Rifftides: November 2008 Archives

We may as well keep the Desmond string running through the weekend. After the Dave Brubeck Quartet disbanded at the end of 1967, Desmond did not play for more than a year. It wasn't a matter of simply not performing in public or not recording. He did not take his saxophone out of the case, allegedly concentrating on writing How Many Of You Are There In The Quartet? the book that never happened. He also lolled around in the Caribbean. Toward the end of 1968, he relented to the extent of recording for the A&M label's Horizon subsidiary. He was existing comfortably on his invested quartet earnings and the royalties from "Take Five," but in the early seventies something within told him that he needed the gratification of regular playing. He began appearing as a guest with Brubeck's reconstituted quartet or with Dave and his sons in the Two Generations Of Brubeck group. The Desmond interregnum period is covered in (here comes the shameless book plug) Chapter 29 of Take Five: The Public And Private Lives Of Paul Desmond.

Brubeck had taken less time to succumb again to the compulsion to play jazz. He continued to write his long-form concert works, but he assembled a band with Jack Six on bass and Alan Dawson playing drums. Gerry Mulligan, whom his friend Desmond once described as "the consummate prima donna bandleader," put aside his own leadership and a fraction of his ego to tour with Brubeck. When Desmond joined them, they often played one of his favorite Mulligan pieces, "Line For Lyons," as they did in a performance at the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1972. This clip, new to me, materialized on You Tube in the past few days.

Desmond was costumed in the glen plaid garment known as The Suit, nearly inseparable from him in his later years. We get closeups of both in another performance from the Berlin Festival. Paul is featured on a ballad he cherished, "For All We Know."

Have a good weekend.

Ted O'Reilly, the Toronto broadcaster, sent a recording of an interview he did with Paul Desmond in 1975. O'Reilly asked if there was a moment when Desmond realized the astounding degree of popularity the Dave Brubeck Quartet had achieved. Not really, Paul said, but that reminded him of a favorite question.

We were on a State Department tour in '59, and we landed in Ismir, Turkey, and there was this huge hoop-de-do at the airport. They had a band playing one of our tunes, and a whole bunch of people; jazz fans and critics and whatnot. We were schlepping all of the equipment and baggage and everything to the hotel. Press conferences and interviews and pictures and all of that went on for an hour or so. Then, ultimately, it all subsided and I was sitting in the bar. There was nobody much left except this one guy who came up and said, "How long have you been famous?"

I said, "Well! That's sort of hard to pin down. I suppose it would depend on whether you

start with the Columbia records or the concerts and Fantasy. Oh, I don't know, I guess maybe 1954 or somewhere around there."And then he said, "What's your name?"

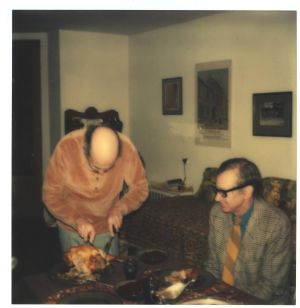

Yesterday was Paul Desmond's eighty-fourth birthday. Years after Paul's death, his guitar companion Jim Hall said, "He would have been a great old man," The last birthday Desmond celebrated, his fifty-second, fell on Thanksgiving, 1976. He spent it with Jim and his wife Jane at their daughter's tiny apartment in New York City. He had taken a hiatus from his lung cancer therapy to play the Monterey Jazz Festival and an engagement at Barnaby Conrad's El Matador in San Francisco. From Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond, this is an account of that Thanksgiving day. The photographs, never before published, are courtesy of Devra Hall.

Back in New York, Desmond resumed his chemotherapy treatments and spent time with friends. Jim and Jane Hall's daughter, Devra, had been graduated from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusets and was living on 89th Street between West End and Riverside Drive. Her mother announced to her that now that she had her own place, Devra would be hosting Thanksgiving dinner. Thanksgiving and Desmond's 52nd birthday came on the same day, November 25, 1976.

"I told her, 'Okay, but you have to bring Paul,'" Devra said. "I knew what Mom would do, so I went to the market on Broadway and got this turkey and, mind you, my kitchen was

the size of a small bathroom. To open the oven, you had to stand outside the kitchen door. This is New York, my first apartment and my first turkey, I'm growing up and very pleased with myself. I followed all the instructions, turned on the oven and put it in. We all knew Paul was sick. I think he had just finished a chemo treatment, but he said he felt up to it, and he and my folks came to this tiny one-room apartment. There was no bed, just a pullout couch; it was all folded up. Paul was sitting in the little brown canvas sling chair. There was an upright piano that my dad had bought me for my birthday, a chest of drawers and a drop leaf table at which we had dinner. That was it for furniture. Well, they're sitting there. My mother says, 'So, how's the bird? I say, 'Well, go check it out.' She opens the oven--I couldn't go in there with her; there was no room--and she closes the door and she's laughing. You know, I'm mortified. I can't imagine what's wrong.

"Paul's saying, 'What's wrong, didn't she turn on the oven?' Jim can't decide whether I'm going to cry or what. It turns out that I had put the turkey in the oven upside down. Don't the legs go on the bottom? I mean, isn't that how the bird stands? We later determined that I was ahead of my time. Today, that's the chef's secret to keeping the meat moist. It turned out fine. It was a very quiet dinner. Paul was not feeling well, but he was clearly happy not to be home alone. He didn't have to say a word around my folks. They talked a blue streak, usually, but he was just very comfortable. My fondest recollection is that I made him dinner on his last birthday."

The senior Halls and Desmond went back to Jim and Jane's apartment when they left Devra's, and on the way stopped at the Village Vanguard. Thelonious Monk was performing there. Between sets, they all gathered in the Vanguard's kitchen, the closest thing the club has to a Green Room.

"It was the most coherent conversation I ever had with Thelonious," Hall said, "in the kitchen with Paul and me and Thelonious. I had a sort of nodding acquaintance with Monk, but he and Paul really connected. I'm not even sure what they talked about, just standing around in that kitchen, going through old memories and things. It was nice."

To listen to The Sound Of A Dry Martini, producer Paul Conley's classic National Public Radio documentary about Desmond, click here.

In New York in '57, his front-line partner was Bill Harris, the eccentric and endlessly inventive trombone hero of several editions of the Woody Herman band. Among the players in the pianoless rhythm sections were bassist Oscar Pettiford, drummer Don Lamond and, in separate sessions, guitarists Kenny Burrell, Jimmy Raney and Chuck Wayne. Bob Zieff wrote arrangements for the two horns and a five-man string section that included Harry Lookofsky and other leading studio players of the day. It is puzzling that Zieff, noted for an advanced compositional style and the unusual pieces he created in the fifties for Chet Baker, gave the string writing here little of the harmonic astringency and complexity of line for which he was known. It was a missed opportunity. No matter; with superlative rhythm section support, Nimitz and Harris are unhampered, even gleeful, in their solos on "Somebody Loves Me," "Softly as in a Morning Sunrise" and seven other standards. Their hand-in-glove exchanges and intertwining on several pieces are a joy.

inventive trombone hero of several editions of the Woody Herman band. Among the players in the pianoless rhythm sections were bassist Oscar Pettiford, drummer Don Lamond and, in separate sessions, guitarists Kenny Burrell, Jimmy Raney and Chuck Wayne. Bob Zieff wrote arrangements for the two horns and a five-man string section that included Harry Lookofsky and other leading studio players of the day. It is puzzling that Zieff, noted for an advanced compositional style and the unusual pieces he created in the fifties for Chet Baker, gave the string writing here little of the harmonic astringency and complexity of line for which he was known. It was a missed opportunity. No matter; with superlative rhythm section support, Nimitz and Harris are unhampered, even gleeful, in their solos on "Somebody Loves Me," "Softly as in a Morning Sunrise" and seven other standards. Their hand-in-glove exchanges and intertwining on several pieces are a joy.

Nimitz's foil In the 2007 session is Adam Schroeder, a young baritone player based in Los Angeles, as Nimitz has been for decades. Schroeder's tonal quality is close to Nimitz's latterday sound, but his conception seems to reflect that of Pepper Adams, and the contrast makes it fairly easy to tell them apart. If anything, Nimitz has gained pzazz in his later years. He frequently reaches into the baritone's sub-basement for deep tones that challenge your woofer, and is likely to leap into tenor saxophone range for bursts of lyricism. As in the earlier session, most of the material is standard songs or originals based on them. Mike Barone's sprightly "Waltz This" is an exception.

Toward the end of "More Friends" ("Just Friends"), the two baritones indulge themselves in a chorus of unaccompanied counterpoint that is as much fun to hear as it must have been to play. There is more of it on "It's You or No One." Nimitz's stately ballad playing on "Polka Dots and Moonbeams," with a couple of Serge Chaloff references, is a highlight.The only strings on this occasion were those of the superb bassist Dave Carpenter in one of the last recordings before his death in June at the age of forty-eight. John Campbell is the pianist, Joe La Barbera the drummer, rounding out a first-rate rhythm section. This is a rare and welcome release, a recording led by Jack Nimitz in the middle of one century and the beginning of the next.

Bill Evans had precise intellectual understanding of everything he did in his playing. However, like most superior improvisers, he developed his skill and knowledge to the point where he could set aside concentration on keyboard technique and the elements of musical language in order to achieve an unfettered flow of creativity in the spontaneous act of playing jazz. On occasions when he talked about the nature of improvisation, Evans spoke with exactitude and coherence to match his expressiveness at the piano. The most widely known example of his verbal eloquence is in conversation with his brother Harry, a music educator, in a 1966 television program called The Universal Mind of Bill Evans, which is available on DVD.

Bill Evans had precise intellectual understanding of everything he did in his playing. However, like most superior improvisers, he developed his skill and knowledge to the point where he could set aside concentration on keyboard technique and the elements of musical language in order to achieve an unfettered flow of creativity in the spontaneous act of playing jazz. On occasions when he talked about the nature of improvisation, Evans spoke with exactitude and coherence to match his expressiveness at the piano. The most widely known example of his verbal eloquence is in conversation with his brother Harry, a music educator, in a 1966 television program called The Universal Mind of Bill Evans, which is available on DVD.

Now, three revealing video clips have surfaced. They were taped nearly thirty years ago at a private house concert in Finland. The Evans trio played and he talked with his hosts about his music-making. Asked how far the intellect goes in playing jazz, he replied:

Only as far as being a student. You couldn't manipulate yourself fast enough intellectually, to play. I mean jazz is a certain process that is not an intellectual process. You use your intellect to take apart the materials and learn to understand them and learn to work with them. But, actually, it takes years and years of playing to develop the facility so that you can forget all of that and just relax, and just play.

At the end of the third sequence, bassist Eddie Gomez and drummer Marty Morrell, also speak. These You Tube clips are apparently from a television program that aired in Helsinki. As far as I've been able to discover, they have never been commercially available. This was about a decade before Evans' death in 1980. Relaxed in comfortable surroundings and congenial company, he even smiles, a rarity in video recordings of Evans. The first clip has Evans speaking.

The two remaining clips have the Evans trio playing "Alfie" and "Nardis." You can view them by clicking here and here.

The Rifftides staff is still catching up with recent CDs, some more recent than others.

Sheila Jordan, Winter Sunshine (Justin Time). The first word in the CD's title may refer to

Jordan's age, the second to the quality of her singing. She is seventy-nine and sounds thirty. Part of her schtick in this live recording at Montreal's Upstairs club is to tell the audience how tired she is, but she doesn't sound tired. She sounds like a young bebop and ballad singer with sunshine in her voice. If there must be scatting, let it be the kind of canny scatting Jordan does in "I Remember You" and her montage of "All God's Chillun Got Rhythm" and "Little Willie Leaps." She praises pianist Steve Amirault, bassist Kieran Overs and drummer André White...for good reason. The chatter between songs wears thin after two or three hearings, but it is on separate tracks, and most CD players are programmable.

Jordan's age, the second to the quality of her singing. She is seventy-nine and sounds thirty. Part of her schtick in this live recording at Montreal's Upstairs club is to tell the audience how tired she is, but she doesn't sound tired. She sounds like a young bebop and ballad singer with sunshine in her voice. If there must be scatting, let it be the kind of canny scatting Jordan does in "I Remember You" and her montage of "All God's Chillun Got Rhythm" and "Little Willie Leaps." She praises pianist Steve Amirault, bassist Kieran Overs and drummer André White...for good reason. The chatter between songs wears thin after two or three hearings, but it is on separate tracks, and most CD players are programmable.

Mike Longo, Float Like a Butterfly (CAP). I hope that before Oscar Peterson died last December he had a chance to hear Longo's treatment of "Tenderly" in this 2007 CD. Longo emulates the first chorus of the master's famous 1952 recording, then pursues his own muse with forthrightness, imagination and relaxed swing. Peterson would no doubt have been pleased with his prize student on both counts. Longo's longtime confreres Paul West and Jimmy Wormworth are the bassist and drummer. The trio plays a couple of the leader's own tunes and explores several by Monk, Gillespie, Shorter, Hubbard, Raksin, Van Heusen, Schwartz and others. This is an unpretentious and deeply satisfying recording, nowhere more so than in Longo's clever blues "Diminished Returns."

Kenny Garrett, Sketches of MD: Live At The Iridium (Mack Avenue). The alto saxophonist eases off his customary Coltrane modal intensity for a club date incorporating soul, neo-Africanisms and synthesizer funk. The MD of the title refers to Garrett's stint with Miles Davis

in the trumpeter's late electronic period. The veteran tenor saxophonist Pharaoh Sanders brings to the proceedings an earthiness that rubs off on Garrett. Or is it vice versa? The rhythm section of bassist Nat Reeves, drummer Jamire Williams and keyboard player Benito Gonzalez provides the hypnotic backgrounds in this album of good-natured party music.

Barack Obama has the capacity to overcome the recent image of a global bully by restoring America's reputation as a peace-loving, progressive nation. But he faces far greater priorities during his first weeks and months in office as president than say the future of the Voice of America. An entire generation may well be perplexed by just what the VOA means. But the international buzz caused by President-elect Obama earlier in the month offers him an opportunity to revive what had been a valuable American resource for so many years. In short, the reputation of the Voice needs to be revived and treasured -- not squandered as it has been by the Bush Administration the past eight years.

It was the regularly scheduled broadcasts of Willis Conover, the music maestro who spread the love of American jazz around the world. During the worst of times in the Soviet Union I remember Russian musicians taping Conover's daily programs and then transcribing the music to sheet music for jam sessions of their own. There also were often countless days when Soviet Jews and other political dissidents who had heard VOA programming, would thank me for telling their stories to the outside world in my CBS News radio broadcasts from Moscow that were repeated by the Voice of America.

To read all of Fromson's column, go here. For two of the many previous Rifftides postings about the VOA and Conover, go here, here and here. To be repetitive in an area in which repetition is needed, allow me to suggest that if you're a US citizen, you send to your senators and congressman a letter or message something like this one, which I sent nearly two years ago:

I urge you to fight the Bush administration's budget cuts that would result in the Voice of America stopping or reducing English Language news broadcasts. At a time when the US image around the world is soiled, we need continuation of the objective shortwave news programs whose very existence has informed millions about our nation, not to mention helping them learn English so that they might better understand what The United States of America stands for. This proposed budget cut would effectively disable one of the few official cultural exchange vehicles left to us. Please discuss this with your Senate and House colleagues and do all that you can to preserve the VOA.

The influential Public Diplomacy Council, a coalition of foreign policy specialists including diplomats and academics, has joined the chorus urging the new administration and the Congress to move quickly to resuscitate the VOA. For a report, click here.

Trumpeter and flugelhornist Marvin Stamm just spent a few days at the Brubeck Institute in Stockton, California. While he was there, he worked with jazz musicians visiting the institute from Russia.

Rifftides reader Paul Conley of radio station KXJZ in Sacramento (pictured) also visited, He aired a story about the encounter on National Public Radio's Morning Edition. To listen to Conley's report, click here.

Rifftides reader Paul Conley of radio station KXJZ in Sacramento (pictured) also visited, He aired a story about the encounter on National Public Radio's Morning Edition. To listen to Conley's report, click here.

When Marc Myers at JazzWax.com decides to solve a mystery, he goes into full Sherlock Holmes mode. He has done that in an attempt to track down the complete personnel of the Shorty Rogers combo in the Looney Tunes cartoon Three Little Bops, which ran last week on Rifftides. I agree with critic Larry Kart's conclusion that the baritone saxophonist is

Jimmy Giuffre. Follow this link to see the cartoon again and read Kart's message. Giuffre worked often with Rogers in the 1950s, and the baritone in the film has the sound of Giuffre's celebrated spoof R&B hit "Big Girl" with the Lighthouse All-Stars (CD cover pictured). Myers takes an interesting route to reach another conclusion about the baritone player. His detective work produces plausible speculation about the identities of the bassist, drummer and guitarist. See Marc's posting here.

celebrated spoof R&B hit "Big Girl" with the Lighthouse All-Stars (CD cover pictured). Myers takes an interesting route to reach another conclusion about the baritone player. His detective work produces plausible speculation about the identities of the bassist, drummer and guitarist. See Marc's posting here.

What matters most is that a delightful cartoon period piece is getting renewed attention. Still, if anyone out there in cyberspace has definite information about the makeup of the band, please let us know by way of the comment link below.

David Sherr, OtherWorld Music (Bel Air Jazz). Sherr is a composer and player of reed instruments and flutes. His background includes work with Sonny Criss, the San Francisco Ballet, Nelson Riddle, Lalo Schifrin, Don Ellis, Harry "Sweets" Edison, Frank Zappa, Oliver Nelson, Robert Craft, Ray Charles and Quincy Jones, among several dozen others from assorted fields of music. In this CD, he brings together extensive portions of his music with that of J.S. Bach and Olivier Messiaen.

Sherr enlists members of the Bach Aria Group and superb jazz musicians including drummer Joe La Barbera, pianist Tom Ranier and bassist Harvey Newmark. His unaccompanied clarinet exposition of the third movement of Messiaen's Quartet For The End Of Time is brilliantly executed. He integrates free jazz with elements of Messiaen's formidable quartet and succeeds in making all but the most perceptive and experienced listeners wonder about the line between what is written and what is improvised. In his "...Then Have I The Eagle's Powers, Then Soar I Up From This World," Sherr accomplishes a similar feat with themes from Bach's "Aria" from Cantata 56. In it, voices deliver lines in several languages as if they were instruments in counterpoint, the jazz players free-associate with one another at a high level and a solo violin melds with the entrance to the next piece, Messiaen's flute-piano duet "Le Merle Noir."

Sherr enlists members of the Bach Aria Group and superb jazz musicians including drummer Joe La Barbera, pianist Tom Ranier and bassist Harvey Newmark. His unaccompanied clarinet exposition of the third movement of Messiaen's Quartet For The End Of Time is brilliantly executed. He integrates free jazz with elements of Messiaen's formidable quartet and succeeds in making all but the most perceptive and experienced listeners wonder about the line between what is written and what is improvised. In his "...Then Have I The Eagle's Powers, Then Soar I Up From This World," Sherr accomplishes a similar feat with themes from Bach's "Aria" from Cantata 56. In it, voices deliver lines in several languages as if they were instruments in counterpoint, the jazz players free-associate with one another at a high level and a solo violin melds with the entrance to the next piece, Messiaen's flute-piano duet "Le Merle Noir."

This is music full of rich satisfactions, more of which become apparent on successive hearings. If Sherr attracts the attention he should with this unconventional and intriguing project on an obscure label, we will undoutedly be hearing more from him.

In his teenage years during the waning days of the big band era, Sherr went on the road as a saxophone player. His web site contains a long, occasionally disturbing and very funny journal of that experience. Here's a sample.

Ernie Fields And His World Famous Orchestra, that's us. A big hit record, a couple of smaller hits, the Dick Clark Show, the Regal theater, the country's Number One R&B band and bookings in some pretty classy joints, like the one the other night near Dallas. And then again...

Tonight it was Temple, Texas, just south of Waco. (Wyatt has been calling it "Whacko" since this morning.) The sign over the entrance said "Rec Center" but "wreck center" would have been more like it. It had broken windows and chairs, a tiny stage and a piano that may never have been tuned. Roosevelt counted thirteen keys that didn't work. He tried to get around the missing notes and wound up sounding like Thelonious Monk.

Billy's bass drum kept slipping. He took a hammer he kept for such emergencies and drove a couple of nails into the rotting floor of the stage to brace the drum. The guy in charge of the building screamed, "What are you doing to my stage," and ordered him to remove the nails. Bill pointed out that the "damage" was already done, so why not leave them in until we were finished, but the guy said no. So Billy pulled the nails and spent the rest of the night trying to keep from kicking the drum off the stage.

To read all of "On The Road At 18," click here.

TWO CDs BRIEFLY NOTED

Philip Catherine, Bert Joris, Brussels Jazz Orchestra, Meeting Colours (Dreyfus). This has

been out since 2005. I loved the album when I first heard it and just rediscovered it in a stack of review copies. Guitarist Catherine and trumpeter Joris, both Belgian, are the principal soloists in this collection of Joris's arrangements of Catherine's compositions (plus Ellington's "In a Sentimental Mood") for the superb Brussels Jazz Orchestra. Joris is one of the finest trumpet soloists in the world. His writing is as good as his playing. Catherine, most widely known for his work with Chet Baker, Tom Harrell and Larry Coryell, solos with his customary imagination, economy and love for Wes Montgomery.

Drori Mondlak, Point In Time (Lilypad). Mondlak's quartet is integrated, balanced and musical, with no show-off features for the drummer leader. Mondlak, saxophonist and flutist Karolina Strassmayer, guitarist Cary DeNigris and bassist Steve LaSpina solo with conviction. Except for Frank Foster's "Simone," the pieces are by members of the quartet. The collection might have benefited from more of the grit of DeNigris's "I've Paid Some Blues" and "No Name Blues" and Mondlak's "The Prance," but if Mondlak's aim was to create an atmosphere of thoughtful relaxation, he succeeded. Mondlak has a witty solo on Strassmayer's "It Once Was a Waltz." LaSpina's fluidity and strength are important to the success of this music. Strassmayer's work shows why she is one of the most interesting alto saxophonists under forty. DeNigris's and Mondlak's like-mindedness contribute to the success of the venture.

Drori Mondlak, Point In Time (Lilypad). Mondlak's quartet is integrated, balanced and musical, with no show-off features for the drummer leader. Mondlak, saxophonist and flutist Karolina Strassmayer, guitarist Cary DeNigris and bassist Steve LaSpina solo with conviction. Except for Frank Foster's "Simone," the pieces are by members of the quartet. The collection might have benefited from more of the grit of DeNigris's "I've Paid Some Blues" and "No Name Blues" and Mondlak's "The Prance," but if Mondlak's aim was to create an atmosphere of thoughtful relaxation, he succeeded. Mondlak has a witty solo on Strassmayer's "It Once Was a Waltz." LaSpina's fluidity and strength are important to the success of this music. Strassmayer's work shows why she is one of the most interesting alto saxophonists under forty. DeNigris's and Mondlak's like-mindedness contribute to the success of the venture.

In today's Washington Post, Matt Schudel writes about Frank Wess. The 86-year-old tenor saxophonist and flutist is still active and about to play in Washington, D.C., where he spent much of his early career. Schudel quotes pianist Billy Taylor, Wess's contemporary, about the saxophonist's influence on him when they were in high school together.

"He's the reason I don't play the tenor saxophone," Taylor says. "I was going to try to be the new Ben Webster," the tenor saxophonist who worked with another notable Washington jazzman, Duke Ellington.

Then Taylor heard Wess, and he decided to stick with the piano.

"Even in his teens, he was really a remarkable player," he says.

To read all of Schudel's article, click here.

Wess was a principal arranger and soloist in Count Basie's band during the 1950s and early '60s. In this video clip, he solos on his composition "Corner Pocket," following trumpeters Thad Jones and Al Aarons.

The You Tube heading for this video clip of Toots Thielemans at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1992 says that it has been viewed 40,422 times. Do yourself a favor and make it 40,423. Quincy Jones was the conductor of the WDR Big Band. He was enamored of Toots's musicality, wit and warmth. Who isn't?

Have a good weekend.

And if I have a strong point, it's that I like to believe it's not cheap or schmaltzy sentimentality.

You can be in Tokyo or Alberta at four in the morning in your hotel and you can still practice if you feel like it. A trombone cannot do that at four in the morning.

The Rifftides staff is attempting to keep ahead of the CD tsunami described in this recent post. It's an impossible assignment, but they're a game bunch. Herewith, brief reviews of approximately 0.06% of the accumulated mass of discs.

Sonny Rollins, Road Shows, Vol. 1 (Doxy/Emarcy). In some of these previously unreleased concert performances, the tenor saxophonist reaches peaks of the intensity, drive, inventiveness and whimsy that have kept him inimitable for nearly six decades. His "Tenor Madness" solo from Japan in 2000 is one of Rollins's most compelling recorded blues statements. There's a remarkable "Easy Living" from Poland in 1980. "More Than You Know," recorded in France in 2006, concludes with a ravishing extended cadenza that is a tour through the inner workings of a great melodist's creative process. The most recent track, "Some Enchanted Evening," from Rollins's 2007 Carnegie Hall concert, is curiously tentative despite the presence of bassist Christian McBride and drummer Roy Haynes. The architectonic "Blossoms," from Sweden in 1980, is anything but tentative. Full of risk-taking, it is twelve-and-a-half minutes of Rollins at his most penetrating and complex.

Mike Melvoin and Kim Park, The Art Of Conversation (City Light). Pianist Melvoin and alto saxophonist Park, veterans who deserve wider recognition, shine in this aptly-named duo collaboration. It grew out of Park's sitting in on a Melvoin gig in Kansas City. Park makes engaging personal use of inspiration from his KC predecessor Charlie Parker, notably so in

his visceral, blues-inflected soloing on "I Remember You," a tune lastingly linked to Parker. The fleetness and harmonic richness of Melvoin's improvisations are consistent throughout this collection of familiar standard songs. As for justification of that title, he and Park truly listen to and stimulate one another's ideas, as good conversationalists will. This music is available as a download.

Billy Harper, Blueprints Of Jazz, Vol. 2 (Talking House). Harper was one of the most profound of the tenor saxophonists to emerge in the wake of John Coltrane. This CD, full of post-Coltrane muscle and mysticism, recalls the swirl of free jazz in the sixties and seventies, even unto Amiri Baraka reciting his jazz-history-lesson poetry and Harper on one track singing a little like Leon Thomas did on all those Impulse! LPs. Fronting a relentlessly energetic septet of like-minded seekers, Harper solos with his full range of formidable technical mastery and the power and conviction of a gifted preacher. This CD seems to be hard to get. Although it was released in October, Amazon is the only web site I can find that is offering it. Amazon claims to have just one copy--used--at $90.00 U.S. (!) It may be available as an MP3 download.

Billy Harper, Blueprints Of Jazz, Vol. 2 (Talking House). Harper was one of the most profound of the tenor saxophonists to emerge in the wake of John Coltrane. This CD, full of post-Coltrane muscle and mysticism, recalls the swirl of free jazz in the sixties and seventies, even unto Amiri Baraka reciting his jazz-history-lesson poetry and Harper on one track singing a little like Leon Thomas did on all those Impulse! LPs. Fronting a relentlessly energetic septet of like-minded seekers, Harper solos with his full range of formidable technical mastery and the power and conviction of a gifted preacher. This CD seems to be hard to get. Although it was released in October, Amazon is the only web site I can find that is offering it. Amazon claims to have just one copy--used--at $90.00 U.S. (!) It may be available as an MP3 download.

Jerry Gonzalez y Los Piratos Del Flamenco (Sunnyside). Since he moved to Madrid, the trumpeter, flugelhornist, conguero and co-leader of the Fort Apache Band has gone well beyond taking an interest in Spain's flamenco tradition. He has absorbed its mystique and

even begun to have an effect on its evolution. The closely held flamenco community has let him in and Gonzalez has managed to get them to accept the idea of jazz improvisation in the context of contemporary flamenco performance. In a cultural feedback loop, Gonzalez brings jazz sensibilities inspired by Miles Davis and Gil Evans into the milieu of Spanish music that helped to inspire the classic Davis-Evans album Sketches Of Spain. His venture is a work in progress. This CD demonstrates the results so far. "Monk's Dream (Monk's Soniquete)" with Gonzalez overdubbed on multiple horns to the accompaniment of flamenco hand-clapping rhythm is, as they say in Madrid, un viaje.c

Sometimes comments about Rifftides pieces show up considerably after publication. We just got one from reader Dave Mackey about an animated cartoon we linked to on April 30, 2007. Bless the readers. We wouldn't have known about the cartoon if a reader hadn't sent an alert in the first place. The paragraph immediately below is the original item. It is followed by the Looney Tunes itself, now embedded in the blog. And THAT is followed by Mr. Mackey's comment. It's a great reason to rerun a minor masterpiece.

Rifftides reader Bruce Tater came across a classic Warner Bros. cartoon from the Looney Tunes series. He called our attention to Three Little Bops, a perfectly preserved piece of 1950s hipness. Stan Freeburg is the narrator. Shorty Rogers did the music. Notice the stylized drawings of the nightclub audience. Don't miss Shorty's little sui generis muted solo near the end.

If you know the other musicians, please let us in on it by way of a commentIt's likely those nightclub denizens were drawn by assistant animator Bob Matz; most of the heavy lifting was done by Gerry Chiniquy, who was simply one of the most brilliant animators in the Friz Freleng unit and deserved this showcase.

Now, a music question: anyone know who else played on the session? The music was recorded on the Warner Bros. soundstage by the regular crew that recorded the cartoon scores. The bare music score exists and was released on one of the recent Looney Tunes DVD's, and it's slated by Milt Franklyn, who was one of the studio's two musical directors (the other being the legendary Carl Stalling).

Dave Mackey

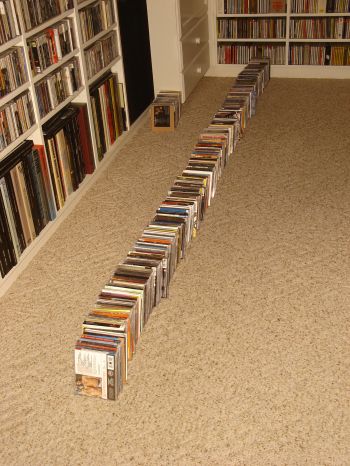

Jazz isn't dead or dying. It's just waiting to be heard. The photograph shows an eleven-foot line of CDs on the floor of my music room. There are 352 of them. They are some of the review copies that have arrived in the past couple of months. Boxes and shelves in my office hold at least three times that many more. A stack of DVDs on the credenza behind where I am writing reaches to within a few inches of the ceiling. None of these recordings is yet in the permanent collection. They are languishing, hoping to be reviewed.

I estimate that there are 1,050 CDs and thirty-five DVDs on hold. Let's assume that each is an hour long, a low average. If I were to spend eight hours a day, including weekends, listening and watching, it would be--appropriately--April 1st, 2009, before I finished. But I would not finish because long before then I would have been taken to the loony bin. In the meantime, at the current rate, a couple of thousand more recordings will have arrived. Did I mention the storage problem?

All a reviewer can do is hope that experience, knowledge, instinct and luck will guide him toward what to pull from that long line. If the next Armstrong, Young, Parker, Evans, Coleman or Coltrane is there and I miss him (or her), I'll be sorry, but listening is a linear proposition, and there's only so much time.

Below is the next installment in my attempt to keep up with the endless flow of recordings.

Kenny Wheeler, Other People (Cam Jazz). Perenially adventurous, always on the leading edge of music, Wheeler was seventy-five when this was recorded in 2005. His

playing on trumpet and flugelhorn is brilliant, with little of the lassitude that has sometimes crept in as he aged. The even more striking aspect of this CD is Wheeler's writing. He applies his distinctive style to strings, a medium new to him as a composer.

Lacing his horn lines through and around the Hugo Wolf String Quartet, Wheeler brings to string writing the tart voicings, subsurface rhythms and plaintive melodies that have long characterized his compositions and orchestrations for combinations of horns. The Wolf Quartet's interpretations of the sections with long, keening lines emphasize the pungency and poignancy that is central to Wheeler's work. On some

pieces, Wheeler's frequent piano companion John Taylor solos with his customary incisiveness and lyricism. The most stunning achievement in the recording, however, has neither horn, piano nor improvisation. It is Wheeler's "String Quartet n. 1," a through-composed concert work with riveting thematic development and gently insistent rhythmic pulses. This is the belated debut of a composer of concert chamber music to be taken seriously.

Don Thompson Quartet, For Kenny Wheeler (Sackville). Thompson is one who takes Wheeler seriously, indeed. In his CD notes about Wheeler, the composer, bassist, pianist and vibraharpist writes of his fellow Canadian:

I can't think of anyone else in jazz with his gift of melody and understanding of harmony and counterpoint. It's my opinion (and that of many others) that Kenny is the most important composer in jazz today. To me he is today's Duke Ellington.

All of the compositions are by Thompson. Only "For Kenny Wheeler" and "K.T.T." (Kenny

Type Tune) overtly refer to Wheeler in their titles. Throughout, Thompson's compositional methods reflect Wheeler's. Because of the skill and assurance of the quartet, this complex music flows as naturally as if was standards and ordinary blues. Thompson's sidemen are his longtime colleague Terry Clarke on drums (they were together in Paul Desmond's last band), saxophonist Phil Dwyer and bassist Jim Vivian, three of Canada's most distinguished musicians.

Type Tune) overtly refer to Wheeler in their titles. Throughout, Thompson's compositional methods reflect Wheeler's. Because of the skill and assurance of the quartet, this complex music flows as naturally as if was standards and ordinary blues. Thompson's sidemen are his longtime colleague Terry Clarke on drums (they were together in Paul Desmond's last band), saxophonist Phil Dwyer and bassist Jim Vivian, three of Canada's most distinguished musicians.

Thompson plays piano on six of the tracks, vibes on two with Dwyer supporting him and soloing on piano. Dwyer tends toward dreaminess on soprano and gutsiness on tenor, as in the decidedly unordinary "The Peregrine Blues," with its eccentric intervals and glancing counterpoint with Thompson's piano. Vivian and Clarke are splendid throughout. Clarke's brush and cymbal commentary behind Dwyer's tenor on "Another Time, Another Place" is a highlight, Vivian's solo on "For Scott LaFaro" another. The recordings I return to for frequent play over the years are those in which I keep hearing new facets. This seems destined to be one of those albums.

As usual, things are happening in jazz in Philadelphia, the town that produced John Coltrane,

Ray Bryant, Red Rodney, the Heath brothers, Richie Kamuca, Christian McBride, Joe Venuti, Shirley Scott, Jaleel Shaw, Luckey Roberts, Mary Ann McCall, Kenny Barron, Benny Golson, Philly Joe Jones and several Eubankses, to name perhaps ten-percent of the important players from that city. Rifftides reader Oliver Wunsch reports on a new development.

Ray Bryant, Red Rodney, the Heath brothers, Richie Kamuca, Christian McBride, Joe Venuti, Shirley Scott, Jaleel Shaw, Luckey Roberts, Mary Ann McCall, Kenny Barron, Benny Golson, Philly Joe Jones and several Eubankses, to name perhaps ten-percent of the important players from that city. Rifftides reader Oliver Wunsch reports on a new development.

That seems to be the way things are going, Mr. Wunsch. See this recent posting.I wanted to share a new site we JUST launched here at Painted Bride Art Center in Philly, that represents our own attempt to marry new media with the jazz compositional process, called Big Ears Philly. The site is a tool for John Hollenbeck and 12 Philly jazz musicians to communicate and refine ideas as they prepare to develop new work during their residency at Painted Bride. Each artist maintains a blog, can post video, and can share audio files of work in progress. It also is obviously designed to bring audiences into this process. So this is just a note to say check it out, and I've enjoyed your writing. We're really looking towards blogs as THE location for jazz journalism these days.

In Boston they ask, How much does he know? In New York, How much is he worth? In Philadelphia, Who were his parents? -- Mark Twain

The streets are safe in Philadelphia, it's only the people that make them unsafe.--Frank Rizzo

Yes, I'd like to see Paris before I die. Philadelphia will do.-- W.C. Fields in My Little Chickadee

Here lies W. C. Fields. I would rather be living in Philadelphia. -- Epitaph Fields proposed for himself

On election day, the Providence Journal ran two editorials concerning matters important to Rhode Islanders. One was about the governor's suggestion that it's time to end the state income tax (a questionable idea, the paper said). The other was on the death of pianist Dave McKenna, one of the state's cultural heroes. To read the Mckenna editorial, go here. Thanks to Rifftides reader Steve Caminis for calling it to our attention.

For the October 18 announcement of McKenna's death, video of him playing and reader comments, go to this Rifftides archive page.

Rifftides reader Ken Dryden writes:

It's funny, but I discovered Joe Sullivan the same way I found out about Meade Lux Lewis, when rocker Keith Emerson (of Emerson, Lake & Palmer) recorded one of his pieces, "Little Rock Getaway." Though there was very little in print of Sullivan's work under his own name in the early 1970s, I managed to find a couple of LPs. He was also one of the pianists featured in Ralph Gleason's Jazz Casual series, issued on a Koch CD with the Earl Hines performance and likely on DVD/VHS in the series.(In the Jazz Casual series, the Sullivan program is paired with one featuring cornetist Muggsy Spanier. -- DR)

This is Joe Sullivan's birthday. Although Rifftides posted an item about Sullivan and others only three months ago, it is never too soon to call him to the attention of listeners who may not have made the acquaintance of a man who inspired countless other pianists. Here is a Rifftides golden oldie.

This is Joe Sullivan's birthday. Although Rifftides posted an item about Sullivan and others only three months ago, it is never too soon to call him to the attention of listeners who may not have made the acquaintance of a man who inspired countless other pianists. Here is a Rifftides golden oldie.

It is not good enough simply to recycle an archive piece. As a double bonus, here are two versions of Sullivan's most famous composition, "Little Rock Getaway." The first is his 1933 Parlophone recording, the second the Decca recording from 1935, by which time he had shaped the famous melody line.

If Sullivan were alive, he would be 102 years old. He died on October 13, 1971.

In the scratch-scratch tradition of cross-referencing that is an important aspect of the blogosphere, Don Heckman has responded to the November 4 Rifftides piece about him, The Los Angeles Times and the general decline of writing about jazz in newspapers. That posting is two exhibits down the page. Heckman asks:

Do the complaints, the angry emails, the letters to the editor make a difference? Well, as Jake Barnes said to Lady Brett in The Sun Also Rises, "Isn't it pretty to think so."

To read Don's post, click here.

When I was in college and involved in the jazz community in Seattle, I helped to arrange a concert in my home town. Some of the musicians who traveled to the interior of the state to perform in that conservative agricultural community were black. One of my closest childhood friends came to the concert. Afterward, I took him to a party for the musicians. In the course of the socializing, I danced with a newer friend, the pianist Patti Bown. When I returned to the table, my old buddy told me, with considerable heat, he was ashamed that I had touched a black woman, although that was not the term he used to describe her.

I had not thought about that evening in decades. It came back to me last night as I listened to the next president of the United States speak to the world. I hope that my friend was watching, too.

Newspapers everywhere were retrenching even before the world financial crisis tetered on the edge of recession and finally fell into it. Declining readership and shriveling advertising revenue demanded cost-cutting. To no one's surprise, staff and space reductions claimed arts coverage early. When newsroom budgets start to shrink, cultural journalism is among the first targets because editors know that there will be relatively few complaints. In a world of minuscule and increasingly fragmented attention spans focused (ha) on hip-hop, Britney Spears and movies about high school musicals, jazz is even more a minority interest than string quartets, modern dance and bagpipe solos.

Jazz writers still appear sporadically in The Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, The New York Times, The Seattle Times and a few other major papers. Few of them are full-time staff employees. Free lance contributors who once covered live jazz and reviewed recordings regularly show up in print less and less often. Call it the Heckman phenomenon.

Until recently, Don Heckman, the jazz critic of The Los Angeles Times, wrote fairly often about jazz in and around the second largest city in the United States. At the beginning of his career at the Times, Heckman worked in tandem with Leonard Feather to provide readers with some of the most complete daily jazz coverage in the world. Like Feather, he was never a staff member. After Feather died in 1994 Heckman, an experienced musician, careful listener and talented writer, became the Times' chief jazz contributor. He still is, but the contributions are declining to the point of disappearance. Around the turn of the century, jazz coverage was put under the supervision of the Pop Music editor at the Times. What eventually happened is typical of the fate of jazz coverage at most American newspapers. Here is a little of what Heckman wrote recently on his blog about the current situation.

Until recently, Don Heckman, the jazz critic of The Los Angeles Times, wrote fairly often about jazz in and around the second largest city in the United States. At the beginning of his career at the Times, Heckman worked in tandem with Leonard Feather to provide readers with some of the most complete daily jazz coverage in the world. Like Feather, he was never a staff member. After Feather died in 1994 Heckman, an experienced musician, careful listener and talented writer, became the Times' chief jazz contributor. He still is, but the contributions are declining to the point of disappearance. Around the turn of the century, jazz coverage was put under the supervision of the Pop Music editor at the Times. What eventually happened is typical of the fate of jazz coverage at most American newspapers. Here is a little of what Heckman wrote recently on his blog about the current situation.

Several months ago, a new editor took over the reins of the Pop Music department from the acting editor. I was told, almost immediately, by her that jazz reviews would be reduced in number, and would essentially have to be pitched to her for approval That represented an immediate and significant change, since -- as one who is deeply aware of developments in jazz, here and elsewhere -- I had generally done my own scheduling of reviews, with oversight from the acting editor. In addition, the Sunday jazz record review spotlight disappeared.

In scheduling my reviews -- of both live concerts and recordings -- I tried to balance the major name programs with as much coverage as possible for the Southland's huge array of world class jazz talent. That approach became virtually impossible when the reviews were cut back to one a week. Within a month or two, they were cut to one every ten days. After that it became a matter of submitting events I thought were important, and hoping that coverage would be permitted. It usually wasn't.

About two or more months ago, I was advised that the free lance budget for Pop had run out for the year, and that I should contact my editor in late December to consider what could be covered when the new budget came into effect in January. Basically that meant that I could do no reviews for the last 3 1/2 months of the year.

Considering the concentration and frequency of jazz in Los Angeles and Orange counties, that dictum is an absurdity, but L.A. is far from the only place where jazz coverage is drying up. To see all of Heckman's posting and learn what besides music he heard when he covered the recent Thelonious Monk Jazz Competition, go here.

Not by the way, Mr. Heckman is devoting a substantial share of his time, energy and perceptiveness to a web log. That decision seems somehow familiar. I am adding a link to Here, There and Everywhere under Other Places in the center column.

How is the jazz coverage in your newspaper? Use the comment link below to reply. In your brief paragraph describing the situation, please include the names of your city and your paper.

Herb Geller is eighty years old today. The alto saxophonist was the performing guest of honor tonight in a tribute concert by the NDR (North German Radio) Big Band. From 1965 to 1993,

Geller was a star soloist of the NDR, one of the best large jazz aggregations in the world. The concert was in the NDR's venerable Rolf Liebermann studio. Since his mandatory retirement at sixty-five, Geller has been at least as busy as he was during the previous forty-seven years of his career. One of the major post-Charlie Parker alto soloists, he plays frequently in Europe and the United States. His most recent CD is Herb Geller At The Movies (Hep). His latest video is this one:

Geller was a star soloist of the NDR, one of the best large jazz aggregations in the world. The concert was in the NDR's venerable Rolf Liebermann studio. Since his mandatory retirement at sixty-five, Geller has been at least as busy as he was during the previous forty-seven years of his career. One of the major post-Charlie Parker alto soloists, he plays frequently in Europe and the United States. His most recent CD is Herb Geller At The Movies (Hep). His latest video is this one:

This video is one of three on You Tube showing Geller in 1972 rehearsing for a concert with the Bill Evans Trio in Germany. In it, he plays piccolo and flute. In the second video, he plays alto sax and flute and continues in this conclusion of the rehearsal sequence. Together, the three clips give us twenty-five minutes of four of the leading jazz players of their time preparing their music. These videos provide a precious opportunity to see Evans at once serious and relaxed in collaboration with a peer for whom he obviously had great respect.

Happy Birthday, Herb. Long may you wave.

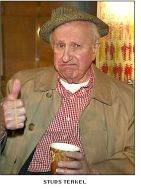

There is little or no mention of it in his obituaries, but Studs Terkel's first book was about jazz. The oral historian, broadcaster and master interviewer died yesterday in Chicago at ninety-six. Terkel won the Pulitzer Prize for his best-selling 1985 book The Good War: An Oral History Of World War II. Many of his other oral history books were also best sellers, beginning in 1967 with Division Street: America. He followed with Hard Times, Working and seven other books.

Even as he was acting in plays and doing his daily radio program, Terkel wrote a jazz column in a Chicago paper. He knew jazz in a wide range. His love and knowledge of it are plain in Giants of Jazz, published in 1957 when he was forty-five years old. The current running through the book is common to all of Terkel's work, the convictions that everything is part of everything else, that we're all in this together, that everyone's story is important. Giants of Jazz begins with King Oliver and concludes with the chapter called "John Coltrane, the Search Continues." Ending with Coltrane, Terkel reflected his awareness of what was brewing in jazz -- Coltrane was slightly known when Terkel wrote the book in 1956 -- and his vision of the direction in which the music was headed. Thomas Conner, music editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, captured that aspect of the book in a column in October of 2006.

Even as he was acting in plays and doing his daily radio program, Terkel wrote a jazz column in a Chicago paper. He knew jazz in a wide range. His love and knowledge of it are plain in Giants of Jazz, published in 1957 when he was forty-five years old. The current running through the book is common to all of Terkel's work, the convictions that everything is part of everything else, that we're all in this together, that everyone's story is important. Giants of Jazz begins with King Oliver and concludes with the chapter called "John Coltrane, the Search Continues." Ending with Coltrane, Terkel reflected his awareness of what was brewing in jazz -- Coltrane was slightly known when Terkel wrote the book in 1956 -- and his vision of the direction in which the music was headed. Thomas Conner, music editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, captured that aspect of the book in a column in October of 2006.

For example, the chapter on Louis Armstrong is sandwiched between the one about King Oliver (who mentored young Louis) and Bessie Smith (who was affected by the sound of Louis' horn); Smith's bio mentions the moment Bix Beiderbecke heard her sing, a moment that left him in awe -- and which figures into his own chapter, the next one. These links build a chain throughout the book -- mashing up with full force when Count Basie and Charlie Parker hit Kansas City, and then when Dizzy Gillespie meets Bird -- and they leave the impression that, yes, each individual was a formidable talent but, no, the opportunity for that talent to succeed did not present itself in a vacuum. These musicians were a part of something greater than themselves, and their own personalities amplified the human race as a whole. It's all part of a continuity.

To read all of Conner's column, go here.

Terkel spent 45 years broadcasting a daily hour of conversation, music and commentary on Chicago's WFMT. In 1980, he won a Peabody award for that work. Among the staff of the station, who admired his defiantly casual dress, his dedication and his irascibility, he had a special name: Free Spirit.

The headline on Terkel's obit in his hometown paper, The Chicago Tribune, is simply, STUDS. To read the obituary, go here. If you have fifteen minutes to spare, get the flavor of Terkel and his opinions by watching this video.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary