main: September 2010 Archives

I've always had a fascination with canons, even long before I

wrote a book about a composer (Nancarrow) whose major works were mostly canons.

In the late 1980s, when I was in the habit of lecturing on the history of Chicago's new-music scene at the School of the Art Institute and other places, I ran across,

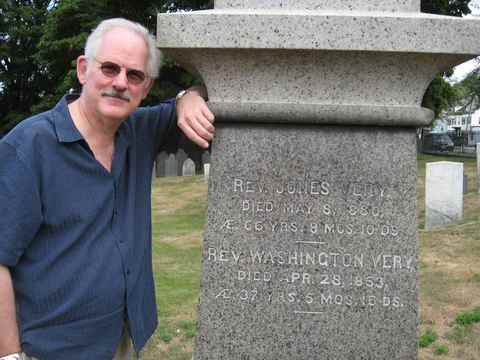

in a Chicago used bookstore, a little book called Canonical Studies, by Bernhard

Ziehn (1845-1912, pictured). I recognized the name. Ziehn was one of two German

composer-theorists who were living in Chicago when Ferruccio Busoni toured

through. Busoni was trying to solve the puzzle of how the four fugue subjects

fit together in the unfinished fugue from Bach's The Art of Fugue, and Ziehn

solved it for him, enabling Busoni to write his Fantasia Contrappuntistica,

which has long been one of my very favorite works in the world. His tour over,

Busoni wrote an article about Ziehn and his colleague Wilhelm Middelschulte,

titled "The Gothics of Chicago," by which term he meant that they were masters

and fanatics in the ancient art of counterpoint. Ziehn and Middelschulte taught

a lot of the early Chicago composers, including John J. Becker (one of the

"American Five"), whose widow I knew in Evanston. So I had multiple connections

to Ziehn, and snapped the book up at once.

All but forgotten today (there's a brief entry about him on

German Wikipedia, none in the English one, and the second reference that came up on Google was a page of my own), Ziehn was ahead of his time. Books

he published in the 1880s anticipated and classified chords (such as those

based on the whole-tone scale) that the impressionists and Schoenberg would use

considerably later. In the intro to Canonical Studies, Ziehn writes,

A canon is by definition strict. Our greatest authorities assert "strict" canons can be carried out in the Octave of Prime only. The examples given in this book demonstrate that real canons are possible in any interval...

And he gives examples of chord progressions that modulate to

every possible interval away from the tonic, showing how one can continue

repeating those progressions in ever-moving transposition to write canons not based on the

octave or unison.

I was intrigued, and in 1987 wrote what I call a "spiral

canon" as the third movement of my violin piece Cyclic Aphorisms, a canon at

the major second. Then, more ambitiously, in 1990 I wrote Chicago Spiral, a nine-part triple canon

also at the major 2nd, putting a postminimalist spin on Ziehn's idea. A canon

is easy to perceive as such at the unison, octave, or even fifth; it's more

challenging at a more distantly related interval. A canon is also easier to process aurally if the beat-interval of rhythmic imitation is something symmetrical like 4 or 8

beats, more difficult if it's 13 or 31. One thing I've realized is central to

my music is that I love to fuse the simple with the incommensurable, making the

listener think it ought to be easy to figure out what's going on, but keeping

it just out of reach. My Ziehn-inspired spiral canons ought to be simple to

figure out by ear - they're only canons, after all - but the complexity of the

imitation intervals, both rhythm and pitch, keep the ear, I think, from ever

quite settling into them. I also use the technique as kind of a postminimalist gradual-texture-metamorphosis generator, which is a little beyond what old Ziehn had in mind, I imagine. Paradoxically, the longer the rhythmic interval of imitation, the less gradual the changes can be made.

And now in recent months I've written two more such canons, Hudson Spiral and Concord

Spiral, both for string quartet. Along with the middle section of my orchestra

piece The Disappearance of All Holy Things from this Once So Promising World,

I've produced five spiral canons altogether, at the following rhythmic and pitch intervals:

Cyclic Aphorism 3: 5 beats, major 2nd ascending

Chicago Spiral: 7 beats, major 2nd descending

Disappearance: 17 beats, minor 3rd descending

Hudson Spiral: 83 beats, major 6th ascending

Concord Spiral: 19 beats, minor 7th descending

The major 6th and minor 7th are the optimal intervals for a string quartet canon; using a major 6th, the cello can play down to its low E-flat (echoed by the viola's low C string and second violin's low A), and the first violin can play down to the F# above middle C, whereas with the 7th the cello can descend to D and the first violin only to A-flat in the treble clef. Concord Spiral generated some nice passages of what sounds like tonal Webern:

The scores are on my web site if you're interested, and no performances are yet forthcoming. Spiral Canons and Snake Dances are the two personal genres I feel I've invented for myself, along with my more generic tuning studies and Disklavier studies. And I hope Ziehn would have been happy to know that, 98 years after his death, his idea is still out there making the rounds.

I've started to write you a few times or more, but didn't because I didn't know what to write or say or what to think or do - and I don't now - so I'll shut up! At least I can do all I can & I will to help New M[usic] Editions keep going as well as possible and as you would want...

I do hope you can keep well & that things will go well in the future.

The problem of whether you were gay or not didn't arise among the people that I was with. Ives was repressed but nonetheless he was a married man. [Yet] there was no problem. In fact that was the point I think that Ives made at the one luncheon I attended [with him]. Harmony was there and he, sitting off from the table, told me that when he was growing up, if you had anything to do with musicians it meant you were a sissy. Then he looked thoughtful and a little worried and said, "But all that seems to have changed now."

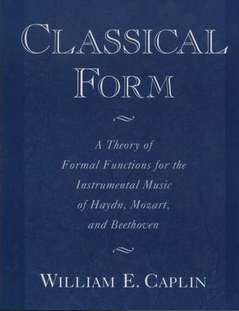

In my pedantically wonkish way, I'm excited to be teaching my sonata-form classes with William E. Caplin's book Classical Form (Oxford, 1998), as I have been for several years now. For those who don't know it, Caplin went through the complete sonata-form works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, and catalogued everything that happens in all of them - what theme the development starts with, what relative keys get referred to in the codas, and like that. I don't use the book as a textbook: even though Caplin's writing style is admirably clear, it's too dense and dependent on hundreds of examples, and to tell the truth, I've never yet gotten through the whole thing myself. Read four paragraphs and your eyes glaze over from the amount of detailed information you're trying to take in. (I once talked to someone at Oxford about how useful an undergrad-friendly version of the book would be, and she told me one was being contemplated.) But I've outlined chapters for my students as a kind of flowchart for what's possible in sonata form, and it's made it feasible to teach the subject honestly. I think when I was in school I was given some kind of "typical" sonata form chart (if indeed we ever paid any attention to any music before Webern, which I don't specifically recall doing), from which, of course, every sonata we ever looked at - deviated. But Caplin offers a descriptive plan rather than a prescriptive one. So yesterday in class we went through the outline, and then through movement 1 of Beethoven's Op. 2 No. 3 - and every move Beethoven made was one of the possibilities in the Caplin-based flow chart. One student, who had apparently gotten a whiff of the old prescriptive-style training, asked, "Can we look at a typical sonata first, one that follows all the rules?" And I said, "There's no such thing as a typical sonata. Might as well ask me to go out on the street and bring in a typical person." Instead of having to explain why every piece we listen to is an exception to most of the rules, I can teach the whole conception of sonata form as a range of possibilities and, better yet, meanings, some of which get chosen for identifiable logical or expressive reasons. It's nice to have one theoretical subject I can teach without making excuses for the lameness of the pedagogy. (Sometimes we look at Clementi, Dussek, and Hummel, too, and find some possibilities outside Caplin's range.)

In my pedantically wonkish way, I'm excited to be teaching my sonata-form classes with William E. Caplin's book Classical Form (Oxford, 1998), as I have been for several years now. For those who don't know it, Caplin went through the complete sonata-form works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, and catalogued everything that happens in all of them - what theme the development starts with, what relative keys get referred to in the codas, and like that. I don't use the book as a textbook: even though Caplin's writing style is admirably clear, it's too dense and dependent on hundreds of examples, and to tell the truth, I've never yet gotten through the whole thing myself. Read four paragraphs and your eyes glaze over from the amount of detailed information you're trying to take in. (I once talked to someone at Oxford about how useful an undergrad-friendly version of the book would be, and she told me one was being contemplated.) But I've outlined chapters for my students as a kind of flowchart for what's possible in sonata form, and it's made it feasible to teach the subject honestly. I think when I was in school I was given some kind of "typical" sonata form chart (if indeed we ever paid any attention to any music before Webern, which I don't specifically recall doing), from which, of course, every sonata we ever looked at - deviated. But Caplin offers a descriptive plan rather than a prescriptive one. So yesterday in class we went through the outline, and then through movement 1 of Beethoven's Op. 2 No. 3 - and every move Beethoven made was one of the possibilities in the Caplin-based flow chart. One student, who had apparently gotten a whiff of the old prescriptive-style training, asked, "Can we look at a typical sonata first, one that follows all the rules?" And I said, "There's no such thing as a typical sonata. Might as well ask me to go out on the street and bring in a typical person." Instead of having to explain why every piece we listen to is an exception to most of the rules, I can teach the whole conception of sonata form as a range of possibilities and, better yet, meanings, some of which get chosen for identifiable logical or expressive reasons. It's nice to have one theoretical subject I can teach without making excuses for the lameness of the pedagogy. (Sometimes we look at Clementi, Dussek, and Hummel, too, and find some possibilities outside Caplin's range.)Sites To See

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary