main: March 2009 Archives

Now, just about every piece of music I'd ever consider teaching is stored on two external drives as mp3s, one drive at school and a duplicate at home. A lot of the music I teach is 18th- and 19th-century, and the bulk of that repertoire can be downloaded as scores on my desk computer from imslp.org. For 20th-century repertoire, I've scanned a lot of the music I teach regularly into PDFs, and I've traded PDF collections with faculty from other schools (I protect my sources), so I have hundreds of modern and postclassical scores on those hard drives as well. Now I carry no CDs or scores to school at all. It still feels strange to pick up my computer bag every morning with almost nothing but my laptop in it - like I'm going to work naked or something. With a touch more organization I could even leave that at home. If I start to play something and find it's not on my hard drive (as happened recently when I tried to make an unanticipated foray into Giya Kancheli symphonies), I write myself a note and rip the CD to my computer when I get home. I can always make a class out of the 16,000 mp3s I've got with me (it's a larger collection than Bard's CD library). If I don't own a piece I need, I can plug into the internet at school and play it from the Naxos music library service we subscribe to.

I save a lot of paper by projecting PDF scores from my computer onto a screen, rather than making individual copies for all the students. When I do need to copy something, I print a PDF and run it through the machine, rather than stand there laboriously turning the bound score over page after page. If I need to research something for class, say, find some repertoire for an assignment so obscure that students can't look up the composer, I do it all on the internet rather than in the library, and spend many more hours at home than I used to. (Of course, students can take advantage, too. I am told of a grad student who was given a take-home test of anonymous pages from orchestral scores to identify as closely as possible by style. Seeing the publisher's score number at the bottom of each page, he simply Googled each number and correctly identified every piece.)

My extensive PDF collection of 20th-century scores will make it sound like I'm one of the scofflaws responsible for the gradual death of music publishing, but not so. I used to go to Patelson's in New York and buy whatever attractive modern scores they had, which were never many. Occasionally I would order something, but it almost never came. Now, I scour the internet for scores, and find obscure things Patelson's would never carry. I've been buying more printed, commercial scores than ever, because the internet allows me to find what I need. (And believe me, I've done about as much to keep poor Patelson's afloat as any mere academic could be expected to do.) Many of the PDFs I use for teaching are made from scores I paid for, and if I break copyright laws, it's usually to get access to music that the music publishing companies somehow can't manage to keep in circulation - often music that they'll rent for performance, but won't sell. Of course, almost all the postclassical scores I have were home-produced by the composer and never entered the commercial marketplace at any level. I get the music legally if possible, but I get it.

And though I seem a little ahead of the curve by musical standards, I'm a Luddite compared to some of my colleagues in other fields. They use something called Moodle that lets them store all their teaching materials on the internet, including letting students upload their papers, which the professor corrects on the browser and reposts. We've got professors who walk into class empty-handed, having everything on the computer, and never touch a piece of paper. Of course, for that, you need a "smart classroom" with a computer terminal, which we can't seem to get in the music building (though I'm first in line every time they're offered), and for wireless we musicians walk around the halls like we're dowsing for water, trying to tap into the film department's wireless next door. Also, our current Moodle system can't quite accommodate the space-intensive audio files I need. (The year the library offered to put reserve recordings on the internet, my first and legitimate request was Der Ring des Nibelüngen. They balked.)

(Also, imslp, though I'm its biggest fan, is a work in progress. Aside from highly variable scanning quality, I recently downloaded Schumann's Davidsbündlertanze only to find that imslp's copy is labeled Davidsblündertanze - David's Blunder Dances? - right on the music. I tried to leave a complaint, but couldn't access any page at imslp to do so.)

But I'm astonished at how much less paper there is in my life, how much more time I spend at home, how much less time I waste searching for objects, how much less it matters where I am, and how many more materials I have access to anywhere I go. Not once this school year have I driven back home because I had forgotten something. Also, I used to, like many composers, show up at any performance with an extra copy of all the parts, just in case. Now all my parts are posted on my web site at non-public URLs. You want to perform a piece of mine, I'll e-mail you the URL. When I fly around the world to lecture I upload my lecture and examples to the internet, and print them out when I get there, if not simply project them on a screen. I carry almost nothing.

Preben Antonsen (b. 1991): Dar al-Harb: House of War

Kyle Gann (fl. 1440s): War Is Just a Racket

Frederic Rzewski: Peace Dances

Jerome Kitzke: There is a Field

Phil Kline: The Long Winter

The Residents: drum no fife: Why We Need War

Terry Riley: Be Kind to One Another (Rag)

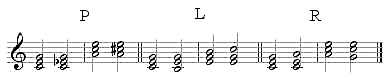

The L function lowers the root of a major triad a half-step, or raises the fifth of a minor triad a half-step, creating a new triad of the opposite modality in either case. The R function raises the fifth of a major triad a whole-step to produce the triad of the relative minor, or lowers the root of a minor triad a whole-step. And there are some other derived functions, such as D, which does from a triad to its dominant, or vice versa. And functions can be combined, so you get PL, RP, LPL, and so on. If I'm oversimplifying or getting it wrong, some kind reader will correct me.

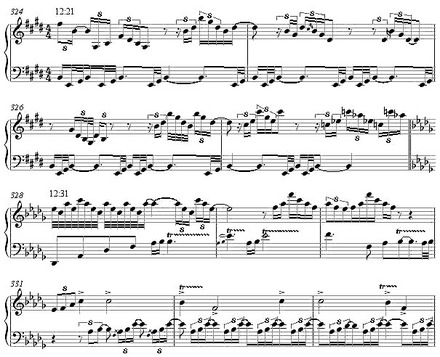

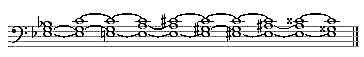

The occasion of my bringing this up was my biennial analysis of a gorgeous passage from Liszt's Années de Pelerinage, the beginning of "Sposalizio," which is hardly complicated, but notoriously recalcitrant to Roman numeral analysis:

Now instead of calling that i-VI in E minor and wondering where in hell the B-flat major came from, I could label the sequence L, RLRL (or DD, since C to B-flat is two dominant jumps), PR, D, PR. It doesn't really explain the music - though the PR does make clear the equivalent jumps from B-flat to D-flat and A-flat to B, which the enharmonic pitch notation hides - it just gives me a way to label Liszt's key jumps, more radical in their unconcern for tonality than Chopin's or Schumann's. And I think the students enjoyed learning a theoretical technique that wasn't from the musty, immemorial past, but evolved during their lifetimes.

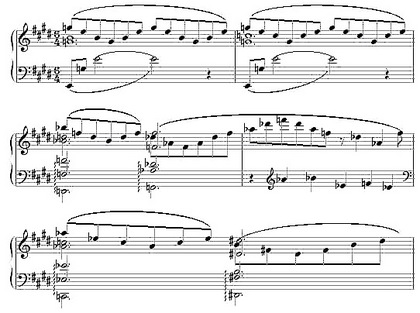

The even greater interest for me is the potential application to my own music. In 1983, I switched over, with some trepidation, to writing in a triadic style, though not at all functionally tonal. I had been studying Bruckner and taking tips from passages like this wonderful one from his Eighth Symphony:

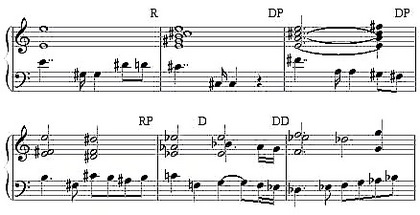

(Interestingly, in the immediate repeat of this passage Bruckner replaces the RP with a PR, and ends up in D major instead of A-flat.) I soon found myself rather obsessed with what I now learn are called LPL and RPR transformations (the latter yielding a tritone transposition). Here's Baptism, from 1983:

The chord changes, if I have parsed them correctly with my amateur notions of Neo-Riemannian terminology, are PLP, RPR, LPL, RPR, LPL, LPL, RPRP, LPL. Note that no chord change requires fewer than three transformations - that was my conscious discipline for the piece, but of course I wasn't thinking of it in Neo-Riemannian terms, which hadn't been invented yet. This was pretty much my default harmonic language from Baptism of 1983 to my "Last Chance" Sonata of 1999. In 2000 I studied jazz harmony with John Esposito, and switched over to bebop chords. My microtonal music uses a process of micro-interval voice-leading that Harry Partch called "Tonality Flux," related to Neo-Riemannian transformations, but of course not reducible to them. However, the large-scale tonal structure of my 2002 microtonal chamber opera Cinderella's Bad Magic consists of a chain of simple Riemannian pitch shifts, all tuned to pure triads and evolving from E-flat major to C double-sharp minor, through single note-shifts R P R P L P R P L:

These Neo-Riemannian labels neither explain nor justify my music, but they do give me simple ways to refer to my voice-leading methods as classes of harmonic transforms. And, as papers at the last minimalism conference proved, Gavin Bryars and John Adams were using a similar kind of non-functional harmonic consistency from the early 1980s on as well. This terminology can make it easier to point out how the harmonic practices of Liszt, Bruckner, and Reger returned, following the period of widespread atonality, to form a new common practice in minimalist and especially postminimalist music - starting, I think we'd have to say, with Einstein on the Beach, whose "Spaceship" scene may succumb to only this kind of analysis. Neo-Riemannian theory may fill in some cracks in our analysis of Romantic music, when dealing with composers who couldn't abide within the Germanic idea of a centralized tonality. For postminimalism, it may prove to be the analytical technique that fits the music like a glove.