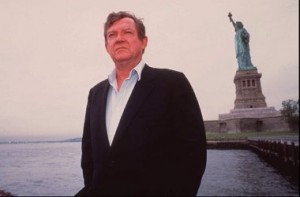

I met the critic Robert Hughes only once, and had no intention of writing about his death until I read a couple of his obituaries, which mostly ignored or belittled one of the things I admired about him. The New York Times didn’t mention it, neither did Time magazine‘s main piece (there’s apparently a separate story behind the paywall), and the Wall Street Journal, referring to a review of a book Hughes wrote, faulted him for it.

I met the critic Robert Hughes only once, and had no intention of writing about his death until I read a couple of his obituaries, which mostly ignored or belittled one of the things I admired about him. The New York Times didn’t mention it, neither did Time magazine‘s main piece (there’s apparently a separate story behind the paywall), and the Wall Street Journal, referring to a review of a book Hughes wrote, faulted him for it.

It was not his writing — everyone recognized his high style — or his eye, which agree with or not, signaled a distinct and definite taste, backed by erudition. No, I liked Hughes — an Australian who came to the U.S. via Britain — because he believed that American Art was/is underrated and did something about that — making an eight-part public television series called “American Visions” in 1998. That’s when I interviewed him.

My piece, A Critic Distills American Art into Eight Hours, describes the grueling work that went into the series, which was produced with comparatively little money given its ambitions;Â the accompanying 648-page book; and a special issue of Time magazine, where he was then critic (here’s an index to his work there). (Can you imagine Time putting out a special issue on art today?) Here’s an excerpt from my article:

My piece, A Critic Distills American Art into Eight Hours, describes the grueling work that went into the series, which was produced with comparatively little money given its ambitions;Â the accompanying 648-page book; and a special issue of Time magazine, where he was then critic (here’s an index to his work there). (Can you imagine Time putting out a special issue on art today?) Here’s an excerpt from my article:

…they filmed at more than 100 locations from Maine to Malibu — without the Hollywood conveniences.

“Whenever I’d see movie crews in SoHo, with their mobile toilets and makeup vans, I’d get jealous,” Mr. Hughes recounted. “Our makeup van was carried by a production assistant in her handbag. And when I was dripping in sweat, someone would produce a ratty package of Kleenex.”

The sheer volume of work was a bigger strain, threatening Mr. Hughes’s marriage and sending him to a psychiatrist for the first time. “After finishing the series about a year ago, I had severe depression,” he said. He blamed overwork, a crisis of confidence and postpartum blues.

Yet with deadlines for the book and then the bonus magazine looming, plus the reviews he writes for Time, there was no time to wallow. Sticking to a schedule he used on the road while writing the scripts, Mr. Hughes got up daily at 4 or 5 A.M. to churn out as many as 3,000 words a day.

“I nearly went bats having to write the book at such speed,” he said, dressed in blue jeans and a button-down blue shirt in his loft, which is chockablock with books and papers but devoid of art….

I can attest — 3,000 words a day is a lot; 3,000 good words is really a lot. But Hughes craved the accolades and attention his writing provoked:

Mr. Hughes has been noted for his idiosyncratic, nothing-is-sacred willingness to take on both the academically and politically correct, as well as for his vivid, irreverent language: when he says something clever, he will often stop to savor it and to make sure it has been recognized.

Over the years, it has been. Many deem him the most successful art critic today. In profiles and reviews of his books, writers have called him — besides the apt “ever voluble” — “erudite,” “famously pugnacious,” “brilliantly destructive,” “consistently entertaining,” “sardonic,” “pontificating” and a string of other colorful adjectives.

He is certainly “Nothing if Not Critical,” the title of his last book about art, a collection of his essays. In them, for example, he disparages the importance of Andy Warhol (on whom he has since mellowed) and taken many contemporary artists down a peg, including David Salle, Eric Fischl and Louise Bourgeois.

Hughes told me then that he wanted to make what became  “American Visions” as soon as he finished his more renowned “The Shock of the New” television series — which was broadcast in 1981. It took him until 1992 to enlist a backer — the BBC, not PBS, which added to the BBC funding, did Time, later.

Hughes told me much more in the course of our interview, worth reading if you appreciate Hughes — which artists he regrets leaving out, how he filmed at Monticello, why producers changed locations between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m., why he tied his choices to the land, and so on.

It’s worth reading, actually, even if you don’t like Hughes, and many people don’t. Even his detractors, however, agree that he made people go look at art, which is a good thing.