So far, The World Is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cézanne, a “ground-breaking” special exhibition at the Barnes Foundation, has been getting good reviews. The Wall Street  Journal‘s review called it “small but select” and concluded:

Journal‘s review called it “small but select” and concluded:

Although it offers only a taste of the bountiful feast Cézanne’s paintings as a whole at the Barnes provide, “The World Is an Apple” allows one to scrutinize the artist’s still lifes in illuminating isolation from the work of his peers, and to appreciate how the artist’s powerful, painterly sensations could trump even the most traditional subjects he depicted. After viewing the exhibition, Cézanne’s inimitable touch and tenacious presence in all of his art at the Barnes becomes even more apparent, and his pre-eminence as a modern painter undeniable. Somewhere, the curmudgeonly collector is smiling.

Meanwhile, The New Criterion said:

Cézanne’s depictions of simple objects are novel in their focus on materiality, giving the intensely modelled subjects a subtle power: they were nothing short of Cézanne’s manifesto on painting itself.

I haven’t yet traveled to Philadelphia to see it, but hope to before it closes on Sept. 22 (before moving to the Art Gallery of Hamilton, in Ontario, Canada, beginning Nov. 1).

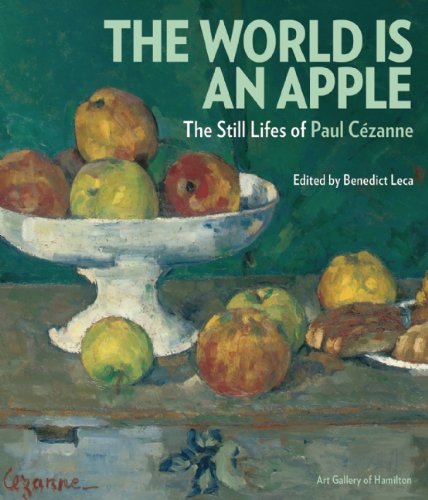

However, I do have a copy of the catalogue, a beautiful tome edited by Benedict Leca, the show’s key curator, now Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Hamilton gallery (previously at the Cincinnati Art Museum). Rather than review it here, I decided to ask Leca a couple of questions and print his responses.

What’s the one takeaway you want people to have after they peruse the catalogue?

Contrary to received views of still life as literally dead (nature morte), as the traditional “silent life†of objects that are inert and devoid of meaning save for the symbolic (as per the 17c Dutch still life tradition, for example), Cezanne’s still lifes—in their bright coloring, dynamic surfaces, distorted spaces and allusive juxtapositions–present objects that mean differently than what has traditionally been assigned to them as still life objects in the art historical record.

My essay argues for Cezanne’s highly personal, subjective mobilization of still life—for his own self-definition—this in a genre that has historically been conceived in terms of an absence of a human subject. Paul Smith’s essay shows us that far from the flatly symbolic or indeed purely material interpretations, Cezanne used his still life as vehicles for highly scientific color experimentation that sought to account for the contingencies of vision, that is, of motion and mobile colors—specifically through things that have historically been conceived as static and inert.

In short, Cezanne explodes the narrow range of meaning given to still lifes and their objects. The book—and I say this humbly—offers the most sustained discussion of Cezanne’s still life anywhere, and both supports the exhibition and offers alternative, in depth reading.

Would people who go to the exhibit get the same message?

I would hope that any lay viewer would register Cezanne’s oddness (in his still lifes), that something is amiss, and that he or she would in turn intuit that these pictures depart from the “silent life†of things. The didactics (which were a communal effort) emphasize the whimsy, the open pictorial structures, the invitation to imagination that trespasses beyond the traditional, more-or-less fixed symbolic meanings attached to such things as apples and skulls.

Cezanne’s still lifes are at bedrock an invitation to imaginative leaps that would join ours with his. Together, the book and the show demonstrate the many ways one might read Cezanne’s still lifes.

Do you have a favorite Cezanne still life?

Certainly, among the show pictures I would isolate the cover image Apples and Cakes—a rarely seen masterpiece shown at the 3rd Impressionist exhibition of 1877—for its beautiful coloring and dynamically touched surface. One would be mistaken, meanwhile, to not pay particular attention to the famous, late Three Skulls on a Patterned Carpet. Cezanne evidently conceived this picture as a sort of manifesto. Its overloaded surface and the highly suggestive arrangement is a testament to Cezanne’s quest to record and communicate his “sensations,†but also to his contingent painting style, which capitalizes on oddities, visual puns, and plays of forms that arise during the act of painting. Again, in that sense, Cezanne offers us not a world of things, but a world of actions—of movement instead of stasis.

Will the exhibition be the same in Ontario as it is at the Barnes? Installed the same way?

There are indeed a couple of Cezannes that for various reasons were ‘Barnes Only.’

However, the iteration of the show in Hamilton will have two added components missing from the Barnes Foundation presentation: a ‘contextual’ early years section to open the show, and a so-called ‘coda’ section to end it. That is, when Cezanne arrives on the scene in Paris in the early 1860s, he looks at & is influenced by realist, Chardin-infused still lifes that have a considerable impact on his early still life production. I’m talking about dark-toned, rustic kitchen scenes by the likes of Theodule Ribot, Antoine Vollon and Philippe Rousseau.

As it happens, the AGH has a number of outstanding representative examples of just such realist still lifes by these very artists, and so the AGH version of the show will open with a brief ‘backgrounder’ of 4 realist still lifes tightly hung, so that people can glimpse right from the get-go how Cezanne departs from convention and prevailing modes of still life. On the other end—as fully explicated in Joe Rishel’s Cezanne and Beyond exhibition of 2009 in Philadelphia—Cezanne was highly influential for his peers and the next generation of still life painters. Thus the AGH show will close with three still life paintings by artists who looked to Cezanne: van Gogh, Still Life with Ginger Jar (1885), Emile Bernard, Nature Morte a la Tasse (1886)—both from the McMaster University Museum of Art (Hamilton, ON)—and a Georges Braque, Nature Morte (1926) from the AGH collection (we know, for example, that Braque owned a Cezanne apple painting).

—

The catalogue sells for $54.95.