Rifftides: March 2010 Archives

Dániel Szabó Trio Meets Chris Potter, Contribution (BMC). Szabó is a 34-year-old pianist and composer with impressive academic and performance credentials and awards in Hungary and the US. One of his professors at the New England Conservatory was Bob Brookmeyer, who sent a copy of Szabó's CD with a note strongly suggesting that his former student deserves close attention.

and performance credentials and awards in Hungary and the US. One of his professors at the New England Conservatory was Bob Brookmeyer, who sent a copy of Szabó's CD with a note strongly suggesting that his former student deserves close attention.

This album commands close attention.

Szabó's compositions have lines with binding energy that urges forward motion, and chord structures of challenging densities, prompting Brookmeyer to refer to it as "highly evolved music." Throughout, currents and undercurrents of Eastern European rhythms and minor harmonies inform both writing and improvisation. Szabó, bassist Mátyás Szandai and drummer Ferenc Németh previously recorded with guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel in an album I have yet to hear. It seems clear that it takes musicians of Rosenwinkel's and Potter's virtuosity and openness to ideas to navigate in Szabó's deep, sometimes stormy waters.  Conversely, it requires musicians of these three Hungarians' advanced techniques and jazz sensibilties to hold their own with Potter, a soloist of daunting power, swing and imagination. His work is riveting on tenor and soprano saxophones, and bass clarinet in the nostalgic piece called "Melodic." Szabós piano playing, founded in post-Bill Evans harmony and dynamics, is of a piece with the advanced concepts of his writing. His exchanges and counterpoint with Potter are natural, unforced.

Conversely, it requires musicians of these three Hungarians' advanced techniques and jazz sensibilties to hold their own with Potter, a soloist of daunting power, swing and imagination. His work is riveting on tenor and soprano saxophones, and bass clarinet in the nostalgic piece called "Melodic." Szabós piano playing, founded in post-Bill Evans harmony and dynamics, is of a piece with the advanced concepts of his writing. His exchanges and counterpoint with Potter are natural, unforced.

This album was recorded in Budapest. Potter's domestic ties to Hungary seem to take him there frequently. If that means we may expect further collaboration between him and the Szabó trio, so much the better. This is, indeed, highly evolved--and highly satisfying--music. Here are Szabó, Szandai, Németh and Potter at their CD release party in an extended version of "Attack of the Intervals," the first piece on the album.

Herb Ellis died last night at home in Los Angeles. He was 88 years old and had Alzheimer's disease. Ellis was most celebrated for his guitar playing with the Oscar Peterson Trio that also included bassist Ray Brown. For more than half a century, he was one of a handful of guitarists recognized as masters of the instrument. Musicians of several generations cherished him as a colleague. A few of them were fellow guitarists Barney Kessel, Joe Pass, Charlie Byrd and Laurindo Almeida; trumpeters Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge and Harry "Sweets" Edison; saxophonists Ben Webster, Plas Johnson and Stan Getz; and Ella Fitzgerald.

was one of a handful of guitarists recognized as masters of the instrument. Musicians of several generations cherished him as a colleague. A few of them were fellow guitarists Barney Kessel, Joe Pass, Charlie Byrd and Laurindo Almeida; trumpeters Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge and Harry "Sweets" Edison; saxophonists Ben Webster, Plas Johnson and Stan Getz; and Ella Fitzgerald.

In the notes for one of Ellis's last recordings as a leader, I wrote:

In the 24 bars of his unaccompanied introduction to "Things Ain't What They Used to Be," Herb Ellis sketches the elements of his musicality.

• Harmonic sophistication

• Fleet execution

• Expression of abstract ideas in earthy language

• Bred-in-the-bone familiarity with the blues

• Distinctive Southwest twang

• Humor

• Perfect time

When Peterson modeled his trio on Nat Cole's in 1950, he at first had Brown on bass and Cole's former guitarist irving Ashby. Then Barney Kessel signed on for a year. Ellis replaced Kessel and spent five years with Peterson. The trio became one of the most celebrated groups in jazz. Their concert recordings contain some of the most exciting music ever captured on record. Peterson, Ellis and Brown agreed that the album from the Stratford, Ontario, Shakespeare Festival in 1956 caught them at their peak. They may not have again quite reached that apogee during their time together, but they came close in this 1958 performance at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. Ellis simulates bongos, solos with all of the facets listed above, and demonstrates his skill as a rhythm guitarist.

As far as Peterson was concerned, Ellis was irreplaceable. When Herb left the trio in 1958, Peterson did not consider hiring another guitatist. He brought in drummer Ed Thigpen. That was a great trio, too, but the electricity and empathy of Peterson, Ellis and Brown was unique.

You will find a trove of Ellis albums here.

Herb Ellis, RIP.

Skipping along through 65 years of the history of a superior popular song gives us an idea of its evolution as a subject for jazz improvisation. Indeed, our examples provide an  idea how jazz improvisation itself has evolved. The song is Johnny Burke's (words) and Jimmy Van Heusen's (music) "Aren't You Glad You're You?" As Father O'Malley, Bing Crosby introduced it in the 1945 film The Bells of St. Mary's. He had a substantial hit record of it the same year. Among the singers who did covers (did they call them covers in those days?) were Frank Sinatra, Doris Day and Julius LaRosa. Later, Bob McGrath and Big Bird sang it...often... on Sesame Street. Their version is afield from our discussion, but if you're interested, you can hear it by clicking here.

idea how jazz improvisation itself has evolved. The song is Johnny Burke's (words) and Jimmy Van Heusen's (music) "Aren't You Glad You're You?" As Father O'Malley, Bing Crosby introduced it in the 1945 film The Bells of St. Mary's. He had a substantial hit record of it the same year. Among the singers who did covers (did they call them covers in those days?) were Frank Sinatra, Doris Day and Julius LaRosa. Later, Bob McGrath and Big Bird sang it...often... on Sesame Street. Their version is afield from our discussion, but if you're interested, you can hear it by clicking here.

"Aren't You Glad You're You" is a perfect marriage of optimism and sunshine in the lyrics, melody and harmony. It has a couple of chord changes that are unexpected enough to spice it up for blowing, and it's fun to sing or play. Crosby's recording seems to be unavailable on the web. LaRosa's record enjoyed a good deal of air play in the early 1950s and works nicely for our purpose. He takes mild liberties with the lyrics, employs interesting phrasing and radiates the song's happy outlook.

There may have been jazz versions of "Aren't You Glad You're You" before 1952, but the first one I know of was on Gerry Mulligan's initial quartet album for Pacific Jazz. Mulligan had gone from insider favorite to general popularity with his pianoless quartet co-starring Chet Baker. In the early 1950s it was not illegal for jazz to have general popularity. Mulligan, baritone saxophone; Baker, trumpet; Chico Hamilton, drums; Carson Smith, bass. YouTube, for reasons best known to its contributor, gives Chet the credit and the cover shot.

Cut in a sequence of pages flying off a calendar and, whaddaya know, it's November,

2009, and the John McNeil-Bill McHenry Quartet is on the stand at the Cornelia Street Café in New York. Joe Martin is the bassist, Jochem Rueckert the drummer. It may seem that after the melody chorus, our intrepid modernists leave Mr. Burke's chord scheme behind but, as I keep telling you, listen to the bass player. If McNeil seems amused by McHenry's initial solo flurry, it's for good reason.

2009, and the John McNeil-Bill McHenry Quartet is on the stand at the Cornelia Street Café in New York. Joe Martin is the bassist, Jochem Rueckert the drummer. It may seem that after the melody chorus, our intrepid modernists leave Mr. Burke's chord scheme behind but, as I keep telling you, listen to the bass player. If McNeil seems amused by McHenry's initial solo flurry, it's for good reason.McNeil and McHenry did not include "Aren't You Glad You're You?" in Rediscovery, their CD excursion into the bebop and west coast past. Perhaps it will show up on the sequel. Perhaps there will be a sequel.

Have a good weekend. Aren't you glad you're you?

Even before the recession, the business side of jazz was struggling. During the worst of the downturn, singer and nonprofit entrepreneur Ruth Price took a double hit when her Jazz Bakery lost its lease. The club is still looking for a home. Reporter Greg Burk tells the story in today's Los Angeles Times.

The Jazz Bakery is a nonprofit organization. To followers of the scene, that statement is a redundancy, of course. In Los Angeles, saying a jazz club doesn't make money is like saying a restaurant doesn't serve scrap iron.

In 18 years as president and artistic director of the Jazz Bakery, Ruth Price has alwaysknown that fresh music doesn't translate into hefty profits. Lately, though, Price has found it harder to offer quality at a discount. Last May, the Jazz Bakery lost its space in Culver City's old Helms Bakery complex when its philanthropic landlord, Wally Marx Jr., died. Since then, Price and the Jazz Bakery's 13 directors have scoured the city for a new permanent location. They report some excellent prospects but can confirm only that the club will remain on the Westside and that its status as a quiet concert venue will continue.

To read the whole story, go here.

Of the many albums recorded at the Bakery, I have long been partial to the two CDs alto saxophonist Lee Konitz and pianist Alan Broadbent recorded in concert there in 2000. The spirit of Lennie Tristano - salty and benevolent -- hovered over the bandstand that night.

Of the many albums recorded at the Bakery, I have long been partial to the two CDs alto saxophonist Lee Konitz and pianist Alan Broadbent recorded in concert there in 2000. The spirit of Lennie Tristano - salty and benevolent -- hovered over the bandstand that night.

As for Ruth Price in her artistic rather than her managerial role, she is an undersung vocalist. I mean that in two senses; she doesn't sing often enough and she doesn't get the recognition she deserves. One night at the Jazz Bakery, she was a guest for one  number during a Gene Lees evening. She sang Bill Evans' "My Bells," featuring Lees' lyrics to that beautiful Evans melody line with its devilish intervals. Ms. Price nailed it so definitively that I've been hoping ever since that she would record it. She did record at another Los Angeles club. Her CD with Shelly Manne and His Men is one of the best vocal albums of our time.

number during a Gene Lees evening. She sang Bill Evans' "My Bells," featuring Lees' lyrics to that beautiful Evans melody line with its devilish intervals. Ms. Price nailed it so definitively that I've been hoping ever since that she would record it. She did record at another Los Angeles club. Her CD with Shelly Manne and His Men is one of the best vocal albums of our time.

The technical quality is substandard in the following segment from a 1958 Stars Of Jazz program, and Bobby Troup's interview with Ruth doesn't quite get off the ground, a risk of live television. But the singing soars. Stan Levey is the drummer, and although the glimpses of them are brief, I am reasonably sure that the bassist and pianist are Scott LaFaro and Victor Feldman.

"Third Stream" seems a quaint term nearly half a century after it kicked up a bit of a fuss in jazz and classical circles. Still, it never quite goes away, as the recent Eric Dolphy posting reminded me. Two of the names that remain associated with the movement are Gunther Schuller and Leonard Bernstein. Several years ago, I wrote about Schuller's central role in creation of the term and implementation of the concept. It was in a review of a CD reissue of two daring and indelible Columbia albums of the late 1950s, Music for Brass and Modern Jazz Concert. In a moment, documentation of Bernstein's peripheral but highly visible role in the Third Stream movement. First, about Schuller from that 1997 Jazz Times review:

In his notes for Modern Jazz Concert, Gunther Schuller emphasized the unimportance of pigeonholing the music, "...I will therefore not categorize and typecast the six works on this record."Nonetheless, Schuller could not long deny the insatiable human need to label. In 1957 he created a name for this music that drew upon the jazz and classical traditions. It was "Third Stream." There had been successful meldings of the improvisation and swing of jazz with big classical forms at least as far back as Red Norvo's 1933 "Dance of the Octopus," but "Third Stream" caught on as a moniker and persuaded many listeners

that the marriage was new. If it attracted attention to the works in this album, then no harm and considerable good was done. The inspired playing of Miles Davis on John Lewis' "Three Little Feelings" and J.J. Johnson's "Poem for Brass" allowed producer George Avakian to convince Columbia to commit large resources to a Davis project that turned out to be Miles Ahead. That revived Davis' partnership with Gil Evans and led to Porgy and Bess and Sketches of Spain. "Poem for Brass" was the first major indication that J.J. Johnson was a large-scale composer. "Pharaoh" allowed Jimmy Giuffre to extend his range beyond the 16-piece band. Schuller's "Symphony for Brass and Percussion" was not a jazz composition but its presence on the Music for Brass album under the baton of Dmitri Mitropolous shed prestige on the entire undertaking.

Fast forward to 1962 and Leonard Bernstein's series of televised New York Philharmonic concerts for young people. He included in one of the concerts a piece by Schuller called "Journey Into Jazz." The segment found Bernstein entertaining, informative and wordy. The portion of the video available to Rifftides excludes much of Bernstein's setup explanation, which began with a small jazz group on stage with him. It is not just any jazz group. It is Don Ellis, Eric Dolphy, Benny Golson, Richard Davis and Joe Cocuzzo. The band plays briefly, then Bernstein says the following, leading us into the video.

BERNSTEIN: Now that's about the last sound in the world you'd expect to hear in Philharmonic Hall, isn't it? Sounds more like your next-door neighbor's radio, or the Newport Jazz Festival. And yet, that's a sound that's been coming more and more often into our American concert halls, ever since American composers began trying, about forty years ago, to get some of the excitement and natural American feeling of jazz into their symphonic music.Even so, in spite of these tries at combining jazz and symphonic writing, the two musics have somehow remained separate, like two streams that flow along side by side without ever touching or mixing--except every once in a while. But it's those once-in-a-whiles that we're interested in today: those pieces in which the jazz stream now and then does sneak over to the symphonic stream, and for a moment or two, flows along with it in happy harmony. And these days--at least, for the last five or fifty years, that is--there is a new movement in American music actually called "the third stream" which mixes the rivers of jazz with the other rivers that flow down from the high-brow far out mountain peaks of twelve-tone, or atonal music.

Now the leading navigator of this third stream--in fact the man who made up the phrase

"third stream"--is a young man named Gunther Schuller. He is one of those total musicians, like Paul Hindemith whom we discussed on our last program, only he's American. Mr. Schuller writes music--all kinds of music--conducts it, lectures on it, and plays it. Certainly he owes some of his great talent to his father, a wonderful musician who happens to play in our orchestra. We are very proud of Arthur Schuller.

But young Gunther Schuller--still in his thirties--is now the center of a whole group of young composers who look to him as their leader, and champion.

And so I thought that the perfect way to begin today's program about jazz in the concert hall would be to play a piece by Gunther Schuller--especially this one particular piece which is an introduction to jazz for young people--

The Rifftides staff thanks pianist-composer Jack Reilly and blogger Ralph Miriello of Notes On Jazz for calling our attention to the video from Leonard Bernstein's Young Peoples Concerts.

From Toronto, guitarist and author Andrew Scott sends news of a memorial event in honor of the influential Canadian jazz publisher and record company owner John Norris, who died in late January.

Sandi Norris, Ted O'Reilly, Jim Galloway, Don Thompson and I are organizing a Jazz Party in celebration of the wonderful life of John Welman Norris on Sunday April 18th from 3:00 until 8:00 at the Hart House Music Room (at the University of Toronto). A light lunch will be provided.

In addition to the music, Ted O'Reilly will be the master of ceremonies for the party. A microphone will be available for anyone who would like to share some pubic thoughts about John.

An alert Rifftides reader, Andy Rothman, sent an alert that YouTube has reinstated the Finland videos that disappeared from our Bill Evans, Relaxed And Articulate posting of May 2008. To read the reconstituted piece and view the clips, go here. Many thanks from the staff to Mr. Rothman.

There was a memorial service Sunday night in New York for the bassist Jamil Nasser, who died last month. Among those in attendance was pianist, composer and writer Jill McManus, who sent Rifftides a report.

There was a sizeable crowd at Saint Peter's Church in Manhattan on the evening of March 21st to honor and remember bassist Jamil Nasser, who died on February 13th. His strong, resounding bass playing was held in high regard. Nasser cut a wide swath through jazz from the 50s through the 70s, not only playing with top musicians, but also reaching out to produce and foster jazz. He later taught at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and was on the board of the Jazz Foundation and music director of Cobi Narita's Jazz Center of New York, which organized the event. Nasser's wife of 30 years, Barbara (Baano) Nasser was present, as were some of his five children and many family members.I remember Jamil from my early days of playing. A slim man with an impish smile, he had a big, generous sound and an immediate way of connecting with people. He was supportive, always ready to play, a good-hearted person one could talk to. I was always glad to see him. The number of musicians there last night testifies to the respect he had earned. It was a moving night -colleagues from the core of jazz history keeping alive, in a radically different time, the memory, the thread of tradition, and love.

Jamil (born George Joyner, in 1932 in Memphis) was mentored by Lester Young and Phineas Newborn, played with Newborn's trio, recorded with Red Garland, John Coltrane and Al Haig, led his own quartet through Europe in the late 50s, played in the Ahmad Jamal Trio from 1964 to 1972, and worked with such other great players as pianist Randy Weston and saxophonist George Coleman, who both performed at the tribute.

Nasser's old friend from Memphis, Harold Mabern, led off, with Jamil's son Muneer on trumpet and Lisle Atkinson on bass. With his crisp and highly rhythmic piano, Harold was dazzling. Pianist Frank Owens's authoritative stride and swing included a spot with drummer Frank Gant, a member of the outstanding Jamal trio, now somewhat handicapped, playing "Amazing Grace" on a tiny set of bells. Saxophonist Jimmy Heath, with pianist Barry Harris, Atkinson and drummer Carl Allen did a mellow "There Will Never Be Another You." Jamaican pianist Monty Alexander's island tinge blossomed on a haunting bossa written by Nasser, "Tropical Breeze." His next offering, "No Woman No Cry," was deep and solacing. Pianist Randy Weston was, for me, the high point of the evening, playing his personal blend of jazz harmonies and deep-rooted tribal sounds and rhythms, with the amazing "low-down" bassist Alex Blake, who strummed and seared, and trombonist Benny Powell, who added thoughtful melodic lines.

Bassist and deep-voiced singer Carlene Ray's extraordinary vocal rendition of "Everything Must Change" sent pure tones to the rafters and brought a chill. Pianist Norman Simmons's provocative "If I Should Lose You," assisted by Lisle Atkinson, preceded alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson's soulful version of "Body and Soul," with pianist Richard Wyands, bassist Michael Max Fleming and drummer Jackie Williams. (During Donaldson's performance, we noticed through the church window above, a homeless man flapping the sections of his cardboard box as he settled his body on the ledge for the night--and we felt blessed.) Tenor saxophonist George Coleman, also originally from Memphis, brought reminders of his many gigs over the years with Jamil. He played "I'll Be Seeing You," sometimes intertwining ideas with tenorman Ned Otter. Coleman's son, George, Jr., accompanied them on drums, with Mike LeDonne on piano and Lisle Atkinson on bass. Frank Wess did a gorgeous flute version of "The Summer Knows" with Fleming and drummer Ray Mosca, and then took a medium romp on "I Remember You." Bert Eckoff played a brief flowing piano solo and a duo with Atkinson. Jimmy Owens followed with a solo trumpet blues. Then, Monty Alexander led a brief jam that included drummer Wade Barnes and flutist Dottie Taylor.

Jamil's son Muneer Nasser has compiled a book of Jamil's interviews and life experiences called "Stories of Jazz as told by Jamil Nasser," due out in the fall. The first 100 copies include a CD with rare interview clips. It is available at Amlayna Productions.

--Jill McManus

Ms. McManus's Symbols of Hopi (Concord, 1984) features her

compositions, arrangements and piano, saxophonist David Liebman, trumpeter Tom Harrell, bassist Marc Johnson, drummer Billy Hart and American Indian percussionists. It is one of the important recordings of the 1980s still not reissued on CD. Copies of the vinyl LP occasionally show up on e-Bay and other auction sites. This one, for example.

compositions, arrangements and piano, saxophonist David Liebman, trumpeter Tom Harrell, bassist Marc Johnson, drummer Billy Hart and American Indian percussionists. It is one of the important recordings of the 1980s still not reissued on CD. Copies of the vinyl LP occasionally show up on e-Bay and other auction sites. This one, for example.

In a rare instance of Jamil Nasser on video, the clip below shows him performing with alto saxophonist Eric Dolphy in Berlin in 196l. Benny Bailey is the trumpeter, Pepsy Auer the pianist and Buster Smith the drummer. The piece is Dolphy's "245" from his 1960 Prestige album Outward Bound.

Rebecca Kilgore is a singer specializing, although not exclusively, in classic songs of the middle decades of the twentieth century. She loves Irving Berlin, Frank Loesser, Burke & Van Heusen, Dorothy Fields, Cole Porter, Dennis & Adair, Johnny Mercer, Duke  Ellington, Fats Waller. Dick Titterington, Kilgore's husband, is a trumpeter who leads a post-bop quintet. Much of his repertoire comes from Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham, Tom Harrell, Joe Henderson, Harold Land, Thelonious Monk and from the members of his band, PDXV.

Ellington, Fats Waller. Dick Titterington, Kilgore's husband, is a trumpeter who leads a post-bop quintet. Much of his repertoire comes from Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham, Tom Harrell, Joe Henderson, Harold Land, Thelonious Monk and from the members of his band, PDXV.

Kilgore is a star on cruises and the circuit of little festivals known as jazz parties whose audiences tend toward white hair and tastes formed, in spirit if not in fact, in the 1940s or earlier. PDXV plays in clubs and concerts for listeners inspired by music that developed after changes wrought in jazz by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Bud Powell. Except in their happy marriage, Kilgore and Titterington rarely comprise a team. Chatting with the audience at The Seasons last weekend, Kilgore explained their separate paths: "We have divergent tastes."

Maybe their tastes are not quite as divergent as they appear. If their concert, part of a mini-tour of the Pacific Northwest, was a reliable indicator, they might be well advised to reconsider their professional separation. In a program cleverly constructed for balance and contrast, each of the halves opened with a handful of Kilgore vocals backed by and integrated with the quintet. Short solos and occasional obbligatos by band members augmented the vocals. PDXV followed with hard-charging numbers opened up for solos from Titterington, saxophonist Rob Davis, bassist Dave Captein (all pictured), pianist Greg Goebel and drummer Todd Strait. Then Kilgore returned for a song or two to end the set. The variety and contrast seemed to settle, rather than bother or puzzle, listeners devoted to what might seem disparate genres, old pop and hard bop.

integrated with the quintet. Short solos and occasional obbligatos by band members augmented the vocals. PDXV followed with hard-charging numbers opened up for solos from Titterington, saxophonist Rob Davis, bassist Dave Captein (all pictured), pianist Greg Goebel and drummer Todd Strait. Then Kilgore returned for a song or two to end the set. The variety and contrast seemed to settle, rather than bother or puzzle, listeners devoted to what might seem disparate genres, old pop and hard bop.

Kilgore did not confine herself to The Great American Song Book. True, she gave a delightful "I Hear Music," conspired with Davis in a dramatic voice/tenor sax unison recreation of a Stan Getz solo on "Foolin' Myself," and sang a definitive version of "If I Only Had a Heart," Harold Arlen's poignant alter-ego to "If I Only Had a Brain." A seeker of half-forgotten songs, she reached into the 1950s for Bob Haymes' "You For Me." But she also sang young pop star Nellie McKay's unorthodox "The Dog Song," a gutsy cover of Curtis Stigers' "Feels Right," and went Brazilian with Susannah McCorkle's "Dilema" and João Donato's "Take Me to Aruanda." Titterington approximated Bob Brookmeyer's valve trombone asides on the Astrud Gilberto recording of "Aruanda," then spun a trumpet solo that sparkled like sun on the waters of the beach in the song. Kilgore's divergence theory took a hit when she ended her first portion of the second set with Dave Frishberg's tender "Listen Here" and PDXV followed with Hank Mobley's swaggering "Up, Over and Out." The transition made for integration, not a culture clash.

In the course of writing this piece, I discovered that Kilgore has recorded a bossa nova album that has "Take Me to Aruanda." The band on it includes Captein, guitarist John Stowell and the legendary (term used advisedly) Lyle Ritz on ukulele (yes, ukulele). I'm going to have to find that one. As for PDXV, they were in top form at The Seasons. For more about the band, see this Rifftides posting.

On his excellent blog, Jazz Profiles, Steve Cerra's new subject is Dave Brubeck. He is taking for his text the extensive booklet notes I wrote for the four-CD Brubeck box called Time Signatures: A Career Retrospective. When it popped up today, I read the essay  for the first time in years. To adapt what Paul Desmond used to say about recording, I didn't have to cough too often during the playback. To read the first of three parts and see the photographs Mr. Cerra integrated into the text, go here. Parts two and three will follow this week.

for the first time in years. To adapt what Paul Desmond used to say about recording, I didn't have to cough too often during the playback. To read the first of three parts and see the photographs Mr. Cerra integrated into the text, go here. Parts two and three will follow this week.

Thanks to Steve for the rerun.

New videos have materialized from a concert Brubeck's quartet played in Baden-Baden, Germany, in 2004, when he was a mere 83 years old. Bobby Militello was the flutist, Michael Moore the bassist, Randy Jones the drummer. The first piece is "Pennies From Heaven." Dave introduces the second one.

Have a good weekend.

Now and then the Rifftides staff rummages through the archives, wondering what was on the blog early in its history. Yesterday we found a review from four years ago, to the day. It discusses an album by a musician whose death in January, 2009 gives the last line poignancy we could not have anticipated when the piece first appeared.

FatheadOne minute and twenty-six seconds into a blues called "Bu Bop Bass" on his new CD, Cityscape, the tenor saxophonist David "Fathead" Newman begins his solo with a phrase that

consists of two quarter-note Fs, a quarter-note A and a half-note A--an interval of a major third in the key of F concert. How simple; except that it is not simple. It is complex, because Newman gives each note a customized time value that no annotator could capture on paper. They are Fathead Newman quarter notes and a half note. In addition, he gives the half note a slight downward turn, not so far that it becomes A-flat, just far enough that it's a David Newman moan, a characteristic of his expression. Furthermore, he plays the phrase, as he does all of his music, with a tone that manages to be full and airy at the same time, not quite like anyone else's tone. Newman has invested a one-bar phrase with his personality, so that anyone familiar with his work will know in that instant who is playing.

This sort of thing is what experienced musicians, fans and critics have in mind when they say that there was a time when they could recognize a soloist after a few notes. Except in the nostaligic minds of older listeners, that time is not gone, although it must be conceded that there are plenty of young soundalike players on every instrument. Is that a new phenomenon? Aside from specialists, could anyone really tell apart all of those disciples of Coleman Hawkins in the late 1930s and early forties, the herd of alto saxophonists in the 1950s who wanted to be Charlie Parker, the 1960s trumpeters who aspired to be clones of Freddie Hubbard? Imitators are eventually lost in the crowd. Individualists stand out.

On Cityscape, Newman places himself in the context of a seven-piece band similar to the six-piece Ray Charles outfit in which he became well known in the 1950s. He hasn't recorded in that

setting in a few years, and it's good to hear again. The sound and feeling are reminiscent of the Charles days, but Newman and pianist-arranger David Leonhardt have collaborated to make the harmonic atmosphere fresh. Howard Johnson fills the crucial baritone saxophone chair. Benny Powell, often sidelined by illness the past few years, is on trombone. He and Johnson solo infrequently but well. With Winston Byrd on flugelhorn, they fill out the rich ensembles behind Newman's tenor and alto saxophones. On alto in a piece called "Here Comes Sonny Man," Newman recalls "Hard Times," one of the records that made him famous with Charles.

This is basic music mining a rich tradition that grows out of jazz, rhythm and blues and the expansive territory band history of the American Southwest. No one alive does this sort of thing better than Fathead Newman.

(Originally posted on March 17, 2006.)

Governor Deval Patrick of Massachusetts grew up apart from his father, Pat. His dad was a saxophonist who devoted most of his adult life to the music and spacebound teachings of Sun Ra, the band leader who for many devotees of the avant garde epitomizes freedom and adventure in late 20th century jazz. Patrick's wild baritone saxophone solos, often played far above the horn's normal range, were for

Governor Deval Patrick of Massachusetts grew up apart from his father, Pat. His dad was a saxophonist who devoted most of his adult life to the music and spacebound teachings of Sun Ra, the band leader who for many devotees of the avant garde epitomizes freedom and adventure in late 20th century jazz. Patrick's wild baritone saxophone solos, often played far above the horn's normal range, were for more than 30 years rousing components of Sun Ra's concerts and recordings.

more than 30 years rousing components of Sun Ra's concerts and recordings.

Governor Patrick has seldom spoken about his father, but nearly twenty years after his death, the governor and his family have donated Pat Patrick's collection of scores, photographs and recordings to Berklee College of Music. In today's Boston Globe, David Abel reports on the donation, the contrast between the free-spirited father and his studious son, and their spotty relationship. The online version of the story includes a video clip with the voices of father and son and samples of Pat Patrick's playing with Sun Ra. To read it, go here.

This clip of the Sun Ra Arkestra in Berlin in 1986 will give you an idea of the difference between Pat Patrick's working environment and that of his son in the statehouse. Patrick, Sr.'s baritone sets the riff :40 into the video. Don't miss his duet with the trombonist beginning at 4:00. Take a deep breath and click on the Play symbol.

For quieter moment's in Patrick's career, you will find him in the reed section on Jimmy Heath's Really Big CD, Blue Mitchell's rare A Sure Thing and John Coltrane's Africa Brass Sessions.

Happy St. Patrick's Day.

For 15 years before he moved to the US from his native Brazil in 1993, Jovino Santos Neto was the pianist and arranger for Hermeto Pascoal, whom Miles Davis is said to have called, "the most impressive musician in the world." Santos Neto lives and teaches in Seattle and travels to Brazil frequently, keeping up with developments in music there and maintaining his tie to Pascoal. His most recent trip was to join his mentor at a music camp in Ubatuba, on the coast between São Paolo and Rio de Janeiro. They were on the faculty teaching 25 or so professional musicians and advanced students, most of them from the United States. The participants pay as much as $2,000 tuition to improve their Brazilian music skills in lush surroundings.

There are more photos from Ubatuba on Santos Neto's Facebook page.

Before his Brazilian trip, Santos Neto gave the world premiere of a new composition for piano and two flutes. His fellow performers at Symphony Space in New York were Tara Helen O'Connor (the taller of the two flutists) and Alice Jones. The piece is Agradecendo (Being Thankful).

To read a brief Rifftides review of Santos Neto's most recent CD, go here.

PDXV, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (Heavywood).

Five years ago, Trumpeter Dick Titterington brought together for one engagement saxophonist Rob Davis, pianist Greg Goebel, bassist Dave Captein and drummer Todd Strait. They discovered that their combination worked and decided to keep it going. For their name, the quintet added the Roman numeral V to the FAA acronym for the airport in Portland, Oregon, their home base. PDXV quickly developed cohesiveness, stylistic range and an identifiable sound that make them more than just another hard bop quintet. They center their repertoire in pieces by mainstream icons  including Thelonious Monk, Joe Henderson, Harold Land and Kenny Dorham. In these two albums they leaven their post-bop traditionalism with tunes from modernists Gary Dial, Steve Swallow, Tom Harrell, Dick Oatts, Fred Hersch, Stanley Clarke and the French trumpeter Nicolas Folmer.

including Thelonious Monk, Joe Henderson, Harold Land and Kenny Dorham. In these two albums they leaven their post-bop traditionalism with tunes from modernists Gary Dial, Steve Swallow, Tom Harrell, Dick Oatts, Fred Hersch, Stanley Clarke and the French trumpeter Nicolas Folmer.

All of the members are strong soloists, as they demonstrate from the outset. Vol. 1, a concert recording, opens with Land's 1972 composition "Step Right Up to the Bottom," a kaleidoscope of chord changes, time shifts and variations in dynamics that launch Davis into a gutsy, compact tenor solo. He establishes an improvisational line of inquiry picked up by Titterington and continued in solos by Goebel, Captein and Strait. It is a good introduction to the group and a demonstration of the like-mindedness that gives PDXV its solidarity. Their flawless execution of Land's challenging material at a metronome pace of 200 leaves no doubt about the players' chops. Virtuosity is an important part of the package, but dazzle does not seem to be their goal. Titterington's and Goebel's lyricism is notable in "Red Giant" by Oatts, as is Davis's on soprano in Swallow's quirky "Outfits."

The blend of the horns comes as close as anything I've heard lately to the benchmark of unity established decades ago by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Their merger is remarkable in Vol. 2 with Davis on tenor for a romp through Monk's "Trinkle Tinkle" and even more striking when he is playing soprano in unison with Titterington on Folmer's entrancing "I Comme Icare." In the Monk tune, Goebel manages an amusing tip of the turban to Thelonious without resorting to imitation or parody. For this club date, Strait sent in a sub, Randy Rollofson, not a soloist of Strait's incisiveness or melodic bent but a fine time keeper with a penchant for strategically placed cymbal splashes behind the soloists. Captein, known to many for his recordings with the Jessica Williams Trio, combines compelling work in the rhythm section with post-Scott LaFaro facility and imagination as a soloist.

remarkable in Vol. 2 with Davis on tenor for a romp through Monk's "Trinkle Tinkle" and even more striking when he is playing soprano in unison with Titterington on Folmer's entrancing "I Comme Icare." In the Monk tune, Goebel manages an amusing tip of the turban to Thelonious without resorting to imitation or parody. For this club date, Strait sent in a sub, Randy Rollofson, not a soloist of Strait's incisiveness or melodic bent but a fine time keeper with a penchant for strategically placed cymbal splashes behind the soloists. Captein, known to many for his recordings with the Jessica Williams Trio, combines compelling work in the rhythm section with post-Scott LaFaro facility and imagination as a soloist.

You Tube has several short video clips of PDXV, each featuring a member in a solo, but ony one complete performance. It is of Nicolas Folmer's "Iona." With three of his compositions on their two CDS, it is clear that the band has high regard for the young Frenchman's work. This was at the 2007 Cathedral Park Jazz Festival in Portland.

PDXV will be in concert at The Seasons in my town next weekend, with singer Rebecca Kilgore making it a sextet for part of the evening. It's an intriguing combination; a vocalist admired for the purity of her interpretations of standard songs, and a hard-charging band of rebop adventurers. I'll let you know how it goes.

Following the Ornette Coleman birthday posting three items down, Alan Broadbent sent the following:

Now, this one's absolutely true, I was there and it's never made the books.

Monk's quartet came to NZ on his "64 world tour and I and my friend Frank Gibson had good seats at Auckland's beloved Town Hall to see him. After the concert I was elected to drive Larry Gales in my '53 Ford Prefect to the Musician's Union where we held a little party for the band. Well, would you believe it, there was Thelonious all by himself standing in a corner, keeping to himself. Mostly, I think, because everyone must have been afraid to approach him. I remember him wearing a turban and occasionally doing a little twirl, which must have been somewhat intimidating to everyone, not the least me. Frank started nudging me. "Go on, Alan, go ask him something."Being a lad of 17 and discovering all kinds of new things to listen to in jazz, even in 1964 New Zealand, I had been listening to Ornette and Charlie, trying to comprehend the new "free form" jazz. I had read the term in Down Beat, I believe.

Well, I made my way through the crowd toward his little corner of the world and looked up at what seemed to me a giant of a man in more ways than one. After gingerly introducing myself, I somehow managed to tell him I was listening to Ornette and asked him if he had an opinion about this new "free form" music.

Thereupon he looked down at me and said in a low, quiet voice....

"Well.... first you said FREE..... then you said FORM."

Whereupon I thanked him and melded back into the crowd.

On this CD, Broadbent plays Monk's "'Round Midnight." I hoped to find video of him performing a Monk piece but had no luck. Instead, here he is with Charlie Haden's Quartet West in a 1999 concert in Sao Paolo, Brazil. Haden, bass; Broadbent, piano; Ernie Watts, tenor saxophone; Larance Marable, drums. Bizarrely, the YouTube clip identifies the tune as "The Long Goodbye." Maybe they'd had too many Heinekens. The piece is, in fact, Charlie Parker's "Dexterity."

Mr. Broadbent adds that rumors of Larance Marable's death are greatly exaggerated.

Larance suffered a stroke a few years back, but, although he can't speak and is infirm, his friends might like to get in touch with him at West Side Health Care where he is very much alive.

It was when I found out I could make mistakes that I knew I was on to something. - Ornette Coleman

Jazz is the only music in which the same note can be played night after night but differently each time. - Ornette Coleman

Today is Ornette Coleman's 80th birthday. In my admiration for Coleman's independence, faithfulness to his vision and inspiration, I yield to no one--except my artsjournal colleague Howard Mandel, whose lengthy Jazz Beyond Jazz tribute today is replete with Coleman history and analysis and links to recordings and books. As addenda to Howard's account of Coleman's initial breakthrough with Contemporary Records, I offer this archive item and this followup entry.

independence, faithfulness to his vision and inspiration, I yield to no one--except my artsjournal colleague Howard Mandel, whose lengthy Jazz Beyond Jazz tribute today is replete with Coleman history and analysis and links to recordings and books. As addenda to Howard's account of Coleman's initial breakthrough with Contemporary Records, I offer this archive item and this followup entry.

Over the years, there is wide variety of instrumentation and sound in Coleman's bands. For many devoted listeners, his original quartet remains the standard by which to assess the music of his other groups. Here is a clip of that band reunited in 1987 for a festival in Spain. Don Cherry is the trumpeter, Charlie Haden the bassist, Billy Higgins the drummer. Coleman's solo is a fine example of his ability to improvise little melodies that are sometimes more fetching than the tunes he writes.

When Coleman was less than a decade into his controversial career, I wrote about what stands as one of his most riveting recordings. In it, I addressed some of the issues swirling around him as the jazz community exalted and excoriated him. The piece was for Jazz Review, a radio program I did on WDSU in New Orleans in the sixties. It is included in Jazz Matters: Reflections on the Music and Some of its Makers.

1966

Ornette Coleman, Live At The Golden Circle (Blue Note)I think it's safe to assume that most people, even most jazz listeners, are not familiar with the music of Ornette Coleman. You may have heard about the controversy that has ripped through music the past six years because of Coleman's startling style and his influence on other players.

Ornette Coleman plays alto saxophone, self-taught, and he recently took a couple of years off to teach himself trumpet and violin as well. In the wake of his debut in the late fifties, there erupted a string of nonsense--played, written and spoken--which has continued and become even more absurd. One school of critics proclaimed that he had rejuvenated jazz and given it new direction. Another school said he was destroying jazz singlehandedly and that there was no hope for further good times in music. LeRoi Jones, Archie Shepp and a few dozen others in New York have decided that Coleman is a prophet of black supremacy. Coleman himself has been notably reticent on that point.

I think enough time has passed to make it clear that Ornette Coleman is neither genius nor fraud, merely a pretty fair alto player with his own vision. I was going to say, who

hears a different drummer. But, as you will hear momentarily, Coleman's drummer, Charles Moffett, is a basic, sort of old-timey drummer working in the avant-garde. And I assume that's what Coleman wants, because in many ways he himself is a basic, old-timey player. He has freed himself from some restrictions of harmony and bar lines, but I don't think he's done it because of some desperate need to escape from formal restrictions.

Coleman is a naïve, brilliant musician whose jazz sense is as instinctive as it is learned, who has the blues in his bones and who is an extremely powerful rhythmic player. He is a man in whose name some of the most outrageous and powerful cults have sprung up. Coleman doesn't deserve some of his self-appointed disciples. Nor does he deserve the burden of exaggerated praise that has proclaimed him some sort of messiah.

At any rate, here's Ornette Coleman in his first recording in three years, with Charles Moffett on drums and David Izenzon on bass. This was recorded at the Golden Circle club in Stockholm. It's call "Dee Dee."

"Dee Dee" 9:10

If you're unfamiliar with Ornette Coleman, this is a good record to begin with. If you have followed his career, it gives you an idea what he's been up to since 1962. He is interesting to hear. How much lasting musical value there is in his playing, I just don't know. I've been listening to him for five years, and I have often received tremendous emotional charges from his solos. I'll continue listening. (1966)

I have. And I will.

No, not the Sidney Bechet "Sheik of Araby" kind of one man band, but the television news kind. Today, Howard Kurtz devotes his column in The Washington Post to a phenomenon brought about in broadcast news by the convergence of technology and economic hard times.

Scott Broom turns his tripod toward the wall of gray mailboxes, adjusts the camera, walks into the shot and delivers his spiel.

"Here's how bad it is for the U.S. Postal Service," the WUSA reporter says as a handful of customers at the Garrett Park post office look on. Invoking the organization's growing deficit, which he just looked up on a laptop in his car, he puts a stamp on an envelope and declares: "At 44 cents a shot, that is a lot of peeling and sticking."Broom then thrusts the envelope toward the lens -- and blows out the iris, which has to be reset so he can try the stand-up again. It's one of the occupational hazards of being a journalistic jack of all trades -- the equivalent of singing while playing the keyboard, guitar and drums.

To read all of Kurtz's column, go here. It made me think about about standard practice in many television markets during my early years in broadcast journalism, before the digital revolution produced tiny cameras.

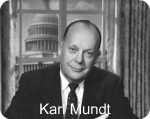

In 1963, I went to the Benson Hotel in Portland, Oregon, to interview Senator Karl Mundt of South Dakota. He was chairman of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee. American troop levels in the Viet Nam war had tripled and tripled again and I had lots of ![]() questions for him. I drove the KOIN-TV van to the hotel and schlepped the gear into the lobby only to learn that a power disturbance had fried the system that controlled the elevators. They were all out of commission. I hauled the big Pro 600 Auricon conversion 16-millimeter film camera (pictured) up six flights of stairs, knocked on the door of Mundt's suite, said I was from Channel 6 News and explained that I had to go back down for the rest of the equipment.

questions for him. I drove the KOIN-TV van to the hotel and schlepped the gear into the lobby only to learn that a power disturbance had fried the system that controlled the elevators. They were all out of commission. I hauled the big Pro 600 Auricon conversion 16-millimeter film camera (pictured) up six flights of stairs, knocked on the door of Mundt's suite, said I was from Channel 6 News and explained that I had to go back down for the rest of the equipment.

In three subsequent trips, I wrangled the enormous wooden tripod, the lights and their stands, amplifier, cables and sound apparatus up six stories. As I brought each new batch of paraphernalia into their room, Senator and Mrs. Mundt sat on the sofa sipping coffee. Small, round people with kind faces, they watched my exertions with interest and patience. I forget what Senate business took Mundt to Portland, but he did not have the entourage of staff people today's ranking politicians seem unable to do without. If he had, I would have recruited them to help carry the gear.

paraphernalia into their room, Senator and Mrs. Mundt sat on the sofa sipping coffee. Small, round people with kind faces, they watched my exertions with interest and patience. I forget what Senate business took Mundt to Portland, but he did not have the entourage of staff people today's ranking politicians seem unable to do without. If he had, I would have recruited them to help carry the gear.

As I positioned the lights, set the zoom lens for a two-shot, focused and prepared to displace Mrs. Mundt on the sofa for the interview, the senator said, "Will the reporter be here soon?"

I told him that I was the reporter and crew.

"Oh," he said. "That isn't how they do it in Washington."

It is now.

Nearly two years ago, I wrote about a Benny Carter masterpiece that received raves from musicians and critics after Count Basie recorded it for Roulette in 1960. Kansas City Suite went out of print as an LP, had a brief revival as a Capitol CD in 1990, sold poorly and has all but disappeared.

Basie's so-called "new testament" band included Thad Jones, Joe Newman, Frank Wess, Frank Foster, Marshall Royal, Benny Powell, Al Grey and the great latterday Basie rhythm section. They gave Carter's work a memorable performance. Despite clamoring by insistent bloggers (present company not excepted) for a new reissue, the Basie version is so rare as to be nearly a myth. One internet search for "Kansas City Suite" turned up an ad for hotel rooms. The recording is available only as a used LP, if you're lucky enough to find one, or an MP3 download. The Seattle Repertory Jazz Orchestra revived the suite for a concert in 2008, but live performances of the music are all too infrequent. Fortunately, one movement was captured on video while Carter was alive.

Basie's so-called "new testament" band included Thad Jones, Joe Newman, Frank Wess, Frank Foster, Marshall Royal, Benny Powell, Al Grey and the great latterday Basie rhythm section. They gave Carter's work a memorable performance. Despite clamoring by insistent bloggers (present company not excepted) for a new reissue, the Basie version is so rare as to be nearly a myth. One internet search for "Kansas City Suite" turned up an ad for hotel rooms. The recording is available only as a used LP, if you're lucky enough to find one, or an MP3 download. The Seattle Repertory Jazz Orchestra revived the suite for a concert in 2008, but live performances of the music are all too infrequent. Fortunately, one movement was captured on video while Carter was alive.

At the Berlin Jazz Fest in 1989, Carter and the WDR Big Band played the opening movement of the suite, with John Clayton conducting. Notice Clayton looking boyish and Carter, who was eighty-two, only slightly older.

The latest selection of Doug's Picks is posted in the center column, featuring a treasured vocal-piano collaboration, a new young trumpeter, an old free jazz band, a bassist at the helm of an exciting quartet, and a book that recaptures a special place at the end of New York's last golden age of jazz.

The Helen Merrill-Dick Katz Sessions (Mosaic). The bewitching singer and the late master of piano harmony and touch collaborated in 1965 and 1969 on two classic Milestone LPs. Mosaic's reissue of both on one CD is a genuine event. In addition to Merrill's incomparable singing and Katz's playing, we get Thad Jones, Jim Hall, Hubert Laws, Gary Bartz, Ron Carter, Richard Davis, Pete LaRoca and Elvin Jones. Katz's lapidary arrangements are an exquisite bonus. After hearing them for 35 years, I still smile at the surprises in his setting of "Baltimore Oriole."

The Helen Merrill-Dick Katz Sessions (Mosaic). The bewitching singer and the late master of piano harmony and touch collaborated in 1965 and 1969 on two classic Milestone LPs. Mosaic's reissue of both on one CD is a genuine event. In addition to Merrill's incomparable singing and Katz's playing, we get Thad Jones, Jim Hall, Hubert Laws, Gary Bartz, Ron Carter, Richard Davis, Pete LaRoca and Elvin Jones. Katz's lapidary arrangements are an exquisite bonus. After hearing them for 35 years, I still smile at the surprises in his setting of "Baltimore Oriole."

Ian Carey Quntet, Contextualizin' (Kabocha). Carey's self-deprecation in his liner notes would have you believe that he's not much of a trumpet player. It depends on what you mean by playing. True, there's not a double high C anywhere on the album and no jet-speed series of gee-whiz chord inversions. Let's settle for good tone, lyricism and contiguous ideas that lead somewhere. Carey and his young sidemen are in tune with one another, in every sense. In Adam Shulman he has a pianist who understands Bill Evans and in Evan Francis an alto saxophonist to keep an ear on.

Ian Carey Quntet, Contextualizin' (Kabocha). Carey's self-deprecation in his liner notes would have you believe that he's not much of a trumpet player. It depends on what you mean by playing. True, there's not a double high C anywhere on the album and no jet-speed series of gee-whiz chord inversions. Let's settle for good tone, lyricism and contiguous ideas that lead somewhere. Carey and his young sidemen are in tune with one another, in every sense. In Adam Shulman he has a pianist who understands Bill Evans and in Evan Francis an alto saxophonist to keep an ear on.

New York Art Quartet, Old Stuff (Cuneiform). As brash, iconoclastic and good-natured as the day it was born, the NYAQ comes roaring out of 1965. Trombonist Roswell Rudd, alto saxophonist John Tchicai, bassist Finn von Eyben and drummer Louis Moholo affirm that if free jazz is going to jettison formal guidelines, its players had better have musicianship, personality and the gift of listening. During its brief existence, the New York Art Quartet met all requirements. Just to prove that they were aware of where they came from, they included a glorious reading of the melody of Monk's "Pannonica."

New York Art Quartet, Old Stuff (Cuneiform). As brash, iconoclastic and good-natured as the day it was born, the NYAQ comes roaring out of 1965. Trombonist Roswell Rudd, alto saxophonist John Tchicai, bassist Finn von Eyben and drummer Louis Moholo affirm that if free jazz is going to jettison formal guidelines, its players had better have musicianship, personality and the gift of listening. During its brief existence, the New York Art Quartet met all requirements. Just to prove that they were aware of where they came from, they included a glorious reading of the melody of Monk's "Pannonica."

Martin Wind New York Quartet, Live At Jazz Baltica (Jazz Baltica). Bassist Wind returned to his native land in 2008 for Germany's Jazz Baltica Festival in Schleswig-Holstein. With the addition of the astonishing multi-instrumentalist Scott Robinson, the Bill Mays Trio with Wind and drummer Matt Wilson became the Wind quartet. The vigor, ingenuity and camaraderie among the musicians reach a peak in "Remember October 13th," with Robinson's bass clarinet alternating between the joy of unbridled freedom and the profundity of the blues. Bill Evans' "Turn Out the Stars" is another highlight. Camera work, sound and direction are beautifully realized.

Martin Wind New York Quartet, Live At Jazz Baltica (Jazz Baltica). Bassist Wind returned to his native land in 2008 for Germany's Jazz Baltica Festival in Schleswig-Holstein. With the addition of the astonishing multi-instrumentalist Scott Robinson, the Bill Mays Trio with Wind and drummer Matt Wilson became the Wind quartet. The vigor, ingenuity and camaraderie among the musicians reach a peak in "Remember October 13th," with Robinson's bass clarinet alternating between the joy of unbridled freedom and the profundity of the blues. Bill Evans' "Turn Out the Stars" is another highlight. Camera work, sound and direction are beautifully realized.

Sam Stephenson, The Jazz Loft Project (Knopf). In the late 1950s and early '60s, a loft on New York's Sixth Avenue was headquarters for master photographer W. Eugene Smith and hangout for dozens of musicians including companions as various as Zoot Sims, Pee Wee Russell, Thelonious Monk and Bud Freeman. Stephenson's narrative links transcriptions of conversations taped in the loft and pages of photographs Smith made of jam sessions and of the street life he saw from his windows. The book captures an important slice of jazz and New York history.

Sam Stephenson, The Jazz Loft Project (Knopf). In the late 1950s and early '60s, a loft on New York's Sixth Avenue was headquarters for master photographer W. Eugene Smith and hangout for dozens of musicians including companions as various as Zoot Sims, Pee Wee Russell, Thelonious Monk and Bud Freeman. Stephenson's narrative links transcriptions of conversations taped in the loft and pages of photographs Smith made of jam sessions and of the street life he saw from his windows. The book captures an important slice of jazz and New York history.

If you are a fan (sic) of the kind of language misuse eloquently exposed by the poet Taylor Mali in this recent Rifftides piece, you may enjoy the following video, a commercial for accountants.

Thanks to Bill McBirnie for calling that to our attention.

I was unable to cover the Portland Jazz Festival this year, to my regret. For reasons of economy, the festival came in compact form; one week instead of two. Jack Berry of Oregon Music News tells me he thinks that smaller was better. Berry wrote about two of the festival artists. This is some of what he had to say in advance about Pharaoh Sanders, for forty years among the freest of the free.

So this is your cup of tea or it isn't. Sanders was playing with John Coltrane on Live in Seattle and more than one acquaintance of mine considers that to be one the most astonishing experiences of their lives. Pharoah chatter on the Internet includes a rebuttal to Whitney Balliett's putdown, that it's noise, not music. Call it what you want, was the rejoinder, if it's noise it's noise of surpassing power and frequent beauty.

To read all of that piece and see video of Sanders playing in a tunnel, go here.

Berry's Sanders concert review includes this observation:

No one, prior to the Golden Age and beyond, has teased so many strange sounds out of a tenor saxophone as the Pharoah. Echo effects, warbles, ululations and splintered multi-sonics abounded. Others have gotten percussive sounds from the instrument by just fingering the pads (not blowing) but his are really loud. I kept looking at the bass player to see how he was doing that but he wasn't (at that moment) doing anything.

Here is the link to the full review.

As the Portland festival wrapped up last night, Berry heard trumpeter Dave Douglas and the band Douglas calls Brass Ecstasy, four horns and a drummer.

The association one has with brass bands is exuberance and there was that in spades. But "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" was so richly mournful that the emotional range of this instrumentation was astonishingly extended.For all of Jack's review of Douglas and company, click here.

As a young adult, Paul Breitenfeld adopted the last name Desmond. Over the years, to amuse himself and confound others, he concocted several reasons for the change. He sometimes said he did it because he thought that in the event that he ever made records, the shorter name would fit better on 78 rpm labels. In truth, the inspiration came when he and his friend and fellow saxophonist Hal Strack were at Sweets Ballroom in Oakland, California. Hal's story is in Chapter 6 of a certain book.

"We were listening to Gene Krupa's band, sometime in 1942," Strack said. "Howard Dulany had just left as the singer. The guy who replaced him had some kind of a convoluted Italian name and they decided that just wasn't going to work for a vocalist. I mean, it was more difficult than Sinatra. So, he changed his name to Johnny Desmond. We were standing there listening to the band and discussing the fact that this had happened, and Paul said, 'Jeesh, you know that's such a great name. It's so smooth and yet it's uncommon.' He said, 'If I decide I need another name, it's going to be Desmond.'"

Over the years, when asked where he got the name, he gave a variety of answers, often delivered with his enigmatic grin: from the telephone book, from the unon directory, from a newspaper, from a girl friend. He delivered these harmless put-ons with charm, conviction and the ring of sincerity. The telephone-book answer took on a life of its own and is endlessly repeated in stories about Desmond.

Now, a little family history: Because of a condition that indisposed his mother, Paul did part of his growing up in New Rochelle, New York, in the home of his father's brother Frederick Breitenfeld and his family. He became close to his cousins Rick and Ruth. Rick provided much of the research material that went into the Desmond biography. Ruth's married name is Barton. Her son Fred has extensive Broadway, motion picture and cabaret credentials as composer, song writer, orchestrator, director and actor. See his web site for full  information and MP3s of some of his work. He never met his famous second cousin, but had one memorable telephone conversation with him when Fred Barton was an 18-year-old majoring in music at Harvard. He writes:

information and MP3s of some of his work. He never met his famous second cousin, but had one memorable telephone conversation with him when Fred Barton was an 18-year-old majoring in music at Harvard. He writes:

I was visiting my Uncle Rick and Aunt Mary Ellen in December 1976 -- and I had competed to write the music for Harvard's Hasty Pudding show (my life's dream, at the time -- I wasn't thinking big!) -- anyhow, I was rejected and was beyond morose.

Rick and Mary Ellen sent a tape of the songs to Paul, and while I was visiting he called them to chat, and they suddenly put me on the phone with him. We were both a little tongue-tied, since we'd never spoken before, but we had a great chat. Paul told methat my retro-stride songs reminded me of his father.... and he assured me that I would win the competition the next year. Well, I DID win the competition the following year, and I (within the context of being typically Breitenfeldian-atheist) I had to think he was somehow winking at me "I told you so."

If only I'd been born earlier, or he'd lived longer, we'd have gotten to know each other in New York. A friend of mine plays at Elaine's Sunday nights -- I'm going to make it a hang-out.

Here is an intriguing sample of Fred Barton's writing. It's called "Psychobirds." Desmond might well have grinned at this.

I wrote "Psychobirds" at USC when I was getting my master's in Film Scoring at USC (I'm happy to announce I won the annual Harry Warren scholarship; I was old-school and retro, of course, so Warren's daughter Cookie Warren went for my stuff. She tragically died with her husband and two grandchildren in a plane crash within a month of the Award ceremony -- I still have a book of her father's songs she gave me, inscribed "YOU'D BETTER MAKE IT! -- Best, Cookie Warren" -- I'm trying, Cookie, I'm trying.....)

I was studying with David Raksin, and for one assignment, he put together a fake "main title" sequence for an imaginary movie called "Psychobirds," based on the style of the Psycho/Vertigo films, with various geometric graphics doing various dramatic things, and part of the idea was to "hit" the main events and titles -- so the piece was written tothose hits. We would routinely record with a small ensemble drawn from the USC musicians du jour. Raksin was one of the funniest and smartest people I ever met, and since I'd actually heard of (and seen) "Laura," etc. and knew all of his arcane references from the past, I was something of a teacher's pet. He started out helping Charlie Chaplin in the earliest days -- helping to turn the tune "Smile" into a film score..... (before it was a song.) One of his memorable quotes: "Madonna gives cheap vulgarity a bad name."

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary