It was right from the beginning. Joe Morello and I locked up immediately. Joe's out of New York and he had that thing--Ben Webster and all those guys loved him because he had that little extra thing you need. When musicians used to ask me how I could play with that band, I told them they weren't listening. I told them I was the bottom, the foundation; Joe was the master of time; Dave handled the polytonality and polyrhythms; we all freed Paul to be lyrical. Everybody was listening to everybody. It was beautiful. Those people who couldn't accept it were looking, not listening.

That was the major blues for this mini-series. Tomorrow, the minor blues.

Dr. Lonnie Smith, Spiral (Palmetto). Smith is a doctor in the same way that Captain Beefheart is a captain, but I'm willing to concede him the title because he knows how to make you feel good. Of the  generation of post-bop organists who followed Jimmy Smith, he survived his near-namesake Lonnie Liston Smith, Don Patterson, Jimmy McGriff, Richard "Groove" Holmes, Shirley Scott, Jack McDuff and Jimmy Smith himself. At 68, he carries on the tradition employing the Hammond B-3 not only as a blues dynamo—although he is capable of that—but also caressing melodies, as in his title composition and an unlikely choice, the 1963 international pop hit "Sukiyaki," which he somehow manages to divest of its corn.

generation of post-bop organists who followed Jimmy Smith, he survived his near-namesake Lonnie Liston Smith, Don Patterson, Jimmy McGriff, Richard "Groove" Holmes, Shirley Scott, Jack McDuff and Jimmy Smith himself. At 68, he carries on the tradition employing the Hammond B-3 not only as a blues dynamo—although he is capable of that—but also caressing melodies, as in his title composition and an unlikely choice, the 1963 international pop hit "Sukiyaki," which he somehow manages to divest of its corn.

Smith exemplifies his tasteful treatment of song book standards in a medium-tempo stroll through Frank Loesser's "I've Never Been in Love Before," making thoughtful use of space to let the organ and the listener breathe. With Jamire Williams's drums roiling and guitarist Jonathan Kreisbserg playing ostinato patterns, Smith makes Rodgers and Hart's "I Didn't Know What Time it Was" an exercise in compelling forward motion. He flirts with ¾ time in "Sweet and Lovely" without fully committing to it. The resulting rhythmic tension develops a push that energizes his and Kreisberg's solos. "Beehive," with its buzzing air of menace, would be perfect for the opening credits in a Stanley Kubrick movie starring Jack Nicholson. Smith takes Slide Hampton's "Frame for the Blues" at a metronome pace of about 56 that would seem glacial if he and his sidemen didn't invest it with powerhouse oomph and blues feeling that make it, to these ears, the album's stealth piece de resistance.

This time, Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond, Gene Wright and Joe Morello play "In Your Own Sweet Way." Because of the quality of the song, the quartet's popularity and the Miles Davis seal of approval, by the time of this performance in 1964 it was a jazz standard. Attention, tune detectives: Brubeck's Matt Dennis quote suggests that he might have been thinking of disbanding, but the quartet's dissolution was five years away.

For the first part of this mini-series, see the July 10 entry below. There is more to come.

Every traveling jazz soloist knows that playing with pickup sidemen, or sidewomen, is a game of chance. There is a chance that there will be a disaster, a chance that the temporary colleagues will be adequate, and a long outside chance that something special will happen.

Thursday night at The Seasons in Yakima, Washington, Emil Viklický hit that outside chance. The Czech pianist and composer was in the Pacific Northwest for the premier of his Double Concerto for Harp, Oboe and String Orchestra at the national conference of the American Harp Society. Following the performance, he made the trip from Tacoma across the Cascade mountains to The Seasons for a trio concert in that acoustic marvel of a small nonprofit performance hall.

conference of the American Harp Society. Following the performance, he made the trip from Tacoma across the Cascade mountains to The Seasons for a trio concert in that acoustic marvel of a small nonprofit performance hall.

Pat Strosahl, the Seasons founder, engaged bassist Clipper Anderson, who drove in from Montana on his way back home to Seattle. The drummer was Don Kinney, head of the percussion section of the Yakima Symphony Orchestra and a seasoned jazz player. Kinney has distinguished himself at Seasons concerts with other visiting leaders including pianists Alan Broadbent and the Swedish star Jan Lundgren. Anderson and Kinney knew of one another's work but had never played together. Viklický had played with neither. Viklický had e-mailed Anderson lead sheets for a few of his compositions

Because of Anderson's late-afternoon arrival following his long drive, the three had time  only for a 45-minute rehearsal. They ran through a few standards, and complex originals based directly on Moravian folk songs or on music by Czech national hero Leoš Janáček. Janáček is one of the great classical interpreters of the Moravian musical tradition that also inspires Viklický.

only for a 45-minute rehearsal. They ran through a few standards, and complex originals based directly on Moravian folk songs or on music by Czech national hero Leoš Janáček. Janáček is one of the great classical interpreters of the Moravian musical tradition that also inspires Viklický.

At the concert, it was clear after the opening chorus of Cole Porter's "Everything I Love" that this might turn out to be a memorable evening. It was evident not only because of the single-mindedness of the trio's swing but also because of Viklický's grin, which made frequent appearances. Introducing his adaptation of the folk tune "A Bird Flew Over," he called Kinney and Anderson "my new Moravian musicians." Several of the pieces were from Viklický's latest trio record, Sinfonietta, with bassist George Mraz and drummer Lewis Nash. The live versions with Anderson and Kinney compared favorably. It was not just a matter of their considerable technique. The three connected, locked in, listened and reacted to one another on the same wave length. At the end of the concert, when the cheering stopped, the pianist was effusive in his compliments to his new Moravians.

and Kinney compared favorably. It was not just a matter of their considerable technique. The three connected, locked in, listened and reacted to one another on the same wave length. At the end of the concert, when the cheering stopped, the pianist was effusive in his compliments to his new Moravians.

In an evening of high points, the highest was the Viklický piece he tied to his delighted discovery that he was in the heart of Washington State's celebrated wine country. He explained that "Wine, Oh Wine" grew out of his and his fellow Moravians' love of a folk song often sung on special occasions, including weddings and funerals. It concerns the dilemma of whether to drink red or white wine. The correct Moravian answer, Viklický said, is "both." Then, he, Anderson and Kinney celebrated that idea with a vintage performance that matched or exceeded the song's natural exuberance. Swing doesn't come much harder than what they achieved on "Wine, Oh Wine." Three skilled musicians, the common language of jazz and the chemistry that developed in a chance encounter had, indeed, produced a memorable evening. Viklický's grin migrated to every face in the house.

Unfortunately, there is no video from the Yakima concert, but here is Viklický with his Czech trio, bassist Frantisek Uhlir and drummer Laco Tropp. The tune is Ray Brown's "Buhaina, Buhaina."

Concert videos from out of the past continue to materialize on the internet. Recent emanations include several pieces from a 1964 appearance in Belgium by the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet. The excellent picture and sound quality and the absence of applause suggest that the performances were in a television broadcast. Over the next few days, we will bring you several of the clips, beginning with "Three to Get Ready." It has a couple of rough edges, but with a band that had this much fun, who cares? Here is an unexpected bit of living history with Brubeck, Paul Desmond, Gene Wright and Joe Morello. Desmond's "Auld Lang Syne" gag was still fresh enough to amuse his co-conspirators.

Joya Sherrill, the singer who died in late June at the age of 85, joined Duke Ellington and his Orchestra in 1942 following her high school graduation. One of her features through the mid-forties was the Billy Strayhorn-Rex Stewart collaboration "Kissing Bug." The song received a good deal of radio air play and in its V-disc version became a favorite of the troops as World War Two wound down. Here is the V-disc performance, followed by a brief take on Ellington's "Carnegie Blues." Ben Webster's successor in the band, Al Sears, is the tenor saxophone soloist.

his Orchestra in 1942 following her high school graduation. One of her features through the mid-forties was the Billy Strayhorn-Rex Stewart collaboration "Kissing Bug." The song received a good deal of radio air play and in its V-disc version became a favorite of the troops as World War Two wound down. Here is the V-disc performance, followed by a brief take on Ellington's "Carnegie Blues." Ben Webster's successor in the band, Al Sears, is the tenor saxophone soloist.

Ms. Sherrill worked off and on with Ellington for most of her performing life. She was with the Benny Goodman band that toured the Soviet Union in 1962. In the 1970s, she hosted the childrens program Time For Joya on one of my alma maters, WPIX-TV in New York City.

Jazz developed in the United States, but it has long been an international music and many of its most prominent players are from other countries. The Dane Svend Asmussen is coming in for even more attention than usual lately. Attention is far from new in the career of the remarkable violinist, but when a musician is halfway through his tenth decade and still swinging, he gets extra notice. One who notices is Will Friedwald. He writes about Asmussen in today's Wall Street Journal. Here's the first paragraph.

Jazz developed in the United States, but it has long been an international music and many of its most prominent players are from other countries. The Dane Svend Asmussen is coming in for even more attention than usual lately. Attention is far from new in the career of the remarkable violinist, but when a musician is halfway through his tenth decade and still swinging, he gets extra notice. One who notices is Will Friedwald. He writes about Asmussen in today's Wall Street Journal. Here's the first paragraph.

"How are you doing?" That's normally an innocuous question, except when you happen to be asking a 94-year-old violinist who is probably the oldest currently active major jazz musician in the world. "I do very well," answers Svend Asmussen, speaking by phone from his home in a Danish fishing village outside of Copenhagen, "considering my extremely advanced age."

To read the whole thing, go here. For a Rifftides review of two Asmussen albums, go here.

Regarding the "Where We Are" item below, Rifftides reader Cyril Moshkow writes

Looks like the info is not exactly complete, as many people readthrough RSS aggregation (which does not include logging in.) For instance, I am reading Rifftides in Moscow, Russia, but almost never directly -- it is aggregated in my blogroll.

That's a good point, Cyril. Unfortunately the site meter doesn't calculate RSS deliveries, so we cannot know how many people sign on by that means.

Be sure to visit Mr. Moshkow's excellent site, Russian Jazz—DR

Rifftides readers are all over the world, more concentrated in some countries than others. We don't hear much from Cuba or Outer Mongolia, for instance. Here is a list of nations where readers have logged on to Rifftides in the past week.

Australia

![]()

By most accounts, there are 195 countries on earth. Sixteen are represented in that list. The Rifftides staff hopes that people in the remaining 179 will join us. Wherever you are, we're glad to have you along. If you find something here that interests or stimulates you, please send your comments.

Here's a story from the BBC:

(July 1) Queen unveils statue of Canadian jazz great PetersonThe Queen has unveiled a life-size bronze statue of Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson during the latest stage of her visit to the country.She was joined by the musician's family for the ceremony at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa.

During his life, Peterson recorded with jazz greats like Ella Fitzgerald and Charlie Parker. He played for the Queen a few years before his death in 2007.The Queen and Prince Philip are on a nine-day visit to Canada.

The sculpture depicts Peterson sitting at his famous piano - which had extra keys added - in a bow tie and waistcoat. There is space on the seat beside him for passers-by to sit down.

His widow Kelly said: "Oscar would be very humbled by it and also very, very pleased to know how much people loved what he did and care about him. And the fact that Her Majesty and Prince Philip are here is an extra special layer - he loved them both."

Dressed in a turquoise hat and coat, the Queen later visited the Museum of Nature and planted a tree in the governor general's garden.

Rifftides reader John Fielding writes from Australia:

I am currently reading and enjoying your book about Paul Desmond. I am a lifelong DB and PD follower after seeing them play in Brisbane, Australia, in 1960.

Congratulations on a great contribution to jazz history and the stories and colors of the era of the 50's.Amazing that 'Take Five' has been so widely recorded. I thought you might be interested to know that I recently heard 'Take Five' on a stay in Beijing. There is a very popular group known as the Twelve Girls (actually, there are thirteen of them and I suspect that the band name has something to do with a pun to which all Chinese speakers are addicted). Their forte is playing Western classical and some pop music on Chinese traditional instruments. They also have an extensive Chinese classical repertoire. They do an interesting version of the song. I subsequently found the song on one of their CDs.

I think that Paul would approve - particularly as the twelve (thirteen?) girls are very attractive as well as talented. Interesting that the erhu (one stringed fiddle that looks like a coffee can with a long handle) actually produces a lovely full-bodied cello style note that suits the song very well.

Thank you and all the best from Australia.John Fielding

You're welcome, John. And thank you, but wait a minute; four of those 12 (or 13) girls seem to be guys. Could that be the source of the pun?

Jason Moran, Ten (Blue Note)

It is possible that Jason Moran is the messianic paragon that the tide of jump-on-the-Bandwagon critical enthusiasm proclaims him. I am willing to cede that judgment to the leavening passage of time. It is no abandonment of restraint, however, to agree that Moran is an original thinker and a hell of a piano player. If there were no other reason to make that concession, I would be convinced by his treatment of the late Jaki Byard's "To Bob Vatel of Paris." Byard recorded the variation on "I Got Rhythm" changes in his breath-taking 1972 solo LP There'll Be Some Changes Made. The album was briefly reissued on CD as Empirical. Then, absurdly, it was allowed to go out of print and is now available only at outrageous collectors prices.

It is possible that Jason Moran is the messianic paragon that the tide of jump-on-the-Bandwagon critical enthusiasm proclaims him. I am willing to cede that judgment to the leavening passage of time. It is no abandonment of restraint, however, to agree that Moran is an original thinker and a hell of a piano player. If there were no other reason to make that concession, I would be convinced by his treatment of the late Jaki Byard's "To Bob Vatel of Paris." Byard recorded the variation on "I Got Rhythm" changes in his breath-taking 1972 solo LP There'll Be Some Changes Made. The album was briefly reissued on CD as Empirical. Then, absurdly, it was allowed to go out of print and is now available only at outrageous collectors prices.

In his tenth CD on Blue Note, Moran takes his cue for "Vatel" from Byard, with whom he studied. He begins alone, parahrasing and bending the stride style Byard used in the piece. Then, Moran and his longtime sidemen, bassist Tarus Mateen and drummer, Nasheet Waits work their way into the kind of swirling, nearly aharmonic improvisation of which Byard was a master. Standard metric time all but goes out the window for a while, but swing does not. When they have wrapped up the tune six minutes later, they have run it through a kaleidoscope of shifting shapes and colors.

but swing does not. When they have wrapped up the tune six minutes later, they have run it through a kaleidoscope of shifting shapes and colors.

There is much else in the CD to enjoy or wonder at. Moran manages to combine his loves of hip-hop and Thelonious Monk in "Crepuscle With Nellie." He expands on the spirit, energy and blues core of Leonard Bernstein's "Big Stuff," and melds it into the next track, "Play to Live," which Moran wrote with the late Andrew Hill, another of his teachers. "Pas de Deux," an unaccompanied piece with the mystery and solemnity of a nocturne, is from a ballet for which Moran wrote the music. There are fast and slow versions of "Study No. 6," one of the eccentric composer Conlon Nancarrow's pieces for player piano. "The Subtle One" lives up to its title with reflective piano and bass musings and finely etched brush and cymbal work by Waits.

"Gangsterism Over 10 Years," bluesy and packed with references to pop dance idioms, is the latest iteration of a theme sketch that the trio, known as The Bandwagon, has been developing since its founding. The bonus track, hidden at the end and not included in the CD's play list, is "Nobody," the signature song of Bert Williams, a hero of black vaudeville memorialized in 1940 by Duke Ellington in "A Portrait of Bert Williams." Moran, Mateen and Waits handle it with the mixture of tenderness, exuberance and irony that characterized Williams' own approach to the song.

"Nobody" is not all that's hidden. There is no clue to the musical value of embedding samples of rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix's feedback behind the trio's lovely musings in the track called "Feedback Pt. 2." They don't do a "Feedback Pt. 1." That's okay.

Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.—Benjamin Franklin

America will never be destroyed from the outside. If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves. —Abraham Lincoln

In New Orleans, street musicians in the French Quarter are a tourist attraction. According to city law, they are also a nuisance. The contradiction has roots in jazz history and city tradition. It puts police and the administration of the new mayor, Mitch Landrieu, between residents of the Quarter who want to get some sleep and musicians like these outside Jackson Square who want to make a living or, at least, pick up a few bucks. On the web site truthdig, Artsjournal.com blogger Larry Blumenfeld posted an exhaustive report about the controversy. He connects it to situations portrayed in the hot new cable television series Treme. Here is an excerpt that grew out of his conversation with a civil rights lawyer named Mary Howell.

On the web site truthdig, Artsjournal.com blogger Larry Blumenfeld posted an exhaustive report about the controversy. He connects it to situations portrayed in the hot new cable television series Treme. Here is an excerpt that grew out of his conversation with a civil rights lawyer named Mary Howell.

Section 66-205 could be construed to prohibit a lone guitarist strumming on a corner or someone playing harmonica to no one in particular in the street. Same for Section 30-1456, which, curiously, pertains to a stretch of Bourbon Street filled mostly with bars that blast recorded music well into the night. Add to this, Howell explains, that in 1974 the city passed a zoning ordinance that actually prohibits live entertainment in New Orleans, save for spots that are either grandfathered in or specially designated as exceptions. Those interior shots in "Treme" faithfully depicting the vibe at Donna's Bar & Grill and Bullet's Sports Bar? Grandfathered in, or they'd be technically illegal. Current zoning restrictions could, without much of a stretch, be construed to prohibit band rehearsals, parties with musical entertainment, even poetry readings. "It's a draconian ordinance," says Howell, "and a blanket over the city." The very idea is mind-boggling to those who live outside New Orleans: a city whose image is largely derived from its live musical entertainment essentially outlawing public performance through noise, quality-of-life, and zoning ordinances.

To read Blumenfeld's entire piece, go here.

Vincent Herring & Earth Jazz, Morning Star (Challenge). The rhythm section known as Earth Jazz is electrified,  funkified and synthesized. Collaborating with them, Herring looks back to the heyday of '60s and '70s soul, with stylistic references to Herbie Hancock, early Weather Report and tinges of Azymuth and The Crusaders. His customary power and tonal perfection on alto and soprano saxophones are intact, even as he adheres to the limitations of the setting. The title tune eases up on the back beat, allowing Herring the balladry at which he excels. It's a welcome break from the funk formula, as are his echoes of Hank Crawford, and Anthony Wonsey's acoustic piano work in the concluding "You Got Soul."

funkified and synthesized. Collaborating with them, Herring looks back to the heyday of '60s and '70s soul, with stylistic references to Herbie Hancock, early Weather Report and tinges of Azymuth and The Crusaders. His customary power and tonal perfection on alto and soprano saxophones are intact, even as he adheres to the limitations of the setting. The title tune eases up on the back beat, allowing Herring the balladry at which he excels. It's a welcome break from the funk formula, as are his echoes of Hank Crawford, and Anthony Wonsey's acoustic piano work in the concluding "You Got Soul."

In its entirety, this is an item from "The Reliable Source" blog in The Washington Post this week:

Medvedev goes for the record: Jazz and rock music, that is

While Russian President Dmitry Medvedev was in Washington with President Obama onofficial business, his staff went on a more personal quest: music for his vinyl collection.

Two Russian women who said they worked for Medvedev walked into Som Records on 14th Street Thursday looking for Duke Ellington, B.B. King and Jimi Hendrix recordings -- Medvedev, 44, is a big jazz and rock fan and collects rare records. Owner Neal Becton told us he was out of Ellington discs, but sold the women three Hendrix records, two by King, plus music by Gil Evans, Blossom Dearie and Mark Murphy. The women, who got instructions from someone via cellphone, paid the $150 tab in cash -- two $100 bills.

Geri Allen & Timeline, Live (Motéma). Allen's considerable strengths are on display in the pianist's recording with her trio and a percussive guest. She integrates dancer Maurice Chestnut's steely tapping with the time-keeping and soloing of her gifted young sidemen, drummer Kassa Overall and bassist Kenny Davis. Chestnut expands on the tradition established by Savion Glover and—long before—dancers like Baby Laurence who accommodated themselves to bebop. The crowds at the Oberlin Conservatory and Reed College concerts go wild at the exhilaration worked up by Chestnut and Overall. There is no denying the excitement of what they witnessed. It comes across even when one merely hears Chestnut in action. Near the end of Allen's "Philly Joe," the drummer and the dancer neatly encapsulate some of the licks the great drummer Philly Joe Jones inherited from his hero Sidney Catlett. It is impressive and somehow amusing to hear Chestnut dance the melody of Charlie Parker's "Ah-Leu-Cha."

and bassist Kenny Davis. Chestnut expands on the tradition established by Savion Glover and—long before—dancers like Baby Laurence who accommodated themselves to bebop. The crowds at the Oberlin Conservatory and Reed College concerts go wild at the exhilaration worked up by Chestnut and Overall. There is no denying the excitement of what they witnessed. It comes across even when one merely hears Chestnut in action. Near the end of Allen's "Philly Joe," the drummer and the dancer neatly encapsulate some of the licks the great drummer Philly Joe Jones inherited from his hero Sidney Catlett. It is impressive and somehow amusing to hear Chestnut dance the melody of Charlie Parker's "Ah-Leu-Cha."

It can be argued that the tapping, for all its bracing novelty, eventually becomes too much of a good thing. Allen's playing more than compensates. It is a reminder of her high rank among the pianists of her generation who succeeded Bill Evans, McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock. Aside from her inspirational role in the rhythmic energy of the album, with Chestnut sitting out she has supremely lyrical moments in Mal Waldron's "Soul Eyes" and an unaccompanied impressionistic treatment of Gershwin's "Embraceable You." She is firm in her own style but nonetheless manages to suggest Tyner's power in his signature composition "Four by Five."

At the summit of recorded collaborations between a tap dancer and a jazz band, this album may not supplant the 1952 sessions of Fred Astaire with Oscar Peterson, but it rewards repeated hearings. I recommend it for the substance of Allen's playing and the quality of her trio. Chestnut's tap dancing is a bonus.

The man who may well be the world's oldest performing jazz musician is approaching his 99th birthday. Befitting a man nearly the age of the music itself, he's from New  Orleans. Lionel Ferbos was born July 17, 1911. He played trumpet in the 1920s with bands led by Walter "Fats" Pichon and Sidney Desvigne and in the 1930s with Harold Dejan and the quintessential New Orleans alto saxophonist Captain John Handy. In demand for his reading ability and lead playing, Ferbos is the trumpeter in the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra, a band founded by guitarist and clarinetist Lars Edegran in 1967. He plays regularly at the Palm Court Café on Decatur Street. The Palm Court is planning a bash for him on his birthday.

Orleans. Lionel Ferbos was born July 17, 1911. He played trumpet in the 1920s with bands led by Walter "Fats" Pichon and Sidney Desvigne and in the 1930s with Harold Dejan and the quintessential New Orleans alto saxophonist Captain John Handy. In demand for his reading ability and lead playing, Ferbos is the trumpeter in the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra, a band founded by guitarist and clarinetist Lars Edegran in 1967. He plays regularly at the Palm Court Café on Decatur Street. The Palm Court is planning a bash for him on his birthday.

This video produced last year by the New Orleans Times-Picayune's John McCusker traces Ferbos's career. I am going to make every effort to adapt Ferbos's concluding advice about how to insure a long life and a long marriage.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary