main: March 2008 Archives

To call post-war atonality "the Dark Ages" is so entirely retarded, I'm beside myself. If anything, post-war serialism... exposed more light on what music was, is and can be, and was nothing short of a cultural revelation. Post-war atonality made today's taste for oblique tonality possible. It's like women today who disparage the hard-core feminists of the 60s and 70s, even though today's women are reaping the benefits that those unsightly, nail-spitting bull-dykes risked social derision to gain.

The literature of expostulation, of Catastrophe, is taken to be very serious. But among people carried along in a canoe toward a waterfall, the one who stands up and screams is not the one with the keenest sense of the situation. We are in a place so difficult that perhaps alarm is an indulgence, and a harder thing - composure - is required of us.

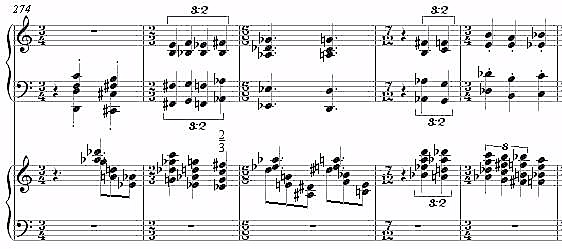

How's it look? This is how far I've succeeded in notating meters like 2/3, 7/12, and 5/6 in Sibelius. I have to put in a false meter, input the notes, delete the meter, insert the real meter via "Text > Special Text > Time Signatures," and then add the brackets manually. I can't decide whether it's clearer to put a "3" over two or four quarter-note triplets or "3:2." And I wish I could put a space in that bracket for the number. Suggestions welcome.

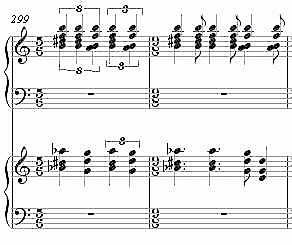

Those examples are from my I'itoi Variations of 1985. I admit that since I started using notation software in the mid-90s I shy away from meters like that - though Sibelius has opened up a myriad other possibilities in multitempo music for Disklavier, so it's a trade-off. I notice that Michael Gordon, the other composer I know of to use unconventional tuplet groupings the way I do, always seems to expend considerable ingenuity in aligning his tuplets so that they'll fit within a conventional meter - at least in pieces I have scores of, like Yo Shakespeare:

and Trance:

If I'm going to use this idea at all, I find this solution too limiting. I want 7/5 meter, and 25/13, and the whole megillah.

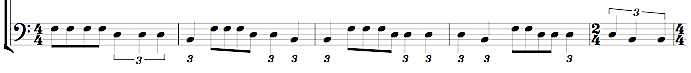

[UPDATE:] Not only is it too limiting, ultimately I think it's too difficult to perform. Michael writes these kind of rhythms for new-music groups, and they negotiate them well as a chamber-music kind of thing, but I've never seen him try it with orchestra. For conducting purposes, I think it would be easier to notate the passages of his above as alternations of 2/4 and 2/3 meter, which would also allow the music to expand outside the 4/4 framework. For instance, I can't imagine maintaining a 4/4 beat through the Trance example above, but I think my examples could be conducted.

I think that humans are capable of learning to switch to a tempo 2/3, or 4/3, or 3/4 as fast as a preceding tempo - and that, in fact, the composers of my son's generation are pushing us toward that capacity.

I haven't blogged about Alex Ross's The Rest Is Noise simply because I hate being one of a crowd, and if someone else is saying the things I would say, I have little incentive to say them myself. But I find myself rather delighted by the mini-controversy of Alex getting carped at by a couple of European critics on British radio, as detailed at Sequenza 21 (you can get a link there if you want to hear the original radio program, I found it difficult to operate). That the European critics' arguments are so pathetically, blusteringly weak is the surest sign yet of the strength of Alex's book.

One of them finds it unfathomable that Copland gets more pages of the book than Debussy and Ravel put together. Hmmm... well, let's see, Debussy lived from 1862 to 1918, Ravel from 1875 to 1937, and Copland from 1900 to 1990, and if your project is to chart the rising and falling course of modernism after Strauss's Salomé (1905) up to the end of the century, it looks reasonable to me that Copland put a lot more of his productive years into that era than... well, than Debussy and Ravel put together. (For that matter, the kneejerk assumption that either Debussy or Ravel had more impact on the direction of music than Copland strikes me as old-fashioned and in need of its own defense at this point.) Another complains because Ralph Vaughan Williams is not presented as a major figure. To each his own. Another considers that Alex's bleak assessment of post-Stockhausen German music is flatly contradicted by the liveliness of the current scene in Berlin.

Well, I do hear a lot of good things about Berlin over the past several years, partly because a thousand American musicians seem to be over there. But the context of Alex's discussion was German music of the 1980s and '90s, of which he has this to say (redundant, because I know you've already read it):

...the emergence of the new Germany as the dominant player in the European Union failed to distract the country's composers from their wary brooding over the past; indeed, Germans and Austrians seemed more conscious than ever before of the "danger of resembling tonality," as Schoenberg once put it. Sixty year after the Wagner-loving Hitler killed himself in Berlin, pundits could still be heard declaring that clear-cut repetition of material or a nonironic use of triads betrayed a fascist mentality.... [T]he mantle of greatness fell on Helmut Lachenmann, who has said, "My music has been concerned... with the exclusion of what appears to me as listening expectations performed by society." One analyst approvingly notes that Lachenmann's work is "uncontaminated" by the world around it....

...[M]uch contemporary music in Austria and Germany seems constricted in emotional range... The great German tradition, with all its grandeurs and sorrows, is cordoned off, like a crime scene under investigation.

Upon first reading the book, I had written to Alex and singled out this passage for praise. Not only does the description perfecly capture my impression of German composing culture in the period 1980-2000 - more significantly, it jives exactly with what I've been told about that scene by young German and Dutch composers who have left or avoided the scene to escape it. If you hold up a mirror to a people and they say, "Don't make me look like that," the only response possible is, "Then don't look like that." I do get a sense that things have been changing rapidly in Germany and Austria in the last several years, but the 21st Century is not the subject of Ross's book. As commonly noted, it says "Twentieth Century" right on the cover, and its European critics have had to attack by charging him with having unfairly omitted the 19th and 21st.

One point brought up in the blogosphere in Ross's defense is that The Rest Is Noise is a narrative, not a music history text. As someone who has argued for the primacy of subjective narrative in musicology, I see this as something more than a defense. Were I to teach a general 20th-century course, I could easily imagine using The Rest Is Noise as my textbook. It would give me a second subjectivity to use as a foil to my own, like having another professor in the classroom to argue points with, rather than duplicate my own idiosyncratic views. Plus, and not unrelatedly, it's so readable that the students would actually read it and remember things. For similar reasons I would have loved to use Carl Dahlhaus's wonderful 19th-Century Music in classes as an intelligently revisionist history, but Dahlhaus is over my students' heads; he assumes the reader already knows the history he is about to refurbish. The Rest Is Noise does not have that pedagogical liability. It would be a mistake for musicologists to dismiss The Rest Is Noise on account of its frank subjectivity of viewpoint, and I don't get the impression that American musicologists are flirting with that mistake.

It would likewise be silly, I think, or at least premature, to take this handful of logic-challenged critics as representative of European reaction in general. The show's host, after all, praises the book highly after the others have vented their spleen. But it's curious to see European musicians now in the position that Americans have occupied for a century, as the ones who feel marginalized and left out in the classical music dialogue. Their horror that a mere American has wrested the steering wheel of classical-music history out of their hands is palpable. It makes me want to go back and review several generations' worth of European music books that condescended to American composers, including the recent British compendium I once wrote here about that included the blithe statement,

"It is difficult not to come to the conclusion that in terms of musical impact, and in the reflection of the wider human condition and the narrower expression of the ethos and ideas of the day, none of the American composers has yet matched their European counterparts."

Poor Brits and Germans - they're beginning to see what it feels like.

This YouTube video of a young John Cale playing Satie's Vexations on the TV show I've Got a Secret is indicative of a time when our civilization was very, very different than it is now. I don't remember this episode, but I well remember watching I've Got a Secret when I was a kid, and I remember Garry Moore. (Thanks to Alex Martell for the tip.)

Having some free time this week (translation: none of the people I owe work to were hounding me), I started revamping my web site once again. The aim is to both streamline and expand it, in imitation of composer web sites I envy like Erling Wold's, Alex Shapiro's, and Eve Beglarian's. I'm obviously not much concerned with graphic sophistication. The Hudson Valley doesn't provide me with kelp to drape over myself, like Alex has out there on the Pacific Coast (though if I took a walk through the Hudson I'd probably emerge with some pretty picturesque, if carcinogenic, muck). But it bothered me that my mp3s were on one page, PDF scores on another, program notes accessible somewhere else, and I'm remodeling it on Erling's everything-in-one-table format. My brother Darryl set up my web site in 1996, and for 12 years I've been getting by on what HTML tricks were available in the primitive 1990s. I know now I could probably do something cool like make the eyes in my photo blink, but I'm putting utility above aesthetics.

As for the expansion, I took off most of the recordings that you now have to go buy my new CD Private Dances to hear, but I've added lots of obscure recordings that no human has heard in years. Like my Homage to Cowell (1994), the piece that got cut for space from my Custer's Ghost CD, and which uses a single looping, carefully-tuned drum sample to imitate Cowell's Rhythmicon; Imaginary Isle (2003), the little piece I wrote for Trimpin's installation of nine MIDI-operated toy pianos; and Snake Dance No. 1 (1991), which I had quit listening to because I like No. 2 better, but No. 1 has some advantages I'd forgotten about. Plus I've put up everything from the out-of-print Custer's Ghost until I can bring it back out in some new format. Clicking on the pieces that are commercially recorded will take you straight to Amazon.com, so have your credit card ready.

I reiterate that I do all this not because I perceive a hue and cry begging for my minor works, but because I'm so physically disorganized that it's reassuring for me to have everything on my web site, where I'll know where to look for it and how to find it. I've even started keeping documents there to which there is no public access, because I'm weary of losing things in the Bermuda Triangle I call my office.

While I'm at it, anent our discussion of online PDF scores, I had forgotten that Eve Beglarian offers her scores online. And I've been meaning to note that Art Jarvinen's Leisure Planet site has a very interesting collection of scores for modest prices. Music-score culture's transition to the internet continues slowly but surely.

This may be a subject that has been widely discussed since I was in grad school, I dunno, I don't ride the theory circuits much. But does anyone know why Bartok so meticulously put timings on each section of his scores, showing exactly how long they were supposed to last? Joseph Szigeti asked Bartok about it, and he evidently replied, "It isn't as if I said: 'This must take six minutes, 22 seconds...' but I simply go on record that when I play it the duration is six minutes, 22 seconds." I can buy that with Bartok's piano pieces, and there have been studies comparing the timing of his recordings with that given in the scores. But with ensemble works like the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, or even an orchestra piece like Music for SP&C, how did he know? I've read that he timed his performances, divided by the number of beats, and used the timings to set the metronome markings. What, did he look at his watch while conducting? Anyone know more than I do? It seems totally crazy to me, and students will ask again this year, as they do.

Wow. WOW.

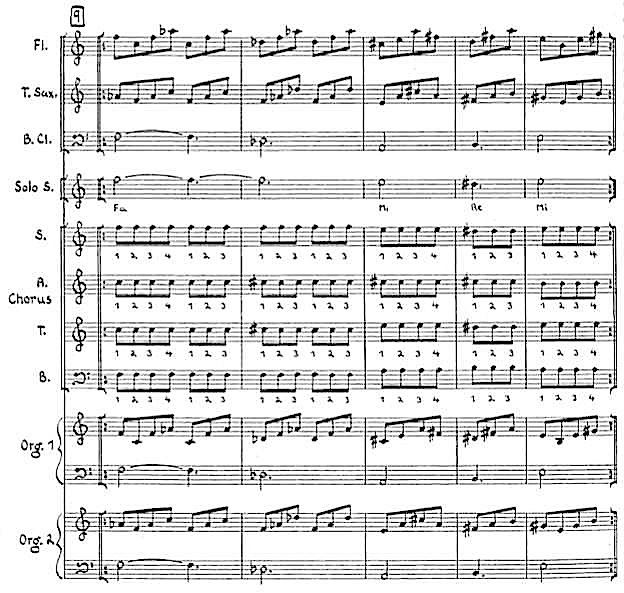

As you can infer, I am holding in my hands a copy of the score to Einstein on the Beach. I can hardly put it down. I ordered it from Chester Music, and it just came in the mail. I had come to think I would never own such a thing, because for so long Philip Glass had refused to release the music written for his ensemble, since performing it was how he made his money. But it's finally available, and next semester I'm teaching an analysis class based on minimalism and its offshoots. So before I committed to the course, I searched around to see what minimalist scores I could get, and I found more by Glass and Terry Riley than I had thought would be available.

It's not that I consider Einstein that great a piece - or at least consistently great - but it was crucially important in my development. The opera premiered on my 21st birthday (I wasn't there), and I bought the Tomato recording about a year later, sometime in 1977-78. It was my first year of grad school, I had put my undergrad years behind me, and I was ready to embark on something new. You know what a deep impact new music encountered at that age can have. I never liked all of Einstein, was even irritated by some of it, but I wore that 4-record set down to slick vinyl wafers, trying to capture every process. What impressed me most was the difficult rhythmic patterns that Glass's technique made available - and, trying to play through the keyboard parts in the score, they seem even more brain-twisting than I realized - and also the chromatic voice-leading among his harmonies. The "Bed" scene instilled in me a new conception of harmony that I use to this day. As I've reported before, years ago I had the opportunity to interview Phil in public, and told him that I was still trying to compose the "Bed" scene from Einstein. He replied, "So am I."

So I think it's only recently that a course in the analysis of minimalism has really become viable. I did receive a score of Dennis Johnson's groundbreaking piano piece November, by the way, and with that, the score to The Well-Tuned Piano, the Boosey and Hawkes Steve Reich scores, Riley's early string quartet pieces available from his web site, and what Phil Glass has now released, I think I can cover the early part of the movement. (Maybe we'll try to dissect some Charlemagne Palestine by ear; he was pretty elusive when I quizzed him about scores.) Of course, some early minimalism is too transparent to be analyzed in any conventional sense. I'm not going to hand out the score to Music in Fifths to pore over a pattern that can be easily grasped in a minute or two. At the Music and Minimalism Conference in Wales last August, William Lake presented a thorough analysis of Riley's In C, but making a larger statement about the work than the obvious one required more analytical prestidigitation than I can expect of my undergrads.

But I do think there are secrets of rhythm to be teased out from Einstein, a clear structure to be charted in Music for 18 Musicians and Octet, and afterward we'll move on to some Phill Niblock frequency charts, John Adams's Phrygian Gates, Duckworth's Blue Rhythms, Lois Vierk's Go Guitars, John Luther Adams's Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing, Peter Garland's Jornada del Muerto, and so on. Student enthusiasm has already been apparent. And this will all help me toward not only the book I'm writing, but the minimalism conference I'm directing with David MacIntire next year.

And by the way, Einstein: not a dynamic marking in the entire score.

[UPDATED] Thursday night, March 6, at 7:30 the amazing University of Kentucky Percussion Ensemble will play my Snake Dance No. 2 at the SCFA Recital Hall there in Lexington. The program also includes works by Jay Batzner, Lou Harrison, David Crowell, Russell Peck, and Paul Lansky. I've head these guys do it, and though they're young, they're incredible. (I've also been thinking about what a great place to live Lexington seemed. I was treated to lunch in a huge natural food coop where everything was great, and there were some lovely bars and restaurants. We on the coasts think of flyover country as pretty deadly, but there are some amazing pockets of liberalism, enlightenment, and good living, and Lexington was one of them. Plus, during the Kentucky Derby, Maker's Mark sells bottled mint juleps. Those truly are deadly.)

The following night at 8:30, Friday March 7, pianists Sarah Cahill and Joseph Kubera play at Roulette in New York, 20 Greene Street. It's a largely Terry Riley program, filled in with pieces by Ingram Marshall, Michael Byron, and my own On Reading Emerson, which Sarah plays beautifully on our new CD Private Dances.

My new electric guitar quartet Composure, on which the ink would still be wet if I still composed in pen, is premiering in Montreal April 4 at the Voyages: Montreal-New York festival, organized by the tireless Tim Brady.

Rodney Lister plans to include my Long Night for three pianos and Paris Intermezzo for toy piano on a program at Boston University on April 11.

On May 6, the Bard College Chamber Singers and Symphonic Chorus, conducted by my friend James Bagwell, will perform my Transcendental Sonnets at Bard's Fisher Center, only the second time the work has been done.

However, the Relache ensemble's May performances of my suite The Planets have been postponed to the following fall, though we'll still be recording the work for the Meyer Media label this summer. Mmm... think that's it for the forseeable future.

UPDATE: Heavens, forgot the most important of all. On May 9, Williams College is offering the American premiere of my piano concerto Sunken City.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog