main: October 2007 Archives

Pianist Geoffrey Douglas Madge and the Orkest de Volharding, conducted by Jussi Jaatinen, play my Sunken City three times this week. The entire program is:

Huib Emmer - Electric Shadows (2007)

John Luther Adams - For Jim (rising) (2007)

Philippe Bodin - Elastique (2007)

Kyle Gann - Sunken City (Concerto for Piano and Winds In Memoriam New Orleans) (2007)

John Coolidge Adams - The Chairman Dances (arranged by Anthony Fiumara)

This is the first concert I know of to include pieces by both John Adams's. Three performances in The Netherlands:

October 30, 20.30

Kassa de Doelen

Schouwburgplein 50, RotterdamOctober 31, 20.15

Felix Meritis

Keizersgracht 324, 1016 EZ, Amsterdam

tel. +31(0)20 626 23 21November 4, 15.30

Concert en Gehoorzaal

Doopsgezinde Kerk, Lange Noordstraat 62

Middelburg

See you there.

I stayed in Aarhus, Denmark, courtesy of Wayne Siegel, a California-born composer who's lived in Denmark since 1974, moving up to the position of the country's only official electronic music professor. Wayne and his wife, the novelist Elisabeth Siegel, have a pet jackdaw named Alice. A jackdaw is a raven-like bird, though smaller, native to Europe. Having been rescued as a baby bird by a man with a beard, Alice loves men with facial hair, and took to me right away. She's noisy, as birds tend to be, and every sound I would make in her presence she would instantly answer with a loud chirp, so instantaneously that we were practically in sync. Wayne has a piece for bass clarinet and tape called Jackdaw, heavily laced with samples of Alice's singing. And here she and I are together (that sliding glass door is open, and sometimes she goes out for a spin, but always comes back):

Everyone with an opinion about the future of classical music should read Richard Taruskin's elegantly brilliant article "The Musical Mystique" in last week's New Republic. Once again, with razor-sharp points and machine-gun energy, he's articulated things I deeply believe that I had never gotten around to formulating in words. His target this time is the Germanic view, prominent among the musical elites of America and Britain, that art and entertainment are different spheres, and we owe it to ourselves to eschew entertainment and cultivate a love of art because, well, because it's art. His impetus is a trio of "Oh-my-god-classical-music-is-dying" books, and his well-supported conclusion is, classical music isn't dying - it's changing. Hallelujah, and pass the popcorn.

In my callow youth I was a proponent of the view Taruskin attacks, a real Adorno-ite, art-is-good-for-you, pop-music-dismisser. I'm stubborn as hell, and yet I got over it: why can't other people? One of my best assets, I think, is a strong sense of musical reality, which I attribute to having been deeply exposed to music before I could talk. And even though I grew up rather shockingly distant from my generation's beloved rock 'n' roll, my sense of reality told me fairly early on that there was nowhere to draw a line between the pleasure I got from listening to, say, Bruckner or Feldman, and the pleasure that I got from the occasional Brian Eno or Residents song that I was driven to listen to over and over again. And I slowly realized that I didn't get that pleasure from listening to, oh, Schoenberg's Piano Concerto, or Carter's Second Quartet, which I did out of a rather pious sense of duty and a feeling that they would build character. And then, of course, the new music, or Downtown music, or experimental music, or whatever delicate euphemism you terminophobes want to apply to the music that I wrote about at the Village Voice for 19 years, was a repertoire dedicated to plastering in the gigantic crack between pop and classical. Some of that music was more conventionally entertaining than other pieces, but there was no way to deeply appreciate that music and pretend that art and entertainment were separate human activities. I can boast a virtuoso range of ways to be entertained, but any music I'm not entertained by I quit listening to, no matter how highly ranked it is in the history books.

And this is the common-sense tack Taruskin takes, with plenty of erudite historical context. Why does any of us get into music except for pleasure? And why would a composer try to do anything in his music except elicit pleasure? Keeping in mind that there are thousands of varieties of musical pleasure, from the algebraic to the sensuous to the perverse to the brain-teasing to the cathartic - and that the pleasure of feeling smugly superior to one's fellow man, which is also in there, is not a very healthy one. The people who praise Art and decry the lazy blandishments of Entertainment, he says, just happen, coincidentally, to be the very people who take upon themselves the prerogative to define what Art is for all humanity. What, Taruskin asks, are these authors' "objective and abstract criteria of musical worth? Merely what any university or conservatory composition teacher will tell you they are." "It is all too obvious by now," he continues,

that teaching people that their love of Schubert makes them better people teaches them nothing but vainglory, and inspires attitudes that are the very opposite of humane....

There are at least as many reasons why they listen to classical music, of which to sit in solemn silence on a dull dark dock is only one. There will always be social reasons as well as purely aesthetic ones, and thank God for that. There will always be people who make money from it--and why not?--as well as those who starve for the love of it. Classical music is not dying; it is changing.

Let it change, let it change, let it change - that is this blog's ubiquitous mantra. But I can't do his rapier-etched argument justice, and I'm reduced to quoting him. You should just go read him.

UPDATE: Thanks to those who offered to translate: I took the first person up on it. As for reading the fine print, you can drag the image to your desktop and it will open as a much larger image (at least this works on my Mac).

ON THE TRAIN FROM BASEL TO HAMBURG - For years I've wanted to visit the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel and look through the Conlon Nancarrow archive there, full of manuscripts that I last saw in his studio in 1994, while he was still alive. I've finally done it. It wasn't quite the cornucopia I had imagined. While all of the official works in his oeuvre have been catalogued, the great bulk of his papers await classification. Hit-and-run interlopers like myself, Nancarrow book or no Nancarrow book, aren't allowed to charge in and start throwing precious manuscripts around. I had to request specific folders like anyone else, and was unable to satisfy my mind on many mysteries of the man's music that continue to puzzle me.

However, I found myself working elbow-to-elbow with two other Nancarrow experts: Dragana Stojanovic-Novicic of the University of the Arts at Belgrade, a surprisingly knowledgeable aficionado of American music who is writing monographs on both Nancarrow and the trombonist-composer Vinko Globokar; and Wolfgang Heisig, a fellow composer from outside Berlin who writes copiously for player piano. We quickly gravitated toward each other and indulged heady conversations relentless in their musicological detail. No need to remind us that Nancarrow published only five articles in Modern Music, nor that it was between Studies Nos. 21 and 22 that he filed off the limiting notches on his roll-punching machine: we all knew all about it. Any divergences of opinion we ran across were so picayune as to require a microscope. And so we, an American, a Serb, and a German in Switzerland, spent every precious available moment in the bowels of the Sacher Stiftung, poring over Conlon's piano rolls - the rolletariat, Wolfgang dubbed us - and spent our evenings at restaurants comparing notes and stories.

Dragana knows my books better than I remember them myself, and was at no loss for conversing about a figure as obscure as Dane Rudhyar, which is more than I would be able to say for all but a very few American musicologists. She's going through Conlon's correspondence, and was able to relate detailed content of letters I wrote to the great man from 1988 on, letters of which I have no memory. I was forced to admit she knows details of my relationship with him better than I do. (I figured at least she didn't have the letters Conlon wrote me, because they're sitting at home in my file cabinet, but it turns out he made copies before sending them - perhaps showing more concern for posterity than he generally evidenced?) Wolfgang gives concerts of the Player Piano Studies on his player piano - not a Disklavier - and he's convinced that the methods of translating the rolls into MIDI information aren't sufficiently accurate. So for years he's been painstakingly copying the piano rolls by hand, tracing them with various tools onto transparent paper. He's even restored some notes included in Conlon's scores, but that Conlon neglected to transfer to the piano rolls, so Wolfgang prides himself that his rolls are even more complete and accurate than Conlon's own. Wolfgang has even made a piano roll of my Disklavier piece Texarkana. I hope to hear it someday on the more authentic instrument.

As for my own research, I managed to type a complete copy into Sibelius of Para Yoko, a 1992 player piano piece that I was never able to photocopy while Conlon was alive, as well as pore over the long-lost manuscript of Study No. 13, and give a few baffled glances at the original player-piano score of his final work, the Quntet for the Parnassus ensemble. If I ever write another article about Nancarrow, it will be an annotated, rhythmically precise score of Study #41, and I was also able in a couple of days to gather all the numerical information I needed from the work's punching score to accomplish that. That's Conlon's best and most important work, in my opinion, from among the ones whose final score (as published in Soundings) gives only an approximate and insufficient idea of the actual rhythms involved. The scores of his late works scatter notes in proportional time notation as though they were thrown down in a fit of inspiration, but analysis of the earlier punching score shows that he always had in mind a rigorously beat-oriented tempo conception. An annotated score of that piece (also needed for Studies 20, 25, 28, 29, 42, 45, 46, 47, and others) would make that clear, and is necessary to nail down exactly what Nancarrow accomplished.

Stiftung director Felix Meyer apprised me of a raft of new Nancarrow recordings that will be appearing shortly, bringing to light hitherto unknown pieces and new versions of old pieces. And he confirmed that the recent "mystery piece" that appeared in the tape used by the Merce Cunningham dance that I recently wrote about was an early study, originally called No. 3, abandoned, and in more recent years resurrected as an homage piece titled For Ligeti. You would have thought that Nancarrow's official 65 works, almost all for one instrument, represented as cut-and-dried an output as the 20th century afforded, but an army of researchers is proving that we've so far only scratched the surface.

The Sacher Stiftung

Tomorrow night (October 18) at 8, pianist Lois Svard is playing my music in a program at Muskingum College in Concord, Ohio. She'll play my recent work On Reading Emerson (which is coming out on a New Albion disc with Sarah Cahill any minute now), along with "The Alcotts" from the Concord Sonata, Bill Duckworth's Imaginary Dances, and George Tsontakis's Ghost Variations. Gann and His World, indeed.

Thursday, October 25 [note - I had originally listed the wrong date], I'm giving a concert of microtonal and Disklavier works at the Mendelssohnsaal of the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Hamburg, Germany. My solo program will include Unquiet Night, Charing Cross, So Many Little Dyings, Bud Ran Back Out, and my own C#-minor Prelude Custer and Sitting Bull. (Anyone still get that joke?) Address in Hamburg: Havestehuder Weg 12, showtime 8 PM.

In other news, microtonal composer Jarod DCamp (a Henry Gwiazda student from the Fargo flatlands) has started a Live-365 internet radio station for microtonal music called 81/80 Microtonal Radio. Among people who never listen to it, microtonal music often has a reputation for dry convolutedness, a devotion more to theory than to sound. It is and isn't true: the proportion of lousy music in microtonalia is about the same as in any other genre, but sometimes the inability of people's ears to adjust to the intonation gets blamed for nonexistent sins. The initial strangeness is what turns me on, and Jarod's station will prove that there are a million varied reasons to step outside the bland 12-pitch scale, since he's showcasing all of them. I'm already astonished by all the bizarre new music I've heard by composers I didn't know. Way to go, Jarod!

As for Postclassic Radio, it got an infusion of British music when I visited England and Wales, and as you'd expect it's about to be flooded with Dutch music. Keep listening, dank u wel. And hey, all you foreign postclassical composers: You want your music played on Postclassic Radio, just invite me to your country and make a big deal out of me!

AMSTERDAM - I'm not over here just turning European musical society on its ear, you know. In fact, I don't seem to be doing that at all. I haven't yet had to place a revolver on the piano to quell potential riots, the way Antheil did when he came to Europe - audiences here have simmered down over the years. But besides performing and lecturing, I'm also working on my book, whose title had already changed from Music After Minimalism to Music After the-Music-Formerly-Known-as-Minimalism, and now may have to be titled The-Music-Formerly-Known-as-Minimalism and its Aftermath. Oh, I know what you'll say, that if I wanted to research American music I could have stayed and done that in America. But that's just what they were expecting me to do. No no, the thing to do, obviously, was to load everything on my hard drive and come study it over here, so I can give it the faux-expat perspective.

The latest title change is due to my realization that I can't simply begin my story in 1978 and build it on the current absurd caricature of what the general public thinks minimalism is, as revealed at Wikipedia and elsewhere. I don't want to spend a lot of time on well-traveled territory like Music for 18 Musicians and In C, but I do have to give enough of minimalism's early history to clarify that it was more of a 20- or 30-composer movement, not just a four-composer movement, as the public thinks (nor a 500-composer movement, as Wikipedia's indiscriminating savants imagine). I can't explain postminimalism to people who will assume that what the postminimalists were reacting to was The Death of Klinghoffer; nor can I fully clarify Peter Garland, Larry Polansky, and Band of Susans to people who don't know the crucial contributions to minimalism made by Harold Budd, Jim Tenney, and Phill Niblock. And so I'm getting resigned to greatly expanding the section on minimalism, which will also make the book more marketable to publishers, since books on minimalism already exist, and publishers are petrified of taking chances on anything that threatens to convey too much new information. By temperament, new information is the only kind I enjoy imparting.

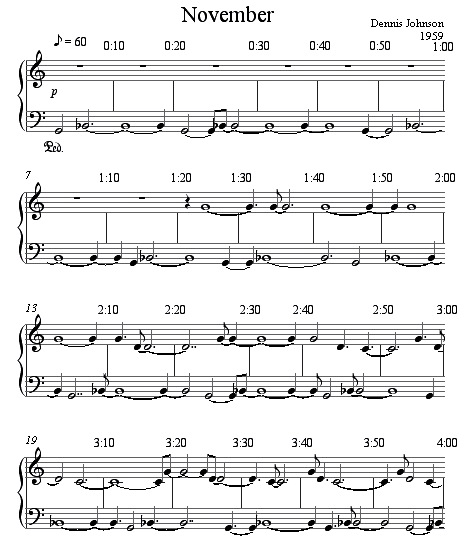

Toward this end, one of the projects I'm enjoying working on is transcribing little-known minimalist keyboard works. Some minimalism was improvisatory, and even some that wasn't is documented only by recording. At the moment I'm working on November by Dennis Johnson, the 1959 piano piece that La Monte Young credits as having inspired The Well-Tuned Piano. Johnson was one of a trio of students at UCLA in the late 1950s who were exploring La Monte's idea of slow, static music, along with La Monte himself and Terry Jennings. Terry Riley joined in soon afterward. Johnson figures heavily in La Monte's semi-famous "Lecture 1960," and is also credited with (among several conceptual pieces, including one that consisted of just the word LISTEN), a work titled The Second Machine that uses only four pitches drawn from La Monte's Trio for Strings. Soon afterward, however, Johnson abandoned music and went into computer science. November seems to have been the magnum opus of a heavily abbreviated career.

At one point La Monte mentions that November was "theoretically" six hours long. The hiss-filled, barely audible surviving recording, however, made on reel-to-reel by Jennings and Johnson (which I've never played on Postclassic Radio because the quality just doesn't make for pleasant listening), cuts off abruptly after 100 minutes. It's slow enough that one could almost take all the pitches down in dictation in real time, but I'm trying to painstakingly document all the exact rhythms in order to facilitate replicating the performance. Below, I give the first four minutes of the piece, but this isn't a good notational solution: what I want to use eventually is just stemless noteheads proportionally spaced, but I'm not sure I can do that in Sibelius. Still, I've played this excerpt (on Sibelius) simultaneously with the original recording, and the notes line up almost exactly:

We can't ask Dennis Johnson about it: he's disappeared. La Monte's last e-mail from him said that he was sick and tired of battling internet problems, giving up on the 20th century, and going out of e-mail contact. He lived in California, and at one point lost his house in one of those humungous wildfires they have out there, and if there ever was a score to November (as La Monte thinks there was, but doesn't remember much about it), it's probably lost. Jennings, of course, died long ago. So it's just me and the recording, on our own.

If anyone knows of Dennis Johnson's whereabouts, please get in touch.

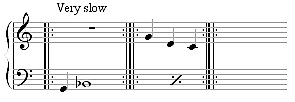

But think about what was going on musically in 1959, look at the example above, and tell me that wasn't a radical thing to come up with. The classical world was pretty much divided up at the time among the crazy-mathematical 12-toners, the chance-obsessed Cageists - both groups resolutely atonal - and the neoclassicists who were still writing huge, brass-climaxing symphonies. Feldman was writing slow, soft music, and as late as 1965 Jennings's slow music was atonal and rather Feldmanish. But November caresses a spare, sad G minor from the piano, protominimalist in both diatonic tonality and repetitiveness. Keep in mind that in the above notation I'm trying to preserve the specific performance, not recreate the score. There is no reason to assume every note was notated: the entire first five and a half minutes of the score might easily have boiled down to this:

And look how many aspects of later music the piece anticipates:

1. Diatonic tonality. The standard minimalist line is that Terry Riley reintroduced diatonic tonality into minimalism with his String Quartet of 1960, but this turns out not to be true. That mythic quartet wasn't in circulation until recently, and I and other scholars were misled by Edward Strickland's Minimalism: Origins book into characterizing it as being in C major, but what Strickland evidently meant was merely that it had no key signature. Musicologist Ann Glazer Niren corrected this notion in her talk at the recent Minimalism conference in Bangor, and played some excerpts of the piece, which is basically atonal, though entirely soft in dynamics. (Keith Potter's book gets the facts right, too, but without examples.) Riley's diatonic music came later, first toyed with in a May, 1961, String Trio, later developed in In C (1964) and the ensuing Keyboard Studies. (There is an important precedent for diatonicism, of course, in Cage's piano pieces of the 1940s like In a Landscape and Dream, and some of Lou Harrison's pieces as well, but it's unclear whether these had any impact on the early minimalists.)

2. Phrase repetition, which Johnson does not seem to have picked up from La Monte, though he did follow La Monte in using slow tempos.

3. Additive process - since each phrase adds more and more notes as it repeats, in a manner that La Monte would later use in an odd little 1961 requiem called Death Chant (with the same pitches: G, Bb, C, D), but more famously adopted as the method of Phil Glass's early minimalist works.

Plus, there are other aspects specifically relevant to The Well-Tuned Piano:

4. First of all, the idea of letting a continuous piano piece run six hours, if indeed November was originally that long.

5. The very gradual introduction of new pitches, which is The Well-Tuned Piano's recurring M.O.; and,

6. the partitioning of a long piece into various contrasting pitch regions. At 9:37 in the recording, November adds in E and F# as the initial transition to a kind of B-minorish area. This is also almost exactly the point in the 1981 Well-Tuned Piano recording at which the music begins to move from the Opening Chord (on Eb) to the Magic Chord (on F#); the coincidence itself is insignificant, because the onset of that transition varies from performance to performance, but it points up how closely Johnson's harmonic conception anticipated La Monte's.

7. Plus, IF the piece wasn't fully notated - and that's an if we probably can't resolve - it would have given La Monte a model for a piano solo only indeterminately notated.

Of course, November is for conventionally tuned piano (Tony Conrad brought just intonation into the mix somewhat later), achieves no powerful acoustic overtone effects, employs no elaborate over-arching thematic scheme (at least, not one observable in the first 100 minutes), and is not the mind-blowing, sumptuously evolved masterpiece that The Well-Tuned Piano eventually became. Nevertheless, it is monumental on its own terms, and certainly marks more historic firsts than we have a right to expect from any one piece. And until we revive what's left of it, which I hope to do in both performance and an article for the next minimalism conference, we miss a key piece of the puzzle of how minimalism sprang into existence.

Another spare-moment project I'm undertaking, incidentally, is a transcription of Harold Budd's 1982 New Music America performance of Children on the Hill, one of the most gorgeous things I've ever been present for. Though well preserved, that's another tape not suitable for public consumption because a remarkably loud and obnoxious baby, seemingly closer to the mike than Budd was, wailed like a demon through 50 percent of it. That kid's about 25 now, and I hope he finally got whatever it was he wanted. Budd recorded Children on the Hill for one of his early, Eno-produced records too, but that's a stripped-down five-minute version; at NMA he extemporized gloriously for 23 minutes. Some of the best minimalism ever made is still languishing away on private tapes.

This Tuesday, October 9, at 8:30 PM I'll be presenting half of a microtonal concert at the Karnatic Lab in Amsterdam, at their De Badcuyp space, 1st Sweelinckstr. 10 in Amsterdam. The Karnatic Lab is a concert series run by Ned McGowan, devoted to music that takes off somehow from the classical music of southern India, and by extension therefore any music exploring microtuning in general. This concert features myself, Ned playing a duet with recorder player Susanna Borsch, and the Scordatura Trio, which consists of vocalist Alfrun Schmid, violist Elisabeth Smalt, and on keyboards my good friend Bob Gilmore. Bob is the Irish musicologist who wrote the excellent Harry Partch biography, edited a recent volume of the writings of Ben Johnston, and has now nearly completed a biography of Claude Vivier - while playing microtonal keyboard with his other hand. They're offering music by Phill Niblock (a 23-minute piece wriggling slightly around an E-minor triad - now that's minimalism!) and Guy De Bièvre.

I'll be playing So Many Little Dyings, my 1994 sampler piece based on Kenneth Patchen's voice, off of my laptop for the first time, along with the premiere of my new version of Custer and Sitting Bull, freshly sound-engineered by composer M.C. Maguire. Also a world premiere of a new piece I whipped up for the occasion called Charing Cross, named for where I was sitting when the idea poured into my head. It's a quirky, cheerful little tune with 39 pitches to the octave, which is the most I've ever used, and the only thing in doubt about the performance (aside from whether I can remember the words to Custer) is whether I can get the 88-key keyboard I need. 61 just doesn't do it for me anymore. I'll post a recording after the concert, but I don't want to spoil the premiere.

Brian McLaren sent me this:

I love how the piano keys run out to the very edge of the piano. And end on E.

I've been posting way too many photos - probably more of you have already seen Yurp than I imagine - but I couldn't resist this image of John Luther Adams (front) listening to his Veils and Vesper installation at the Muziekgebouw:

It was a fantastic space for it, high-ceilinged and well insulated from other spaces despite its openness, and surrounded on various sides by wood, concrete, metal, and glass - tieing in conceptually, in that respect, to John's percussion music, which groups instruments via those categories. Walking among the different loudspeakers, you got a strong sense of each veil giving way to the next, like wandering through a series of waterfalls. I wish I could post a soundfile for you, but the music occupies ten full octaves, and contains lots of subtle acoustical stuff - like Phill Niblock's and Eliane Radigue's music, it would never survive MP3-ization.

In response to my last post, John offers:

Last year I revisited Emerson's expansive essay "Nature". As always, I was amazed at the breadth and depth of Emerson's mind. And I realized how much I'd missed in my earlier readings. Soon after, I rediscovered Thoreau's final essay "Walking". Reading it took my breath away, like listening to the music of the hermit thrush. It felt to me like coming home.

As you say, Emerson and Thoreau couldn't be closer in spirit. Yet their sensibilities couldn't be more different....

In my own music, the human presence isn't represented in the music itself. It's there in the presence of the solitary listener immersed within the music.

After years composing music inspired by landscape, my recent works - particularly the installations - have literally become places. Now, I'm beginning to invite the human presence of performing musicians to traverse those lonely landscapes. Still, creating place in sound, time and space remains the heart of my work. I feel this is the best gift I can offer to my fellow human animals.

As our species begins to stare our own possible self-induced extinction squarely in the face, I believe that music can serve as a sounding model for human consciousness. Music can help us remember how to listen, and how to know our place within the larger world we inhabit.

All very true. As for me... well, at least I drive a Prius.

AMSTERDAM - The painter Philip Guston was Morton Feldman's best friend. In 1970, Guston abandoned the abstract expressionist style he had been closely associated with, and began painting cartoonish figures that often included shoes, disembodied eyeballs, and hooded figures. To say Feldman was shocked would be an understatement. As someone recently told me the story (heard from someone else who was there), Feldman came to the initial exhibition and Guston came up to ask him what he thought. For several minutes, Feldman simply couldn't speak, and Guston slowly and sadly got the point. Finally Feldman just turned away and left, and the two parted ways for years. And Feldman wasn't the only one. "It was as though I had left the church," Guston later recalled; "I was excommunicated for awhile." The dependably venomous Hilton Kramer titled his review of the show, "A Mandarin Pretending to be a Stumblebum."

Guston: The Street

I have a couple of upcoming performances in Amsterdam, and I got here early to see John Luther Adams and to hear his beautiful sound installations Vespers and Veils. John and I have fantastic conversations. Something about the interaction of his profundity and vagueness and my superficiality and sharpness gives off sparks that seem to intermittently illuminate all of existence. Perhaps the most mind-blowing musical conversation I've had in my life was one John and I had about a year and a half ago, walking through the snow and cold outside Fairbanks. I keep meaning to blog about it someday, but I'm still trying to process it. I'll tell you about it when I can do it justice.

John, as everyone knows, is a composer whose paradigm is nature. Vespers and Veils, based on prime-numbered harmonics of the overtone series, are softly roaring continua. All of John's works, by his own frequent admission, have to do with the incredible Alaskan landscape he lives within. His pieces are walls of sound: not impenetrable, but gorgeous, relentless, ebbing and flowing, swelling and dispersing, piling up in waves that stretch beyond one's concert-hall attention span. Veils engulfs you and makes you just want to sit down and be quiet. His orchestra piece For Lou Harrison, just released this month on New World, is a series of avalanches, each one quite like the last but different in detail, before whose massive beauty one can only submit. His music is big, beyond human in its scope, and as impersonal as it is translucent.

Back in the '80s, I tried to be the kind of composer John is. It was in the air. Cage had unleashed the force of nature into music, and everyone was obsessed with sonority and process, trying to get their own personality out of the music and let nature speak for itself. The objectivity of 12-tone music had given way to a perhaps even greater objectivity of process-oriented logic. But over years of experimentation, I found that nature didn't speak through me. The natural processes I came up with were more tedious than compelling. I loved Cage's music, and La Monte Young's, and Steve Reich's, and John's, but it was not mine to write. Whatever joy I took in composing had to do with the personal and subjective: the quirky melodic decoration, the unexpected key change, the rhythmic figure that seems bizarre at first, but finally becomes familiar through repetition. I greatly admired the composers of nature, and wrote about them enthusiastically, but I was not one of them. My muse led in a different direction.

I'd been thinking about this difference between me and John lately, and in discussing it, we wandered into Feldman and Guston. Both of us largely base our music in a Feldmanesque paradigm, an ongoing continuum of only subtle dynamic change. For me, Feldman was not a composer of nature, though he is ambiguous in this respect, and the question is one about which reasonable people could disagree. "Those 88 notes are my Walden," he said, referring to the piano keyboard, and I interpret that to mean he saw himself not as a channel for nature, but as the Thoreau-like individual reacting to nature. I hear the anxious melodic figures in Rothko Chapel as psychological, not natural, conscious of their alienation and attempting to find release or resolution or integration. Take the incredible passage near the end of Feldman's For Philip Guston where the music strips down to just four chromatic pitches for a full 25 minutes, and then suddenly opens up into a pure C-major scale across the entire piano: that's no natural process, the result of no inevitable logic, but an incredible psychic release after almost unendurable repression. Of course, I'm cherry-picking my examples to make the point.

What was revealing was the differing reactions John and I had to Guston's heretical pictorial style. When he first encountered it years ago, John, he said, had the same reaction as Feldman: he couldn't believe that a great abstract expressionist had turned away from the wonders of pure color and shape to paint naive-looking figures with strangely personal, idiosyncratic associations. It took him awhile to decide that Guston's late works were no less masterful than the early ones. I first knew Guston from his earlier work as well, but the shoes and giant eyeballs and hooded figures flooded me with an instantaneous sense of relief. It was liberating. I had been a Jackson Pollock fanatic, or thought I was, but Guston made me realize that I was hungry for art to reintegrate the human element, the personal element, the whimsical and idiosyncratic. Nature is a paradigm that an artist can hardly help worshipping, but ultimately I felt that we also need an art that is about being human, with all the attendant neuroses, embarrassments, longings, and humor. I love(d) abstract expressionism, but I wanted to know how, once we had made our way through it, we were going to come back to dealing with the uncomfortableness and absurdity of human consciousness.

It helped that Guston's paintings were cartoon-like. I love cartoons myself, and in the '90s found myself drawn to what I think of as my cartoon music, the stylized appropriations of musical clichés. I especially let myself go in my Disklavier pieces: the rhythmically dislocated ragtime of Texarkana, the deadpan tango rhythm of Tango da Chiesa. I flatter myself that, like Haydn, Ives, and Satie, I am one of the rare composers capable of purely musical humor, independent of extramusical references. My entirely representational Custer and Sitting Bull, with its trumpet calls, Indian flutes and drums, and "Garry Owen" quotations, taps into obvious prototypes. There are deliberate caricatures in my music, skewed pictures and appropriations of familiar musical phenomena.

I fear that, to the sophisticated new-music fans who've learned to love the sublime blankness of John's self-evident canvases, those caricatures must seem like a naive back-pedaling. I often use secondary dominants, and even in these days of returned diatonic tonality, such familiar chords are not "signifiers" of originality. Composers (though never John) sometimes react to my music with the same disappointment that Feldman showed Guston's late work, denigrating it as merely pastiche or satire, and I've learned very well how it feels to seem like a mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum. On the other hand, I think my music may be more comfortable for fans of 19th-century classical music than John's, in whose wide canvases they might miss a certain expected level of surface detail. In 1989 John Rockwell, kinder than Kramer, called my music "naively pictorial," and it was a phrase from heaven. I've carried the banner of "naive pictorialism" ever since.

I wrote a piano concerto about hurricane Katrina - only it skips over the hurricane. The first movement, "Before," is an expression of happy thoughtlessness; the second movement, "After," is about anger, mourning, betrayal, recovery, and includes a stylized image of a New Orleans funeral. If John had written a Katrina piece, it would be about the hurricane. It would be a hurricane.

The "natural" path was not easy to abandon. "New music," as we called it back then, was almost definable as music that "let nature take its course." Back in the day I even gave a New Music America lecture titled "The De-Spiritualization of Sound," about how new music was now about sound waves and not personality, but I gave it with an uneasy conscience. Distinctions like natural versus psychological, literal versus metaphorical, are not trivial: they are the axes in reference to which we position ourselves to stake out aesthetic territory and explore what music means and what it can accomplish, because, thankfully, we'll never know everything music can achieve. But just as it was fundamentally stupid to think, as so many did in the '50s, "OK, the age of tonal music is over, from now on music can only be atonal and anyone who lapses back into tonality is not with the times," it would be equally stupid to think that "history now demands" that music now be always literal in its depiction, or that psychological metaphor must be abandoned as old-fashioned. George Rochberg was right: the problem with 12-tone music was not what it added to our vocabulary but what it tried to subtract, that it attempted to outlaw anything associated with the past. The history of creative music never goes backward, but neither does it ever decide that one side of a creative duality is now useless, and only the opposite side can be gainfully explored.

What's most fascinating for me, though, is that, if you made an aesthetic map of the new-music world, John would be nearly my closest neighbor. It is immodest of me to link myself with him, I know, because he is far better known as a composer than I am. But as he and I discuss it, we both share a backyard boundary with Peter Garland, with Jim Fox and Mikel Rouse next door, Michael Gordon down the road one way, Larry Polansky the other way, and like that. You couldn't find two composers more in the same "camp" than me and John. We have the same influences, similar histories, the same heros, the same dreams. But our brains are wired differently, and all those new-music impulses that hit his brain and turn into vast celebrations of nature hit mine and turn into quirky celebrations of personality. He once called me a "force of nature," but that was a generous projection: he's the force of nature, I'm a force of culture. (Quite parallel, John still models himself after Thoreau, while I long ago realized I actually prefer Emerson.) It's astonishing how diametrically opposite people with so much affinity for each other can be when you look at them close enough.

Rumor had it that Pierre Boulez performed in Amsterdam at the same time as the Output Festival, and I think I ran across his group:

Isn't this the Ensemble InterContemporain, with Pierre on the far right playing drum? In any case, they were the hottest music I've heard here so far. There was a lot of I, flat VII, flat VI, V over and over in the bass, but for variety they'd go into I, V, I, ii, V, and there were so many repetitions that I can't imagine how they kept everything straight at the riotous tempo they took. I was most impressed with the clarinetist in the blue jacket: he'd keep a lit cigarette between his fingers while playing, and puff on it between solos. Fast, fast, fast music, loud and relentless, yet melodically elegant. I had never before thought about writing something for two clarinets, two accordions, sax, and drum, but I'm sure as hell thinking about it now.

...is fantastic, isn't it? I don't think there's been any part of this trip I've looked forward to more than just hiding away in some cubbyhole where no one knows how to reach me, and composing my pointy little head off. The phone doesn't ring, no one stops by, people start to assume you're unreachable, there's no refrigerator full of tempting food, there's not even anything on the walls worth looking at, and if you're in a country where you don't speak the language, even the idea of trying to run out and do errands is pretty disinviting. It's like sensory deprivation, only comfortable. Even back home, I've often threatened to go check into a hotel so I can get some work done. And I'm not in a hotel but a short-term apartment, which is even better. There's no front desk, no maid trying to come in. I have a little kitchen, and a considerable economic incentive to avoid expensive restaurants and eat at home. My only connection to the outside world is this internet cable, and if you need a favor from me, uh, oh yeah, sorry, the blasted internet doesn't work well here, I didn't get your message. You'll never find my phone number here, never. And if I may bring up Kierkegaard again, the Dane had a motto I have always admired: Bene vixit qui bene latuit - "He has lived well who has remained well hidden."

Sites To See

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary