main: January 2008 Archives

Given everything else, including a return to teaching after 13 months, I haven't been able to keep track of performances of my music lately. This Saturday, February 2, the wonderful Sarah Cahill is playing my On Reading Emerson at the Berkeley Arts Festival, along with works by Terry Riley, Stephen Blumberg, and others. "The new Arts Festival location is on Shattuck Avenue in downtown Berkeley. Details TBA at www.berkeleyartsfestival.com." The Relache ensemble played "Venus" from The Planets (mine, not Holst's) as background for a silent film this week, and I ran across a reference to a performance of Private Dances that I didn't know about. I mention all this largely because my blog is the easiest place for me to keep all my résumé items in case I ever redo my résumé again. Please drop me a line if you play something, but feel free to download it from my web site and play it!

UPDATE: Sarah adds:

Thanks for mentioning the concert, Kyle. Along with your On Reading Emerson, I'm playing the premiere of Evan Ziporyn's solo piano arrangement of Colin McPhee's Balinese Ceremonial Music, Peter Garland's Waves Breaking on Rocks (2003), Stephen Blumberg's Numina (2007), Terry Riley's Fandango on the Heaven Ladder (1994), and the U.S. premieres of three of Mamoru Fujieda's new Patterns of Plants, which have only been played on clavichord in Tokyo so far.

UPDATE: Pianist Mabel Kwan has contacted me to let me know that that was her performance of Private Dances at the Heaven Gallery in Chicago on January 27. And she's also playing On Reading Emerson in Lexington! Very nice, because I consider Chicago a second home town, and I don't think any of my music had been heard there since the mid-'80s.

Next week I'll have a short residency at the University of Kentucky at Lexington. Of public interest is that on Friday, Feb. 8, at 3:30 I'm giving the Rey M. Longyear Musicology Lecture, in honor of a well-known scholar in Classical and Romantic music, endowed by his widow. That's at the Niles Gallery of the Lucille Little Fine Arts Library. Later that evening at 7:30, there will be a concert of my music organized by grad-student percussionist Andy Bliss. He's premiering a vibraphone solo I wrote for him titled Olana, and his group will play my Snake Dance No. 2, Last Chance Sonata, and On Reading Emerson. I may play a couple of tunes myself.

Longyear was author of the first music history textbook I read in college, and I get a big kick out of being asked to give this lecture. Aside from close association with my medieval history professor Ted Karp in grad school, and an admittedly fanatical interest in historical minutiae, I don't have any musicological training. I escaped taking the required bibliography course. Wiley Hitchcock kidded me about the number of footnotes in my American Music history that read, "Communication to author" - meaning that, instead of sourcing reference works, I just called up composers for the information I needed. I find it humorous and generous that so many musicologists have been willing to consider me one of their ilk, and even quote me in their books - especially given how many composers have not wanted to consider me a composer. I was even hired at Bard as a musicologist. You train for something your whole life, and you have all this ambition and anxiety about "making it," and meanwhile you pick up a hobby, in which, were you to fail abjectly, you would simply shrug; and then the hobby takes off, and it's a very funny feeling. And so in honor of the occasion this amateur, "Sunday" musicologist will, for the first time, give a lecture about musicology itself. What a blast.

This long, long, 3800-word-plus blog entry is actually the paper on Morton Feldman I presented Sunday morning at the Seattle Art Museum, amid excellent papers by Elena Dubinets and Alex Ross. I could maybe have stuck it in an academic journal where 20 people would see it, and then I'd have a new line on my résumé:

****************

The difficulty of assessing Morton Feldman's impact is that it is so pervasive. Music has by now been so changed by people who were changed by people who were changed by Feldman that I think it would be difficult to trace the various streams of his influence back to their source. Musically, we live in a post-Feldman age, and I am certainly conscious of being a post-Feldman composer. Things are done now that were not done before Feldman gave us precedents. There is music before and after Monteverdi, and before and after Beethoven, and before and after Stravinsky, and I would not be surprised to find that poeple someday talk about music before and after Feldman.

I attended the first June in Buffalo festival, in 1975, of which Feldman was the director. That first year, the featured composers, besides himself, were his friends John Cage, Christian Wolff, and Earle Brown. I am old enough to well remember what our collective student impression of Feldman was before that festival. He was Cage's quirky sidekick. His pieces to that point had been fairly brief. We understood that they were intuitively written, but still they seemed like special instances of Cagean chance composition. Feldman didn't strictly use chance, but still he scattered his notes here and there with a kind of abandon. Sometimes chance entered into it, as when he wrote on graph paper, and simply indicated the number of pitches to be used in each register. In Cage's writings, Feldman was always good for a bon mot or two.

But that summer, in June 1975, Feldman changed before our eyes. He played us a recording of a work that to my knowledge has still never been commercially recorded: The Swallows of Salangan. It was for chorus and orchestra, maybe 20 minutes long. It was the first Feldman work I'd heard in which his ideas were extended to a perception-stretching duration and saturation. I wonder how many of us realized, while listening to that recording, that Feldman had entered new territory: all of us, I imagine.

Also, at about that time, the recording of Feldman's Rothko Chapel had just appeared on Odyssey. Perhaps we first heard the recording at the festival, I can't remember. The dense tone clusters for chorus, and the fragmentary viola lines, in that piece fit in with the atomized Cagean aesthetic - but not so the repeating four-note motif in the vibraphone at the end, or the Ravellian viola melody that hovered over it. It was the first time any of us had heard Feldman step entirely out of Cage's world into a new one all his own.

I imagine I speak for many of us at that festival when I say that we went there to see John Cage in person. We left wondering if Morton Feldman had invented a new way to compose.

And this was before Feldman had written any of his superlong pieces. The next time I saw Feldman was around 1978 or '9, when he came to Chicago and played Why Patterns? He sat at the piano, side-saddle - I wonder if maybe his stomach wouldn't conveniently let him reach the keyboard - and meditatively played his notes, one finger at a time. That was a lesson not only in musical continuity, but in a new performance paradigm. In addition, in the closing ostinatos of Rothko Chapel and the startling final pages of Why Patterns?, where the three instruments suddenly fall into a synchronized 3/8 meter, Feldman had created a new way to close a piece: the ending that starkly contradicts the rest of the piece, bracketing the piece's underlying premises as contingent, and seemingly opening a door for the listener to leave through. Along with the dramatic and unanticipated cessation of an early Philip Glass piece, it was one of the two great, seductive framing concepts that the late 20th century came up with.

****************

Out of this quiet, speciously modest music that we so underestimated at first came a number of remarkable changes that slowly shook the music world.

One change Feldman initiated was achieved simply by putting the words "as soft as possible" on a score, with no other dynamic markings following it. It takes an effort at this point to remember the extent to which the '60s and '70s were the era of having to do everything in every piece. One showed one's ambition by the range of one's music, and lack of ambition was the unforgivable sin. The operative model for the time was Stockhausen, and Stockhausen's serial technique was designed to reach every extreme within every work. Serial technique itself was a "mediation" between extremes, and the extremes had to be there. John Cage had a slightly different model according to which music was like life, inclusive of everything. Music was noisy back then. The easiest way to get applause was loud brass climaxes, and everyone who could afford them had them.

Then along came Feldman writing pieces with only one dymanic level. Until that summer in 1975, it seemed like a humorous affectation, a Satie-esque forfeiture of the ambition we were all assumed to share. Later we would come to reinterpret it as a trademark, and as a potential survival strategy in a world overcrowded with composers. When everybody does everything in every piece, when every symphony contains an entire universe as Mahler prescribed, then all music sounds more or less alike. Like Van Gogh, who quietly boasted that he had made the sunflower his own, Feldman had marked off pianissimo as his territory.

It is such a simple progression that one could miss the connection, but soon afterward composers started setting limits to their territory. The minimalists, who were very aware of Feldman, stripped down to just a few pitches. Lois Vierk and Mary Jane Leach started making pieces that were all one timbre: five guitars, or eight bass clarinets. John Luther Adams made pieces that were all C-major scale. Glenn Branca wrote music for guitar orchestras. One composer worked with computerized speech sounds, one with multicultural collage, one with bowed piano, one with the sounds of bicycles, and so on. It was almost humorous the extent to which, in the 1980s, composers in New York cultivated their niches and avoided stepping on each others' toes. To make a piece that only explored one aspect of music was a logical extension of minimalism, but the variety of types of limitations people came up with reveals that Feldman was often the more profound impetus. Feldman didn't so much inspire minimalism as he inspired postminimalism. Perhaps it was partly a response to the difficulty of creating an artistic identity in the crowded Manhattan scene, but it was partly OK because Feldman had done it.

Stockhausen once told Feldman, "Your music could be a moment in my music," but it was Feldman who had the last laugh. His monochrome music relegated Stockhausen's panoramas to an earlier historical era.

Second contribution: Where Feldman eventually compensated for his lack of volume, of course, was in his excess of length. By writing works that were 90 minutes long, four hours long, six hours long (as I've written elsewhere),

he reclaimed for the disspirited modern composer a sustainable measure of magnificent ambition, a pride in occupying an audience's time. Quietly but vehemently he asserted for all of us that new music is worth sitting still for, practicalities be damned.

I was just in Brussels visiting Charlemagne Palestine, and Charlemagne credits the minimalists as having inspired the length of Feldman's late works. Charlemagne played a role in bringing minimalism to Feldman's attention in the '60s, and he notes that it was after the all-night concerts that he and Terry Riley performed, and the three- and four-hour pieces of Philip Glass, that the length of Feldman's pieces started to expand.

This sounds entirely plausible. But the length had a different effect in Feldman's music. The four-hour minimalist performances were loud and could be walked in and out of without missing much. There was a pop music aspect to them that later turned into ambient music. Feldman's quiet, intense music with its hesitant momentum did not allow one to turn away, or to go get a drink, or make comments to one's neighbor. It demanded hours of careful attentiveness, and even worse, of a careful stillness that wouldn't disturb the music. That kind of audacity impresses people. It has often been noted now, that listeners are more willing to be generous to a long piece than to a short one, and to more easily assume that the long piece is more profound.

Luckily, not many young composers have imitated Feldman in the area of length, but that doesn't matter. His gesture alone increased the prestige of our artform in despondent times. Just when it seemed least possible, he gave music its Monet Water Lilies, its Diego Rivera murals.

Third contribution: Feldman reintroduced intuition into the compositional discourse, and restored its respectability. In the 1950s and '60s, aleatory techniques, serial techniques, and the gradual processes of minimalism were all objective methods meant to grant some new kind of validity to the music of the 1950s and '60s. To this extent, Cage, Babbitt, and Reich were on the same track, and Feldman on a very different track, one which eventually liberated hundreds of us. One of the most important stories in 20th-century music is the famous one in which Cage asked the young Feldman how one of his pieces was written. Feldman weakly replied that he didn't know how it was written, and Cage jumped up and down squealing like a monkey and shouting, "Isn't that wonderful! It's so beautiful, and he doesn't know how he did it." That story alone is enough to mark the private onset of a new historical era.

It was not simply the return of intuition in the middle of a period of formalist structuralism. For centuries before the 20th century, music had been an exercise of intuition within the framework of a tonal system that was crafted and guaranteed to restrain its excesses. There followed a brief period of completely unfettered intuition, and by all accounts - including Alex Ross's in The Rest Is Noise - it was apparently pretty scary: the period of free atonality in the 1910s that climaxed in Schoenberg's Erwartung. Schoenberg came up with the 12-tone row, Scriabin came up with his own harmonic system, Bartok came up with the axis system and golden sections, Stravinsky reinhabited old tonal structures, Hindemith rediscovered the harmonic series, and everyone rushed to fill the void opened up by this frightening new freedom.

In the midst of all this, Feldman recreated the paradigm within which intuition could be given full sway without going berserk. Within the quasi-minimalism of "as soft as possible" and only one type of rhythm per piece, the composer's intuition could go wild without getting out of bounds or wandering too far from the guiding spirit of the piece. The change sounds like a simple one, but its consequences were profound. The thinking went from, "Your intuition is limited by the musical system within which you're working," to, "Your intuition is limited by the range of materials you've agreed to work within." For me, this is virtually a definition of postminimalism, which should possibly be called post-Feldmanism, though I think it inherited tedencies from both minimalism and Feldman, along with other styles. For the first time, an enormous range of composers, from atonalists to tonalists, instrumental improvisers to laptop performers, feel free to work outside the idea of a particular musical language and to do so by intuition and feel. In a way Feldman completed what one might call the aborted musical revolution of the 1910s free-atonal years, granting us freedom from syntax or system and showing us how to use it, how to husband our resources in an open environment.

One of my favorite stories Feldman liked to tell was of Marcel Duchamp visiting an art class in San Francisco, where he saw a young man wildly painting away. Duchamp went over and asked, "What are you doing?" The young man said, "I don't know what the fuck I'm doing!" And Duchamp patted him on the back and said, "Keep up the good work." In music, it was Feldman, more than anyone else, who gave us permission not to know what the fuck we were doing.

Fourth contribution: The last area I want to mention is that of notation, in which Feldman's contribution was a little more insidious. In his notation, Feldman rammed with his full force against one of the great sacred cows of the late 20th-century composing world: professionalism. Many, many composers today, and especially those who teach or who get orchestral performances, are obsessed with the notion of professionalism. The imparting of professionalism is how a composition professor justifies his or her position in academia alongside the more easily validated fields of the sciences and social sciences. And the essence of compositional professionalism is notation. Composers in academia, myself included, constantly harp on students to make their notation as simple and clear as possible, to line the notes up right, to avoid ambiguities and complexities that have no effect on the sound.

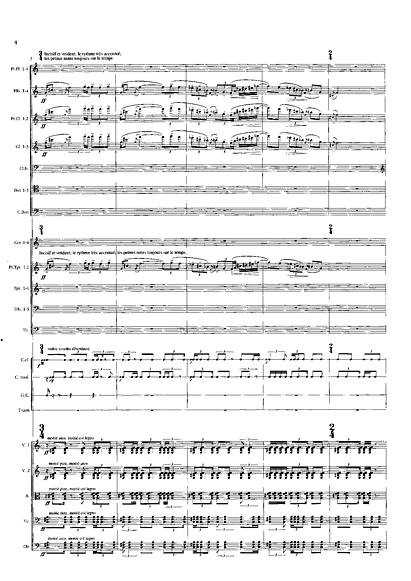

Within this atmosphere, the peculiar and ambiguous notation of Feldman's late music constitutes a deliberate act of civil disobedience. Take a look at this opening passage of Crippled Symmetry: the three instruments measures are lined up as though this were a conventional score, yet neither the meters nor even the repeat signs are aligned:

If you read down to the end of the page, the length of the flute part in whole notes is 22.3125; the length of the vibraphone part is 32.8125; and that of the piano part is 54.75, so that these three parts can't stay on the same page or be even remotely synchronized. This inequality continues to the end of the piece. There are basically three different pieces here, of different lengths, to be played at the same time. There are also measures notated with ever-so-slightly different rhythms that would be nearly impossible to differentiate in performance.

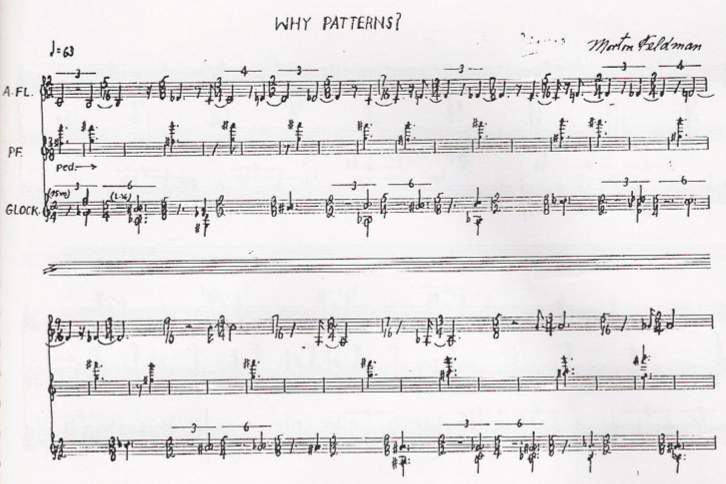

An even more aggravating example is Why Patterns?:

For long passages in this piece, the flute part is notated with every note beginning just before a bar line - even though the three instruments are not synchronized, nor is there any audible pulse against which these anacruses can be heard. One is struck by an ever-changing rhythmic complexity that goes on inside the performer's head, with an imperceptible downbeat in the middle of each note, though all the listener hears is basically whole notes separated by rests. Also notice one of Feldman's favorite rhythms in this piece: two dotted half notes in a 5/4 measure with a "2" over it, notated more irrationally than it needs to be.

Feldman liked to talk about the psychological effect that notation had on a performer. By notating those almost identical rhythms differently, or by adding a tied-over 16th-note in a context with no pulse to hear it against, he altered what the performer was thinking while playing, in order (one has to argue) to elicit a certain hesitant quality of nuance that the notation, strictly speaking, does not exactly mandate. I don't know of a composition teacher, including myself, who wouldn't throw a fit if a student brought in a piece notated this way. It flouts every professional orthodoxy of notating music, which is supposed to aim for maximum simplicity and consistency, make the notation fit the sound as closely as possible, and avoid complications that don't affect the result. Quite the contrary, Feldman's notation distances the performer from the notated page, and doesn't allow for the kind of facile sight-reading that is the core paradigm of classical music-making. Any composition teacher, faced with such a page, would immediately protest, "You can't do that." But Feldman did it, and it resulted in music too beautiful to argue with.

Feldman's notational style flouts two sacred principles of compositional pedagogy: professionalism and efficiency, which are closely related. Notation is supposed to be efficient, so as not to waste the performer's time. The underlying conceit is that time equals money, there are a lot of other composers waiting to be played, and you must get across your intentions to the performer in the quickest possible manner, so that they can get your piece out of the way and get on to the next rehearsal.

But I love what the author John Ralston Saul says about efficiency. We consider efficiency an automatically good thing in this society, but in reality, efficiency is only appropriate to things that are ultimately unimportant. We want our garbage taken out efficiently, we want our drivers' licenses renewed efficiently, but someone who advocated efficient child-rearing - eliciting maximum good behavior for a minimum of parental care - would be a beast. In the same way, Feldman's notation drives home a principle that we forget at our peril: that, however necessary the evil may sometimes be, efficiency in the pursuit of music-making is no virtue. Feldman's notation requires more care to decipher than would seem to be necessary. His passages of repetition continue without adding any new information. The very length of his late works, especially in light of the sparse content of some of them, takes its own arrogant time to get its points across.

Some of his greatest effects take an inordinately long time to achieve, a time more like that of real-life experiences than what we think of as musical time: for instance, the eternity in For Philip Guston in which the music strips down to four pitches within a minor third for a solid 25 minutes, and then suddenly spreads across the entire range of the keyboard in glorious C major. Similarly, when I heard the Flux Quartet play Feldman's String Quartet II, a mysterious kind of hush fell over the audience around 10:30, four and a half hours into the performance, and the last hour and a half of the performance seemed a kind of collective ecstasy. A more efficient composer might have skipped the first four and a half hours and given us only the ecstatic part, but it wouldn't have worked. Feldman knew that in order to enter the highest altitudes of artistic experience requires a surfeit of care and attention unjustifiable in ordinary terms.

Thus in his music and even more explicitly in his writing, Feldman drew our focus to something most of us try to avoid noticing: the dual and contradictory nature of the composer in modern society, as both artist and professional. A professional learns his craft, applies what he has been taught, conforms to the standards of the profession, knows how to work to order, and can guarantee in advance a satisfactory result. An artist scorns what can be taught, tries things that have never been done before and seem impossible, takes risks that may very well fail, but revivifies society by enlarging and rearranging our perspective.

Every composer who successfully brings a piece to performance might be called a professional, and every composer who creates something that didn't exist before might be called an artist. But on the long continuum from John Williams to Harry Partch, it seems undeniable that there are some composers more professional than artist, and others more artist than professional. Feldman sometimes writes as though the two are mutually exclusive. But the professional part of being a composer is pretty much the part that can be taught, and thus Feldman was a crucial counterforce to the hurricane wind of our music pedagogy that sometimes pushes young composers so hard to become professionals that they forget, or never learn, that the job requires hysterical off-the-wall creativity as well. In one interview Feldman candidly admitted,

You know, there's not one thing that I ever learned in the past that I could actually apply to my music. Nobody ever helped me. Any insight I had in the past does not reflect on anything I'm trying to do. I have no models to use. What I have to use is another tradition: how to notate.

In a more famous article, he wrote,

In music, when you do something new, something original, you're an amateur. Your imitators: these are the professionals. It is these imitators who are interested not in what the artist did, but the means he used to do it. The freedom of the artist is boring to [the imitator] because in freedom he cannot reenact the role of the artist.

At the same time, it is pleasantly inconsistent to note that Feldman liked passing out the occasional bit of professional advice. I remember him saying that a composer should write pieces for a variety of solo, duo, quartet, quintet, and so on, combinations, to build up a varied portfolio so as to be ready for a wide range of performance opportunities - a piece of advice that would have done little artistically for Chopin or Harry Partch. But Feldman also had a standing offer to his students that he would buy dinner each semester for the student who could come up with the worst orchestration. No one ever won, he said, because the worse orchestrations they tried to think of, the more creative they got. In other words, the more they failed professionally, the more they succeeded artistically.

All this makes Feldman a deliciously dangerous role model. Practically any advice a teacher gives a student about notation, the latter can pull out a Feldman score and say, "But look at this...." It was delightful witnessing the inevitable rise of Feldman's reputation after he died. In the 80s and 90s I visited school after school where the students were obsessed with Feldman, where the music faculty fiercely resisted taking Feldman seriously, but eventually had to surrender because the student interest was just too universal and fanatical. Feldmania was a flood tide that washed across the country, all the more irresistible because there was no central principle to it, no theory, nothing one could disprove. Feldman's musical results, and only his musical results, spoke for themselves.

Feldman changed what composers think, how we feel about what we think, and how we are allowed to defend our choices. He gave us a sword with which to shatter the thick shields of rationalism, professionalism, and conventional wisdom. But he also taught us that the worst enemies of creativity lie not only outside, but within us. One of his favorite assignments for student composers was, "Write a piece that goes against everything you believe." Many a young composer, fulfilling that assignment, realized with chagrin that he had just completed his best work.

Alex Ross got a photo of the official poster for our Seattle Chamber Players match-up:

I have to say I agree with the SCP's decision not to allow photographers into the mud-wrestling event.

SEATTLE - What a fantastic and warm group of artists we got to Seattle for a three-day love- and music-fest. I forget how good a concert can be when I pick the composers myself. Plus, I met a lot of younger composers I'd only heard of. More about all that later when I'm not running through snow for the airport. For now:

Judd Greenstein, Nico Muhly, Alexandra Gardner (Alex Ross's crowd):

William Brittelle looking totally characteristic, Anna Clyne:

Elena Dubinets and Bill Brittelle in background, and the Rossmeister, captured with sparks coming out of his brain:

Janice Giteck and Stewart Demspter

Bill Duckworth and John Adams together again, Arthur Sabatini mediating, with DJ Tamara to the side and Nora Farrell invisibly in there somewhere:

Max Giteck-Duykers with wife Rebecca, local young composer Lena, and composer-mother Janice:

Trimpin, John Shaw of Utopian Turtletop fame, me, and Elodie Lauten:

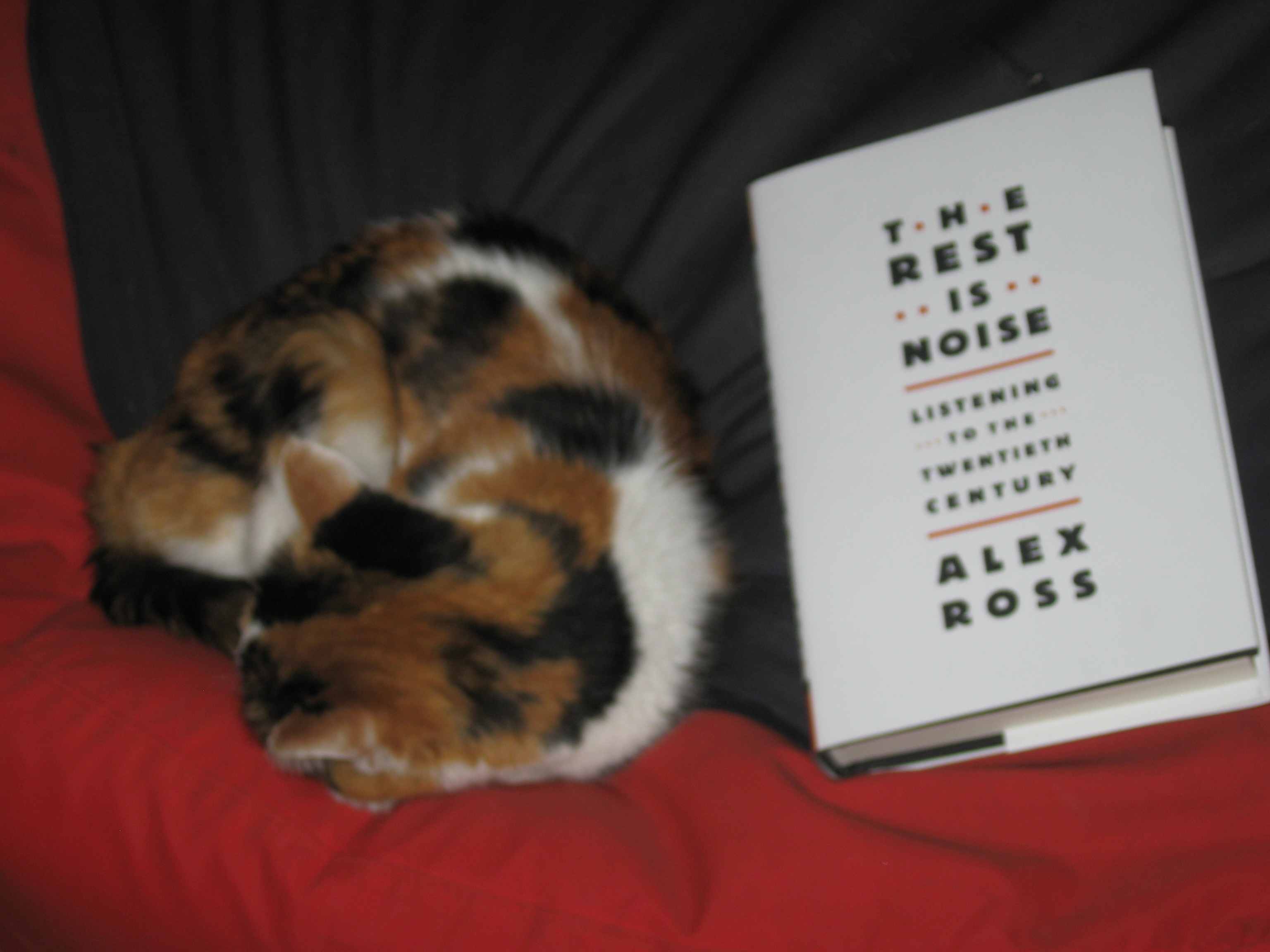

And inevitably, when we got to the closing party at cellist David Sabee's house, one found the host's cat curled up in the usual posture. I'm sure that the fact that he's sound asleep is no commentary; probably just finished reading the last chapter and is resting contentedly:

Among the other composers, Eve Beglarian couldn't be there, and I don't know where Mason Bates was whenever I had my camera out. But I'll tell you the photo I missed, which would have spelled a major upheaval in the the blogosphere. One morning I walked into my hotel and met Alex Ross coming out of the hotel gym all sweaty in his running shorts. Had I had my camera out and ready, it would have meant the end of classical music as we know it.

SEATTLE - A couple of people requested that I blog my introduction to last night's Icrebreaker concert with the Seattle Chamber Players. The program consisted of:

Kyle Gann: Kierkegaard, Walking

Elodie Lauten: Scene from 0.02 (the Two-Cents Opera)

Janice Giteck: Ishi

John Luther Adams: The Light Within

Eve Beglarian: Robin Redbreast

William Duckworth and Nora Farrell: Cathedral

The previous evening we had heard music by younger composers, curated by Alex Ross: Alexandra Gardner, Anna Clyne, Mason Bates, Judd Greenstein, Max Giteck-Duykers, Nico Muhly, William Britelle.

********************

The title of tonight's concert is "Classics of Downtown," which may be mystifying to some of you, so I'm going to try and provide some background to what that means.

In 1960, composers La Monte Young and Richard Maxfield persuaded Yoko Ono to let them use her loft in Downtown Manhattan for a concert series of rather bizarre and unusual musical performances. Now, Yoko Ono was at the time a failed pianist, and anything but famous: this was seven years before she met John Lennon, several years before anyone had heard of John Lennon. The music in these concerts consisted of things like people making sounds by hitting their heads on the wall, setting fire to their sheet music, and playing notes as motionlessly as possible for a long time. This was a ridiculously different music from the kinds of conventional chamber and orchestra music that most composers were involved with at the time, and it spread to other spaces in lower Manhattan, other people's lofts, the Judson Church, and various abandoned industrial spaces. Since before this time almost all performances of music had taken place uptown in the area where Lincoln Center would soon be built, this different music became referred to as Downtown music.

Downtown music remained a rather underground phenomenon for more than a decade. But the part of Downtown music that was occupied with drones and slowly changing harmonies and melodies became known as minimalism, and in 1974, recordings by Steve Reich and Philip Glass brought minimalism to worldwide attention. The growing popularity of this music challenged and eventually shattered the image most people had of a single, monolithic history of contemporary music.

In 1979, the Kitchen in New York presented a festival called New Music New York, featuring minimalist music by several composers along with other new streams as well. This was the most visible sign that there had been a significant mutiny within the world of contemporary music. Several dozen composers had decided that the classical music train was in tremendous danger of jumping the track - if, indeed, it hadn't done so already. The contemporary music of the time was largely abstract, dissonant, and difficult to understand, and had created its own bad reputation with audiences. The classical music that people still liked was in danger of becoming irrelevant, senile, a ghost from another century. New Music New York showcased composers whose music was hip, attractive, sometimes provocative, but not difficult to grasp, and that abandoned many of the conventions of classical music.

And so, buoyed by the public success of minimalist music, these two dozen or more composers broke off and declared themselves a new genre, separate from classical music or jazz or rock. Because of that festival's title, the music was called "new music," and remained so for the duration of the New Music America festival that grew out of the original festival, from 1979 to 1990. The festival was overseen by a loose organization called the New Music Alliance. The popular minimalism of Reich and Glass was the public face of this new music, but it was only the tip of the iceberg. New music was not so much a style as a specific collection of people who shared a dissatisfaction with the rigid and narrow mandates that had overtaken the world of contemporary music.

Of course, the term "new music" was so vague as to guarantee its own eventual demise, but a vague term was what was needed. Anything more specific would have pushed the music in a specific direction, and no one knew where it wanted to go yet, nor whether it even particularly wanted to go anywhere. The term "experimental music" had already been tried, and some didn't like it. In New York City, new music was also known as Downtown music, because all the spaces this music was played in were south of 20th Street. It didn't matter where you were from, Brooklyn, Birmingham, Alabama, or Fargo, North Dakota - if, when you performed in New York, it was at a Downtown space, you were a Downtown composer. That term was in frequent use from the mid-'60s to almost the end of the century.

Like new music, Downtown music was a specific group of people and a specific set of performance spaces. It is arguable whether a person could have been a Downtown composer in isolation. If you were a Downtown composer, you went to the concerts. You knew the composers. Many a time I went to a concert in Amsterdam or Paris or San Francisco, and saw the same people at intermission whom I was used to seeing at performance spaces like Roulette and the Knitting Factory in New York. No corner of the earth was far enough away to escape the 400 or so composers and improvising musicians who made up this scene.

Tonight's concert is devoted to composers who were part of that scene, and whose music would have been called in the 1980s new music, or Downtown music, and that today might be called "postclassical" music. Calling us "classics," I think, is to suggest that we are all, as one might say, "of a certain age," and have been around too long to be considered "emerging" composers like the ones you heard last night. But this music so split itself off from classical music that in many respects the scene itself is still emerging, as a genre of music that is neither classical, pop, nor jazz, somewhat in between but not entirely that either. Since the cohesion of this scene was at least as much social as defined by any inherent musical principles, I want to emphasize in my descriptions the kind of connections each composer had to the scene.

Elodie Lauten came to Manhattan from France in 1970, lived and performed with the poet Allen Ginsburg, shaved her head before it was hip, studied with the reclusive minimalist guru La Monte Young, interviewed Mick Jagger, and performed as singer for a rock band called Flaming Youth. In 1986 she put out a recording of a dark, mysterious feminist opera The Death of Don Juan, which seemed like the logical next step after minimalism, and which is just now being reissued on CD. I reviewed The Death of Don Juan enthusiastically in the Chicago Reader, and when I got a job at the Village Voice later that year, Elodie was one of the first people I wrote about and the first people I looked up. She has continued to come out with a new theater work every few years, some of them with Baroque music ensemble, some incorporating Broadway and gospel style, but all suffused with mysticism. She also performs as an improviser, using a system of correspondences between harmonies and nature that she calls the Gaia Matrix. One of her operas I reviewed, whose title was simply Existence, had no humans on stage, just a softly mumbling television.

Janice Giteck was more reclusive, and she lived far, far away in this place New Yorkers had barely heard of, called Seattle. Though she studied in France and at one time seemed destined for a more conventional and celebrated classical music career, she would disappear from the composing world from time to time, to work with schizophrenia patients and AIDS victims. But Foster Reed at the New Albion label put out a recording of Janice's music, and the Relache ensemble in Philadelphia performed her music, and I started writing about her, so gradually she materialized into the new music scene.

Some of you may know the music of the famous accordion composer Pauline Oliveros. If you could imagine someone even more devoted to cosmic harmony than Oliveros, it would be Elodie Lauten, and if you could imagine someone even more devoted to universal harmony than Elodie, it would be Janice Giteck. Those of you who were here last night heard that Janice's son Max also writes music, which is a good reminder that children often pick up their parents' bad habits. So be careful.

John Luther Adams I first encountered from a vinyl record called Songbird Songs, and made a mental note that he was not the same John Adams who wrote Shaker Loops and Nixon in China. John lives in Fairbanks, Alaska, and writes his music very much about the Alaskan landscape, and at the time I became aware of him, he was making a living more as an environmentalist and activist than as a musician. He and I started corresponding, and somehow we figured out that we were both making connections in the Chicago airport on the same day, so we met there for lunch. Since then, I wrote the introduction to John's book of essays Winter Music, he wrote the liner notes for my CD Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and the talks we've shared on long walks have sparked some of the great aesthetic realizations of my life. John is one of the few new music figures who has had a career writing music for orchestra. One of his greatest works, In the White Silence, is 75 minutes for orchestra, with not a single sharp or flat. That's how white Alaska is.

Eve Beglarian had been a composer of complex 12-tone music at Princeton and Columbia. But she had her own individual mutiny, and was programmed on a festival in New York by my friends David First and Kitty Brazelton, where I started writing about her. There's a wonderful story Eve tells about studying at Columbia. She was writing a piece that started out with only one pitch over and over, D. Her teacher couldn't stand the idea, but allowed her to go ahead on the condition that when a second pitch came in, it would be E-flat. "No," she said, "it's going to be F-sharp." He threw up his hands, and that was the definitive moment of Eve's separation from the classical music world. You can't get a picture of the musical situation of the 1980s until you can understand that the difference between a half-step and a major third meant the difference between remaining in the mainstream and becoming an outsider.

For years Eve made her living making audio backgrounds for the cassette version of Stephen King novels. She is technically sophisticated, and absolutely irrepressible. Commissioned to write a religious piece for pipe organ and tape called Wonder Counselor, she wanted to make it as joyous as possible, and filled the tape part with bird songs, ocean waves, and a couple having orgasms. There is, however, an alternate version for church performance.

Bill Duckworth and I had both studied with Ben Johnston, though in different decades. I first heard Bill's music on the second New Music America festival in Minneapolis in 1980, when Neely Bruce played his Time Curve Preludes there. Seven years later I met Bill at New Music America in Philadelphia, courtesy of the Relache ensemble. He brought me to Bucknell University, where he taught, and where I became an adjunct professor.

A real senior statesman for the second-generation minimalists, which is to say the postminimalists who were doing something very different from minimalism but derived from it, Bill was a master at large groups of short movements whose movements were linked together in ingenious ways. In the mid-1990s he became intrigued by the idea of internet performance, and started a grand long-term project called Cathedral, which allowed improvisation and listener participation within an overarching musical structure. Thematically, Cathedral is based on five seminal moments in human history: the building of great pyramid, the groundbreaking for Chartres Cathedral, the founding of the Lakota ghost dance religion, the detonation of the first atomic bomb, and the creation of the worldwide web. Somehow, using software and hardware so sophisticated that my eyes glaze over when they starts describing it, Bill and his partner Nora Farrell can take all these improvisations and listener contributions and make them sound like something that sounds recognizably like Cathedral every time.

Finally there's me, who started out as a Chicago music critic, and called myself a Downtown musician years before the Village Voice brought me to New York. I've brought up the Relache ensemble several times. Those of us who were sort of second-generation minimalists, and didn't start our own ensembles like Glass and Reich did, didn't have a New York ensemble to play our music, so the Relache ensemble in Philadelphia adopted us. It was Joe Franklin, the visionary director of the Relache ensemble, who championed the music of Bill Duckworth, Janice Giteck, Eve Beglarian, and myself, and who organized the Music in Motion project that brought me to Seattle in 1994 for my first connection with Paul Taub, Janice Giteck, and the Seattle Chamber Players. This summer Relache is recording the 75-minute work I started during that residency.

My initial musical interest was in different tempos running at the same time. A lot of my early music was very difficult for ensemble performance, and it was really Bill Duckworth's music that taught me how to reorganize the kinds of tempo ideas I like for a chamber ensemble to handle. As a result, instead of hearing the ensemble struggle through rhythms like 7-against-9-against-11-against-13 in my piece tonight, you'll hear floating ostinatos going out of phase with each other in a much more reasonable quarter-note = 84 tempo. I've also stolen some melodic ideas from Elodie Lauten, and my music usually aims for the kind of equilibrium and serenity for which the musics of Janice Giteck and John Luther Adams are notable models.

I'm placing a rather bizarre and uncriticlike emphasis on all these personal and musical connections to counter a historical narrative about this music which has become very popular. According to this narrative, the American composers who have rebelled against the classical tradition are considered mavericks - that is, loners and nonconformists. Technically, according to the dictionary, a maverick is "an unbranded calf, cow, or steer, esp. an unbranded calf that is separated from its mother." By extension it has come to mean "a lone dissenter, as an intellectual, an artist, or a politician, who takes an independent stand apart from his or her associates."

According to the narrative, there is a consistent body of contemporary music practice, and a few maverick individuals, like Partch and Cage and Nancarrow, who have turned away from it. Among other things, this myth has been enshrined in the books American Mavericks by Susan Key and Larry Rothe and Mavericks and Other Traditions in American Music by Michael Broyles, and in the Peabody Award-winning radio series American Mavericks, for which I wrote the script (under protest at the title).

But someone observing the scene closely has to wonder: why do these so-called mavericks all know each other? Why are they so multiply connected? If they're really mavericks, really loners and nonconformists, why do their biographies criss-cross and connect at so many places? If Conlon Nancarrow was a maverick, why did he explicitly and admittedly get all of his rhythmic ideas from Henry Cowell? If John Cage was a maverick, why did he collaborate with Lou Harrison and hang out with Morton Feldman, and why do so many younger composers cite personal connections with him? Why do the names of mavericks like La Monte Young and Lou Harrison and Ben Johnston come up over and over again in the biographies of the younger new-music composers? Why do the same musical ideas, like multiple tempos and altered tunings, come up over and over again for all these mavericks who allegedly refuse to be influenced by anyone else?

The answer, of course, is that maverick is a stupidly inappropriate word. We're talking about a whole musical society of people who know each other, socialize, steal ideas from each other, influence each other, learn things from each other, bounce ideas off each other, develop musical styles and techniques collectively, just as musicians have always done for centuries. The specific ideas may be new in the history of classical music, but the types of interaction are anything but new, and anything but peculiar.

Musicologists, critics, and those who develop the musical discourse are reluctant to admit that this new music, this Downtown music, this postclassical music, is a separate musical practice that has broken away from the conventions of classical music and created its own norms. The maverick tradition they talk about is an oxymoron; these aren't "lone dissenters," they're all dissenting together. These cattle aren't off on their own, they're cattle who simply formed their own herd somewhere else. These are not calves who've been separated from their mothers: on the contrary, they're proud of their musical parentage and happy to tell you about it. These are not unbranded calves, but the brand name keeps changing: experimental, Downtown, new-music, and most recently postclassical. Each term is disliked by a number of people, and any term that distinguishes people from what is considered normative is always problematic.

The thing that excites me about tonight's concert is the opportunity it provides to think about collective aspects of creativity in a world whose thinking about art is organized around the Great Man phenomenon. Unfortunately, musicians take music history classes, and what they learn about are Great Men.

They see Chopin, but they don't see John Field, from whom Chopin stole the idea for the Nocturne.

They see Beethoven, but they don't see Hummel, whose F# minor Sonata was considered the most difficult in the world, so that Beethoven had to write the Hammerklavier to compete with it.

They see that in the 1780s Mozart and Haydn wrote the great works of the classical era, but they don't see how, in the 1770s, both of them were stuck, until they met in 1780 and started stealing ideas from each other.

There is a reluctance in our culture to admit the extent to which creativity is a collective process, the result of ideas being filtered through many minds in contact with each other. The composers you'll hear tonight are people who have been important in my own creative development. Perhaps I've been important in some of theirs. (For instance, anecdotally I can report that I once said in a newspaper that Bill Duckworth was the master of long pieces made up of short movements. His very next piece was in one long movement.) And we would be here all night if I allowed myself to mention the other 400 creative artists through whom we all share a myriad other multiply-branching connections. Perhaps you'll think of us, in contrast with last night's younger composers, as representing a particular historical era, a certain phase in the development of music after modernity. For me, tonight's concert looks like the way music history does while it's actually happening, rather than the way it looks fifty years later when the musicologists and performers have picked out the bits they like and made up stories about them. This is my story, and I'm sticking to it. So stay in the moment, and enjoy.

DJ Tamara, Trimpin, Arthur Sabatini (hotsy-totsy postmodern theorist and narrator of Bill Duckworth's Cathedral ensemble):

Elodie Lauten and John Luther Adams:

Composers Max Giteck-Duykers, Nico Muhly, Judd Greenstein, and Alexandra Gardner onstage talking to the audience:

Me and John Shaw, blogger of Utopian Turtletop:

Now will you believe we're not the same person? (I had just glimpsed the ghost of Ferruccio Busoni over the photographer's shoulder.)

I had blogged that my talk at the Icebreaker festival in Seattle tomorrow morning (Saturday) would be at 11 AM. The time has been changed to 10 AM.

As I off to the airport, I leave a reminder that Alex Ross and I will be going mano a mano in Seattle this weekend, to settle once and for all which of us can lavish more fulsome praise on the other, while each subtly trying to make his own book sound like the better read. The details about the Seattle Chamber Players' Icebreaker festival, which is hosting us, can be found at their web site. "Alex Ross and his World" day is all day Friday (tomorrow) starting at 10 AM at On the Boards, 100 W. Roy Street, and "The Parallel Universe of Kyle Gann" is Saturday, same place and time. Sunday is the showdown at which we fight to show who can describe Morton Feldman in more scintillatingly piquant terms, and then the SCP has a Feldman marathon. I'll be seeing so many old friends that I'm sure I'll end up photo-blogging the event. If you're around, come see me and get in the picture!

Some of the misinformation that goes out on Amazon.com is an afternoon's entertainment in itself. Their page for my new CD Private Dances, which officially goes on sale today, lists my son Bernard as the "conductor" for the disc. Actually, he plays bass in one piece. This is how rumors get started.

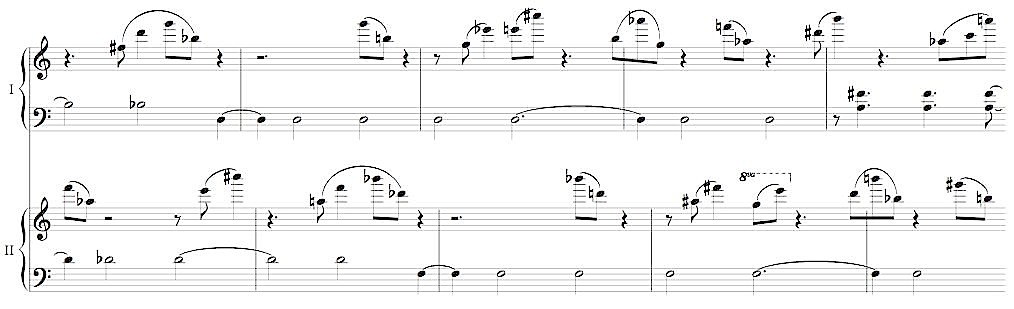

I recently had cause to mention my tempo canon for two pianos (or piano and tape), The Convent at Tepoztlan, and it occurred to me that the poor piece hadn't seen the light of day in 17 years. So I took a few spare hours and put it into Sibelius notation, which was a pain in the neck, because the two parts (performed with clicktrack) are out of kilter by a tempo ratio of 23:24. I had to input one part in an invisible 23:24 tuplet, and since Sibelius won't copy partial tuplets or paste into tuplets, there was no efficiency involved in its being a canon. (Of course, I'm still using Sibelius 2; if Sibelius 5 is improved in that respect, I'd appreciate hearing about it. I'm resisting upgrading because I don't like how long the sounds seem to take to upload in newer versions.) And since the meter is 5/4, and 5 doesn't divide into either 23 or 24, I couldn't justify measures and staves in either part. Does anyone know if true multitempo (or multi-meter) music is getting any easier in notation software?

In any case, a score to The Convent at Tepoztlan is now available. I think I might not post an mp3, since the sole recording used a tape part made with 1989 MIDI technology, and I would only get comments on its hokiness. It's an odd piece for me because the structure of the canon (pianos starting together, diverging, switching tempos, and coming back, at the canonic interval of a minor third) imposed a more audible, somewhat Bartoky architecture than I'm accustomed to use. It wasn't my first tempo canon - I wrote a slow, soft, Feldmanish one in college, at a time I'm not sure I'd even heard any Nancarrow - but I've never written one since. I'm curious as to whether my readers know of other tempo canons besides:

- the two dozen Nancarrow wrote,

- the couple I've written,

- Lou Harrison's 1941 Fugue (though per its title this may be more tempo fugue than strict canon, I can't remember and don't have the score handy),

- Jim Tenney's Spectral Canon,

- Larry Polansky's Four-Voice Canons,

- the augmentation canons in The Musical Offering,

- and the remarkable Agnus Dei from Josquin's Missa L'homme armé super voces musicales reprinted in HAM.

I remember years ago Ron Kuivila had an electronically generated piece based on the idea called Loose Canons, a title I much envied, and I also recall once a live performance by "Blue" Gene Tyranny in which material he played was echoed by a sped-up recording in real time. We should make another list! (I'm not going to count Ockeghem's Missa Prolationem, because a prolation canon and tempo canon aren't really the same thing; once Ockeghem moves into faster note values, the voices all end up at the same tempo.)

UPDATE: OK, in response to overwhelming demand from David Toub and Marc Geelhoed - come on, guys, slow down the e-mail barrage already! - I've put up an mp3. The tape part was sequenced in 1989 on old Voyetra Sequencer Plus software - anyone remember that? - with a Yamaha DX7, onto a four-track cassette recorder. Sounds like I was living in the 19th century (but at least I wasn't using Italian expression markings). The pianist is the superb Judith Gordon of Essential Music, but the recording is hardly better than the MIDI realization. Let it serve as a cautionary example, a reminder of primitive times.

Icebreaker is the name of a fantastic new-music ensemble in England, a space in Amsterdam that used to present new music and no longer does but still serves excellent food, and an annual festival presented by the Seattle Chamber Players. I can't imagine why that one word has so many new-music connotations.

In any case, the next Icebreaker festival in Seattle is in three parts: two concerts of new music curated by Alex Ross and myself, respectively, January 25 and 26; and a Morton Feldman marathon on January 27. The festival takes place at On the Boards, 100 West Roy Street. The concert I'm involved with is called "Classics of Downtown", and features music by Bill Duckworth, Elodie Lauten, Eve Beglarian, Janice Giteck, and John Luther Adams. Also a new piece of my own: Kierkegaard, Walking for flute, clarinet, violin, and cello, the best (in my opinion) of my 2007 works. (I didn't curate myself, the commission came with the gig.) I'm also speaking about my music at 10 AM on Saturday, reading from my latest book at 4:15, giving a pre-concert talk at 7 that evening, and talking about Feldman on a panel the next day between 10 AM and 1. It's a lot of talking, but I'm excited about it, and also about visiting Seattle to see so many friends, not only the composers on my concert, but Alex and some of his protègès, and the Seattle players, with whom I visited Costa Rica a few years ago. It's going to be a great weekend. Good things always happen to me in Seattle, it's a charmed location for me. I began my piece The Planets there in 1994, and wrote "Venus," which was at the time the best music I'd ever written.

On the Boards has a podcast up in which I talk about the composers and pieces on my concert. I don't even know what a podcast is, but I am now the author/performer/podcaster pf one.

And the day I return to New York I resume teaching at Bard. I've written 100 minutes of music in 13 months, and, for the first time in my life, I'm actually tired of composing. Usually I get to compose for two weeks here, six weeks there, and I'm always squeezing it in between other obligations. This was my full composing year. Believe it or not, I'm finally looking forward to waking up some morning soon and being able to do something besides put notes down on paper, or entering notes into Sibelius. I've now lived as a composer, and I know what it's like. Funny, some of the pieces wrote themselves ("Mercury" and "Uranus" from The Planets, Charing Cross), some needed revisions but clicked into place flawlessly (Kierkegaard, Walking), some I had to struggle with but after much work they came out splendid (Sunken City, Olana for vibraphone), and others were just damned hard work (my guitar quartet, "Saturn" from The Planets). I feel like it has to do with mood swings and inspiration levels, but, really, it seems to depend most on the type of piece, because one piece will zip along easily, and the next day another will bog down. The easiest pieces to write are not necessarily the best, but the hardest to write seem to lead in the most interesting and unexpected directions. For the first time in my life I am sated with composing, and ready to take a break. 2007 was the most productive year of my musical life. If you're near Seattle not this weekend but the next one, come celebrate it with me - and pick up a copy of my new CD Private Dances.

It seems like I'm writing an awful lot about European music lately, as though going to Europe focused me on a continent I hadn't paid attention to in a long time. Partly true, perhaps, but largely coincidental, I think. In any case, Michael Grossi has uploaded David Carter's elaborate MIDI realization of Kaikhosru Sorabji's Jami Symphony. The timings of the movements are as follows:

1st movement: 1:34:47 (86.81MB)

2nd movement: 19:46 (18.1MB)

3rd movement: 1:58:57 (109.91MB)

4th movement: 43:07 (39.48MB)Total: 4:36:37 (301.82 MB)

Four and a half hours: that's one long friggin' symphony. That's the Well-Tuned Piano of orchestral works. I freely admit I haven't listened to the whole thing yet, and don't know when I'll have the time, but I'm fascinated by Sorabji's music, especially given how early (late 1910s) he was working at a level of complexity unprecedented by anyone except the then-unknown Charles Ives. According to the Sorabji web site, the Jami was his Third Symphony, written between 1942 and '51. You can obtain a miniature score for £205, in case you'd like to arrange a performance with your school orchestra or something. The work contains a wordless chorus and baritone solo, realized by wordless vocal timbres in the recording. Carter's goal is to someday implement a higher-quality realization using the Vienna Symphonic Library. It's only a MIDI version, but, as Carter says, if you're my age, you're unlikely to hear an actual performance or recording of the work in your lifetime.

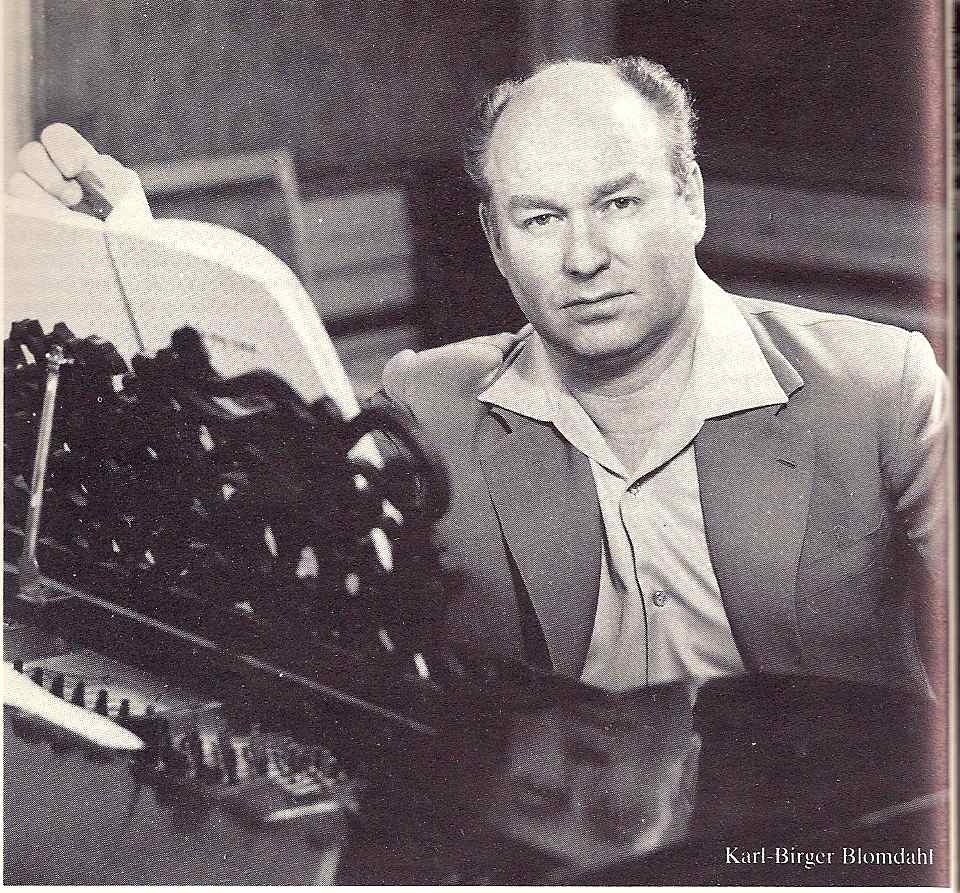

Just before leaving for Europe I chanced to pick up a vocal score of Karl-Birger Blomdahl's science fiction opera Aniara, and I've only recently had time to spend with it. I won't divulge the used bookstore where I found it, because they acquire a certain amount of modern scores from estate sales (lots of Henze and Berio lately), and I seem to be their prime buyer at the moment - though I must add that their prices seem outrageously high at times. (I've also bought scores to Brant's Angels and Devils, Riegger's Dichotomy, John Adams's Chamber Symphony, and some Henze piano music, among other things.) However, Aniara was a piece I reviewed for Fanfare back in the '80s (the 1985 Caprice recording), and when I saw the score, I knew I wouldn't resist temptation for long, so I just grabbed it. The piece made something of a splash when it premiered in 1959, got reviewed in Time magazine, and was filmed for TV in 1960. Yet today neither recording nor score seems available. Aniara struck me as one of the most engaging, and at the same time among the least pandering, of modern operas. That it and Blomdahl (1916-68, pictured below - I scanned it because I can't even find an image of him on the internet) have fallen so far off the radar screen seems unfair.

Based on an epic poem by Harry Martinson (1904-78), who I gather was one of Sweden's most important poets, and set in the year 2038, Aniara is the story of a space ship taking passengers from Earth (named Doris in the fanciful text) to Mars. In swerving to miss an asteroid the space ship is throw off course, and heads off into the infinite. Meanwhile, radio reports reveal that the Earth has been destroyed by nuclear explosions. Act I shows the passengers entertained by a kind of pop singer named Daisi Doody, who sings in a catchy kind of Swedish scat, and a comedian named Sandon, as they try to absorb the tragedy that's befallen them. Act II takes place 20 years later, the passengers having fallen into decadence and cult worship as main characters die off and the journey reaches its inevitable oblivion.

Based on an epic poem by Harry Martinson (1904-78), who I gather was one of Sweden's most important poets, and set in the year 2038, Aniara is the story of a space ship taking passengers from Earth (named Doris in the fanciful text) to Mars. In swerving to miss an asteroid the space ship is throw off course, and heads off into the infinite. Meanwhile, radio reports reveal that the Earth has been destroyed by nuclear explosions. Act I shows the passengers entertained by a kind of pop singer named Daisi Doody, who sings in a catchy kind of Swedish scat, and a comedian named Sandon, as they try to absorb the tragedy that's befallen them. Act II takes place 20 years later, the passengers having fallen into decadence and cult worship as main characters die off and the journey reaches its inevitable oblivion.

OK, it's not exactly a feel-good opera, and it's largely 12-tone to boot. But the row is a simple expanding series - C B Db Bb D A Eb Ab E G F F# - and the simplicity of that structure unites the work in clearly audible chromatic tendencies:

Consequently, the harmony always seems to be expanding or contracting, and the choral passages are among the most singable and followable in the 12-tone repertoire. Boulez would probably have pronounced this kind of technique simplistic, but it possesses the right density for music theater, not too dissimilar in this respect from Wozzeck - and, truth be told, there's something about science fiction, this "woo woo we're in outer space" feeling, that makes the discomforting 12-tone idiom ring more plausibly. In addition, the chromatic aura is cut by and blended with two other idioms. One is a kind of Swedish outer-space bebop that attends the "Yurg" cult around Daisi Doody - by which I mean that it doesn't sound like Blomdahl's trying to write bebop, only that he's created a hybrid music indebted to it. The other idiom is the electronic music used for various sequences, such as when the computer-like being Mima is transmitting images of the Earth destroying itself. This admirably smooth fusion of atonality, bebop, and electronics must have been unutterably hip in 1959, and given the recent long-lived wave of conservatism we've lived through (musically and otherwise), I have to think that if Aniara were reintroduced today as a brand-new work, within the opera world it would still seem just about as daring in its mashup of idioms as it did then: postclassical before the fact.

In fact, one of the first things I did in Europe was to visit the American expatriate composer Wayne Siegel in Aarhus, Denmark, who teaches electronic music at the Royal Conservatory. (My profile of him just appeared in Chamber Music magazine.) And Siegel played for me excerpts of his own science fiction opera, Livstegn, or "Signs of Life" (1993-94), about a scientist plunged into a personal crisis by his unexpected discovery of intelligent life on one of Jupiter's moons. Here were the same melding of live instrumentals and electronics, only instead of 12-tone, the work's background style is postminimalist. Livstegn hasn't been performed since its premiere run in 1994. It deserves revival, and an American premiere, as does its remarkably parallel distant cousin Aniara.

Why do such works get marginalized from the narratives of contemporary music? Because their composers are not from the approved countries from which excellent music is supposed to spring? I'm glad to own the vocal score to Aniara, and if I ever teach a course dealing with 12-tone technique - which has crossed my mind at times, believe it or not - I think I'd use it as a particularly clear and flexible example. And since I hate describing anything to you you can't listen to, here's an mp3 of Scenes 1 and 2.

I have only made one edit on Wikipedia since I made a big brouhaha about the site several months ago. I ran across a page titled "Cultural depictions of George Armstrong Custer," and noticed a subsection on musical references to Custer. Human nature being what it is, I rather thought a citation of my music theater work Custer and Sitting Bull might be appropriate there, and added it. It was immediately deleted, as violating the rules against self-promotion. I said "Hmph," or words to that effect, cursed myself for deigning to pay attention to that benighted web site, and moved on.

Weeks later I get a note from the person responsible for the deletion. He (or she) has restored the reference, explaining that it is better for someone besides the composer to have added it in. He had also supplied, in his text, the helpful fact that Custer and Sitting Bull was premiered in New York in 2000, and asked me to verify the accuracy of what he had written.

Now, given Wikipedia's philosophy, I am rather affronted to be appealed to to verify facts about my own career. Silly me, I had rather thought I premiered Custer and Sitting Bull in 1999 in Los Angeles, but clearly that impression is too subjective to be trusted. I have no printed reference work to footnote for the information, only my own resumé, which I could have all kinds of self-serving reasons to falsify. Perhaps I am trying to claim credit for having achieved in the 20th century innovations that didn't really occur until the 21st. And so if Wikipedia's stance is that information added by an objective party is always better than that added by a self-interested expert, then in the Wikipedia universe, Custer and Sitting Bull will have to have been premiered in New York in 2000. To ask my opinion in the matter seems like hypocrisy.

[Update below] I've been intending to write more about my European sabbatical, but I'm rather frantically composing on deadline. I have five world premieres coming up in the next several months, and two of the pieces aren't finished. Thanks to my extended leave from teaching, I wrote seven works in 2007, totaling some 85 minutes of music - not much by some people's standards, but a personal record for me. And I have two movements of The Planets to finish before school starts, so that the Relache ensemble can start practicing the entire 75-minute, ten-movement work - my own Turangalila, I like to think of it as - for their performance in Delaware in May. Also, my European trip was a lot to process: seven countries in eleven weeks, giving six concerts and ten lectures, meeting lots of composers, and hearing tons of new music. Unlike the American businessmen in novels, every American artist goes to Europe hoping to be changed. I'm not sure I was, but I did need time to think about it.

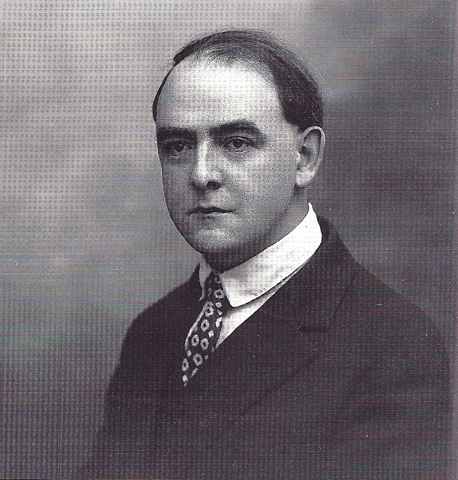

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) "the Charles Ives of Holland," and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony - considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) - received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as "the Dutch Sacre du Printemps." Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won't tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) "the Charles Ives of Holland," and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony - considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) - received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as "the Dutch Sacre du Printemps." Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won't tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

On top of the fact that he was decades ahead of his time, Vermeulen was just my kind of guy. Autodidact and too poor to buy concert tickets, he learned the repertoire by listening to orchestras play from outside the Concertgebouw, sitting in the garden. He found work as a music critic, one whose sharp and outspoken views earned him enemies and injured his chances for performance. (My apartment in Amsterdam was about six blocks from the Concertgebouw. After romanticizing the place for my entire life, I was pretty let down to find that it simply translates as "Concert Building.")

The most famous incident of Vermeulen's life, the one every commentator mentions, occurred while he was working as a critic in November of 1918. Following a performance at the Concertgebouw of the Seventh Symphony of the rather conservative Dutch composer Cornelius Dopper, Vermeulen, to express his contempt, yelled "Long live Sousa!" - by which he meant that even the little-respected John Philip Sousa was a better composer than Dopper. Much of the audience understood him, however, to have shouted "Long live Troelstra!", which was the name of a socialist revolutionary who had attempted to start an uprising only days before. For awhile Vermeulen was banned from the Concertgebouw by the orchestra's management. Unable to make a living in Amsterdam, he moved to Paris for a 25-year exile, eking out a living as a music journalist and travel writer. You can see why my heart goes out to the guy. I have a feeling Vermeulen and I would have been thick as thieves.

After World War II, and the war-related deaths of his wife and son, Vermeulen moved back to Amsterdam, and his works started to be heard. There is a "Complete Matthijs Vermeulen Edition" of his recordings on two three-CD sets on Donemus, sold in every record store in Amsterdam but rather difficult to locate on internet retail outlets. His twenty-odd works are easily listed:

Symphonies:

No. 1, "Symphonia carminum" (1912-14)

No. 2, "Prelude à la nouvelle journée" (1919-20)

No. 3, "Thrène et Péan" (1921-22)

No. 4, "Les victoires" (1940-41)

No. 5, "Les lendemains chantants" (1941-5)

No. 6, "Les minutes heureuses" (1956-8)

No. 7, "Dithyrambes pour les temps à venir" (1963-5)Chamber music:

Cello Sonata No. 1 (1918)

String Trio (1923)

Violin Sonata (1924)

Cello Sonata No. 2 (1938)

String Quartet (1960-61)Songs with piano:

On ne passe pas (1917)

The Soldier (1917)

Les filles du roi d'Espagne (1917)

Le veille (1917; also in orchestral version of 1932)

Trois salutations à Notre Dame (1941)

Le balcon (1944)

Preludes des origines (1959)

Trois chants d'amour (1962)Other:

Symphonic Prologue, Passacaglia, Cortège, and Interlude to The Flying Dutchman (1930)

That's it: Vermeulen's life's work. The symphonies - only the Fifth of which is divided into movements - are amazing. All of his music is tremendously contrapuntal, with many lines competing in a vast rhythmic heterophony. Throughout his life he complained that musicians who looked at his scores warned that the music would never sound, but that no one would play it to prove the point - and when he finally heard his works, they sounded just the way he wanted. He flows back and forth across the threshhold of tonality and atonality, occasionally sounding like Ives or Ruggles depending, though really sounding very much like himself. One of his most lovely and characteristic effects is the atonal (or dissonant) background ostinato, over which lengthy melodies unfold. It's complex music, difficult to become familiar with, but not at all without personality. In weight and density one might compare the symphonies to those of Karl Amadeus Hartmann, although they are not nearly so complicated in form as Hartmann's, and easier to take in as a whole.

I was directed to Vermeulen by a casual comment from Anthony Fiumara, director of the Orkest de Volharding. The name was totally unknown to me. I would have never believed that I, lifelong connoisseur of obscure composers, someone who teaches Berwald and Dussek in the classroom, would discover, at 51, a major composer I had never heard of, let alone one who would quickly become one of my favorites. At Donemus I bought the scores to the Second, Third, and Sixth Symphonies. It turns out that my erstwhile Fanfare magazine colleague Paul Rapoport wrote a book titled Six Composers from Northern Europe, about Vermeulen, Vagn Holmboe, Havergal Brian, Allan Pettersson, Fartein Valen, and Kaikhosru Sorabji, which remains one of the fuller treatments of Vermeulen in English; the one existing biography is only in Dutch. And since I hate to tell you about any music you can't hear, I upload Vermeulen's Third Symphony for your listening pleasure. Keep in mind it was completed in 1922. It's amazing what you can reach your fifties without knowing, but delightful to realize how much left there is to learn.

UPDATE: I found an insightful and thorough article on Vermeulen here.

There are, I admit, composer mugs that pop up on the front page of New Music Box that I get sick of seeing week after week, but I was very pleased to see Lois Vierk's friendly face appear to advertise Frank Oteri's interview with her. As Frank correctly reports, Lois seemed on the verge of a career breakthrough in the mid-90s, when she came down with an obscure, nearly impossible-to-diagnose neural condition that has put her out of the public eye for several years. She explains the details to Frank, and reveals, luckily, that she seems to be pulling out of it. She also recounts details of how she structures her pieces, stuff that I wish I had known when I wrote my American music history. Good interview. Lois is a tremendous talent, and I do look forward to her return to musical society.

The interview reminds me of a slight anecdote that took place at one of Lois's Roulette concerts in the '90s. I was sitting next to a composer friend whose love life was a continuing soap opera and an endemic shambles. Lois's pieces all had the same kind of exponentially accelerating form that she describes in the interview. Between two of them, I leaned over and facetiously asked my friend, "Lois seems able to build every piece around the same form. Why can't you and I do that?" "Fear of commitment," was her whispered answer.

(In fact, that further reminds me of how Lois and I met, at New Music America in Minneapolis in 1980. After a concert, like a typical grad student, I was the first to the refreshment table at a post-concert reception. Lois walked up, and we talked. I was single, and somewhat on the prowl. But another guy neither of us knew came up and joined us. Sometime later, she married him.)

I also have to comment on the death of Leonard B. Meyer, author of Emotion and Meaning in Music, Music, the Arts, and Ideas, and other books. The Times has a nice obituary. Meyer's books hit my generation in college, and were the primary aesthetic tomes against which, and in defense of which, we sharpened our rhetorical skills. In the latter book, he laid out a future of endless polystylistic stasis, "the end of the Renaissance," which at the time seemed daring, foreboding, and unlikely. Today we've come to live pretty comfortably in the world he was the first to predict. Meyer was one of the few musical figures of my time that I would have liked to meet and never did.

The commonest and cheapest sounds, as the barking of a dog, produce the same effect on fresh and healthy ears that the rarest music does. It depends on your appetite for sound. Just as a crust is sweeter to a healthy appetite than confectionery to pampered or diseased one. It is better that these cheap sounds be music to us than that we have the rarest ears for music in any other sense. I have lain awake at night many a time to think of the barking of a dog which I had heard long before, bathing my being again in those waves of sound, as a frequenter of the opera might lie awake remembering the music he had heard.

- Thoreau, Journals, December 27, 1857

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog