Back to my lunch with Arnold Lehman, director of the Brooklyn Museum,* which ensued after I noted here that on a recent visit the special-exhibition galleries were full but the permanent collection galleries were empty.

This is a problem of museums’ own making. Over the years, they, aided by media coverage, have trained people to come for the special shows and nevermind the treasures they actually own. Now, with many museums cutting back on traveling shows because of

financial woes, the problem is growing.

financial woes, the problem is growing.

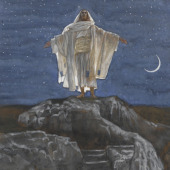

Brooklyn, it turns out, recently held a retreat on the subject. One obvious answer, hardly unique to Brooklyn, has curators devising “special” shows from their permanent collections — AKA “shopping in your closet.” In October, for example, Brooklyn will open James Tissot: “The Life of Christ” — an exhibition of 124 watercolors drawn from 350 that were acquired by the museum in 1900, at the urging of John Singer Sargent.

None of these watercolors (that is a detail from Jesus Goes Up Alone onto a Mountain to Pray, 1886−94, above) has been on view in at least 20 years; some haven’t been seen since the 1930s. They were first shown in Paris in 1894, and then went on the road to London, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and — Brooklyn. Lehman plans to peddle the show to four other museums, earning fees from them that will pay for conservation.

In a similar vein, To Live Forever: Egyptian Treasures from the Brooklyn Museum, which has been traveling for about a year and is going to about a dozen museums, will return to

Brooklyn in mid-stream (next Feb. 12 through May 2) for a visit. By then, the museum will have readied a special gallery for several mummies in its permanent collection (which has 11 humans and several animals, all told) that are not in the traveling show; it will focus on the after-life. That’s a mummy of Hor at left, entering the CT scanner at North Shore Hospital.

Brooklyn in mid-stream (next Feb. 12 through May 2) for a visit. By then, the museum will have readied a special gallery for several mummies in its permanent collection (which has 11 humans and several animals, all told) that are not in the traveling show; it will focus on the after-life. That’s a mummy of Hor at left, entering the CT scanner at North Shore Hospital.

All of this makes sense, and none is controversial. But it doesn’t address the problem squarely. There’s more.

Out of the retreat came the idea that curators will focus on “pods,” or thematic issues, to organize installations within the permanent galleries. Examples: religion, color, war & peace.

(The thought reminded me of a story I did for The New York Times in 2006, for which I asked novelists and writers what shows they would like to curate: the wonderful Francise Prose suggested an exhibit about black.)

Lehman calls this “an experiment to see how different elements throughout the collections can be used as one basis on which we hope to eventually reinstall all of the permanent collections.” That reinstallation, coming a couple of years from now, is likely to be more cross-cultural, more global in approach.

To illustrate and explain these “pods,” there’ll be gallery talks, tours and “many other programs.” Curators are already started on developing them.

Purists will undoubtedly dislike this approach. I think it’s worth a try. Execution will be everything — here’s hoping that these pods are based on sound scholarship, make interesting connections and are well-displayed. It’s a real challenge.

Interestingly, Lehman made the point that none of this was likely to be taking place had he not made his controversial curatorial reorganization in 2006. At the time, he did away with traditional departments, like Egyptian art and American art, and placed curators into two units, one for the permanent collections and one for special exhibitions. That was supposed to encourage new ideas and more teamwork. Curators screamed, and the museum was blasted in the press.

The jury is still out: I don’t always agree with the museum’s direction or its choices, but I do give Lehman credit for taking risks. Attendance has grown, and in other things, like technology, Brooklyn is a leader.

More about which another time.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Brooklyn Museum of Art

*Disclosure: I consult to a foundation that supports the Brooklyn Museum.