Rifftides: August 2008 Archives

The Detroit Jazz Festival is playing this Labor Day Weekend. One reason the four-day event is subtitled "A Love Supreme: The Detroit-Philly Connection" is the powerful legacy of bassists from those cities. In a sidebar piece leading up to the festival, Mark Stryker of The Detroit Free Press writes about their importance.

If it weren't for Detroit and Philadelphia, the history of modern jazz would be a lot shorter and a lot less hip. These two meccas are so similar in substance, style and the sheer number of musicians that rose from their streets to prominence that they could be twins separated at birth.

But when you narrow the focus specifically to bass players, the connections become even more striking. The roll call includes more gods per capita than from any other city.

"It's not an accident that almost all of my favorite bass players are from Detroit or Philadelphia," says Christian McBride, the Philadelphia-born bassist who serves as artist-in-residence at the 29th annual Detroit International Jazz Festival, which begins Friday and runs through Labor Day. "You take away Paul Chambers, Ron Carter, Percy Heath, Jimmy Garrison, James Jamerson, Alphonso Johnson and the others and you're left with a very short list."

Stryker's piece includes brief profiles of several of those bassists and others, with comments from McBride and video of two bassists in action. To read the whole thing, go here.

One of the things I like about jazz, kid, is I don't know what's going to happen next. Do you? -- Bix Beiderbecke

Finally Beiderbecke took out a silver cornet. He put it to his lips and blew a phrase. The sound came out like a girl saying 'yes'. -- Eddie Condon

...and all of a sudden Bix stood up and took a solo and I'm telling you those pretty notes went all through me.-- Louis Armstrong

Rifftides reader David Peterkofsky inquired about modern-day jazz marimba players. In the course of searching, I ran across a 1940s soundie with marimbists galore. This has little to do with jazz, but it's an opportunity to see a bass player who makes Chubby Jackson seem catatonic.

As for Mr. Peterkofsky's question, Bobby Hutcherson, Stefon Harris, Dave Samuels, Cal Tjader, Mike Mainieri, Emil Richards and Gary Burton have all used marimba as well as vibes. If readers have leads to other current marimba soloists, please use the comment link below to let us know.

Michael Weiss, Soul Journey (Sintra). Michael Weiss has been a pianist to follow since his impressive 1986 debut recording, Presenting Michael Weiss. As his career rolled out in work with Art Farmer, Johnny Griffin, Lou Donaldson, Tom Harrell and other major leaguers,

Weiss's talent as a composer became increasingly apparent. His writing received high-profile recognition when he won the 2000 BMI/Monk Institute Composers Competition grand prize for "El Camino." That is one of the pieces in Weiss's Soul Journey CD, which came out in 2003 but escaped my notice until a few weeks ago. Recorded with a band of youngish modern all-stars, Soul Journey is one of those rare latterday albums made up of original compositions during which I do not wish for the relief of standard material. Weiss's writing, like his piano playing, has roots in the bebop tradition. He seasons both with the spice of recent developments and the variety of his finely attuned ear and imagination.

Weiss's talent as a composer became increasingly apparent. His writing received high-profile recognition when he won the 2000 BMI/Monk Institute Composers Competition grand prize for "El Camino." That is one of the pieces in Weiss's Soul Journey CD, which came out in 2003 but escaped my notice until a few weeks ago. Recorded with a band of youngish modern all-stars, Soul Journey is one of those rare latterday albums made up of original compositions during which I do not wish for the relief of standard material. Weiss's writing, like his piano playing, has roots in the bebop tradition. He seasons both with the spice of recent developments and the variety of his finely attuned ear and imagination.

"El Camino" and "La Ventana" have strong Latin undercurrents. "Orient Express" draws on elements of John Coltrane's "Countdown." "Cheshire Cat" incorporates tricky time changes, challenging listeners

without confusing them. "Soul Journey" makes use of atmospheric harmonic and rhythmic elements and a Fender Rhodes piano that suggest familiarity with Herbie Hancock's crossoeuvre. On acoustic piano, Weiss folds inspiration from Bud Powell, Barry Harris and Tommy Flanagan into a thoughtful personal style that occasionally fizzes with exuberance, even whimsy. The sidemen interpreting Weiss's pieces are among the best of their generation -- Ryan Kisor, an unfailingly impressive trumpet soloist of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra; alto saxophonist Steve Wilson, a star of Maria Schneider's orchestra; the Art Blakey veteran Steve Davis, a trombonist who exults in taking harmonic chances; bassist Paul Gill and drummer Joe Farnsworth, rhythm stalwarts of the New York scene.

without confusing them. "Soul Journey" makes use of atmospheric harmonic and rhythmic elements and a Fender Rhodes piano that suggest familiarity with Herbie Hancock's crossoeuvre. On acoustic piano, Weiss folds inspiration from Bud Powell, Barry Harris and Tommy Flanagan into a thoughtful personal style that occasionally fizzes with exuberance, even whimsy. The sidemen interpreting Weiss's pieces are among the best of their generation -- Ryan Kisor, an unfailingly impressive trumpet soloist of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra; alto saxophonist Steve Wilson, a star of Maria Schneider's orchestra; the Art Blakey veteran Steve Davis, a trombonist who exults in taking harmonic chances; bassist Paul Gill and drummer Joe Farnsworth, rhythm stalwarts of the New York scene.

My only disappointment with the CD is the engineered fade ending on the title tune. Surely, a composer of Weiss's acuity could write his way to a conclusion. It is a tiny defect in a successful collection.

Ryan Kisor, Conception: Cool and Hot (Birds). Kisor is less well known than several trumpet and flugelhorn players who are his contemporaries but not his creative equals. On any given

night, he is likely to take solo honors from the other trumpeters in the LCJO -- all of the others. In his initial CD for a new Japanese label, Kisor's front line partner is alto saxophonist Sherman Irby, another Lincoln Center member. On Gerry Mulligan's "Line For Lyons," Irby's entertaining solo, an exercise in self-conscious pointillism, contrasts dramatically with Kisor's relaxed flugelhorn choruses. In "Lyons," Kisor somehow manages at once to suggest and avoid Chet Baker. Nor does he literally appropriate Miles Davis in "Conception," although it may impossible for any trumpeter not to allude to Davis in pieces so firmly associated with him as "Conception" and J.J. Johnson's "Enigma. The title tune, full of scalar hills and dales adroitly negotiated by the horns, is Kisor's only original composition here.

night, he is likely to take solo honors from the other trumpeters in the LCJO -- all of the others. In his initial CD for a new Japanese label, Kisor's front line partner is alto saxophonist Sherman Irby, another Lincoln Center member. On Gerry Mulligan's "Line For Lyons," Irby's entertaining solo, an exercise in self-conscious pointillism, contrasts dramatically with Kisor's relaxed flugelhorn choruses. In "Lyons," Kisor somehow manages at once to suggest and avoid Chet Baker. Nor does he literally appropriate Miles Davis in "Conception," although it may impossible for any trumpeter not to allude to Davis in pieces so firmly associated with him as "Conception" and J.J. Johnson's "Enigma. The title tune, full of scalar hills and dales adroitly negotiated by the horns, is Kisor's only original composition here.

For the rest, he plays jazz classics and standards. Irby's Cannonball Adderley verve on "You Stepped Out of a Dream" is a high point. Wisely, Kisor follows Irby by opening his solo with long tones, then rebuilding the excitement. Pianist Peter Zak's touch commands attention in

his solo on this piece. On "I Remember You," Kisor uses what sounds like a straight mute, all but disappeared in modern jazz. He solos with intimacy, then intricacy worthy of Dizzy Gillespie. "All the Things You Are" gets standard, but by no means routine, treatment. Kisor is a bit more distant from the microphone on this track, his sound thinner than on the other pieces, but his strong conception influences the tack of Irby's solo. There's a good deal of listening to one another among the musicians in this satisfying set. The rhythm section is bassist John Webber, drummer Willie Jones III and Zak, a young pianist to keep your ear on.

his solo on this piece. On "I Remember You," Kisor uses what sounds like a straight mute, all but disappeared in modern jazz. He solos with intimacy, then intricacy worthy of Dizzy Gillespie. "All the Things You Are" gets standard, but by no means routine, treatment. Kisor is a bit more distant from the microphone on this track, his sound thinner than on the other pieces, but his strong conception influences the tack of Irby's solo. There's a good deal of listening to one another among the musicians in this satisfying set. The rhythm section is bassist John Webber, drummer Willie Jones III and Zak, a young pianist to keep your ear on.

The $27.00 price tag from Eastwind Imports seems high, but not in comparison with the $47.98 that Amazon.com is asking. You could buy almost a full tank of gas for that.

To see and hear Kisor featured with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, go here.

Readers in and around New York City may be interested in this announcement sent by Michael Weiss.

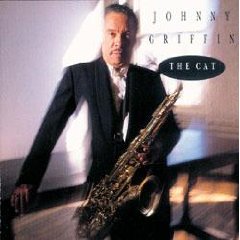

CELEBRATING JOHNNY GRIFFIN: A TRIBUTE IN WORDS AND MUSIC

Reminiscences from fellow musicians, family and friends.

Johnny Griffin's compositions performed by Johnny's longtime rhythm section (Michael Weiss, John Webber and Kenny Washington) with Eric Alexander. Additional performances by Jimmy Heath, Cedar Walton, Ray Drummond and Ben Riley.

SEPTEMBER 14, 2008, 7 p.m.

St. Peter's Church

619 Lexington Avenue at 54th Street New York, NY

The tenor saxophonist died a month ago at his home in France.

The recent Rifftides item about the continuing medical needs of Bix Beiderbecke biographer Richard M. Sudhalter brought interesting comments about both men. You can read it and the comments here. The piece stimulated a correspondence with Paul Paolicelli, blog reader, fellow survivor of the news business and former lead trumpet player. Leaving out parts concerning unproved and unprovable allegations about Beiderbecke's personal life, here are key parts of the exchange, which expanded with a contribution from trumpeter Randy Sandke revised and forwarded by Sue Fischer of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Society in Davenport, Iowa.

Paolicelli:

Thanks to a long conversation with Sudhalter years ago, I reevaluated my once complete adoration of Beiderbecke, that 27-year-old drunk. I was a member of the Pittsburgh Jazz Society as a kid and had a considerable collection of old 78s from the Jean

Goldkette/Howdy Quicksell/Paul Whitman era. I think now that Beiderbecke's contribution has been completely overstated because he was the "great white hope" of that era and, while certainly inventive and interesting, not quite the genius I once thought. So, my adult evaluation of him is as an out-of-control self-destructive alcoholic with a solid but undisciplined talent. Common sense tells you that people don't die at 27 of natural causes. He wasn't a stable citizen. He might have played his way into a footnote had he lived.

I should also point out that the very first CD I ever bought was a Beiderbecke compilation, years after my 78s had been stolen. It's just that after my conversation with Dick and knowing more about Bix's outlandish personal behavior, I abandoned my idolization. I'm back to Louis Armstrong. In Rome, a jazz saxophonist was doing a workshop with our group. I was the lead trumpet. He asked me who I thought of when I thought of trumpet players. I told him there were too many to even try and remember. He said, "If you had to pick just one, who would it be?"

"Louis Armstrong," I replied.

"Man that was a long time ago," he said.

"Yeah," I said, "And so was Shakespeare. But if you're going to speak the English language you'd better damn well know something about him."

Ramsey:

Beiderbecke's playing profoundly affected many people in many ways. He influenced Rex Stewart, Lester Young, Bobby Hackett, Hoagy Carmichael and Bing Crosby, to name a few. It is well documented that Armstrong understood, admired and was moved by Bix's talent. The man who created the tag to "I'm Coming, Virginia," to single out one stunning moment from his discography, was a genius of spontaneous lyrical creation. The multiplier effect of his example is enormous. I'm sorry that he was a boozer and a psychological mess. Nor am I happy about Poe's laudanum addiction, Lord Byron's bisexuality and moral vacuousness, Charlie Parker's heroin habit and satyrism, or Chet Baker's self-centered, self-destructive life. I will continue to read Poe and Byron and listen to Bird, Chet and Bix, and be amazed.

Randy Sandke:

The cause of Bix's problems may be even more elementary and tragic. With the advent of prohibition in January 1920, the simple act of taking a drink containing alcohol became a criminal offense. Bootleg liquor became a witch's brew that could contain poisonous ingredients. A sample sold in the streets of Harlem was taken to a lab and analyzed. It was found to contain wood alcohol, benzene, kerosene, pyridine, camphor, nicotine, benzol, formaldehyde, iodine, sulphuric acid, soap, and glycerin. People who consumed this hazardous concoction often experienced dizziness, blackouts, hair loss, fluctuations in weight, advanced aging, partial blindness and paralysis. It is known that Bix exhibited most if not all of these symptoms.

Paolicelli:

Rifftides readers unfamiliar with Beiderbecke's playing will find plenty of it in this seven-CD box set that also features his saxophone partner Frank Trumbauer and many of the greatest early recordings of trombonist Jack Teagarden. This single CD is a good sampler of some of Beiderbecke's best-known work, including "I'm Coming, Virginia" and "Singin' The Blues."Just as a by-the-way; don't buy into the "my father didn't love me so I had to drink and destroy my talent and life" theory. There are lots of us who found our way out of that morass; first by stopping drinking and then by taking an inventory and changing our lives. We don't buy the self-pitying "poor me" BS any more than you should. A drunk has a disease. The first step in curing it is simple recognition that it's beyond the individual's control. That's an especially complicated step in the talented (Poe, Parker, Byron and Baker, just to list a few p's and b's) or wealthy. They are surrounded by sycophants or enablers who don't know how or don't have the will to confront them. And there's that ridiculous theory that "it's part of their art." Alcoholism is alcoholism. A relationship with a father is a relationship with a father. Bix's father, from all I've read, was terribly disappointed in his son's choices. I think the music was more a symbol of his disappointment and that the broader issue was really his son's immaturity, lack of self control, and dreadful drinking bouts that the father probably blamed on the musician's life, again not understanding the fundamental nature of his son's disease. In those days a respectable citizen just didn't get drunk. (Same way today in Italy; it's not a bella figura. Thus, alcoholics tend to drink privately, which adds to the problems. The Italian AA program is purely word of mouth).

...Fellow artsjournal.com blogger Terry Teachout has the kind of news every author welcomes. To share it, go here...and be sure to watch the celebratory video of Terry's subject in glorious action.

Congratulations, TT. I know how good it feels.

John Coltrane

In the August 21 Wall Street Journal, Nat Hentoff tells of a New York second grade teacher, Christine Pasarella, who uses John Coltrane as a classroom role model in her work of drawing out the intelligence of her students. He reports Mrs. Pasarella saying that when she played Coltrane's recordings...

In the August 21 Wall Street Journal, Nat Hentoff tells of a New York second grade teacher, Christine Pasarella, who uses John Coltrane as a classroom role model in her work of drawing out the intelligence of her students. He reports Mrs. Pasarella saying that when she played Coltrane's recordings...

"...the children were drawn to the range of feelings in the songs as I gave them the backgrounds of the compositions.

"'Alabama,' for example, was about Martin Luther King and racial discrimination; and while 'My Own True Love' concerned a man and a woman, John Coltrane's 'Love Supreme' expressed a love for humanity."

Hentoff writes:

This reminded me that in one of my conversations with Coltrane he said he was searching for the sounds of what Buddhists call "Om," which he described as the universal essence of all of us in the universe. He also told me regretfully, "I'll never know what the listeners feel from my music, and that's too bad."

Ms. Passarella's second-grade students, she says, would have told him how moved they were by not only the ballads "but the more avant-garde recordings, such as 'Interstellar Space.'" She notes that, through her teaching, "I have discovered that young children have open, welcoming minds, and the more pure and emotional the music, the more they connect. Soon they were hooked on John Coltrane's music."

When the students learned that Coltrane's home was not far from their school, they became even more interested. To read all of Hentoff's column, click here.

Bud Shank

All About Jazz reports that Against The Tide, the documentary about alto saxophonist Bud

Shank, has won a major film making award. Rifftides discussed the film in April. From the AAJ story:

Shank, has won a major film making award. Rifftides discussed the film in April. From the AAJ story:

The Telly Awards honor the very best local, regional, and cable television commercials and programs, as well as the finest video and film productions, and work created for the Web.

To read it all, go here.

Rifftides World Headquarters has welcome summer visitors and resounds with telecasts of Olympics events. Nonetheless, the staff makes time for listening. We don't award medals, but here are brief impressions of four recent CDs that placed high with the judges.

Danilo Perez, Across The Crystal Sea (EmArcy). Inevitably, this collaboration of the pianist

with Claus Ogerman recalls Bill Evans With Symphony Orchestra (1965), which Ogerman also arranged. More than half of the themes come from classical composers--de Falla, Rachmaninoff, Massenet, Sibelius, Distler. Ogerman's "Another Autumn" holds its own in that heavy company. Perez's playing is shaded with subtlety, showing a distinct Evans leaning in touch, chord voicings and development of melodic lines. On two tracks, "Lazy Afternoon" and "(All of a sudden) My Heart Sings," Cassandra Wilson sings simply and beautifully.

with Claus Ogerman recalls Bill Evans With Symphony Orchestra (1965), which Ogerman also arranged. More than half of the themes come from classical composers--de Falla, Rachmaninoff, Massenet, Sibelius, Distler. Ogerman's "Another Autumn" holds its own in that heavy company. Perez's playing is shaded with subtlety, showing a distinct Evans leaning in touch, chord voicings and development of melodic lines. On two tracks, "Lazy Afternoon" and "(All of a sudden) My Heart Sings," Cassandra Wilson sings simply and beautifully.

The Modernity of Bob Brookmeyer: The 1954 Quartets (Fresh Sound). Finally, the first of the valve trombonist's dates with pianist Jimmy Rowles, bassist Buddy Clark and drummer Mel

Lewis is on CD. Originally on Norman Granz's Clef label, this remains one of the great soloist-plus-rhythm-section encounters of the second half of the twentieth century. Six years later, they reassembled for the equally successful The Blues Hot and Cold (Verve), which has yet to make it to compact disc. The second session here is another superb 1954 Brookmeyer quartet, originally on the Pacific Jazz label, with pianist John Williams, Red Mitchell or Bill Anthony on bass and the remarkable drummer Frank Isola. This combination release is a basic repertoire item.

Lewis is on CD. Originally on Norman Granz's Clef label, this remains one of the great soloist-plus-rhythm-section encounters of the second half of the twentieth century. Six years later, they reassembled for the equally successful The Blues Hot and Cold (Verve), which has yet to make it to compact disc. The second session here is another superb 1954 Brookmeyer quartet, originally on the Pacific Jazz label, with pianist John Williams, Red Mitchell or Bill Anthony on bass and the remarkable drummer Frank Isola. This combination release is a basic repertoire item.

Jan Lundgren,

Soft Summer Breeze (Marshmallow). In his ninth CD for the Japanese label, the Swedish pianist applies to standards by Ellington, Monk, Shearing, Porter and Berlin and others his distinctive touch and ingenuity with chords. Lundgren, bassist Jesper Lundgaard and drummer Alex Riel include superior interpretations of two rarely-played jazz classics, Al Cohn's "Tasty Pudding" and Tadd Dameron's "Soul Train." Lundgren opens with an unaccompanied "Mood Indigo" that emphasizes his continuing accumulation of harmonic wisdom. More of his ingeniuty with chord voicings is on display in his introduction to "Darn That Dream" and his solo on the half-forgotten Eddie DeLange ballad "Velvet Moon."

Soft Summer Breeze (Marshmallow). In his ninth CD for the Japanese label, the Swedish pianist applies to standards by Ellington, Monk, Shearing, Porter and Berlin and others his distinctive touch and ingenuity with chords. Lundgren, bassist Jesper Lundgaard and drummer Alex Riel include superior interpretations of two rarely-played jazz classics, Al Cohn's "Tasty Pudding" and Tadd Dameron's "Soul Train." Lundgren opens with an unaccompanied "Mood Indigo" that emphasizes his continuing accumulation of harmonic wisdom. More of his ingeniuty with chord voicings is on display in his introduction to "Darn That Dream" and his solo on the half-forgotten Eddie DeLange ballad "Velvet Moon."

Derrick Gardner, A Ride To The Other Side (Owl). If the title leads you to expect free jazz,

forget it. This young trumpeter and his group, The Jazz Prophets, will remind you of Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Bill Hardman and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, and perhaps the Farmer-Golson Jazztet. Mainstream hard blowing contrasts with post-bop ballad relief in Gardner's "God's Gift" and "Just A Touch." There is fine playing throughout by all hands, with exceptional work by Gardner, trombonist Vincent Gardner and pianist Anthony Wonsey.

forget it. This young trumpeter and his group, The Jazz Prophets, will remind you of Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Bill Hardman and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, and perhaps the Farmer-Golson Jazztet. Mainstream hard blowing contrasts with post-bop ballad relief in Gardner's "God's Gift" and "Just A Touch." There is fine playing throughout by all hands, with exceptional work by Gardner, trombonist Vincent Gardner and pianist Anthony Wonsey.

More reviews to come. In the meantime, your comments, please.

Film animation married to jazz improvisation goes back to the 1930s and the advent of sound films. This collaboration of the cartoon figure Betty Boop and the real Louis Armstrong is one of the most famous early examples. Social sensitivity was not a consideration.

In 1949, the art advanced--or at least changed--dramatically when two Canadians, painter Norman McLaren and pianist Oscar Peterson, got together. They made Begone Dull Care, in which McLaren painted and otherwise altered the surface of film stock to create a classic abstract visual expression of the Peterson trio's music.

For an analysis of the technique McLaren used in Begone Dull Care, read this essay by Paul Melancon.

In this century, the Israeli artist Michal Levy, who is also a saxophonist, was inspired by John Coltrane to construct animation reflecting her conviction that "the structural approach of Coltrane to music is associated with architectural approach. The musical theme defines a space and the musical improvisation is like someone drifting in that imaginary space." She chose as her vehicle the beginning and ending theme and Coltrane's solo from the 1959 recording of "Giant Steps."

To see another film animation by Michal Levy, to music by the avant garde pianist and composer Jason Lindner, go here.

Last month, Michaëlle Jean, Governor General of Canada, named pianist Paul Bley a member of the Order of Canada, the nation's highest civilian honor. The official announcement cited him for "his contributions as a pioneering figure in avant-garde and free jazz, and for his influence on younger jazz pianists."

Bley was at the center of changes in jazz in the late l950s. The Canadian pianist has continued for half a century as an instigator of  transformation. At the same time, he has been a gravitational force helping to restrain unstructured or loosely structured jazz from flying off into space as random noise. He is pictured recently at the right and below as a young man. The sidemen in Bley's Los Angeles band of 1958 and '59 were alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Billy Higgins. They became the Ornette Coleman Quartet, providers of oxygen to fire up the free jazz movement that had been smoldering for a decade. Recordings of Bley's band at the Hillcrest Café are reissued on CD under Coleman's name.

transformation. At the same time, he has been a gravitational force helping to restrain unstructured or loosely structured jazz from flying off into space as random noise. He is pictured recently at the right and below as a young man. The sidemen in Bley's Los Angeles band of 1958 and '59 were alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman, trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Billy Higgins. They became the Ornette Coleman Quartet, providers of oxygen to fire up the free jazz movement that had been smoldering for a decade. Recordings of Bley's band at the Hillcrest Café are reissued on CD under Coleman's name.

Thanks to Rifftides reader Brian Nation of the Vancouver, B.C., Jazz Society for directions to a transcribed conversation with Bley. On the Vancouver Jazz Society's web site, Bley tells soprano saxophonist Bill Smith that after the groundbreaking job at the Hillcrest, he had a band with bassist Scott LaFaro and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson. After a time, he felt compelled to return east just as, earlier, he felt compelled to leave Canada. Here is an excerpt from what he tells Smith about his 1959 visit to Massachusetts and the effect it had on his career. He made the trip with his wife Carla (they later parted), also a pianist and composer:

Ornette and Don had gone to Lennox School of Jazz and I'd done a couple of months at this club. I'd heard that they were at Lennox and that this was the final year of Lennox and I thought it was a very exciting idea. So one night around 9:30 I told the band that I was going to say goodbye to them right now, and that they could finish the year without me. I j

ust walked out of the club, got in a car with Carla and we drove directly non-stop to Lennox. We realized that if we drove non-stop we would get there for the last day of Lennox and we thought that it was extremely important to do this. After the Hillcrest job I was in the process of taking in this new information and playing with other musicians in Los Angeles. At the same time as working steadily I would go on my night off and sit in with everybody to see how I could relate what I'd learned with other players. After being offered every job in Los Angeles as well as having my own job, it was another case of having to leave. It was Montreal all over again. There was nothing left to accomplish.

We drove to Lennox. Got there at 10 or 11 o'clock at night. Got to the jam session of the final night. This was the last jam session of the last night of the final year of Lennox. Everything was the last. The last set and the last tune. The car was still sweating from the trip. We left everything in the car, came in and I tapped Ran Blake on the shoulder, introduced myself to him and said "May I sit in?" Ran is an extremely social, wonderful person, and said yes. I had a chance to play with whoever it was. Sort of an all-star line-up. Everybody was there. Jimmy Giuffre was there, Ornette, everybody was there. I had a chance once again to see if I could relate what I'd learned. Because I was playing a tempered instrument, you see, so that if anybody was to ask what was going on in free music I was in a perfect position to tell them something that they could relate to, because they could not relate to any information regarding microtonal music.

But they could relate to everything involving the well tempered scale. I had one tune to play and I played like my life depended on it. I've only done that about four times in my life, where you play one song where your life depended on it And in fact it did. That last tune on the last set led to my next four years' employment in New York. I got the job with Jimmy Giuffre based on that set. I got the job with George Russell based on that set; the two piano album. There was a phone call directly from his being in the audience that night. For Jazz in the Space Age with Bill Evans and myself and the orchestra. I got reinvited to play with Charles Mingus as a direct result of that set. Everything but the Sonny Rollins job was all out of that set. If a traffic light had been red instead of green at one intersection across the country it would have been too late. We slept under John Lewis' piano that night and headed for New York the next morning.

To read all of the long transcription of Bley's interview with Bill Smith, click here.

For more on the advent of Ornette Coleman, see this and this from the Rifftides archive.

Miles From India (Times Square). Producer Bob Belden wound up a monumental series of Miles Davis reissue box sets for Sony/Columbia, then he and fellow arranger Louiz Banks turned to interpreting the trumpeter's  immense output of recordings after 1959. This two-CD set considers the intersection of Indian music with Davis's adventures in scales and modes from Kind of Blue forward. Belden laid down the initial tracks in India, later adding soloists in New York. Among the players are sidemen from several Davis bands. They include Ron Carter, Jimmy Cobb, Gary Bartz, Chick Corea and David Liebman. Trumpeter Wallace Roney evokes Davis. Guitarist John McLaughlin contributes the brilliant title track. This ambitious project is a success.

immense output of recordings after 1959. This two-CD set considers the intersection of Indian music with Davis's adventures in scales and modes from Kind of Blue forward. Belden laid down the initial tracks in India, later adding soloists in New York. Among the players are sidemen from several Davis bands. They include Ron Carter, Jimmy Cobb, Gary Bartz, Chick Corea and David Liebman. Trumpeter Wallace Roney evokes Davis. Guitarist John McLaughlin contributes the brilliant title track. This ambitious project is a success.

Norma Winstone, Distances (ECM). The British singer places the purity of her voice, intonation and phrasing in the spare setting of Glauco Venier's piano and Klaus Gesing's soprano sax. Winstone's songs include that rarity, a successful vocal version of John Coltrane's "Giant Steps," and pieces by Cole Porter, Eric Satie, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Peter Gabriel. She uses her artistic range to bring disparate compositional styles into a collection not unlike a suite. Winstone comes close to jauntiness in her calypso sparring with Gesing's bass clarinet in "A Song for England," but the pervasive characteristics of this recital of vocal chamber music are peacefulness and emotional depth.

Norma Winstone, Distances (ECM). The British singer places the purity of her voice, intonation and phrasing in the spare setting of Glauco Venier's piano and Klaus Gesing's soprano sax. Winstone's songs include that rarity, a successful vocal version of John Coltrane's "Giant Steps," and pieces by Cole Porter, Eric Satie, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Peter Gabriel. She uses her artistic range to bring disparate compositional styles into a collection not unlike a suite. Winstone comes close to jauntiness in her calypso sparring with Gesing's bass clarinet in "A Song for England," but the pervasive characteristics of this recital of vocal chamber music are peacefulness and emotional depth.

Johnny Griffin & Lockjaw Davis, Live in Copenhagen (Storyville). The hard-charging tenor saxophonists worked in tandem for twenty-six years. This 1984 club date at the Montmarte club two years before Davis's death is typical of the unremitting swing and visceral excitement of their live appearances. The rhythm section is pianist Harry Pickens, bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Kenny Washington, in his mid-twenties and formidable. Griffin's blues "Call It Whatcha Wanna" is a highlight in a set that is itself a highlight. Now that Griffin has joined Davis, this is a memento of one of the great jazz partnerships.

Johnny Griffin & Lockjaw Davis, Live in Copenhagen (Storyville). The hard-charging tenor saxophonists worked in tandem for twenty-six years. This 1984 club date at the Montmarte club two years before Davis's death is typical of the unremitting swing and visceral excitement of their live appearances. The rhythm section is pianist Harry Pickens, bassist Curtis Lundy and drummer Kenny Washington, in his mid-twenties and formidable. Griffin's blues "Call It Whatcha Wanna" is a highlight in a set that is itself a highlight. Now that Griffin has joined Davis, this is a memento of one of the great jazz partnerships.

luxurious existence in Malibu during his final years ("I have everything I want in life") contrasts with a visit to his boyhood home in Vienna and his account of surviving an Allied bombing in 1944. The sequences featuring the last edition of The Zawinul Syndicate illustrate his charisma and power as a leader. Director Mark Kidel's videography, editing and sound mixing give the production a human heart.

luxurious existence in Malibu during his final years ("I have everything I want in life") contrasts with a visit to his boyhood home in Vienna and his account of surviving an Allied bombing in 1944. The sequences featuring the last edition of The Zawinul Syndicate illustrate his charisma and power as a leader. Director Mark Kidel's videography, editing and sound mixing give the production a human heart.

Dick Wimmer, The Wildly Irish Sextet (Soft Skull Press). Following the elemental Seamus Boyne (Irish Wine: The Trilogy) into the genius painter's old age, Wimmer cuts his creation no senior citizen slack. Boyne is wilder, more famous and more self-centered than ever. Still, he manages to maintain his loved ones' and the reader's affection as he rampages through New York, Westchester, Long Island and much of Ireland. You wouldn't want him as a house guest, but he's a great drinking buddy. The novel has a manic rhythm that surmounts every suspension of belief that such a character could exist.

Dick Wimmer, The Wildly Irish Sextet (Soft Skull Press). Following the elemental Seamus Boyne (Irish Wine: The Trilogy) into the genius painter's old age, Wimmer cuts his creation no senior citizen slack. Boyne is wilder, more famous and more self-centered than ever. Still, he manages to maintain his loved ones' and the reader's affection as he rampages through New York, Westchester, Long Island and much of Ireland. You wouldn't want him as a house guest, but he's a great drinking buddy. The novel has a manic rhythm that surmounts every suspension of belief that such a character could exist.

At eighty, Herb Geller is playing alto saxophone even better than when he was a key jazz figure in the 1950s and '60s. He is performing not with the gravity of Brahmsian old age but with full vigor. Nor has he lost the force of his convictions, witness this political song for which he wrote words and music.

In the interest of fairness, the Rifftides staff searched long and hard on the internet for John McCain campaign music to balance Geller's Obama production. It seems that no jazz artist has come up with a McCain song. This was the closest thing we found to a serious pro-McCain campaign ditty. Like Geller's, it is not an official campaign song.

Back to Herb Geller, the nonpolitical version. He has lived in Germany for decades and travels throughout Europe playing with a variety of rhythm sections. Last fall he was in Lisbon, Portugal. To see him in action and hear his solo on "Come Rain or Come Shine," click here. Unfortunately, the YouTube video ends just as a young guitarist starts to develop an interesting solo.

A British company is releasing a two-CD package tracing Bix Beiderbecke's influence on musicians of his era. Proceeds from sale of the set will be devoted to medical care of Dick Sudhalter, a musical descendant of Beiderbecke and his greatest biographer. Sudhalter is in bad health with MSA (muscular system atrophy) and getting worse. He needs help. From the Jass Masters news release:

For details about the 51 tracks in the CD set and for ordering information, click here. For a Rifftides posting about Sudhalter, his predicament and the benefit concert for him nearly two years ago, click here. He needed help then. Now, he needs it even more.The CD set contains a number of tracks that are being re-issued for the first time since their original release on 78 rpm record. In addition, several sides are transferred from un-issued test pressings and are being released for the first time ever. The recordings have

been faithfully restored using the latest digital techniques while at the same time paying respect to sound of the original recordings. The CD set is completed by two in-depth booklets (one of 28 pages and one of 36 pages) outlining each track and providing detailed information on the bandleaders and musicians responsible for the music heard on each CD; both booklets are replete with many rare photographs, some reproduced in print for the first time.

All profits from this CD set will go towards helping to meet the medical expenses for respected author and jazz musician Richard Sudhalter, who has done much

to bring Bix's life and music to wider audiences. His works include Bix, Man and Legend, which was written in collaboration with Philip R. Evans and first published by Arlington Press in 1974, Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915-1945, (Oxford University Press, 1999) and Stardust Melody: The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael (Oxford University Press, 2002). Sudhalter is also a much acclaimed musician whose Bix-influenced cornet and trumpet solos have graced numerous recordings.

It is now called the JVC Jazz Festival, but it still takes place in Newport, Rhode Island. If the festival no longer has the jazz purity of its beginnings in the 1950s, at least it has survived. It continues to include major jazz artists among the tangential pop figures who attract the big crowds that pay the bills. In today's Boston Globe, Steve Greenlee summarizes the two days of Newport and evaluates the highlights as if he were scoring Olympic events.

Gold medal: Sonny Rollins. The titan of the tenor sax hadn't played Newport in more than 40 years, but last night he owned it, with a hard-blowing set that closed the festival. He improvised endlessly on the repeating two-bar figure that serves as the framework of "Sonny Please." He played ahead of time and against time, punctuating phrases with quick jabs, shrieks, and honks. Be it burner or ballad, he blew and blew, and he never ran out of ideas.

Greenlee even awards gold, silver and bronze medals to elements of the audience.To read his entire report, click here.

In an interview a few days before the Newport performance, Rollins told Rick Massimo of the Providence Journal why he has kept bassist Bob Cranshaw in his band for more than four decades...

...because he maintained the fixed portion of it, and that would allow me to extemporize freely and the song would still be maintained. It was a contrast; if he had the fixed part, then I could go into all of my wild dreams.

...and why he rarely works with pianists.

At the risk of alienating my piano-playing friends -- and I've played with some great piano

players -- the piano is a very dominating instrument. I guess this goes back to when I was 7 years old and I was able to play and get into myself without any other instrument. The jazz bands in New Orleans -- you see these guys marching down the street, there's no piano...

The kind of music without a piano is more gritty, more real, hard jazz. It allows me to feel more free in my improvisations. The piano is very leading. You can lead a band here, you can lead to this chord, this mood. Everything is fed by a piano. I find that very restricting.

For more of the Massimo interview, go here.

For classic examples of Rollins not being led or fed by a piano, listen to A Night At The Village Vanguard and Way Out West, both from 1957 and as fresh as this morning.

The Frishberg, Sullivan, Wellstood item in the next exhibit brought quick responses from two men who knew Wellstood well. The first was Ted O'Reilly, the Toronto broadcaster who produced a few Wellstood recordings.

Wellstood was one of the brightest men I ever met, never mind how great a pianist he was. And great he was, and not afraid to play the way he did: as a stride/swing player in the bop era, and do it so well! (I've thought of him as the Ruby Braff of the piano...) I think I made more records with Wellstood at the piano than anyone else -- two with reedman Jim Galloway, two solo releases, and Stridemonster, piano duets with Dick Hyman. I'm glad I knew him, and wish he were still around.

Dave Frishberg wrote:

Did you know Wellstood? I did, although our paths crossed only infrequently. In the early '60s, my wife Stella (whom you met in New Orleans) and I stayed with Kenny Davern for a couple of days in Brielle NJ, where he and Wellstood played on a boat. One morning, Dick and Kenny and I played with gloves, bat and ball on a big athletic field. All three of us threw our arm(s) out. That was the day I got to know Wellstood, watched him play the piano at his cottage.

Wellstood was always one of my idols, although I never tried to play like him. He was a schooled pianist who could play Chopin, Bach, etc. One night I took Ben Webster (who was a piano freak) to hear Wellstood play solo at a jazz club around the corner from the Metropole. Ben was knocked out, gave Wellstood an enthusiastic hug and many shouts of approval. Also in the audience was Louis Armstrong (!) and party, and I was introduced to him twice at his table by both Wellstood and Webster. A memorable evening for me. I think the club was in the 40s between Fifth and Seventh Aves, a jazz club that popped up and soon disappeared.

Dick was a brilliant guy, brilliant like Dick Sudhalter, and undoubtedly among the best writers of all jazz musicians, a humorist on a very high level. You must have that Jazzology 2CD set of The Classic Jazz Quartet, and you probably remember the liner notes that each of those guys wrote: Joe Muranyi, Marty Grosz, Sudhalter, and Wellstood -- they all write beautifully. Wellstood's writing reminds me of Woody Allen and SJ Perelman. By the way, that's a recording I go back to listen to pretty often. There's another CD on Arbors of Dick playing solo in Dublin that I think is Wellstood at the top of his game.

Now that Dave asks, yes, I knew Wellstood. We became acquainted through the mail. In the 1960s, he sent me an indignant and very funny post card about my review of one of his records, quoting the offending line. By return mail, I pointed out that he had misread and misquoted the line. He then sent a letter of apology, also funny.

We got together occasionally during my New York years in the first half of the seventies. After the late newscast, I frequently went to Hanratty's on Second Avenue to hear him. Once, I took Paul Desmond. Desmond was delighted by his playing. Wellstood was surprised and flattered that Desmond came to hear him. Dick came to our table during his breaks. I anticipated scintillating exchanges between two world-class wits, but they just sat there complimenting one another.

We got together occasionally during my New York years in the first half of the seventies. After the late newscast, I frequently went to Hanratty's on Second Avenue to hear him. Once, I took Paul Desmond. Desmond was delighted by his playing. Wellstood was surprised and flattered that Desmond came to hear him. Dick came to our table during his breaks. I anticipated scintillating exchanges between two world-class wits, but they just sat there complimenting one another.

During a listening session one afternoon, I played Gerry Mulligan the Wellstood album called Alone. Mulligan was impressed by Dick's composition "Dollar Dance" and his playing on it. I suggested that the two of them should record it together. Mulligan liked the idea. So did Dick, and for a while it seemed that they were going solve contract issues and find a way to make a duo album. That was my one venture into musical match-making. The date never happened. I can still hear in my mind how the two of them would have hit if off.

As Frishberg indicated, Wellstood was a gifted pianist who could handle the classics, and jazz up to, through and beyond bebop. He could play anything. He preferred traditional styles. He was the first stride pianist, maybe the only one, to take on John Coltrane's modern harmonic obstacle course "Giant Steps." He recorded it in 1975, when it was still mystifying much of the jazz world. He tore it up. It's on his CD This Is The One...Dig!

As Frishberg indicated, Wellstood was a gifted pianist who could handle the classics, and jazz up to, through and beyond bebop. He could play anything. He preferred traditional styles. He was the first stride pianist, maybe the only one, to take on John Coltrane's modern harmonic obstacle course "Giant Steps." He recorded it in 1975, when it was still mystifying much of the jazz world. He tore it up. It's on his CD This Is The One...Dig!

I'm with Ted O'Reilly. I wish Wellstood were still around.

Dick Wellstood has been on my mind. Maybe it's because I heard Dave Frishberg play the piano the other night at The Seasons. Frishberg was in concert singing his inimitable songs and accompanying himself, but he opened up plenty of space for piano solos. Before he became famous for performing his songs, Frishberg worked with Zoot Sims, Al Cohn, Ben Webster, Jack Sheldon and Carmen McRae, among other demanding leaders. He was, and is, a versatile and idiosyncratic pianist who wraps several jazz eras into a style of his own. A couple of times on Saturday night, he pulled off stride passages that Wellstood would have appreciated.

In the mid-1940s when Wellstood was a young man working toward a career as a pianist, he was under the spell of Joe Sullivan (pictured). Sullivan (1906-1971) came from Chicago and

began recording in 1927. By 1933, he was Bing Crosby's accompanist and established as one of the brightest of the young pianists influenced by Earl Hines, James P. Johnson and Fats Waller. He in turn influenced Wellstood, who had cards printed that read, "Perhaps you can help me to meet Joe Sullivan. My name is Dick Wellstood." He distributed the cards in musicians' hangouts. Finally, the cornetist Muggsy Spanier told Wellstood where Sullivan lived. According to clarinetist Kenny Davern's account of the meeting, quoted in Edward N. Meyer's Giant Strides: The Legacy of Dick Wellstood, the pianist knocked on Sullivan's apartment door well after midnight.

began recording in 1927. By 1933, he was Bing Crosby's accompanist and established as one of the brightest of the young pianists influenced by Earl Hines, James P. Johnson and Fats Waller. He in turn influenced Wellstood, who had cards printed that read, "Perhaps you can help me to meet Joe Sullivan. My name is Dick Wellstood." He distributed the cards in musicians' hangouts. Finally, the cornetist Muggsy Spanier told Wellstood where Sullivan lived. According to clarinetist Kenny Davern's account of the meeting, quoted in Edward N. Meyer's Giant Strides: The Legacy of Dick Wellstood, the pianist knocked on Sullivan's apartment door well after midnight.

Soon this disheveled figure in slippers and a bathrobe comes shuffling through. Joe opens the door and says, "Yeah?" Dick says, "Hi, my name is Dick Wellstood and Muggsy Spanier said to say hello." And Joe Sullivan said, "Tell Muggsy Spanier to go f___ himself," and slammed the door right in Dick's face.

Nonetheless, Wellstood remained a steadfast admirer of Sullivan. Here is one reason, Sullivan's 1933 recording of "Gin Mill Blues."

There is little video of Wellstood performing, but this clip from a concert in Germany in 1982, five years before he died, catches him in full stride, concentration and swing.

New: Torben Waldorff, Afterburn (ArtistShare). The Danish guitarist accomodates his early rock leanings to absorption with expansive jazz of the kind that thrives in downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn and is spreading around the world. Waldorff, tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin and pianist-organist Sam Yahel are leaders among the articulate standard bearers of the movement. They play off one another with fiery inventiveness and with grace that allows the music to breathe. Bassist Matt Clohesy and drummer Jon Wikan are fully immersed in the new sensibility. All of the compositions but one are by Waldorff. The one is Maria Schneider's "Choro Dancado," first recorded on her Concert in the Garden CD. The curve of its Brazilian melodic shape and the elegance of its harmonies inspire a superb performance. Waldorff's chromaticized "Skyliner" (unrelated to the old Charlie Barnet piece) is another high point.

New: Torben Waldorff, Afterburn (ArtistShare). The Danish guitarist accomodates his early rock leanings to absorption with expansive jazz of the kind that thrives in downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn and is spreading around the world. Waldorff, tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin and pianist-organist Sam Yahel are leaders among the articulate standard bearers of the movement. They play off one another with fiery inventiveness and with grace that allows the music to breathe. Bassist Matt Clohesy and drummer Jon Wikan are fully immersed in the new sensibility. All of the compositions but one are by Waldorff. The one is Maria Schneider's "Choro Dancado," first recorded on her Concert in the Garden CD. The curve of its Brazilian melodic shape and the elegance of its harmonies inspire a superb performance. Waldorff's chromaticized "Skyliner" (unrelated to the old Charlie Barnet piece) is another high point.

Old: Art Farmer, Modern Art, UA/Blue Note. This 1958 session paired the trumpeter with

tenor saxophonist Benny Golson in what amounted to a preview of their cooperative band The Jazztet. The pianist was Bill Evans in a brilliant sideman appearance before he left Miles Davis and formed his own trio. Art's twin brother Addison was the bassist, Dave Bailey the drummer. Farmer and Golson had a nearly symbiotic relationship, but it was Evans who inspired Farmer to some of his best playing on record. The pianist's own solos on "The Touch of Your Lips" and "Like Someone in Love" are masterpieces. The young, developing, McCoy Tyner was the pianist when Golson and Farmer launched The Jazztet in 1959. This CD tantalizes the listener with intimations of the glories that might have flowered in that group if Evans had been aboard. It is one of the most satisfying recordings of the l950s.

tenor saxophonist Benny Golson in what amounted to a preview of their cooperative band The Jazztet. The pianist was Bill Evans in a brilliant sideman appearance before he left Miles Davis and formed his own trio. Art's twin brother Addison was the bassist, Dave Bailey the drummer. Farmer and Golson had a nearly symbiotic relationship, but it was Evans who inspired Farmer to some of his best playing on record. The pianist's own solos on "The Touch of Your Lips" and "Like Someone in Love" are masterpieces. The young, developing, McCoy Tyner was the pianist when Golson and Farmer launched The Jazztet in 1959. This CD tantalizes the listener with intimations of the glories that might have flowered in that group if Evans had been aboard. It is one of the most satisfying recordings of the l950s.

In his JazzWax, Marc Myers has a fascinating four-part interview with Bill Holman. I'm no enthusiast of transcribed verbatim interviews, but Myers's introductions, questions and production values make the format work, and in the great arranger he has a subject whose articulateness and wit carry the reader along. Two excerpts:

To read the four parts in order, go to JazzWax and scroll down to July 29. Start with part 1 and scroll back up through parts 2, 3, 4 and an addendum.

I used to think that writing a jazz arrangement was like stream of consciousness, the same as a jazz solo. You just started playing and built on what you just played. Then you go on to the next thing and never repeat yourself. After a few years it finally dawned on me that the ear wants to hear something it recognizes, so I started concentrating on the shape of an entire piece, the form, and how it builds to a climax. As a writer, you also want to avoid getting to the climax too soon. If you do, you'll kill yourself trying to top it in the arrangement. And the result is monotony.

Writing music and arranging never gets easy. I've had students ask me, "How long does it take before it gets easy?" I tell them, "Never." As soon as you get to one point in your development, you're looking at the next level.

Long before he won the Thelonious Monk Institute Composers Competition in 2000, Michael Weiss established himself as a pianist. Fresh out of Dallas in his early twenties, he was soon working with Jon Hendricks, Junior Cook, Charles McPherson and Lou Donaldson, among others. He went on to play with Art Farmer, George Coleman, Frank Wess, Slide Hampton, and the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra. Following his Village Vanguard debut as a leader in 2006, The New York Times noted that Weiss was "a confident and sparkling presence on piano," exhibiting "sensitivity and logic, along with crisp control."

Reminiscing About Johnny Griffin

by Michael Weiss

To hear Michael Weiss in two of his many collaborations with Griffin,Johnny Griffin was one of the great personalities and individuals of jazz, and if jazz is supposed to embody anything, it is individuality, together with improvisation and collaboration. Griffin was one of the very best soloists who could fully express their personality through their instrument. You hear one note and you know that it's Johnny. Everything that came out of his horn was a magnification of who he is. You don't even notice his influences anymore. He really played like nobody else. His phrases were so unpredictable. He had this way of abruptly lunging at things at any moment, but could also finish the same line with a sweet lyrical melody. Griffin should be remembered not only for his technical virtuosity but for how he used that technique in his overall expression, woven into the fabric of his style.

Long before I played with Johnny I knew all his records with Monk and Jaws very well and had even transcribed a few of his solos. In 1985 I had been working with his drummer Kenny Washington so when Griff's regular pianist was unable to make a gig, Kenny recommended me and I joined the band shortly after that. We toured every year up to 2001.

Working with Griffin was among the most - if not the most - exhilarating and electrifying experiences I've had on the bandstand with any leader. And not just because Johnny liked to play fast tempos. At any tempo there was a level of energy and excitement on the stage that never felt commonplace. Even after I worked hundreds of gigs with Johnny over several years, there was an intensity, focus and energy with each set that was unlike any other group I've played with. It was like mental weightlifting. Griffin, a real extrovert, had a lot to express through his horn and was such a commanding presence that he drew the same thing out of you. Having to solo after him night after night I was compelled to make sure my musical statement was meaningful and worthwhile. Accompanying him was also no easy task, but it didn't take long to realize the best modus operandi was to just stay out of his way. Overall, it was a great training ground to experience that level of seriousness of purpose and integrity on the bandstand.

Griff was fun to be around. He knew how to enjoy life and seemed very comfortable in his own skin. This generally happy demeanor was quite contagious. On the gig, he listened closely to the rhythm section as we worked our stuff out in our solos. He especially delighted in listening to us wrestle through a particular musical idea. During such occasions, I might look up and see Johnny with his eyes aglow and a big smile. He enjoyed the creative struggle and he was along with you for the ride. Playing jazz for him was a positive, joyous experience and he spread that feeling to everyone in the audience. He had the people in the palm of his hand all the time. He was very comfortable on the mic and frequently said some very funny things. But he was deadly serious about musicmaking - on the bandstand there was no nonsense, no messing around.The Johnny Griffin Quartet was one of the few working bands in jazz that was still touring regularly throughout the 1990s. As performing night after night is the only way a musician can really develop and improve on his craft, I'm grateful to have been able to do exactly that with Johnny Griffin.

listen to the 1990 CD The Cat and to Griffin's 2000 quintet album with Steve Grossman. Grossman, also an expatriate American tenor player in France, is an improviser whose zeal and vigor nearly match Griffin's.

listen to the 1990 CD The Cat and to Griffin's 2000 quintet album with Steve Grossman. Grossman, also an expatriate American tenor player in France, is an improviser whose zeal and vigor nearly match Griffin's.

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary