Life is constricted, to some extent, for all single-artist museums–and more than most at the Clyfford Still Museum. As decreed by the artist, it can never exhibit works by any other artist and it can’t have a restaurant or auditorium, among other things. Yet almost about three years ago, in November, 2011, it opened in Denver.

Life is constricted, to some extent, for all single-artist museums–and more than most at the Clyfford Still Museum. As decreed by the artist, it can never exhibit works by any other artist and it can’t have a restaurant or auditorium, among other things. Yet almost about three years ago, in November, 2011, it opened in Denver.

When I received a press release a while back announcing its tenth special exhibition, opening this coming Friday–The War Begins: Clyfford Still’s Paths to Abstraction–I thought it was time to check in and see how it is doing. The answer is pretty well, thanks.

As I report for an article published yesterday on The Art Newspaper website:

…the museum has received 38,562 visitors in 2014—already close to the 40,000 the museum originally projected for an entire year and likely to surpass last year’s total of 42,685. In 2012, its first full year, the museum attracted 61,204 visitors.

More impressive, to me, are those 10 shows, all but one curated by director Dean Sobel, consulting curator David Anfam, or the two of them together. The lone exception was organized by the chief conservator,  James Squires. They include, aside from two inaugural survey exhibitions:

…“Vincent/Clyffordâ€, featuring paintings and works on paper created during Still’s early years, when his subjects and palette echoed van Gogh’s (timed to coincide with the Denver Art Museum’s “Becoming van Goghâ€; “Memory, Myth & Magicâ€, which exhibited Still’s works that allude to ancient cultures, artistic traditions and his memories; “The Art of Conservation: Understanding Clyfford Stillâ€, which explained Still’s materials and working methods plus the ways conservators are striving to preserve his works; and “1959: The Albright-Knox Art Gallery Exhibition Recreatedâ€, which mimicked one of the few museum exhibitions of his work in his lifetime.

More details at the above link, including some of Sobel’s plans for next year. He has plenty to work, as about half of the 825 paintings the museum owns haven’t yet been unrolled since their shipment from art storage in Maryland. And very few people are familiar with Still’s drawings–many didn’t even know they existed–which number about 2,350.

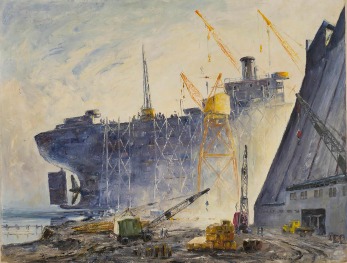

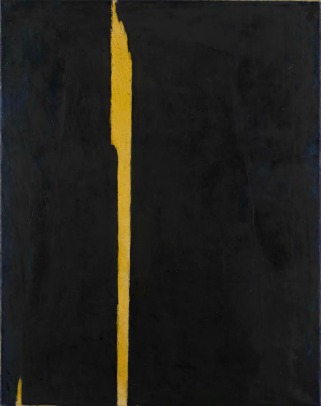

The exhibit opening Friday, the museum said in a press release, “highlights the previously unknown dialogue between Still’s work in war industries and his early breakthrough into abstraction.†I’ve provided two paintings from it here (both from 1942), and here’s the museum’s web description.

The exhibit opening Friday, the museum said in a press release, “highlights the previously unknown dialogue between Still’s work in war industries and his early breakthrough into abstraction.†I’ve provided two paintings from it here (both from 1942), and here’s the museum’s web description.

In fact, because Still’s work remains largely unknown, Sobel has had to change tactics for his special shows: He had learned that he shouldn’t clear out all nine of the museum’s galleries, but rather that special shows are best implanted in the chronology the museum presents. Visitors want to learn Still’s narrative.

The permanent collection narrative changes anyway: in a rotation that starts this month, 53 works on paper will be hung, 40 of which have never been exhibited publicly.

If there has been a disappointment, Sobel says, it’s the lack of national critical review, except perhaps for its opening. Granted, not many critics are traveling beyond the coasts  very often, but it would be great if they weighed in on these special exhibits. As for the museum world, Sobel said, “a lot of my colleagues have only been visiting recently.”

His neighbor, director Christoph Heinrich of the Denver Art Museum, says the Still museum is “part of the conversation here in town,” and not least because of the special exhibits. But also, he said, because “it’s an incredibly in-depth look at the work of one really influential artist. Every artist knew him, but the public didn’t because he exerted so much control.”

Photo Credits: © City and County of Denver