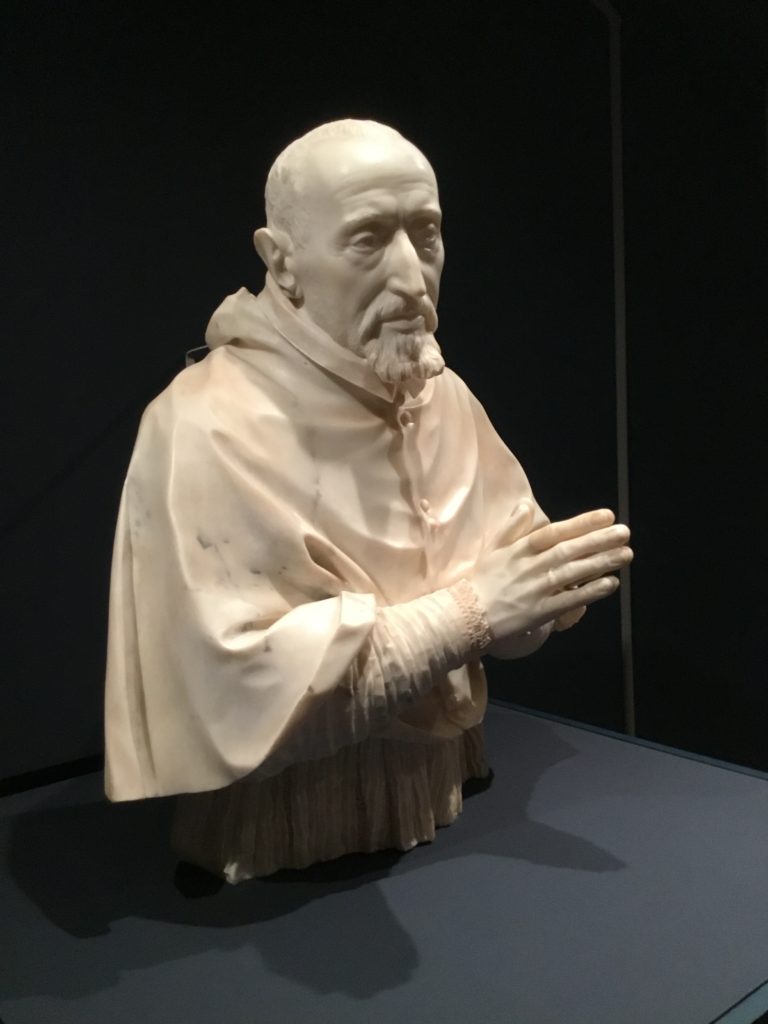

As great projects often do, the amazing exhibition on view at the Fairfield University Art Museum began with an impossible dream. Seeking ideas for a show to mark the university’s 75th anniversary this year, museum director Linda Wolk-Simon convened an exhibition committee, among show members was Xavier Salomon, chief curator at the Frick Collection. Salomon suggested that she ask to borrow Bernini’s great marble bust of Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino—which normally resides in the Gesu, the Jesuit’s mother church, in Rome.

As great projects often do, the amazing exhibition on view at the Fairfield University Art Museum began with an impossible dream. Seeking ideas for a show to mark the university’s 75th anniversary this year, museum director Linda Wolk-Simon convened an exhibition committee, among show members was Xavier Salomon, chief curator at the Frick Collection. Salomon suggested that she ask to borrow Bernini’s great marble bust of Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino—which normally resides in the Gesu, the Jesuit’s mother church, in Rome.

The Fairfield museum is located in Bellarmine Hall, after all, and he is the university’s patron saint.

Wolk-Simon thought, they’ll say no—but why not? The bust, created in 1621-24, had never before left Rome. Bernini (1598-1680) was quite young when he carved it.

She was right. The church say no–the first time. She also asked to borrow other things, too, and eventually the church came around and granted four of her requests–and then the rector inquired why she had not requested his favorite item, the bejeweled silver-and-gilt-bronze Cartegloria of Saint Ignatius made by Johann Adolf Gaap in 1699 (detail, right).

And that’s how the museum came to host an international loan exhibition, Art of the Gesù: Bernini and his Age, of nearly 60 objects from museums including the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Met, the Princeton University Art Museum, and many more. It opened on Feb. 2 and runs until May 19.

I’ll get back to the show in a minute. But perhaps even more important will be the catalogue for “The Holy Name–Art of the Gesu: Bernini and HIs Age.” It will be a 600-page monster with essays by many scholars and a foreward by Philippe de Montebello, the Director Emeritus of the Met who served as honorary chair of the exhibition committee. For the exhibit’s press release, he said, “If I were still Director of the Metropolitan, I would be jealous of Fairfield doing this show. It’s simply incredible–it brings to the Fairfield University Art Museum some of the greatest artists working in 17th century Rome.”

I’ll get back to the show in a minute. But perhaps even more important will be the catalogue for “The Holy Name–Art of the Gesu: Bernini and HIs Age.” It will be a 600-page monster with essays by many scholars and a foreward by Philippe de Montebello, the Director Emeritus of the Met who served as honorary chair of the exhibition committee. For the exhibit’s press release, he said, “If I were still Director of the Metropolitan, I would be jealous of Fairfield doing this show. It’s simply incredible–it brings to the Fairfield University Art Museum some of the greatest artists working in 17th century Rome.”

For me, it also fulfills another purpose. The Gesu, with its rather plain exterior (click on the link in my first paragraph to see both exterior and interior photographs), sits in a crowded part of Rome; it is easy to overlook. Yet inside, it’s stunning. The ceiling of the apse is a fresco–Glory of the Mystical Lamb–painted by Giovanni Battista Gaulli. And that’s just the start. The curious can find much more about it online.

From the church, Fairfield was able to borrow Gaulli’s final painted wooden model for the apse fresco, plus a gilt bronze statue of Saint Teresa of Avila by Ciro Ferri, the bust, the cartegloria and another true treasure–a silk chasuble embroidered with gold, silver and silk threads, c. 1575-1589 (detail, left), worn by the church’s great benefactor, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. .

From the church, Fairfield was able to borrow Gaulli’s final painted wooden model for the apse fresco, plus a gilt bronze statue of Saint Teresa of Avila by Ciro Ferri, the bust, the cartegloria and another true treasure–a silk chasuble embroidered with gold, silver and silk threads, c. 1575-1589 (detail, left), worn by the church’s great benefactor, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. .

The Bellarmine-Bernini bust, which normally hangs high in the church but here can be seen at eye level, is gathering most of the attention in the art world. On Instagram, Luke Syson, chairman of the Met’s European Sculpture and Decorative Arts department, wrote, in part:

Today I witnessed an object I’d previously categorized as a work of baroque art–a very great one but nonetheless the rather remote portrait of a long-dead individual with a history of religious learning and obduracy–spiritually recharged to become the animate patron saint of this Jesuit university. It’s partly that the sculpture is normally an ingredient of the minestrone of Counter-reformation glory that is the Gesù, placed high up, impressive but rather invisible, just one of Rome’s many treasures. At Fairfield, it’s not just that one can see him properly for the first time, though that’s absolutely marvelous. It’s also, and more importantly, that he could only have traveled there–the Jesuit authorities would never have supported a loan to somewhere else and requests to borrow the piece by larger, grander, older museums have always been turned down. They were right. Here he’s turned into the living Saint Robert Bellarmine rather than the long-dead seventeenth-century cleric known for having put a spoke in Galileo’s scientific wheel….

Bernini makes him embody a combination of deep thought and profound belief. His fingers scintillate in prayer. The fierce muscles above his eyebrows express his brain power. It’s an extraordinary piece of characterization. Bernini did something amazing but, fascinatingly and most unexpectedly, it’s only at Fairfield that the Saint has come truly alive for me.

I can’t end this without posting a painting–so here, below, is Gaulli’s The Vision of St. Ignatius at La Storta (c. 1685-90)–Ignatius being a founder of the Jesuits.

So–go if you can. Visit the Gesu next time you are in Rome. Meantime, enjoy the photos I took while there.