On Tuesday, the Portland Museum of Art opens what will likely be a pride and joy: the 2,200 sq. ft. studio in Prouts Neck, Maine, of Winslow Homer, which it purchased in 2006 from Homer’s great grand-nephew, Charles Homer Willauer. The museum has raised $10.8 million in a national capital campaign to support the acquisition, preservation, interpretation, and endowment of the studio, which it has restored to its appearance during Homer’s lifetime, for $2.8 million.

On Tuesday, the Portland Museum of Art opens what will likely be a pride and joy: the 2,200 sq. ft. studio in Prouts Neck, Maine, of Winslow Homer, which it purchased in 2006 from Homer’s great grand-nephew, Charles Homer Willauer. The museum has raised $10.8 million in a national capital campaign to support the acquisition, preservation, interpretation, and endowment of the studio, which it has restored to its appearance during Homer’s lifetime, for $2.8 million.

In the course of the restoration, the museum learned a lot about Homer: some little, such as that he apparently ate clams and just tossed the shells (they were found under the floorboards along with some paintbrushes);, and some big, such as the fact that, instead of being a recluse, Homer and his family developed the Prouts Neck community using Easthampton as a model. As one catalogue essay says: “It is a rare hermit that who exhibits a flair for real estate, but Winslow and his brother Charles, Jr. were active developers, so much so that by the time of Homer’s death in 1910, six hotels and some sixty private cottages dotted Prouts Neck.â€

The downside to this, if there is one, is that visitation is via a van from the museum to the studio twelve miles away and then by guided tour — just three a day, limited to 10 visitors each, from Sept. 25 through Dec. 2, 2012 and next spring from Apr. 2 through June 14. A bigger downside: they cost $55 each.Â

The downside to this, if there is one, is that visitation is via a van from the museum to the studio twelve miles away and then by guided tour — just three a day, limited to 10 visitors each, from Sept. 25 through Dec. 2, 2012 and next spring from Apr. 2 through June 14. A bigger downside: they cost $55 each.Â

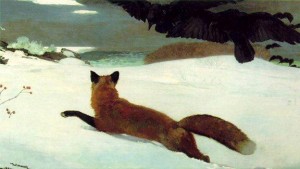

Wisely, in planning this, the museum has gone beyond the studio, where Homer made some of his most iconic works. The Portland museum will be showing paintings that he created in that studio. Weatherbeaten: Winslow Homer and Maine, which runs through Dec. 30, brings together 38 major oils, watercolors and etchings — many late seascapes — from museums including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Art Institute of Chicago; the Smithsonian American Art Museum; and the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.  For the first time since it was painted there, Homer’s  Fox Hunt (1893) will be in Maine, a rare loan from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

And Portland is putting a contemporary spin on this as well: It has commissioned five artists to photograph the studio using techniques available in Homer’s days, and they will go on view on Oct. 6 in a display called Between Past and Present: The Homer Studio Photographic Project. A few details:

And Portland is putting a contemporary spin on this as well: It has commissioned five artists to photograph the studio using techniques available in Homer’s days, and they will go on view on Oct. 6 in a display called Between Past and Present: The Homer Studio Photographic Project. A few details:

They employed both historic, large-plate cameras and modern digital cameras, and a variety of print processes. The earliest method of making images of the real world with light—the camera obscura—is the technique explored by Abelardo Morell with his unique tent camera. Alan Vlach specializes in salted paper prints, the first form of prints made from negatives, introduced in England in the 1840s. Keliy Anderson-Staley developed her collodion prints outdoors using a portable darkroom at Prouts Neck, much like 19th-century portrait photographers. And the gum bichromate and platinum prints, produced by Brenton Hamilton and Tillman Crane, represent the type of fine art photography most used during Homer’s day.

The Portland museum has a real treasure here, and should make the most of it in a way that’s respectful of the property’s limitations. I suspect it will learn during the coming year, and perhaps make changes after that. Â

For more on the Homer studio, see the Maine Sunday Telegram article from last Sunday and today’s piece here, the Associated Press story as published by the Washington Post, a travel story in The New York Times and additional articles listed here.

UPDATE: The Portland museum tells me that the previous top photo on this post, which I drew from the local paper, dated to 2006. They gave me a recent interior shot, which is now at top.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art (top), the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (middle), Alan Vlach via the Portland Museum of Art (bottom)