Cheim and Reid, the Chelsea gallery that shows work by many women artists, is circulating a recent piece in The Economist headlined “The Price of Being Female.” It starts with a disheartening paragraph about the recent contemporary auctions, which reads in part:

Cheim and Reid, the Chelsea gallery that shows work by many women artists, is circulating a recent piece in The Economist headlined “The Price of Being Female.” It starts with a disheartening paragraph about the recent contemporary auctions, which reads in part:

…Christie’s post-war and contemporary evening sale in New York earlier this month…was unprecedented…it had ten lots by eight women artists, amounting to a male-to-female ratio of five-to-one. (Sotheby’s evening sale offered a more typical display of male-domination with an 11-to-one ratio.) Yet proceeds on all the works by women artists in the Christie’s sale tallied up to a mere $17m—less than 5% of the total and not even half the price achieved that night by a single picture of two naked women by Yves Klein. Indeed, depictions of women often command the highest prices, whereas works by them do not.

Then it switched gears:

An analysis of data provided by artnet, however, suggests that the prospects for women are slowly improving. Compare, for example, the top ten most expensive male and female artists. Admittedly $86.9m, the highest price for a work by a post-war male artist (set by “Orange, Red, Yellow” by Mark Rothko) dwarfs the highest price paid for a work made by a woman—$10.7m for Louise Bourgeois’s large-scale bronze “Spider”. However, of the top-ten men, only two are living, whereas among the top-ten women, five are still working….

The Economist published a chart illustrating that point, using data supplied by artnet — here’s a link to it: ArtistsPrices.

I find it hard to put much stock in that tally, but the article makes other points, which are worth noting. The woman whose work seems most in demand is Joan Mitchell, whom The Economist dubbed “the turnover queen.” Since the mid-1980s, the date artnet’s records begin, her work has brought $199 million, all told, at auction. “Mitchell’s stature in the market,” the article says, “results from an international collector base, which includes Russian, Korean, French and American buyers. Abstraction always aspired to being a universal language; perhaps the new global elite will make it so.”

I find it hard to put much stock in that tally, but the article makes other points, which are worth noting. The woman whose work seems most in demand is Joan Mitchell, whom The Economist dubbed “the turnover queen.” Since the mid-1980s, the date artnet’s records begin, her work has brought $199 million, all told, at auction. “Mitchell’s stature in the market,” the article says, “results from an international collector base, which includes Russian, Korean, French and American buyers. Abstraction always aspired to being a universal language; perhaps the new global elite will make it so.”

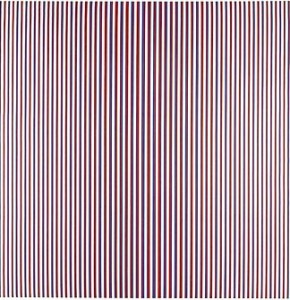

The living female artist record-holder is not, as I would have guessed, Marlene Dumas, but rather Cady Noland — “a reclusive figurative sculptor whose work explores the sordid underbelly of the American dream.” The top price for her is nearly $6.6 million, for Oozewald. Dumas comes next, at $6.33 million for The Visitor. Another surprise: Bridget Riley, whose Chant 2 (at right) fetched $5.1 million, ranks higher than Cindy Sherman, who comes in at No. 9 with a $3.9 million sale. The other living woman in the top ten is Yayoi Kusama, a Japanese artist whose work is less familiar (at least to me) even though the article says “Her work has the highest turnover of any living woman.” (No. 2 is above left.)

The Economist offers another positive note (for women artists) with this:

Intriguingly, the auction records for all three women—Mlles Noland, Kusama and Sherman—were the result of winning bids by Philippe Segalot, an art consultant who was then working for Sheikha Mayassa Al Thani, the Western-educated 29-year-old daughter of the emir of Qatar. It is probable that women feel a sense of affinity for art made by women. But perhaps more importantly, younger buyers and advisors find it weird to not include women’s perspectives in their collections. It appears the future will be more female. And as Iwan Wirth, a dealer with galleries in New York, London and Zurich, puts it, “Women artists are the bargains of our time.”

I realize that some readers don’t think that art should be scrutinized this way, as male versus female achievement. Maybe it shouldn’t. Sometimes analysis (including a few points in this) doesn’t (and can’t) go very far. But art is viewed through many prisms; this is just one. And there’s no harm in that.