Most Paul Gauguin exhibitions show him off as a self-described “savage,†that sensualist who abandoned his family in France to canoodle with young Tahitian girls. He did behave badly a lot of the time, even as he was turning out gorgeous paintings.

So it was refreshing to see Gauguin: A Spiritual Journey last year at the de Young museum in San Francisco. The exhibit, a joint venture between Copenhagen’s Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, leaves out his most sensualist works and therefore presses visitors to see other aspects of his work.

Plus, journey was an apt description for a title: the exhibition is a chronological mini-survey of Gauguin’s development as an artist and his search for an understanding of his own and others’ spirituality.

As I wrote in my review, published in today’s Wall Street Journal, you can see Gauguin work on his artistry in these paintings, drawings, ceramics and wood carvings. He pays homage to artists who inspired him (such as Pissarro, Manet, Delacroix and Degas) early on, and then in Brittany and on the South Sea islands, he turns into the Gauguin we know and love.

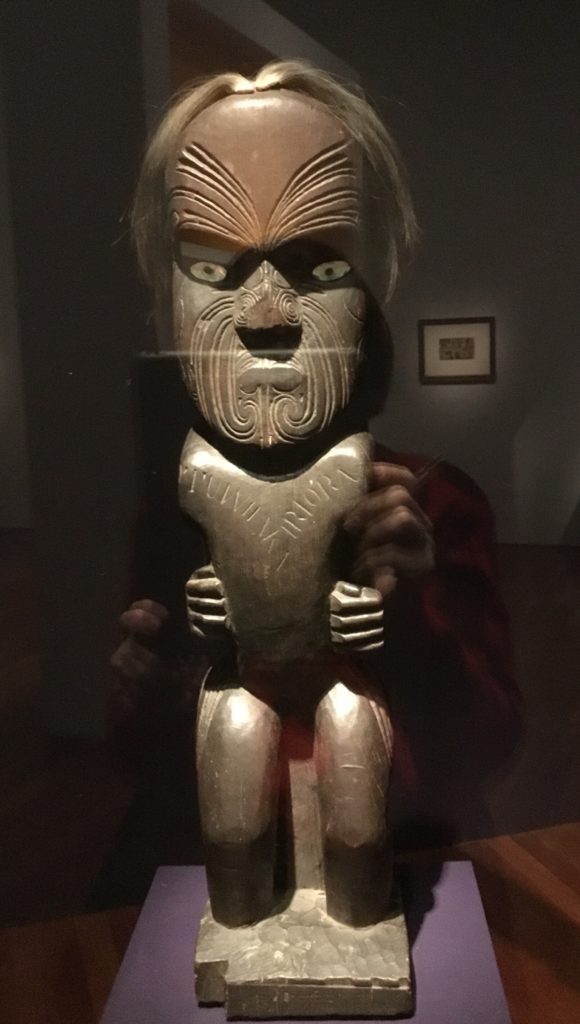

The less usual aspect for visitors is that, almost from the beginning, according to curator Christina Hellmich of the de Young, Gauguin inserts hints of his spiritual quest. Later, when he gets to the South Seas, he is looking at native rituals. totems and other objects while he thinks about his paintings. Several Oceanic objects are on view: instead of seeing Gauguin as we usually do, in the context of his European peers, visitors to the de Young see him a different context altogether.

It fact, though Met director Max Hollein departed the San Francisco museums last June, he deserves much credit for this exhibition. As his curators (not him) told me, a courier from the Glyptotek–which owns many Gauguin works, a legacy of his wife, who was Danish–had brought something to SF some time back. Hollein asked her if there was anything she’d been thinking about, anything she’d like to do. Her response: she’d like to put Gauguin’s work in the context of Oceanic art.

Bingo, Hollein said (metaphorically speaking): the FAMSF had just the right collection; it also owns several Gauguin drawings. Thus the partnership.

But that was not the end of things. Then he made another smart move: rather than assign the exhibit to the European paintings department, he selected Christina Hellmich, curator of the museum’s Oceanic art department, as the organizer. She brought fresh eyes to Gauguin. I know because I spoke with her for about an hour, and learned a lot. I may or may not agree with all of it, but it was very interesting.

Here’s an example. In one of the last paintings in the exhibition, Gauguin’s Flowers and Cats, she pointed out the cat on the right’s eyes. She sees a similarity with the eyes of a 1902 gable figure that Gauguin may have seen. At the least, he saw items like it.

A stretch? Maybe, maybe not.

Photo Credits: Top two, courtesy of the FAMSF; bottom, JHD