It would be a good idea. As the FBI recently warned, speaking about the case of Michigan art dealer Eric Spoutz, who pumped at least 40 forgeries into the market over the past 10 years (h/t to ArtNet) (to learn to spot fakes, that is):

It would be a good idea. As the FBI recently warned, speaking about the case of Michigan art dealer Eric Spoutz, who pumped at least 40 forgeries into the market over the past 10 years (h/t to ArtNet) (to learn to spot fakes, that is):

Although Spoutz has been sentenced, [agents] McKeogh and Savona do not believe they have seen the last of the fakes he peddled. …there could be hundreds more that were sold to unsuspecting victims. “This is a case we’re going to be dealing with for years. Spoutz was a mill,†McKeogh said.

So the exhibition that Winterthur recently unveiled, Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes, comes at an opportune time. It presents more than 40 fakes or forgeries–fine art, couture, silver, sporting memorabilia, wine, musical instruments, antiquities, stamps, ceramics, furniture, and folk art–drawn from its permanent collection and public and private collections. Conservationists from Winterthur and other institutions have used scientific analysis and connoisseurship to expose these fakes: their analysis and the pertinent stylistic clues is presented alongside the objects to show the techniques used by forgers to try to fool experts and/or trusting collectors. Among the items on display is a Rothko painting that Glafira Rosales, the notorious Long Island art dealer, sold to the Knoedler Gallery.

I have not seen the exhibit–I’ve just read about it. But such shows–other museums have done this in the past–are always, in my experience, learning experiences. And in keeping with today’s trend to involve visitors, Winterthur’s show invites visitors “to investigate several unresolved examples and share their opinion about the authenticity of the object based on the available evidence.” The highlights in this, the final section, include:

I have not seen the exhibit–I’ve just read about it. But such shows–other museums have done this in the past–are always, in my experience, learning experiences. And in keeping with today’s trend to involve visitors, Winterthur’s show invites visitors “to investigate several unresolved examples and share their opinion about the authenticity of the object based on the available evidence.” The highlights in this, the final section, include:

- A painting purported to be by master forger Elmyr de Hory (whose fakes have themselves become highly collectible).

- A oil painting whose owner has been trying for many years to prove it a genuine work by Winslow Homer.

- A vampire killing kit brought to Winterthur for authentication by the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

Colette Loll, Â the founder of Art Fraud Insights, LLC, a Washington, DC, based consultancy, co-curated the exhibition with Winterthur’s Linda Eaton, a textile conservator who also serves as the museum’s director of collections.

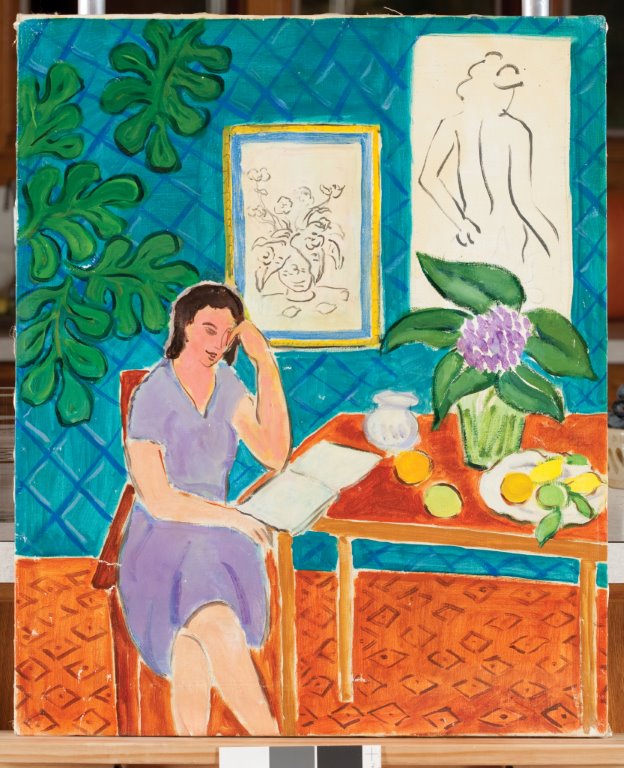

Pictured here (top) is a painting “believed to be by de Kooning” from a private collection. Here’s what the label says:

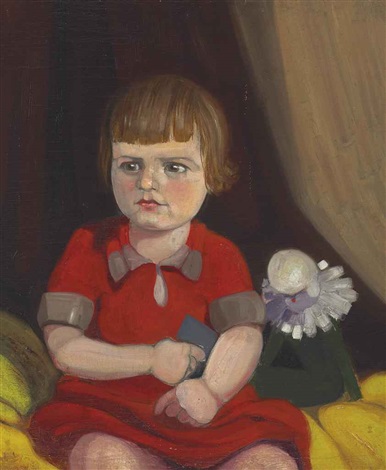

Discovered online and purchased for just 450 euros, this portrait of a young boy holding a ball is stylistically similar to Portrait of Renée [at right]. The children share the same haunting expression, posture, and awkward clutching of an object. The works are the same dimension and also share the same technique, with thick paint on the skin; the same use of shadows; traces of conté crayon; and the same lips, hairstyle, and eyebrows. This work was sold with no provenance; the seller simply claimed that it once belonged to a homeless man who wished him to dispose of his things.

And here is the de Hory, mentioned above.

What do you think of these?

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Winterthur (top)