Yayoi Kusama is one of those artists whose work is easy to love. Although she made it (or much of it) as therapy for herself–beset from early on with mental health issues and thoughts of suicide–her works come across to viewers as exuberant and bedazzling. And in many cases, fun–even as they are thought-provoking.

Yayoi Kusama is one of those artists whose work is easy to love. Although she made it (or much of it) as therapy for herself–beset from early on with mental health issues and thoughts of suicide–her works come across to viewers as exuberant and bedazzling. And in many cases, fun–even as they are thought-provoking.

Last week, I was lucky enough to arrive in Seattle (on an unrelated business trip) just as her show at the Seattle Art Museum, Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, was about to open. I got a press preview, which means that the galleries were mostly empty when I was there. That’ll be in distinct contrast to the experiences of many: advance ticket sales for the exhibit are completely sold out, despite the steep cost of $34.95. A limited number of tickets are available now only on a first-come, first-served daily basis. And the museum has added Sunday night tickets for members only.

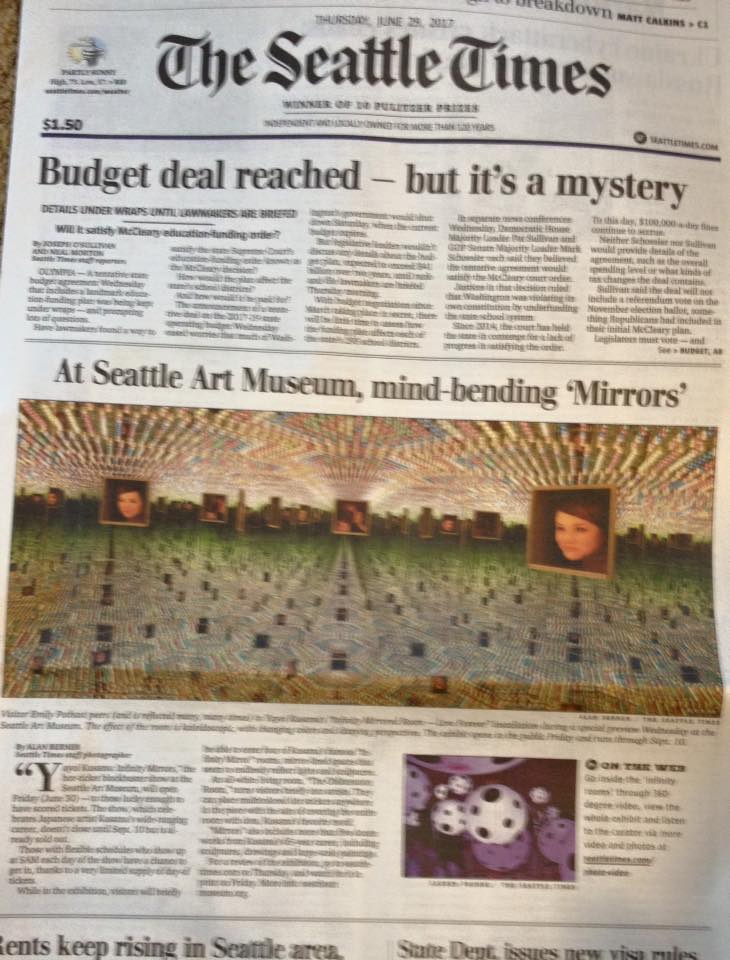

This exhibit was organized and appeared first at the Hirshhorn Museum and focuses, at Kusama’s request, on her mirrored rooms, according to the Seattle Times review. (The Times also made the show front page news on the day before the review (at right), for which all art-lovers must be grateful.)

This exhibit was organized and appeared first at the Hirshhorn Museum and focuses, at Kusama’s request, on her mirrored rooms, according to the Seattle Times review. (The Times also made the show front page news on the day before the review (at right), for which all art-lovers must be grateful.)

These rooms are important to her. Here’s an explanation from WSJ. Magazine:

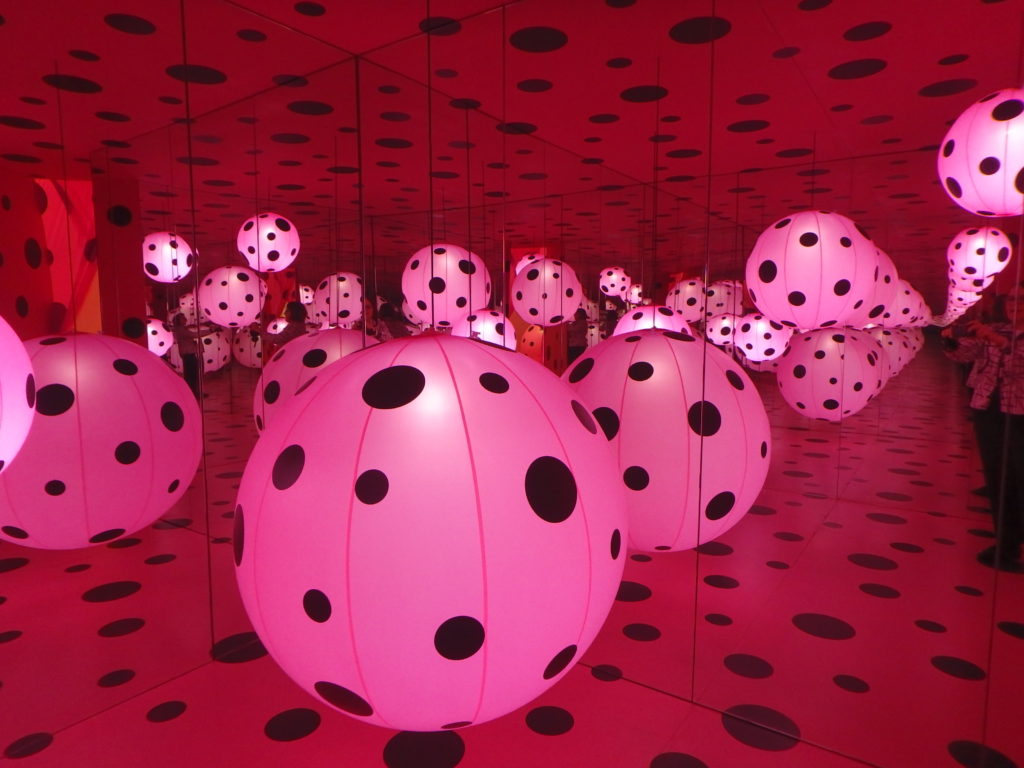

Kusama conceived of these installations in part as an opportunity to savor the supreme vanity of regarding one’s likeness reflected endlessly.

“I’ve always been interested in the mystique that a mirrored surface presents,†says Kusama. “In my mirror rooms, you see yourself as an individual reflected in an expansive space. But they also give you the sensation of cloistering yourself in another world.â€Â Often lit up by myriad multicolored LED lights (earlier iterations of the rooms from the ’60s were simpler affairs, filled with polka-dot patterns and phallic, tuberlike soft sculptures), the rooms are meant to evoke a cosmic feeling of being an individual within a multitude—as planet Earth is “like one little polka dot, among millions of other celestial bodies.â€

Still, as the Seattle review noted,

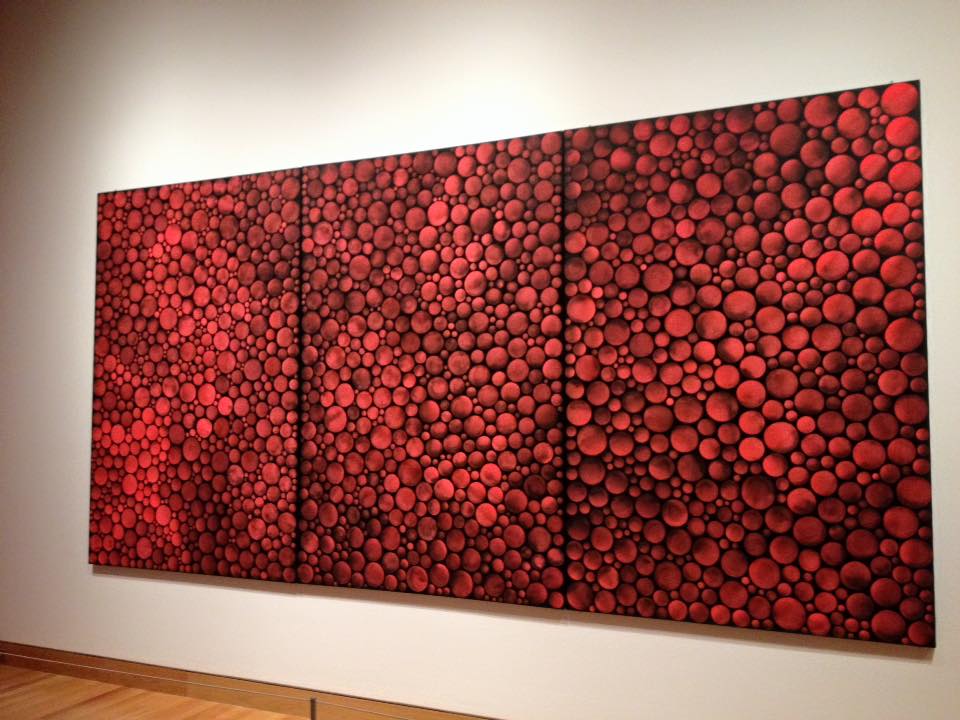

There are [also] surrealistic paintings from the 1950s, soft sculptures from the 1960s, Joseph Cornell-inspired collages from the 1970s, very recent work, and documentary photos and ephemera, all of which gloriously establish Kusama’s unique place in contemporary art history.

Agreed, and I loved it all! I had not seen her watercolors and gouaches before, and they are intriguing. (I’d post one, but the only one I took did not come out clearly enough to be useful as an illustration.)

Seattle is trying hard to prevent any incidents of damage, as happened at the Hirshhorn, when a pumpkin was broken by someone taking a selfie in the room called “All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins†(above left). At SAM, visitors enter that room along with a staff member. This will slow things down, adding to the waits at the rooms, but it’s necessary.

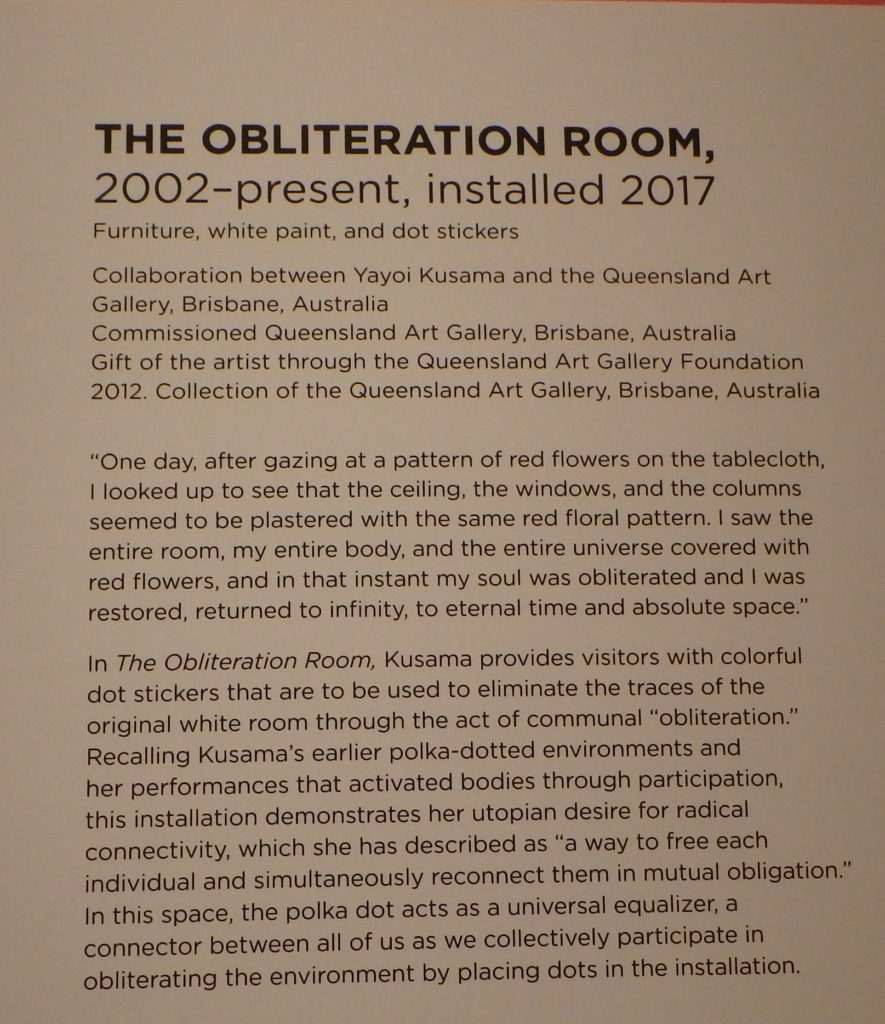

One aspect has gotten less attention than I would have expected, given today’s emphasis on participatory art. Near the end of the Seattle show, there’s an “obliteration room.” It began as an all-white room, filled with furniture, and each visitor is given polka-dot stickers to place anywhere in the room–floor, walls,  goblets on the dining table, etc. (label at right). Again, quoting the Seattle Times,

goblets on the dining table, etc. (label at right). Again, quoting the Seattle Times,

Kusama has said that her repetitive processes — covering everything with dots or sewing hundreds of fabric forms, for example — are acts of “self-obliteration.†She has described her labor-intensive methods as “art-medicine.â€

I disagree, strenuously, with those who cannot consider this art, who think it is art for children, who say it lacks meaning, who say it is mere spectacle. Several pieces are, for me, quite eloquent. Maybe a trying a little harder to understand Kusama’s art is in order. Art can be enjoyed and consumed on many levels, and sometimes its impact is not clear until long after one leaves an exhibition.