main: August 2010 Archives

The grim history of the twentieth century - something Brahms or Franck could never have foreseen, to say nothing of Matthew Arnold or Charles O'Connell - played its part as well both in discrediting the idea of redemptive culture and in undermining the authority of its adherents. The literary critic George Steiner, one such adherent, after a lifetime devoted (in his words) to "the worship - the word is hardly exaggerated - of the classic," and to the propagation of the faith, found himself baffled by the example of the culture-loving Germans of the mid-twentieth century, "who sang Schubert in the evening and tortured in the morning." "I'm going to the end of my life," he confessed unhappily, "haunted more and more by the question, 'Why did the humanities not humanize?' I don't have an answer." But that is because the question - being the product of Arnoldian art religion - turned out to be wrong. It is all too obvious by now that teaching people that their love of Schubert makes them better people teaches them little more than self-regard. There are better reasons to cherish art.

- Richard Taruskin, Music in the Nineteenth Century, p. 783

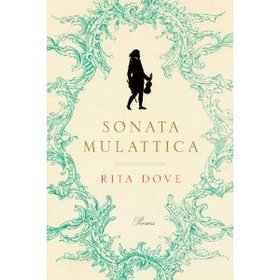

In The Barrow, I was going through poetry, and my eye ran across a title: Sonata Mulattica. I did a double take, chuckled in surprise. I tried to keep going. I looked at it again. I took it out, read a poem, put it back and moved on. But the book virtually leapt back into my hands. It's by Rita Dove, African-American poet who was poet laureate from 1993 to 1995. How can it be that the national poet laureate receives so little fanfare that I can fail to have heard of her 15 years later?

Anyway, Sonata Mulattica is an entire book of poems about a single subject: Beethoven's writing the Kreutzer Sonata for the "African prince" violinist George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower, falling out with him over a woman, and then dedicating the piece to Rodolphe Kreutzer instead. Dove uses lots of musical terminology, all correctly - in youth she played the cello, apparently - and her characterizations ring true and tired and humble, with none of the pompous mythologizing that attends portraits of great composers. Poem after poem after poem on this one moment in history, some from Bridgetower's perspective, some from Beethoven's, some from that of minor characters, and some of my favorites are about Haydn, who encouraged Bridgetower. This one is titled Haydn, Overheard (I'll refrain from entire poems for copyright reasons):

It is a sad thing always

to be a slave

but if slave I must, better

the oboe's clarion tyranny

than a man's cruel whims.

I stayed on at Esterhaza,

writing music for the world

between spats and budgets,

with no more leave

to step outside the gates

than a prize egg-laying hen.

Even after Miklós died

and his tone-deaf son

filled the courtyard

with military parades,

I hesitated: Call it

robbing Peter to pay Paul,

but I had been homeless once

and did not care for hunger....

But the finest gift I ever received

was the vision of Johann Peter Salomon

with his flamboyant nose and cape

swirling across my doorstep:

"I've come to fetch you," he said.

It was December. We set out

from Vienna on the fifteenth

for London, that great free city.

And here's Bridgetower, in a poem called Andante con Variazioni:

Thank you. It was a privilege. You are so kind.

It is all his doing; I am merely the instrument.

To have the honor of this premiere...

a beauty of a piece, indeed.

What an honor! Countess, I am enchanted.

I only wish I could better express my gratitude

in your lovely language: Vielen Dank.

It is all his - why, thank you, sir, I am speechless....

Herr van Beethoven is indeed a Master, and Wien

an empress of a city. My apologies -

I only meant that she is... magnificent.

(Ludwig, get me out of here!)

[UPDATE: In an attempt to better do the book justice, here's Beethoven:

Call me rough, ill-tempered, slovenly - I tell you,

every tenderness I have ever known

has been nothing

but thwarted violence, an ache

so permanent and deep, the lightest touch

awakens it... It is impossible

to care enough. I have returned

with a second Symphony

and 15 Piano Variations

which I've named Prometheus,

after the rogue Titan, the half-a-god

who knew the worst sin is to take

what cannot be given back.

I smile and bow, and the world is loud.

And though I dare not lean in to shout

Can't you see that I am deaf? -

I also cannot stop listening.]

It's a lovely book, a theme with variations indeed, and from every possible perspective. I could imagine reading about this episode and writing a poem, but an entire book of poems and so musically intelligent - it's quite astonishing. I considered ordering it as a textbook for my Beethoven course this fall, but I think I'll just put it on reserve, and make a much bigger deal than usual about the Kreutzer Sonata, which is one of my favorite middle Beethoven pieces anyway. Rita Dove: Sonata Mulattica (2009): highly recommended. And it's why internet shopping is not enough. I would never have run across this book on the internet, never known to Google "poems about Beethoven," never known who Dove was. Occasionally you have to walk into a really good, independent bookstore and finger every book on the shelves.

I also ran across The Thoreau You Don't Know (also 2009) by Robert Sullivan. It looks and sounds like a facile compendium of Thoreavian esoterica, but it's actually a brilliant revisionist biography, with the contradictory virtues of being breezily written yet withal extremely erudite. Its ostensive purpose is to rescue Thoreau's reputation from those who think he was an antisocial "Mr. Nature," by emphasizing the year he spent in New York City trying to get a start as a writer, the time he spent in court as expert witness for property disputes (being a surveyor), and his wise handling of the family pencil business. Having not had a superficial view of Thoreau myself (the book convinced me), I didn't need the revisionism, but I was impressed with how much mass culture Sullivan delved into in order to anchor Thoreau in his immediate society, researching 1840s sheet music and ladies' magazines, and the changes in agriculture brought about by the depression of 1837. The bibliography is kaleidoscopically diverse. Oxymoronically a thought-provoking page-turner, the book is a worthy opposite bookend to Robert D. Richardson's more introverted Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind.

For the purposes of this program:

• An Uptown Artist is an artist who lives and/or focuses their creative activities or aesthetic above 110th Street.

• A Downtown Artist is an artist who lives and/or focuses their creative activities or aesthetic south of 14th Street.

They noted that there were certain things which were impermanent and other things to which the word impermanence did not apply. - Perfect Lives

Sites To See

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary