main: July 2008 Archives

Let's take that mythical animal, "the audience." "You can't talk about the audience, there is no such thing as the audience." Well, these days I live like a hermit, but keep in mind that for many years I attended five concerts a week, often two or three in an evening, at ten or 15 usual spaces all over New York. I became very aware, among other things, of how a performance that drew cheers from one audience might get blank stares from another, and it was to some extent predictable. I saw the audiences more regularly than I did the individual performers, and got to know them better. I ranged the city from Avery Fisher Hall to King Tut's Wa-wa Hut; if you only get your new-music fixes at, say, Miller Theater and Carnegie Hall, you may never have learned enough about audiences to realize how much, and how predictably, they can vary.

I knew the BAM audience (best, most nuanced audience in America), the NY Philharmonic audience (worst and rudest), the Kitchen audience (hip but not very spontaneous), the Experimental Intermedia audience (all friends, and undemonstrative), the Chicago jazz audience (very savvy and good-humored, intense listeners). I sat in the Chicago Symphony audience among people who'd made up their minds before they came in, half believing that Georg Solti was a god who could do no wrong and the other half convinced the orchestra would never again be what it used to be under Reiner. I sat at Roulette in the middle of an early '90s John Zorn audience indistinguishable from a Barack Obama rally today - you betrayed divergence from the prevalent riotous approval at your peril. I sat, or stood, in the Knitting Factory and CBGBs (on new music nights) among audiences whose members, aside from myself, ranged in age from 21 to 23. These toddlers made no distinction between one act and another, one piece and another - they weren't appraising the music, they were learning the scene, mindful to show a hip level of enthusiasm, but afraid to look uncool. I would observe the audience's reactions as a counterpoint to my own, and these post-pubescent audiences were worthless for that - it was like I was the only subjective consciousness in the room.

I've seen audiences lie, in both directions. I've seen audiences spend the duration of a performance bored and restless, flipping through their programs, and then burst into a standing ovation when it was over, because the music was something they were "supposed" to approve; and I've seen audiences get caught up curiously and very attentive, and then applaud tepidly and speak slightingly of the music during intermission, because the composer's reputation was still in doubt. On the other hand, I've seen a sophisticated audience all start backward at once at a daring turn in the middle of a fantastic ROVA sax quartet improv, and another all suddenly burst into a guffaw when Rzewski slyly quoted Beethoven. We all like to believe in free will and have faith in the integrity of our individual judgments, but you put 300 people in a room together, point them at a stage, and give them a stimulus, and certain kinds of groupthink take over, except perhaps for an intransigent, peer-pressure-hating curmudgeon like myself. Add to that that audiences tend to be fairly self-selecting, based on venue. If the audience generates a groundswell of enthusiasm, nothing can afterward shake the faith that that reaction was directly attributable to the music itself. That's often how reputations get made, and then you move the same music to a larger, more formal venue where it falls flat, and everyone gets confused. But if the audience is a well-tuned, sensitive instrument, its behavior can draw a revealing map of how the music works.

The late, great Jim Tenney was someone who'd always tell me, "You can't generalize about the audience, everyone listens differently." Well, Jim probably rarely went to the local symphony or the Knitting Factory, but to small new-music concerts where he was surrounded by like-minded individuals who were unusually focussed on their own individual judgment, and, expecting to compare notes with their peers afterward, pretty free from collective bleed-through. Within his usual haunts, he was probably right - you couldn't generalize about his audience. But Virgil Thomson says somewhere, and I don't want to go look it up so I'll paraphrase it and ruin it, that what being a critic teaches a composer is a realism about what can get across to an audience and what can't, and the sad truth that an effect cannot be communicated simply by wishful thinking. When I talk about "the audience" I may have BAM in mind if I'm thinking of a perfect world, or the NY Phil in mind if I'm thinking of them as a bunch of shits who don't deserve anything better than Kenny G, but I am thinking of an entity that possesses, for me, a palpable presence. Maybe it's you who can't generalize about the audience.

Likewise, I'm hyper-sensitive, perhaps, to the kinds of groupthink that run through the composing world, for which we composers bear, in my view, a collective responsibility. For instance, it's kind of standard to say today, on one side of the line, that in the 1970s composition teachers pushed their students to write 12-tone music or some suitably complex-sounding equivalent. But I don't think that's quite what happened. It seems to me that the real pressure came not from faculty, but from peers and the general environment, and that a kind of macho competitiveness based on compositional systems became an inescapable undercurrent. Probably the professors, who in their own minds were trying to be fair and impartial, took a little more encouraging interest in the students whose music reflected their own interests, and that subtle preferential treatment spread throughout the student body as an emotional charge connected to compositional systems, to which some students gravitated and against which others rebelled, but no one was allowed to remain neutral. That would explain both why so many students remember a perception of having been pushed toward systematic thinking, while so many professors feel injured by any such suggestion. And I was at Oberlin; we'd have Midwest Composer Symposia, and I'd learn that the dynamics were a little different at U. of Michigan, and different again at U. of Iowa.

On composition panels, I'm always the one who notices that, out of 73 orchestral scores by young composers, 19 of them start out with a dramatic single tone crescendoing into a burst of percussion, and of course I immediately disqualify those 19 as composers who've succumbed to the clichés of their time. (One of Feldman's talents was for identifying clichés no one else would recognize as such - like the facts that, in the '70s, the standard orchestra piece had become 20 minutes, and the default tempo quarter-note equals 72.) Contrarily, I notice a 7-against-6 pattern running through a piece by Ben Neill, and then an 8-against-9 in Evan Ziporyn, and a 6-against-7-against-8 in Glenn Branca, and it occurs to me that there's a movement going on, and I coin an -ism, and man, does that piss everyone off. I am not supposed to call attention to the things I notice - if they conflict with the article of faith that each one of us is absolutely unique like a snowflake, and impervious to outside suggestion or unconscious imitation, or even picking up ideas that are "in the air." (Hey, have you noticed that all snowflakes have six sides?)

Among all good liberals, generalizations took on a bad odor in the '70s, as though they were all of the same form as, "all Blacks are great dancers," or, "Jewish people are good with money." My mother had a great put-down line for people who drew conclusions from too little evidence; she'd respond, "All Indians walk single file. I saw one once, and he did." More recently, though, the idea of groupthink has entered our political discourse as an attempt to describe what goes wrong within professional circles. We composers have groupthink too - and how are we supposed to identify groupthink if we are forbidden to generalize, or notice recurring patterns? The prohibition against generalizing can be a political tool for preventing the recognition and exposure of groupthink. No wonder certain people are so violently opposed to it.

Well, forgive me for being me. I just paint what I see as clearly as you'd paint a tree in your front yard, but being a Scorpio, I perceive the substrata more clearly than the surface. I see patterns, I draw connections, and since no one else sees them, or they're all focused on other things instead, I must be up to something sinister, or perhaps just crazy. If my descriptions find no resonance they will fade away quickly enough, but I can only employ the talents I have.

So it will gratify some of you to know that I am now listening to Grisey's Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil for the second time this evening - if only to nettle the less mature Kyle Gann of two days ago. I was dogmatic in my youth, but at some point many years ago I started a campaign to cultivate flexibility, and I still surprise myself.

OK - there's no such thing as "The Nazis," either. Some Nazis shot Jews in the head with apparent unconcern, others felt quite anxious and guilty doing it, and still others managed to get themselves confined to clerical work. You can't generalize about the Nazis, because each one was an individual who acted and felt differently. And if we composers can prevent people from generalizing about new music, then complaints will be limited to individual cases like, "On Sept. 22, 1982, Andrew Imbrie's Cello Sonata made Walter P. Syasset of Fort Lee, New Jersey, wish that he had never let his wife talk him into coming to this boring concert." That will free the composing community from any collective responsibility for their actions, and there will never have to be any self-questioning within the profession as to whether there's perhaps something wrong with our pedagogical trends, or too much cronyism in the selection of award and commission committees. Anything amiss will be deemed at the most an infraction by a single composer, and since each listener's response is entirely subjective, we'll all be off the hook forever.

Only one problem: what if there are people who refuse to limit themselves to the modes of discourse that we've declared permissible?

("You don't mean like, Kyle Gann?")

If we can agree on two propositions, I have some faith that all the rest will fall into place. Let's posit a musical idiom that I think most of you have heard or can imagine: thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand. Proposition 1: not every thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand piece that's been written is a masterpiece, worth listening to over and over again. Some pieces in that late-20th-century idiom are merely tedious and unclear, confusing rather than profound. I hope everyone concerned (except for Frank Oteri, who prides himself on a Zenlike appreciation for every piece that's ever come into existence, simply for existing) can agree on this much.

The second proposition may be a little more difficult to get universal agreement on among non-musicians. Proposition 2: at least some thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand pieces are beautiful and profound, and those listeners who come to know them well derive immense pleasure from them. In short, within the wide world of thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand music, we're going to draw a theoretical line. On the profound side of this line, for instance, I would place Bruno Maderna's Grande Aulodia, which is like ear-candy for me, and also Luigi Nono's late string quartet Fragmente: Stille, an Diotima. On the confused and unrewarding side of that line I might place as example Charles Wuorinen's Concerto for Cello and Ten Instruments, which I excitedly bought a score of as a teenager, and which ever since has served me as an emblem of pretentious musical gobbledygook. But it doesn't matter which pieces, or even which percentage of pieces, you put on which side of that line - as long as you'll simply agree with me that there's a line, we can continue.

All I'm asking you to do is dissociate the qualities complexity and quality. Complexity does not guarantee that a piece of music is great, nor does it guarantee that a piece of music is bad. Put that way, I don't think even our friend Frank can disagree.

(Already now, though, two people have written to express suspicion that if I think some complex music is no good, then I must secretly think that all simple music, or all tonal music is good. Aside from such assertions being patently ridiculous, there would be no logic whatever in such a leap of thought. Like, "You don't like some kinds of chocolate? Then you must love everything that's vanilla!" But in general musicians are not very good at logic, and this is the kind of fallacy that these arguments of musical style get caught up in.) [UPDATE: Darcy James Argue, in commenting on the above, makes a welcome clarifying point: "In practice, in certain circles... it is effectively impossible for anyone to make an argument that flows from Proposition 1 (especially: "this piece of thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand music is in fact a piece of shit") without people assuming that you are in fact launching a full-bore assault on Proposition 2 ("so you're saying that all my favorite thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand music is worthless???")"]

As is pretty clear, the Nonken argument does its level best to ignore Proposition 1 ("Vote NO on Proposition 1!"), and the Byrne argument ignores, or even disputes or refuses to acknowledge, Proposition 2. Yet to ignore either of them negates the deeply-felt experiences of large swaths of people. Of course there are thousands of musicians who have been deeply and positively affected by some thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand music that would have seemed opaque and unpleasant to my grandmother. Byrne's view (as he expressed it, and perhaps he doesn't believe it as simplistically as he said it, but he gave voice to a common formulation) is a cliché, the cliché of Evil Modern Music, but it is not a cliché that was made up out of whole cloth. Clearly a lot of people think music went off some kind of deep end in the 20th-century, and became (temporarily) self-delusional. As a critic, as a composer, as a person, I have an obligation to acknowledge both sets of opinions; I can't tell either my composing colleagues nor the musical audience I used to write for that their perceptions are totally neurotic - at least without losing credibility with one set or the other. Much of my life has been spent on this dividing line.

Let's take that opinion that classical music went off some kind of deep end in the 20th-century, and became self-delusional. There is absolutely no way to assess the sanity of this assertion without dividing the music alluded to into several repertoires with different reception histories:

Pre-WWII Modernism (early Stravinsky, Varèse, Schoenberg, Webern, Bartok, Ives, Messiaen, etc): This music certainly disturbed older members of the audiences who first heard it, and it became the first repertoire of music shunned by orchestras. It definitely represents a split, apparently irrecovable, in the classical repertoire. That music exploded into a lot of musical areas that had been previously off-limits, using dissonance, complex rhythms, and atonality to express violence, anxiety, machinism, and anger. Of course, as is widely documented, today when orchestras play that music, the older crowd who loves their Brahms and Dvorak get irritated or stay away, but thousands of new, younger listeners pour in. The movies have done a lot to inure the modern ear to dissonance and arrhythmia, and also to associate it with analogous emotional states. For my students in general, the traditional relationship is now reversed: 19th-century symphonies seem tedious and unthinkingly conventional, while early modernism is entertaining and energizing, like the audio analogue of a video game. Reception history suggests to me that the jury is in on early modernism: arguing that it was a wrong turn seems as pointless an argument as any Luddite could make. Let us say no more about it in this context.

European avant-garde of the 1950s and '60s: This, as the rainbow of reactions to Zimmermann's Die Soldaten shows, is more problematic territory. That music hit the recording world when I was in high school, primed and ready for it, and I glommed it up with hungry ears, reading everything about it I could get my hands on - and even to me, some of it doesn't make sense. That music, too, used dissonance, atonality, and arrhythmia - but not always to express violence or anguish, often just to play with sound forms. My students get a perennial kick from Stockhausen's Gruppen, but whether its fragmented textures could ever cease to suggest anxiety to the untrained ear is something I would not want to speculate about. A lot of that music's drive was theoretical, and it trailed off into a thousand dead ends, a thousand pieces more remarkable for the pompous psychology of their program notes than for their sonic aura. Nevertheless, a core repertoire of tremendously beautiful and original works emerged from all that experimentation: Boulez's Pli selon pli and Rituel, Zimmermann's Photoptosis and Monologe, Berio's Sinfonia and Corale, and, you can make up your own list. If I were called upon to justify Darmstadt serialism to a general audience, I'd say, "Wait a minute - which pieces am I justifying here? Because I'm sure as hell not going to go out on a limb for all of them." I insist that there are pieces on both sides of the line in that repertoire, some gorgeous and some merely confused, but they are so unified by idiom that a general audience has to be forgiven for finding it difficult to make distinctions.

Comparing the reception history of this music with that of the next category is complicated by the fact that Europe and the U.S. have such different musical cultures. In Europe an immense festival culture grew up around serialism, which gave a convincing appearance that there was more public support for the music over there. Some Americans, like Rzewski, came to write more opaque music after expatriating to Europe, as though that had more success there, and it probably did. Nevertheless, I always think of the parents I once met of an exchange student at my son's elementary school. They were from Graz, Austria, and I mentioned that I was aware of a prestigious contemporary music festival there. They said, "Oh, the music they play there is terrible, all this horrible modern stuff. We go every year."

Academic 12-tone music of the 1970s and '80s: You may deny, if you wish, that in the period in question, thousands of student composers were encouraged by their professors, or perhaps pressured simply by their peers or the environment, to write abstract music of exploded textures in a 12-tone idiom, or something resembling it. Go ahead and deny it: an army of survivors will rise up to contradict you. Dissonance, arrhythmia, complexity, had, if you wanted, become completely dissociated from any specific emotional expression; it was often all just about pitch sets and sound structures. There is no need to demonize this period, which simply resulted from the collision of European serialism with an explosive expansion (in both size and influence) of academia in the directions of composition and analysis. But neither let us whitewash the fact that the "contemporary music concert" nurtured by academic culture became, for awhile, something of a chore. Even my fellow students and I, thoroughly indoctrinated into this culture, couldn't believe how bad most of the music was, semester after semester. Something was clearly wrong, and later that something got fixed to a certain extent. Just to take one example, student composer concerts I've heard in the last ten years are so infinitely better than student composer concerts of the '70s that someone should write a book about that phenomenon alone.

Whether you agree with my characterizations here is really not important. What's important is that contemporary classical music got a terrible public reputation in the mid-20th century, and while composers at first defended the music, at some point, even many of us began to concede that something had gone wrong. Where one draws the line that got crossed over (1945, 1970, serialized rhythm, pitch-set analysis) is immaterial. Certainly recent reception history suggests that some of that bad rep was unfair - and some, Frank, will argue that all of it is unfair, but many composers of my generation, myself included, cannot not go that far. Camus wisely said, "You are what other people think you are," and Morton Feldman's grandmother used to tell him, "When three people tell you you're drunk, lie down." There is a factual basis to the Byrne argument that it simply does not do us any good to ignore. At the same time, we need the Nonken argument so that we don't throw the baby out with the bathwater. In fact, those two arguments complete each other. We can't accurately describe the 20th century without both of them.

One of the arguments that composers bring up over and over again to buttress the Nonken argument is that all composers write the way they do from deep inner compulsion, and so there's nothing they (or you) can do about it. I simply don't buy this. It does not accord with my experience. It's true of some composers, and maybe they're the ones saying it, or perhaps it is a romanticization of the creative artist by their enablers. I've seen too much evidence to the contrary. I had a brilliant, ambitious student once who studied scores by composers who won prizes - thinking that if he could write the way they did, maybe he could win prizes too. I've known composition teachers who told their students, "Here's how you write a piece of music," and the student followed instructions and got in the habit of composing that way - often being well rewarded for doing so because the teacher, pleased with their obedience, afterward helped them get awards and commissions. Even I myself have been known to depart from my usual stylistic inclinations in order to accommodate the sensibilities of the people who gave the commission, who might want something more "classical-sounding" and emotive (or possibly just easier to perform) than my usual fare.

Much music, much good music, is written the way it is because the composer has gotten so excited about hitherto underused ramifications of the musical structures she's found in other people's music that she sees a wonderful creative opportunity to take music in a new direction based on those ramifications. That's probably the core paradigm (or at least, it's the more professionally realistic version of the composer "having something deep within her soul to express"). But a composer's idiom is influenced by a hundred forces, some unconscious, some carefully calculated, some financial, some vain, some noble, some inspired, some in habitual response to academic training. And the superficial impulses are no more guaranteed to produce bad music than the noble ones are to produce good music. The audience's reflexive skepticism toward new music is, in itself, no more unjust than the skepticism with which you are approaching this article right now - waiting for me to show my hand, waiting to catch me in some fallacy.

It seems to me that I haven't said a controversial or non-commonsensical thing here yet, though I will. To create a healthy musical culture, we need a shared reality. The Nonkens need to admit to the Byrnes that upon occasion a composer has wasted the audience's time with a pompous, confused piece written in ambitious but misguided imitation of earlier works; the Byrnes need to admit to the Nonkens that music may be capable of wonderful large-scale effects that one needs experience and a well-conditioned ear to hear. Where audiences and where composers will tend to draw the line will always differ, and that's good: it gives us a big gray area to argue about, and art is always furthered by being argued about. But nothing is to be gained by claiming that the composers have never, ever been at fault, nor by denying that audience members could gain something from extending their listening capacities.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

So far so good, I hope.

I read the first three chapters of Finnegans Wake once. I laughed, I cried, it was marvelous. For years I thought at some point I'd go back and finish the book, but with each passing year it looks a little more doubtful. It's an incredible, heady pleasure, like nothing else in the world, but fully absorbing that pleasure takes considerable time and energy. Maybe when I'm retired.

What if there were dozens of books like Finnegans Wake? I hear that there are. I haven't read any William Gaddis, I never finished a Thomas Pynchon novel, and I bought Hermann Broch's The Death of Virgil because of its connection with the composer Jean Barraqué, but didn't get very far into it. And I'm a voracious reader, always have a couple of books going at least. I'm sure all those books are very good. If I were a literature professor or reviewer of books, I would have dutifully taken the time to get through all that stuff. But I'm just a pleasure reader, except for when I'm reading things for my own scholarship.

As a music aficionado and writer, I did do all that for many behemoths of 20th-century music. I combed Sinfonia for quotations, analyzed the entire tempo structure of Gruppen, listened repeatedly to Barraqué's Sonata and looked at the score, went through Carter's Double Concerto countless times, devoured Boulez's On Music Today and painstakingly compared its prescriptions to Le Marteau, read Babbitt's articles and book, and did my homework. I sometimes notice, though, that the big, complex pieces that I've really gotten to know well were ones I studied back between 1973 and 1986, when I was in school and just afterward, before I started at the Village Voice, before my son was born, when I had plenty of time on my hands. The crazes for Helmut Lachenmann and Gerard Grisey came along later in my career. I've listened to their CDs at times and thought, "Well, if I had time to listen to this over and over, maybe I'd start to get more out of it." And, a couple years later, I've listened again - and put the CDs back with exactly the same thought. That today's grad students find Lachenmann and Grisey as exciting as I once found Wolpe and Maderna, and consider me something of an old fogey for not hopping on the bandwagon, makes perfect sense. They've got the time, and the available memory. New experiences make a deeper and quicker impression on them, as they once did on me.

The qualities of complexity and opacity do not guarantee that a piece is good, as we've established above, nor do they guarantee that a piece is bad, as we've also established. It takes time, working one's way slowly into each piece, work by work, to judge how good something is. The question is, of course: how much complex, opaque music can the world afford? How many more complex, opaque pieces can I be expected to internalize in my life than the couple hundred or so I've already absorbed? New CDs arrive in the mail every week. According to the paradigm by which musicians usually talk about music, when a CD contains simple music, I probably listen to it once, say "That's nice," and then put it on the shelf; and when the CD is of complex music, I listen to it over and over, getting more from each new exposure. But what actually happens is closer to the opposite: when the music is relatively simple, it has a visceral impact on me, and soon I want to hear it again, and it starts becoming part of my mental audio furniture, and I start writing about it and recommending it to people. And when the music is complex, I'm more likely to say, "Well, if I had time to listen to this over and over, maybe I'd start to get more out of it." Some of those CDs never get listened to again. For others, the second and third listenings are much like the first.

The defenders of musical complexity already have their angry fingers on the "comments" button, but wait - musical complexity needs no defense from me. I love Pli selon pli, remember? I bet I know more of Maderna's music than you do. That, at this point in my life, composers who can get their main musical ideas across in a listening or two get more of my attention than those who demand 12 or more listenings plus some reading and analysis is not a sign that I am superficial of soul. It is a sign that I am no longer a grad student, and that I am swamped with responsibilities. (I remember, when I studied with him in 1975, Morton Feldman being particularly caustic on this point. He'd criticize a student's piece as unclear, and the student would protest, "But you have to listen to the piece more than once," and Feldman would sneer, "Kid's 21, and he thinks I'm going to listen to his fuckin' piece twice.") (Maybe he didn't say fuckin', but it was clearly implied.) You can say, because it is one's duty to say so, that the pleasures that come from complex music run much deeper than those that come from simple music, and that the time spent getting familiar with a difficult masterpiece will pay off much more than the ten easier pieces I might have studied in the same span. But this hasn't uniformly been my experience. In my imagination, I think of Nono's Stille, an Diotima and Bill Duckworth's relatively simple Time Curve Preludes as being about equally great pieces; but the truth is, I haven't listened to the Nono in ten years, and I feel a need for the Preludes at least a couple of times a year.

Another popular escape hatch: "You don't need to understand complex music to enjoy it, just sit back and experience it." Yet something tells me that if I simply listened to Ferneyhough's [Ha! I mentioned him] Transcendental Etudes as passively as I do to Cage's Winter Music, I would miss many of the crucial things Ferneyhough put into it. (I actually heard Ferneyhough lecture about that piece at the U. of Chicago, so I know something of how it works. I like it OK. Don't listen to it often.) I think, too, that had I taken that Cagean approach years ago to Boulez and Stockhausen (or hell, Cage, for that matter), I wouldn't today enjoy their music on as many levels as I do. I'm not opposed to the idea that a repertoire might necessitate score analysis and book reading to fully appreciate it. I just don't know how many more composers I'm going to have time to do that with in my life, nor how many the avid lay music lover ought to be expected to study similarly. Nor do I, as a result, find composers I've done that with - like Boulez and Stockhausen - deeper or more appealing than composers like Virgil Thomson or William Schuman who never necessitated any such study.

Allow me a brief detour. There is an ancient tradition in aesthetics, and a wise one, I think, that simplicity in art is a virtue. I insist that one of the things we proved in the 20th century is that it is not a necessary virtue, that it may not be the best virtue - but it remains a virtue. Some will recognize the following quotations from my writing:

True genius is of necessity simple, or it is not genius.... The most intricate problems must be solved by genius with simplicity, without pretension, with ease; the egg of Christopher Columbus is the emblem of all the discoveries of genius. It only justifies its character as genius by triumphing through simplicity over all the complications of art.... Genius expresses its most sublime and its deepest thoughts with this simple grace; they are the divine oracles that issue from the lips of a child; while the scholastic spirit, always anxious to avoid error, tortures all its words, all its ideas, and makes them pass through the crucible of grammar and logic, hard and rigid.... - Friedrich von Schiller, "On Naive and Sentimental Poetry")

Simplicity is the most difficult thing to achieve in this world: it is the last limit of experience and the last effort of genius. - George Sand

In products of the human mind, simplicity marks the end of a process of refining, while complexity marks a primitive stage. Michelangelo's definition of art as the purgation of superfluities suggests that the creative effort consists largely in the elimination of that which complicates and confuses a pattern. - Eric Hoffer

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication. - Leonardo Da Vinci

And allow me to add one more quote which will haunt you forever, my fellow Americans, a quotation that has appeared in countless books, and that will live as long as American music itself lives:

I began to feel an increasing dissatisfaction with the relations of the music-loving public and the living composer.... It seemed to me that composers were in danger of working in a vacuum... I felt it was worth the effort to see if I couldn't say what I had to say in the simplest possible terms.

Aaron Copland, of course, about the time he wrote El Salon Mexico. "I felt it was worth the effort," he says. Modernists draw a narrative around Copland that his thorny Variations for piano was a great, forward-looking work, while Billy the Kid was a terrible backsliding into mindless populism. But as Copland expert Larry Starr has aptly and truly written, "not only is this ballet score as sterling an illustration of Copland's basic methods as either the Piano Variations or Music for the Theatre; it also reveals these methods at a stage of greater maturity and refinement." Starr's right: study the scores, and you'll see that Billy the Kid is a more sophisticated score, gunfight and all, than the Variations. Copland did not weaken his music in simplifying it - he sharpened it.

Here's that escape hatch: Anyone who's an obsessed fan of a particular complex, opaque piece can always claim that what that piece expresses couldn't possibly be expressed any more simply, and it's a claim pretty much impervious to opposing rhetoric. Thank god for the ambiguity and subjectivity of art, and there will be no Q.E.D. at the end of this article. What he cannot claim, though, I think, is that music generally improves with complexity and opacity, nor that simplifying can't sometimes sharpen a composer's art. At the very least, complexity and opacity tend to withdraw a piece of music from the public sphere, while simplifying increases its public availablility. Ives's most public image, after all, is one of his simplest and (yet) most powerful pieces, The Unanswered Question.

Simplicity, Copland reminds us, requires effort. It is, for me, a sign of courtesy in a composer, of his urgency in wanting to reach me, that he is willing to work to sharpen his musical argument by simplifying it as far as he can without falsifying it. And before someone assumes that I am carrying arround some boneheaded, dumbass notion of simplicity, I do not mean reduction to quarter-notes and eighth-notes, but rather the streamlining and agreement of all elements of a piece to create a unified, singular impression. I hear now and then that some stranger thinks my Private Dances is my best piece; it is certainly my simplest piece, though there are some pretty hairy rhythms in it (including a dance in 29/4 meter). Like Copland, I sometimes take great pains to simplify what I try to say in my music for maximum public effect, and those pieces seem to get across well; other times, I want to do something that just won't reduce to simpler terms, and only my fellow composers realize what I've done. I've always thought Beethoven got the proportions right: he wrote an Eroica Symphony and a Ninth Symphony that showed the masses exactly what he was about, then a Grosse Fuge and an Op. 111 Sonata that made most of his contemporaries think he was mad. Had all of Beethoven's music been as dense and counterintuitive as his last sonatas and string quartets, we would still consider him a genius today, but he would have come down to us as a much smaller, more eccentric figure.

What does this portend for the would-be composer of complex, opaque music? Of course he is free to write what he wants, keeping aware that as the amount of complex, opaque music in the world grows, the time available for the dramatic needs of his own contribution shrink in proportion. He is content, of course - naturally! - to settle for a very small, very serious audience. Perhaps he is ambitious enough to think he can knock Gruppen off its pedestal, so that next year he'll be in the curriculum instead of Stockhausen. If such a composer wants his music to reach an avid but beleaguered music lover in middle age such as myself, the want of the virtue of simplicity will need to be made up for by some pretty dazzling compensatory virtues. Failing that, he will always have for his audience the grad students - who have time and incentive to decipher his intricacies, and who may well continue to love his music into their dotage for the intellectual challenges it provided them in youth.

There are lots of books exploring what the fuck happened with 20th century classical music, when many composers willfully sought to alienate the general public and create purposefully difficult, inaccessible music. Why would they do anything that perverse? Why would they not only make music that was hard to listen to, but also demand, as in the case of Zimmerman, that the piece be performed on twelve separate stages simultaneously, with the addition of giant projection screens and other multimedia aspects? Were these composers competing to see whose works could be heard and performed the least? Why would anyone do that?

Having closely observed the behavior of New York's downtown, avant-garde music scene for a few decades, I can say that this impulse is not limited to academic classical composers. There are many musicians and composers of experimental works who seemingly compete for the title of most obscure and most difficult for the listener, and even record collectors like to play along. In this world, any trace of popularity, however slight, is distasteful and to be avoided at all costs. Should a work become unexpectedly accessible, the artist must then follow the piece with something completely perverse and disgusting, encouraging members of the new, undesired audience to walk away shaking their heads, leaving behind the core of pure and hardy aficionados. This is elitism of a different sort. If one can't be fêted by the handful of patrons at the Met, then one can be just as elite by cultivating an audience equally rarified in the completely opposite direction. Extreme ugliness and unpleasantness becomes the mirror image of extreme luxury and beauty.

This passage suggests that Byrne has not closely observed the behavior of the Downtown scene for a few decades, for had he closely observed it, he would have noticed that a broad swath of Downtown music - not all of it, admittedly - has been devoted to music of great beauty, clarity, and accessibility. (Not that those are the only musical virtues: some of the music included in the above critique I'm probably a fan of.) From a certain angle, clearly the only angle from which Mr. Byrne sees it, that multifaceted creature Downtown music has been encapsulated as the world of John Zorn, Elliott Sharp, and their cohorts, who during the 1980s unfortunately succeeded in obscuring the fact that Downtown was first the world of Steve Reich, Charlemagne Palestine, Pauline Oliveros, Laurie Anderson, Elodie Lauten, William Duckworth, and a few hundred others. Byrne's eloquent attack is pitch-perfect as far as its appropriate target goes, and still relevant; still, he's about 25 years late in failing to recognize that hundreds, perhaps thousands of composers had already agreed with him by 1980, and set about doing something about it. Quite a bit about it, actually.

This month's Musicworks magazine contains an interview with me, written by editors Gayle Young and David McCallum, and titled "Pitch and Rhythm Guy," which is something I called myself during the course of the interview. The accompanying disc contains two pieces of mine, the final scene of Custer and Sitting Bull in its sparkling new rendition with the sounds redone by M.C. Maguire, and a keyboard piece called Triskaidekaphonia, which I've written about here before. Gayle and David generously let me ramble on about my music, including my relationship to jazz harmony, astrology, microtonality, American Indian music, and so on. I feel I internalized pretty early in life that the next thing to do in music was to find new subtlety and new kinds of organization in music's two highest-profile parameters, pitch and rhythm - just as most of the music world was giving up on those directions as having been perhaps exhausted, though there were a number of composers of my generation who made a fetish (in the best sense) of performable rhythmic complexity.

This month's Musicworks magazine contains an interview with me, written by editors Gayle Young and David McCallum, and titled "Pitch and Rhythm Guy," which is something I called myself during the course of the interview. The accompanying disc contains two pieces of mine, the final scene of Custer and Sitting Bull in its sparkling new rendition with the sounds redone by M.C. Maguire, and a keyboard piece called Triskaidekaphonia, which I've written about here before. Gayle and David generously let me ramble on about my music, including my relationship to jazz harmony, astrology, microtonality, American Indian music, and so on. I feel I internalized pretty early in life that the next thing to do in music was to find new subtlety and new kinds of organization in music's two highest-profile parameters, pitch and rhythm - just as most of the music world was giving up on those directions as having been perhaps exhausted, though there were a number of composers of my generation who made a fetish (in the best sense) of performable rhythmic complexity. The use of gamuts is among the most practically useful aspects of our inheritance from Cage.

When we freeze the tonal space, we shift the focus of our music away from the manipulation of notes to listening to the sounds. It doesn't matter whether the elements of a particular gamut are obviously related at the outset. When we hear the music, we hear the continuity, the continuum of the sounds. The use of interval controls (a la Harrison) does something similar. In fact, I often use interval controls to create my gamuts. So Lou's observation to Daniel Wolf [see comments] makes good sense to me.

[UPDATED] In February of 1948, John Cage gave a lecture at Vassar, heralding his intention to write a silent piece:

I have, for instance, several new desires (two may seem absurd, but I am serious about them): first to compose a piece of uninterrupted silence and sell it to the Muzak Co. It will be [3 or] 4 1/2 minutes long - these being the standard lengths of "canned" music, and its title will be "Silent Prayer."

Probably this is too simple, and admittedly I don't know about the exact technology used by Muzak, but I don't think it's quite coincidental that 3 and 4 1/2 minutes are about the limitations of the 10-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm records of the day.

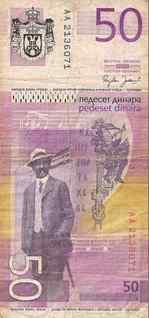

For instance, did you know that a Serbian composer, Vladan Radovanovic, claims to be the first minimalist composer, having started in 1957? (I'm really sorry that I can't provide Serbian diacritical markings, but my word-processing software isn't up-to-date enough to handle them, nor am I confident that Arts Journal could represent them.) Dragana runs into him occasionally, and he's miffed that she hasn't credited him yet. And here's national composer Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac, pictured on the country's 50-dinar note (about a dollar):

(The 100-dinar note boasts national hero Nicola Tesla, who figured out a lot about electricity before Edison did.)

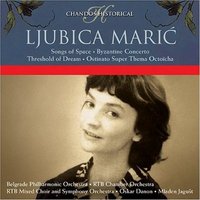

But easily the most fascinating story in Serbian music history is that of Ljubica Maric (1909-2003, pronounced Lyubitsa Marich, with a "ch" like church and accents on both first syllables). She was Serbia's most important and innovative modernist composer before World War II. Now, how many other countries can claim that their pioneering modernist composer was a woman? Like, zero? Gotta hand it to Serbia. And, to be a chauvinist pig about it for a moment, early photos like the CD cover here show that Maric was just about the most beautiful composer in the history of music, strikingly modern-looking in the 1930s. She lived to be 94, and Dragana used to see her at concerts, but was too shy to speak to her.

But easily the most fascinating story in Serbian music history is that of Ljubica Maric (1909-2003, pronounced Lyubitsa Marich, with a "ch" like church and accents on both first syllables). She was Serbia's most important and innovative modernist composer before World War II. Now, how many other countries can claim that their pioneering modernist composer was a woman? Like, zero? Gotta hand it to Serbia. And, to be a chauvinist pig about it for a moment, early photos like the CD cover here show that Maric was just about the most beautiful composer in the history of music, strikingly modern-looking in the 1930s. She lived to be 94, and Dragana used to see her at concerts, but was too shy to speak to her.

Maric studied with Josip Slavenski (1896-1955), who had absorbed Bartok's ideas about incorporating folk music into symphonic music, and there is a strong Bartokian streak to Maric's music, though the folk music influence is rarely obvious. She later studied in Prague with Alois Haba of quarter-tone fame, and wrote some quarter-tone music which is unfortunately lost. She got rave reviews for a wind quintet played in Amsterdam in 1933, and spent some time conducting the Prague Radio Symphony. But World War II interrupted her career, and afterward she was inhibited by Yugoslavian communism's antipathy toward modernism, so that her total output is rather small. She revved up her muse again in the late 1950s, however, and the only works I've heard of hers, on the pictured Chandos disc, are from the period 1956-63. The most immediately engaging of them is her Ostinato Super Thema Octoicha (1963), which is based on a repertoire of Byzantine medieval religious songs called the Octoechos; I've uploaded an mp3 of it for you here. The Byzantine Piano Concerto and Sounds of Space contain remarkably beautiful and original passages as well; she very much had her own voice.

Teaching at the Stankovic School of Music and then at Belgrade Conservatory, Maric was into Zen and Taoism, and lived a reclusive life despite interest shown in her music by Shostakovich, among others. From 1964 to '83 her pen fell silent, then she started composing again. She made some tape music performing on not only violin but cutlery, jewelry, and dentist's equipment, but refrained from ever releasing it. She was a fascinating figure, Serbia's Ives, Crawford, Bartok, and Cage all rolled into one. There's a scholarly essay by musicologist Melita Milin about her career in the 1930s here. It all makes me think that the Balkan countries need to be more regularly incorporated into the historical narrative of 20th-century music.

Experiences No. 1

Experiences No. 2

I've been looking for newer recordings, on CD. But every other recording I find is too fast, too textural, too "expressive," too classical - too Uptown. They're ultrasimple pieces, all white keys, nothing but pentatonic scale in No. 2. As with much of my own music, I sense that classical musicians find the bare notes too uninteresting, and think they have to "interpret" them to breathe life into them. There seems to be no sense anymore that a pure, stately, slow melody (such as one finds in Renaissance polyphony or Japanese Gagaku) can be beautiful. Post-Ligeti, post-Carter, post-Debussy, everything has to be turned into texture, into an illusionistic surface that transcends the notes. No! No!, a thousand times no! Sometimes the notes, played slowly and with dignity and clarity, are all one needs, as in Socrate, as in Musica Callada, as in In a Landscape, as in Snowdrop, as in Symphony on a Hymn Tune, as in The Art of Fugue.

It strikes me, though this would be difficult to document, that the '70s were a high point for performers understanding that principle, and we're now in a deep trough, because lately I've had a difficult time getting performers to play my simple music slowly enough; they encounter so little technical challenge that they start to rush, trying to buoy what they fear is dull music through some hint of the virtuosity they're so proud of. But such music turns trivial when played as quickly as it's easy to play it, as does much of Cage's music of the 1940s. Bernas and Wyatt and Eno, coming from the pop world, exhibit far and away a more instinctive understanding of the Zen simplicity Cage was aiming at than any of the more recent renditions. I fear I'll never find another really beautiful recording of Experiences 1 & 2 again.

An odd thing about Experiences No. 2 is that Cage omitted the final two lines of Cummings's Sonnet, which I think are the best lines:

turning from the tremendous lie of sleep

i watch the roses of the day grow deep.

But it's still a gorgeous song, and most gorgeous of all when sung the clean, blank way Wyatt sings it.

My mother used to teach piano, and got her Master's Degree in music ed. One summer when I came home from Oberlin, I brought her a cassette tape of the music I had had performed during the year. She played it, and didn't say much right away. Later that day, she suddenly sighed with relief and said, "I'm so glad you're not writing 12-tone music."

Now, imagine me reading that slowly, with pauses between the phrases, and with David Tudor making electronic noises in the background. Doesn't that sound like it could fit in the recording Indeterminacy? Or try this one:

Ben Johnston's priest advised him to try out Zen meditation, but the closest Zen temple was in Chicago. Ben began driving to Chicago every week, and so I would meet him at the temple for my composition lesson after the Zen services, rather than drive down to Urbana. During lessons, Ben's colleague Heidi von Gunden would serve us tea in traditional Japanese manner. Finally I began showing up two hours early, to go through the Zen services with Ben. After each session of zazen, my compositional inspiration would suddenly open up, and my head would be flooded with musical ideas.

Later, when I moved to New York, I attempted to keep up my Zen practice. The monks at the New York temple, however, quite opposite to the ones in Chicago, looked down their nose at meditators who needed pillows to sit on, or who couldn't make it through a 45-minute session without being struck on the shoulders. Put off by their snobbishness, I never went back.

I've never thought of my life as being the kind susceptible to story-telling, but plunging back into the stories that Cage sprinkled liberally throughout his early books has made me rethink. All you have to do is isolate some comment you remember, or event or change of mind, state it flatly with no affect in as few words as possible (or with an optional colorful phrase or two), and - most important of all - without context. By doing so, Cage spread such a Zen flavor around these stories, like they were koans, making his life seem like a series of nonsequiturs in which all the people around him were slightly crazy. Memorized by musicians of my generation and repeated by every biographical commentator for lack of better documented information, these stories stand almost as a smoke-screen against those trying to get insight into Cage's life. So many of them end in absolutely opaque punchlines that cry out for explication:

"We don't know anything about her coat. We didn't take it."

"You know, I love this washing machine much more than I do your Uncle Walter."

"You're too good for us. We're saving you for Robinson Crusoe."

Recognize them all, don't you? And though he didn't start publishing them until the age of 49, all those enigmatic little stories seemed so perfectly hip for the upcoming '60s decade whose humor would be defined by nonsense and nonsequiturs like the ones spearheaded by the TV show Laugh-In. It was an amazing anticipation of the ethos of a new era, and reminds you that in his brief career at Pomona College, Cage was known, not as a musician, but as a short-story writer. It strikes me that the stories in Silence had every bit as much to do with Cage's exploding popularity as the actual lectures and essays did. His sense of style was elegant and irresistible, but, as it turns out, entirely imitable. I'll try one more:

In college I had a tremendous crush on a student actress I'll call Leona. To say the crush was unrequited would be an understatement. One day in the library I ran across her kissing another woman, and decided that was the reason. Almost twenty years later, however, I was talking to my college friend Bill Hogeland, and Leona came up. Bill admitted that he had had an affair with Leona after graduation, but added that she made him uncomfortable because she worked in a strip club.

UPDATE: All right, maybe that last one is a Morton Feldman story. I'll try another, though one you've heard here before:

It was the dress rehearsal for the opening night of New Music America. At Orchestra Hall, Dennis Russell Davies was rehearsing members of the Chicago Symphony, who were having a difficult time negotiating the constant meter changes of Steve Reich's Tehillim. The rehearsal was to end at 5, and as the hour approached, Reich stood up and announced that the piece wasn't ready, that another hour's rehearsal would be required. Maestro Davies looked out into the hall for a representative of the festival, and found only myself, administrative assistant, aged 26. He asked for permission to keep the orchestra onstage another hour. I ran out into the lobby and tried, without success, to locate the festival directors by phone. Not knowing what else to do, I walked back in and, as though someone with authority had told me to do so, shouted, "Go right ahead!" The performance went fine, and no one ever mentioned, on that day or any other, the extra $15,000 that my "go-ahead" cost the festival.

We're inviting all scholars working in the area of minimalist music to submit proposals of papers for presentations of 20 minutes each. Possible subjects include, but are not limited to, the following:

- both American and European (and other) minimalist music;

- early minimalism of the 1950s and '60s;

- outgrowths of minimalism into postminimalism, totalism, and oher movements;

- minimalist music's relation to pop music or visual art;

- performance problems in minimalist music;

- analyses or investigation of music by La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich,

Philip Glass, Arvo Pärt, Louis Andriessen, Gavin Bryars;

- especially encouraged are papers on crucial but less public figures such as

Tony Conrad, Phill Niblock, Jon Gibson, Eliane Radigue, Rhys Chatham, Barbara Benary, Julius Eastman, and so on.

Deadline for proposals, from 300 to 500 words, is October 31, which should be e-mailed to

kgann@earthlink.net (Kyle Gann)

and

compositeurkc@sbcglobal.net (David McIntire)

The committee to select papers will consist (as of now) of myself, Keith Potter, Pwyll ap Sion (codirector of the first conference, and author of a new book on Michael Nyman), and Andrew Granade.

The first such conference was a tremendous success. We all enjoyed being able to talk freely to academic colleagues about repertoire not always granted much respect in academia. This time we've got some dynamite performances lined up, including some seminal minimalist works that haven't been heard publicly in decades. We'll be sending this invitation out via various mailing lists shortly, but this is the first public announcement. Please spread the word to anyone you think would be interested. Mikel Rouse has promised to treat us to the world's best barbecue, which apparently can be found in Kansas City! We've gone about as fer as we can go.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog