In London a few weeks back, I was fortunate to be there on the day of the press preview for Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy at the Tate Modern. You might think. at first, that doing a Picasso show is easy–few artists have better name recognition and for a long time, Picasso was like gold, Impressionism and Egypt, a guaranteed box office success. Lately, though, he feels overexposed–not just at exhibitions but also at auction.

In London a few weeks back, I was fortunate to be there on the day of the press preview for Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy at the Tate Modern. You might think. at first, that doing a Picasso show is easy–few artists have better name recognition and for a long time, Picasso was like gold, Impressionism and Egypt, a guaranteed box office success. Lately, though, he feels overexposed–not just at exhibitions but also at auction.

And this was the Tate Modern’s first ever solo Picasso exhibit; Frances Morris, the director, wanted to get it right. She and the curators surely did, along with their colleagues at the Musee Picasso in Paris, which co-organized the show.

1932 was a critical year for Picasso–his “year of wonders,” one in which he created some of his best works, made works for and organized (full control!) a major retrospective exhibition at the Galeries Georges Petit, in Paris, scheduled for June of 1932, and led a dichotomous personal life, bouncing between his wife Olga and his mistress Marie-Therese Walter. He revealed the existence of the latter in his paintings for the first time (five years into their affair) in 1932. He was 50.

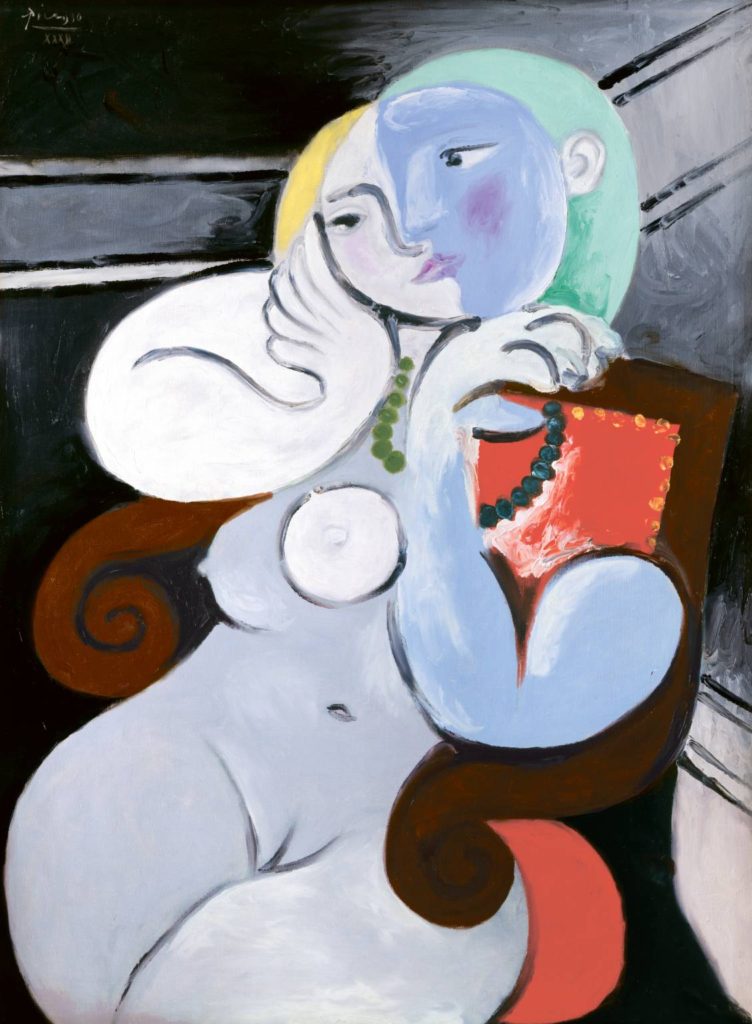

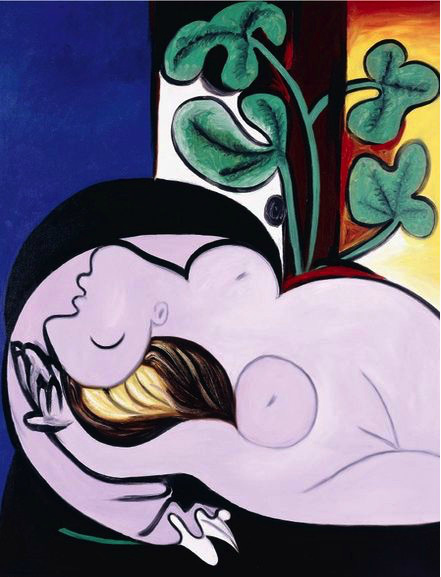

What struck me as I moved through the many galleries was the vast, repeated and fast-paced creativity he exhibited. This is especially evident in the fourth gallery, “Early March.” There on the walls are three of his very best paintings–two were executed, or finished, on consecutive days. On Mar. 8, he painted Nude, Green Leaves and a Bust (top) and on Mar. 9, he made Nude in a Black Armchair (middle). That was a Wednesday: the following Monday, Mar. 14, he completed Girl Before a Mirror (third from top). Before long, Alfred Barr had it in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, a gift of Mrs. Simon Guggenheim.

What struck me as I moved through the many galleries was the vast, repeated and fast-paced creativity he exhibited. This is especially evident in the fourth gallery, “Early March.” There on the walls are three of his very best paintings–two were executed, or finished, on consecutive days. On Mar. 8, he painted Nude, Green Leaves and a Bust (top) and on Mar. 9, he made Nude in a Black Armchair (middle). That was a Wednesday: the following Monday, Mar. 14, he completed Girl Before a Mirror (third from top). Before long, Alfred Barr had it in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, a gift of Mrs. Simon Guggenheim.

In the same room are three other works he created along with them, all within 12 days: Still Life with Tulips; Still Life: Bust, Cups and Palette; and The Mirror. Of these six paintings, four are in private collections–so this is an extraordinary moment to see what Picasso could do, probably not to be experienced again any time soon!

He had accomplished as much, but not (for me) to such great effect, in January, when he painted Rest on Jan. 22; Sleep on Jan. 23 and The Dream on Jan. 24. That month, he focused on portraits of a woman–Marie-Therese, mostly–in an arm chair. She is, the curators said, imagined–because Picasso rarely painted from life, and the mood changes quite a bit, from sensuous to surrealist depictions.

He had accomplished as much, but not (for me) to such great effect, in January, when he painted Rest on Jan. 22; Sleep on Jan. 23 and The Dream on Jan. 24. That month, he focused on portraits of a woman–Marie-Therese, mostly–in an arm chair. She is, the curators said, imagined–because Picasso rarely painted from life, and the mood changes quite a bit, from sensuous to surrealist depictions.

Those three January works show, in the words of one of the curators, Achim Borchardt-Hume, Picasso’s relationships with women, whom he found “irritating, interesting and the perfect dream.”

It was an ambitious year, to say the least. And varied. One point, Borchardt-Hume said, is that he was mixing styles and saying, in doing that, this is my work and it’s still all relevant. At this point, art historians were categorizing his work into his blue, rose, cubist periods etc. Picasso didn’t like that.

As the year progressed, politics and economics were getting increasingly darker and so was Picasso’s mood. After the retrospective opened, Picasso worked more quickly on, mostly, smaller works–with one exception, Nude Woman in a Red Armchair, which the Tate purchased in 1953 (below). He made many drawings and beach scenes, but by the fall he was focused on the subject of the Crucifixion. Inspired by the Eisenheim altarpiece at Colmar, he made surrealist interpretations of the subject.

Picasso finished out the year with more dark subject matter, with more gray in his works and places where his color does not conform to his line.

It was an amazing year. The Tate Modern and the Musee Picasso have done very well with it, pulling together what Borchardt-Hume confirmed to me was the “vast majority” of the paintings Picasso made that year. An extraordinary number–about 40 works–came from 25 private lenders.

The exhibition contains much more than I have described here, including a lovely salon hang of family portraits that he created for his retrospective (below).

And here are a few links to reviews, each of which has different pictures you may want to see.

The Guardian, also The Guardian and The Evening Standard.

If you can get to London to see this exhibit, which runs until Sept. 9, I recommend it.