main: February 2007 Archives

Bernadette Speach has passed along to me the extremely sad news of the death, Saturday, from lung cancer, of violinist-composer Leroy Jenkins. He was just shy of his 75th birthday, but he never seemed old. Wiry, lively, young for his years, he was a comforting presence in the new-music world, with his raspily idiosyncratic but perfectly controlled violin tone that seemed as much at home floating up from the orchestra pit of his operas as in improvisations with Oliver Lake. Talking to him, you forgot after awhile that jazz and classical music had ever had their differences, he flowed between them with such fluid ease. He worked a lot with Muhal Richard Abrams and other AACM greats, but once told me a story about getting sick from all the decadent rich food during an extended weekend at Hans Werner Henze's house. The music theater works of his that I was privileged to review, The Mother of Three Sons and The Negro Burial Ground, would be well worth reviving.

Bernadette Speach has passed along to me the extremely sad news of the death, Saturday, from lung cancer, of violinist-composer Leroy Jenkins. He was just shy of his 75th birthday, but he never seemed old. Wiry, lively, young for his years, he was a comforting presence in the new-music world, with his raspily idiosyncratic but perfectly controlled violin tone that seemed as much at home floating up from the orchestra pit of his operas as in improvisations with Oliver Lake. Talking to him, you forgot after awhile that jazz and classical music had ever had their differences, he flowed between them with such fluid ease. He worked a lot with Muhal Richard Abrams and other AACM greats, but once told me a story about getting sick from all the decadent rich food during an extended weekend at Hans Werner Henze's house. The music theater works of his that I was privileged to review, The Mother of Three Sons and The Negro Burial Ground, would be well worth reviving.

I'm late mentioning this, but pianist Blair McMillan is performing some of my Private Dances this afternoon at Da Capo's concert at Bard College.

On March 3, Ensemble Green is performing my chamber piece New World Coming at the Renaissance Arts Academy (1880 Colorado Blvd., Los Angeles) at 8 PM. Also on the program are works by Marc Lowenstein, Peter Knell, and Lou Harrison's Grand Duo for Violin and Percussion.

Even more exciting, James Bagwell will conduct the Dessoff Choir in the premiere of my My father moved through dooms of love at Merkin Hall in New York on March 10. Works by William Duckworth, James Bassi, Philip Rhodes, and Elliott Carter also on the program. This one I'll be at.

One of the unexpected kicks of being at the Atlantic Center for the Arts is being here with artists from other disciplines and observing professional differences of behavior. My composers and I are here with poets, who are working with Marie Ponsot, and architects, working with Steve Badanes. The poets are mostly middle-aged women, and, as they themselves were the first to point out, all arrived wearing scarves, even the men - not thick, cold-weather scarves, but tasteful, decorative, muted-color, poetic scarves. The male architects are big, beefy guys who shave their heads, and the women are tall and thin. They think it's funny that we composers are all joined at the hip to identical Mac laptops, and I'm sure it does look comical. On the first day we got a tour of the studios. The music studio has a sound system, computers, several MIDI controllers, a piano, mixers, and so on, and the visual art sudio has machines for cutting wood and metal and lots of heavy equipment. Then we went to the poetry studio, which contained: a paper cutter. The poets didn't even bring computers, and walk around with nothing but pencils and paper. The composers spend the first 20 minutes of any event trying to get all their technology to work. We're all artists, with the same aspirations and complaints, but it's humorous how different - and how predictably so - our day-to-day lifestyles are.

Now that I'm out of my spider hole for a few weeks, I'm learning that the internet is killing my small-talk skills. If I launch into a story, "I ran into Bob Ashley the other day...," the answer is a quick, "Oh yeah, we read that on your blog." Last time I tell you guys anything interesting.

I'm basking in the February sunlight of Florida's east coast as I write this, enjoying a free morning at the Atlantic Center for the Arts. Joining me here as Associate Composers (a term that makes me uncomfortable as conjuring up the "associates" at Wal-Mart, though then I start wondering what it means to be an associate professor) are Michael Maguire, Carolyn Mallonée, Teresa Hron, Andrea La Rose, Maria Panayotova-Martin, Scott Unrein, Matt McBane, and Jim Altieri. It's a convivial and musically excellent group, and listening to each other's music, we're already kind of astonished at how good everyone is. (These are also the people whose music I recently uploaded to PostClassic Radio, so you can hear there what we're hearing. I'm sneaky that way - clues as to my goings-on appear on the station frequently.) Michael, whom I'd been writing about for 18 years but never met until yesterday, and I are the old-timers, already rehashing the aesthetic battles of our youth, as the thirty-somethings view us with besumed pity. (Over Laphroaig last night, Schoenberg made Michael's top-five list of 20th-century composers, and didn't make my top fifty.) Anyway, we're here for three weeks of discussion and arguing and composing, and I couldn't feel more in my element. And it's so blessedly far from snow. You'll be hearing more, certainly.

The Dessof Choir is performing my piece My father moved through dooms of love at Merkin Hall in New York on March 10. (Also on the program are works by James Bassi, Elliott Carter, my good friend William Duckworth, and Phillip Rhodes.) Preparatory to that, choir member (and fellow Oberlin grad) Jeff Lunden did an interview with me about the piece, which is up here. I've also made the score available as a PDF on my score page (click on "Choral"). The choir, under my good friend and Bard colleague James Bagwell, did a beautiful job at rehearsal last week, and I'm very excited about this premiere - in some respects the largest I've had in New York.

On most issues on which I am not intransigently stubborn, I tend to be astonishingly suggestible. Someone told me this week that the essence of good web site design was that people should not have to scroll down - that, instead, information should be heirarchically arranged on nested pages, because people would rather click than scroll. OK. So I completely revamped my web site. I think all the pages survived the redesign except that I excised a lot of information explaining who I am, because when I started the site in 1996, I was actively looking for work. Now I'm actively running from it. So now you don't have to scroll, despite the fact that I'm doing all this on a brand-new MacBook Pro, which has a feature whereby you can scroll simply by running two fingers down the finger pad, making scrolling really fun. Anyway, sorry about all the scrolling I've made you do over the years.

Canadian composer and guitarist Tim Brady told me about the European music entrepreneur who came up after one of his concerts and said, "I love listening to your music, it makes me feel so happy." Later the entrepreneur organized a music festival, and explained to Tim why he didn't include him: "After all, this is a serious music festival."

Jazziz gives its critics' top ten jazz album lists in the current January/February issue, and look who made Sam Prestianni's list, down there between Mingus and Jason Moran:

Ornette Coleman: Sound Grammar (Phrase Text/Sound Grammar?)

Gato Libre: Strange Village (Muzak)

Ralph Towner: Time Line (ECM)

Kayhan Kalhor / Erdal Erzincan: The Wind (ECM)

Max Nagl: Quartier du Faisan (hatOLOGY)

Liberty Ellman: Ophiuchus Butterfly (Pi)

Dominic Duval String Quartet: Mountain Air (CIMP)

Charles Mingus: At UCLA 1965 (Mingus Music)

Kyle Gann: Nude Rolling Down an Escalator (New World)

Jason Moran: Artist in Residence (Blue Note)

That's it, fellas, I'm outa the ghetto. Good luck with your new music, or avant-garde music, or postclassical music, or whatever the heck you call it, come hear me at Birdland and let me know how you're doing with that academic crap.

From Hits to Niches

When I was asked to come up for this conference on "New Music and the Media," I tried for weeks to think what new music and the media could possibly have to do with each other aside from both being eight letter phrases in which the second word begins with M. But then I talked to Tim Brady, who made me realize that my thinking had been very pre-9/11, as they say, and that I had been limiting the media to what we now universally refer to as the MSM, or the "mainstream media," which of course doesn't cover new music to any appreciable extent.

As a new-music critic for the Village Voice newspaper for 19 years, I used to be a representative of what we might now laughingly refer to as the AMSM, or possibly altMSM - the "alternative mainstream media." Laughingly, because now that the Village Voice has been bought by the huge corporation New Times Media, it has become one of 17 so-called "alternative papers" across the U.S. run by a large conglomerate that saves money by running the same film reviews in all those papers. Which means that the difference between the altMSM and the MSM now runs about as deep as the difference between unscented Ivory soap and regular scent Ivory soap.

Declining to join the new, more corporate altMSM, I graduated instead to the Blogosphere, where the media - by which I suppose I would include music blogs and classical music web sites - does cover new music, and quite extensively. As a member of the altMSM, I used to be an expert. I knew what went on in the Village Voice offices, and you didn't. I knew what the paper's editorial policies were, and you didn't. As a citizen of the Blogosphere, on the other hand, I am not an expert, or rather, I am as much of an expert as most of you are, and no more. The blogs I read you can also read. The information I have access to on the internet, you also have access to. I can't even tell you how to set up your own blog, because my blog was set up for me by ArtsJournal.com, so if you've started your own blog, you know more about blogging than I do.

Journalist Gary Kamiya at Salon.com wrote an article last week about the experience of having hundreds of people posting comments, many of them critical and even vituperative, after every article he wrote. One of the comments posted in reply suggested that, from now on, writers need to adopt a more humble and conversational tone, because we no longer speak ex cathedra to a faceless audience that can't speak back. So it seems to be a symptom of our recent intellectual climate change that I give this keynote address not because I am an expert on new music and the current configuration of media, but simply because I was the one of us who was asked to speak for the crowd. I will attempt to keep my remarks humble and conversational. I am going to try to put some ideas in order, but I rather despair of telling you anything most of you don't already know. The cultural paradigm to which we have recently switched is too new to be tremendously complicated yet, and one gets the sense that everyone has followed along so far. Culturally, and at least for the moment, the internet seems to have brought us all on the same page. In fact, the fact that you can't all immediately post comments disagreeing with me after I finish speaking today fills me with a certain sense of nostalgia.

So one of the effects of our climate change is to call into question the notion of expertise. Bob Christgau, dean of rock critics, who was recently fired from the Village Voice by the conglomerate that bought it for the crime of having too high a salary, wrote recently that newspaper criticism is dying because people have too many other places to go for recommendations, and no longer need to read the experts. For every compact disc you consider buying, you can look on the relevant page at Amazon.com and read reviews by people who have presumably have heard, or possibly haven't heard, the disc - for instance, if you look at my last CD there are two reviews that so misdescribe the music that they obviously didn't bother listening - and then those reviews are reviewed by the people who read them. The old saying "Everybody's a critic" is now literally true. Even publicly, judgment is no longer a specialized function.

But I have learned recently that in losing my privileged status as an expert, I have not merely receded into the great undifferentiated stream of humanity. Oh no. For awhile I was a "content provider," which I rather liked because it made me sound so - contented. As it turns out, though, I am not merely a content provider, that is, one who exudes words and images to fill a space between advertisements. As a content provider known for particularly precise recommendations, I am also a filter in the navigation layer. (I just found this out a few days ago. I feel like the prince in the film The Madness of King George who learns that he is also Bishop of Osnabrück, and comments, "It's amazing what one is, really.") You can't simply alphabetize all of the recordings that have ever been made and let people sift through them looking for something that might appeal to them. People who are looking for someone who sounds like Norah Jones would end up accidentally having to listen to my music, and become terribly perplexed. So the sea of digital music has a navigation layer: a network of links from one piece to another and one type of music to another, so that, given one recording you like, you will soon be reeled into the niches in which you feel at home.

The components of that navigation layer are filters, both mechanical and human. You've all seen the mechanical filters at work. If you recently bought a DVD of Sir Laurence Olivier's Henvy V on Amazon, the next time Amazon might suggest that you will also enjoy the films Regarding Henry, Henry and June, and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. Most people already tend to prefer human filters, I think, which are more intelligently contextual and efficient. To be a good filter does not require, as being a good newspaper critic did, being a good writer, nor does it require intelligence or even taste (one could be a filter, after all, of Gilligan's Island episodes). What it does require is voluminous access to a certain niche literature and some degree of organization. In these areas I am exemplary. My access to postminimalist music of the 1980s and '90s is unparalleled. That is my niche, and almost no one cometh to that niche except through me.

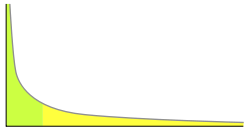

It's one of the smallest niches on the internet, but that doesn't matter anymore. For to be a filter is to be a guide into what is now called the Long Tail. The term originated in a 2004 article, later turned into a best-selling book, by Wired magazine editor Chris Anderson. (I apologize to all of you who already know all about the Long Tail, but I will be as humble and conversational in describing it as I can.)  The idea is that if you rank any phenomenon according to frequency, such as book or record or beer sales, you get a distribution graph with a vertical part that curves into a horizontal part. For instance - and I take this example from Wikipedia -

The idea is that if you rank any phenomenon according to frequency, such as book or record or beer sales, you get a distribution graph with a vertical part that curves into a horizontal part. For instance - and I take this example from Wikipedia -

in standard English, the word the is the most common word... about 12% of all words in a given text are the, while [the word] barracks occurs in less than 1 out of 60,000 words, but cumulatively, words roughly as rare as barracks make up about a third of all text.

So occurences of the word the would register way up at the top part of the graph, while occurrences of barracks would be way down in the long tail. But while instances of the vastly outnumber instances of barracks, rare words down in the Long Tail make up almost as much of our written language as common words like the.

The application to music, I think, is pretty obvious. The other day when I was writing this, the number one top-selling artist on Amazon was Norah Jones. My latest CD came in at number 234,754. However, in terms of sales there are thousands of times as many Kyle Ganns, as many artists who sell only a few hundred CDs, as there are Norah Joneses who sell hundreds of thousands of CDs, to the extent that the thousand least-known composers represented on Amazon may altogether sell as many or more CDs as Norah Jones does by herself. Therefore, if you have a brick-and-mortar store with only room to offer a hundred CDs, you will of course want to sell Norah Jones rather than Kyle Gann, but you will miss out on the equal sales you could be making from the thousands of artists whose CDs only sell a few copies each. This is where the internet comes in, because, not having storage issues, it can offer both Norah Jones and Kyle Gann and his myriad ilk. You walk the streets of Winnipeg trying out record stores, and you'll have a complete Norah Jones collection several times over before you find a Kyle Gann CD. But you go to Amazon and type in "Norah Jones" and "Kyle Gann," and either name comes up just as fast as the other.

Chris Anderson talks about how the era of "hits," of blockbusters, is over, giving way to the era of niches. Pardon me if you've already read this on the internet, but I'll quote at some length what he says in elaboration:

Most of the top fifty best-selling albums of all time were recorded in the seventies and eighties... and none of them were made in the past five years... Every year network TV loses more of its audience to hundreds of niche cable channels... The ratings of top TV shows have been falling for decades, and the number one show today wouldn't have made the top ten in 1970.

In short, although we still obsess over hits, they are not quite the economic force they once were. Where are those fickle consumers going instead? No single place. They are scattered to the winds as markets fragment into countless niches. The great thing about broadcast is that it can bring one show to millions of people with unmatched efficiency. But it can't do the opposite - bring a million shows to one person each. Yet that is exactly what the Internet does so well.

He describes talking to a Mr. Vann-Adibé who engineered an internet jukebox, and says,

During the course of our conversation, Vann-Adibé asked me to guess what percentage of the 10,000 albums available on the jukeboxes sold at least one track per quarter...

The normal answer would be 20 percent because of the 80/20 rule, which experience tells us applies practically everywhere. That is: 20 percent of products account for 80 percent of sales (and usually 100 percent of the profits).

...Half of the top 10,000 books in a typical bookstore don't sell once a quarter. Half of the top 10,000 CDs at Wal-Mart don't sell once a quarter...

So Anderson guessed 50 percent. The correct answer was 98 percent. That is, 98 percent of the tracks on the jukebox sold at least once per quarter. Doing research, he found that this 98 percent was pretty much a rule: whenever an internet company made a vast quantity of selections equally available on the internet, 98 percent of the products showed evidence of some demand every quarter. And he goes on:

...As the company added more titles to its collections, far beyond the inventory of most record stores and into the world of niches and subcultures, they continued to sell. And the more the company added, the more they sold.

Each company was impressed by the demand they were seeing in categories that had been previously dismissed as beneath the economic fringe... For the first time, I was looking at the true shape of demand in our culture, unfiltered by the economics of scarcity.

This description accords perfectly with my experience. I go around lecturing on new music and playing it for audiences, and everywhere I go, I find and create demand for new music. People come up to me afterward and ask, "That music was fantastic, where can I find it?" I run an internet radio station for new music, and people write to tell me all the time about the wonderful composers they discovered listening to PostClassic Radio. And then, on the other hand, I talk to publishers about books I want to write, and exactly as Anderson says, they invariably dismiss the music I'm a filter for as "beneath the economic fringe." They say, "Oh, we can't publish a book about that music, there's no interest in it." And newspaper editors tell me, "Oh, we wouldn't run a story about that music, there's no interest in it." For 25 years I've been shuttling back and forth between two realities, one in which there's patently plenty of demand for new music, and another in which there is confidently asserted to be no demand whatever.

The concept of the Long Tail now gives me a way to make sense of my experience. The book publishers, the newspapers, the radio stations, the record stores, are caretakers of the vertical part of the graph. They all make a living by finding out what items will be bought or appreciated by the largest number of people and offering only that. And for 25 years I've been a Chicken Little alarming people because that vertical stack of hits has gotten thinner and thinner and thinner, and more and more difficult to get one's music into.

When I was young, the best new music was on big, well-known labels like Columbia and Deutsche Grammophon. By 1980, those labels had abandoned new music, which was now on prestigious specialty labels like Lovely Music and New Albion. By 1990, the music I was most interested in writing about for the Voice was now on even smaller labels, rarely available in stores, like Mode and Artifact and Cuneiform. And by 2003, the music I most wanted to put on my radio station was at best on tiny labels run by the composer, like Mikel Rouse's Exit Music or Bang on a Can's Canteloupe, and more not even commercially recorded at all, just sent to me, or uploaded to the internet, by the composer. More and more and more of the Long Tail was abandoned by the industry that used to bring new music to the public and keep it alive.

And so it was at every level. The New York Times cut back its arts coverage by 25 percent, and the Village Voice made fun of them. The next month, the Village Voice cut back its arts coverage by 25 percent, and later both papers cut back still further. More and more, newspapers cover only the organizations that give them advertising revenue. The classical musical organizations who most reliably advertise in newspapers are the local orchestras. And so composers whose music gets played by orchestras have always had the most chance of getting publicity; by the 1990s, it seemed like they were the only composers getting publicity. If your music isn't played by orchestras, your chances of getting into the prestigious vertical shaft of the distribution graph covered by the MSM is just about nil.

For 20 years I've been kind of a professional pain-in-the-neck at music conferences, expounding a gloom-and-doom scenario based on the shrinking vertical part of the graph. What my congenital pessimism kept me from noticing was that, as the vertical part was thinning, a lot of institutional sand was running down into the Long Tail. As I read about new music on the internet, I see very different names than I'm accustomed to reading about in newspapers and music magazines. Composers with strong cult followings like Charlemagne Palestine, Brian Ferneyhough, and Phill Niblock get discussed far more often on the internet than they ever did in print. A lot of what we think of as successful establishment composers are nearly absent from the internet. Look up Milton Babbitt or Jacob Druckman, and you may not find much more than music publishers' blurbs, which are notoriously one-dimensional. But look up La Monte Young, or Kaikhosru Sorabji, or Claude Vivier, or the San Francisco composer Erling Wold, and you can find tons of information: scores, analyses, discussion groups, great Wikipedia articles.

Hundreds of scholars squeezed out of the vertical shaft by commercial pressures have emigrated to the internet. One of the first big composer web sites I saw in the '90s was a scholarly site for the Russian composer Cesar Cui; I'm sure its author was ready to write a book about him and was discouraged by publishers, and so blossomed onto the internet. In its discussion of subjects conventionally covered by print encyclopedias, Wikipedia leaves a lot to be desired. But its superiority to any print medium in the coverage of new musical genres and artists not found in dictionaries but nevertheless loved by thousands of people is absolutely phenomenal.

And given my experience hawking new music around the country and in Europe, I get a strong impression that the musical interest I see on the internet is closer to, as Anderson says, "the true shape of demand in our culture, unfiltered by the economics of scarcity." It starts to look to me like the classical music culture whose deterioration we're so panicked about, with its star system, its exclusive character, its timidity in the face of public opinion, its assumptions of economic scarcity, its conviction that you have to choose between me and Norah Jones and there's no room for both, was a neurotic, unreal system whose true purpose was never to disseminate culture, but to make money for the people in power. And what we see on the internet, flawed as it may be (and I'll get to some of its flaws in a moment), is more the result of true enthusiasm expressed by people who have nothing to gain and no reason to say anything but the truth.

Everyone who's sat on grant and award panels knows that often the piece of music that wins is not the one any panelist feels most strongly about, but the one that is the least offensive, that no one particularly objects to. Likewise, I think that for similar reasons of scarcity and the kind of concensus needed, our old musical life created a culture in which the music that aroused the greatest passions often got pushed out into the long tail. As Anderson says, "For too long we've been suffering the tyranny of lowest-common denominator fare, subjected to brain-dead summer blockbusters and manufactured pop." It seems to me that this is just as true in classical new music as it is anywhere else. Newspapers, book publishers, music publishers, orchestras, radio stations, all the various MSM outlets, and even television have a lot to learn from what goes on on the internet: which artists inspire heated discussion groups, which ones merit lengthy articles on Wikipedia, which ones amateur scholars furiously debate each other about. The internet, especially now while hardly anyone makes any money contributing to it, more immediately reflects which music inspires true devotion.

And though the artists best represented there may still seem commercially unfeasible now, the internet's ability to access the rare music of the Long Tail is bound to bring more and more listeners in that direction. Anderson's graphs show that not only does the vertical "hits" part of the distribution curve get thinner, its peaks fall lower, while the Long Tail becomes thicker as more customers discover it. How far the internet can change the landscape might be indicated by the fact that my blog was recently ranked as the number five most influential classical music blog - and we're talking about a blog whose idea of a big-name classical composer is Rhys Chatham. As Anderson writes about the ongoing collapse of the record business:

[T]echnology... offered massive, unprecedented choice in terms of what [people] could hear. The average file-trading network has more music than any music store. Given that choice, music fans took it. Today, not only have listeners stopped buying as many CDs, they're also losing their taste for the blockbuster hits that used to make them throng those stores on release day. Given the option to pick a boy band or find something new, more and more people are opting for exploration, and are typically more satisfied with what they find. [p. 33]

As they wander farther from the beaten path, they discover their taste is not as mainstream as they thought (or as they had been led to believe by marketing, a hit-centric culture, and simply a lack of alternatives). [p.16]

[A]s... companies offered more and more... they found that demand actually followed supply. The act of vastly increasing choice seemed to unlock demand for that choice. [p.24]

"More and more people are opting for exploration." I don't remember the 20th century very well, but I do seem to recall that that what 20th-century composers used to dream about most was that, someday, more and more people would opt for exploration. All my life I've lived in the Long Tail, without exactly recognizing that's where I was. And it turns out they decided to build the information superhighway right through the middle of it. (I can imagine how excited Canadian composers are by this news, since they evidently see their entire music scene as inhabiting the Long Tail.)

And so, very recently, the internet has been turning me from a pessimist into an optimist. Of course, our global climate change is submerging tropical islands, while turning some frigid wastelands into new tropical paradises. Likewise, our intellectual climate change will doubtless destroy as well as create. Some things are bound to be lost, and we don't know yet what will replace them. One thing that's been lost, most notably, is the ancient practice of getting paid. Most of the work I do on the internet I do without compensation, and no one's quite figured out what to do about that yet.

Secondly, I have trouble seeing what's going to replace editing. Back in my old ex cathedra days, I used to spend 90 minutes a week going over my Village Voice column with a brilliant editor, Doug Simmons, who had studied classical rhetoric in college. Of course, I was being edited for the arrogant, magisterial idiom, but some of that training still carries over into the humble, conversational style I am careful to use today. As I look through internet discourse, much of the writing I read, even when it reveals taste and intelligence, falls into clichés, common syllogisms, academic obfuscation, and a general lack of specificity and clarity. My own apprenticeship in this area was arduous if exhilarating, and took seven years, and I don't see where the pressure to improve the level of the discourse is going to come from.

There's an analogy I often take from the field of piano tuning. Piano tuners tell me that if you know how to tune pianos traditionally, then the new electronic tuning machines make it easier; but that if you can't do it traditionally, and start out relying on the electronic tuner, your pianos will never stay in tune for very long. I sometimes apply this to composition: that if you know how to compose on paper with a pencil, you can make the transition to composing directly in music software, but that if you don't, you'll always have issues with continuity and timbre. Some poets say something similar about writing poetry on a word processor. And it may apply to many other transitions to digital technology.

One change I haven't figured out yet is who my new audience is. Going from the altMSM to the blogosphere created an illusion that I was addressing a vastly larger crowd. My statistics page tells me that 55 percent of my readership is in the East Coast time zone, 10 percent on the West Coast, 12 or 15 percent in Western Europe, and now and then 1 or 2 percent in the time zones that include India or Australia. My blog can be read from anywhere in the world, which gives me a heady feeling of addressing the planet.

At the same time, I notice that I get comments mostly from the same 75 or 100 people who leave comments at New Music Box and Sequenza 21, and that they all seem to be composers. When I wrote for the Voice, anyone who wanted to read the political news or the pop record reviews, or look through the sex ads, at least had my column under their arm, and was likely to flip past it, perhaps notice it. Now it seems that I am read by a small, if widely dispersed, crowd of internet-obsessed composers who all frequent the same web sites and comment on each other's blogs. A lot of the work I have always done has been advocacy for composers, and it makes no sense to advocate composers to other composers. It seems to primarily piss off the composers you're not doing advocacy for. Advocacy for composers only works when directed to the music-loving public, or to power-brokers who arrange performances and recordings, and we composers are all reading each other. Ironically, our ability to reach out to the entire world may have led, for now, to a kind of hermetic professional parochialism.

How these issues will work themselves out, we don't know yet. It's difficult to give a keynote address in the dead center of a large cultural transition, especially one that has done away with the concept of expertise. But all that's speaking as a writer, as a former expert, as a filter on the navigation layer. Speaking as a composer, I used to despair that the older I got, the more the traditional needs of the composer - publication, performance, recording, distribution, publicity - seemed to be becoming more and more elusive. But now that the internet has ushered the world into the Long Tail, it's not so lonely down here anymore, and I've come to feel optimistic. I now trust that some 98 percent of you will share my optimism - at least once a quarter.

Gratifyingly overheard in the dining room of the Fairmont Hotel in Winnipeg, where I've come to give the keynote address for the Winnipeg Symphony's Canadian New Music Network conference:

"Kyle Gann's a good choice. He's in touch with the younger generation, and doesn't just talk about the same old famous composers."

UPDATE: I should maybe point out that the object of advertising this wasn't just to make you think I'm cool, but to suggest that a lot of people are tired of talking about "the same old famous composers."

I've just finished the second keynote address I've ever written, and I think it's the most difficult genre of writing I've run across. It's easy to show up for a panel and present your personal point of view, needle some people, be a provocateur. It's easy to do some research and write a purely objective encyclopedia article or lightly-spun program note. But a keynote address can be neither personal nor merely factual. It has to anticipate and express the collective concerns without taking sides, frame any possible argument among your audience members, and you're not always quite sure who your audience is. The issues must be sharply drawn, yet without divisiveness. A world must be circumscribed and a stage set, with no particular outcome implied or favored. It is the prologue to a play that hasn't been written. Magnanimity and incisiveness must flow in graceful alternation. And I've come to have a larger measure of respect for the people who do it on a regular basis.

I was fearful that the Atlantic Center for the Arts, where I am headed in a couple of weeks, and of which so many artists hold fond memories, might have been in the path of the tornado that ripped through Florida last week. I kept imagining the composer's cottage blown into the Atlantic. But I have been reassured that it missed them by a few blocks. I land in Daytona Beach airport during the Daytona 500 and leave during Canadian colleges' spring break, and it sounds like I will meet chaos enough.

Saturday morning at 10 I'll be giving the keynote address for the biennial conference of the Canadian New Music Network, in conjunction with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. I can't quite discern from their website where it's taking place, but I guess anybody in Winnipeg can tell you. So if you're near Winnipeg this weekend on your way to... on your way... well, I'll tell you about it afterward.

Sarah Cahill's goading me about my piano skills (in the comments) brings to mind an incident from my youth that I've been remembering lately. I foolishly quit taking piano lessons late in my undergrad career. Three years go by, and, finishing my doctorate at Northwestern, I thought I should study piano again while I still had the chance. I was assigned to Lawrence Davis, a sharp, meticulous, expert chamber musician who spent his life grooming his hotshot undergrads to become concert pianists. (He's no longer listed on the faculty; seems like he was in his 50s 27 years ago, and may well still be around.) He was not happy about having to mentor this great, hulking composition student with rusty finger technique, but to his eternal credit, he realized I was more knowledgeable than his budding Horowitzes, and he gave me music to work on that would challenge me intellectually, even if it was too difficult for me.

The most ambitious thing Davis had me play was Beethoven's Op. 90 sonata, to this day nearly my favorite Beethoven. The piece opens with the same chord played twice:

One day, five times in a row he yelled "Stop!" during that little eighth-note rest between the first and second chords and made me start over. He just did not like the way I played that first chord. We spent quite a bit of time on the first two measures without me really grasping what was wrong. At last he let me go ahead and run through the entire movement. After the final chord, no immediate comment seemed forthcoming. I looked over and saw that he was turned away from me, quietly weeping.

Actually, this spurs me to make a complaint about grad schools that I've nurtured for a long time. In grad school I took piano lessons with a professor who did not want to be teaching a non-major; I took conducting classes with a conductor who did not want a non-conducting-major in his class; and I took philosophy seminars with professors who resented having a music major sit in. By and large, these were some of the best things I did in grad school. The theory courses I was supposed to be in were mostly a linear continuation of what I'd studied at Oberlin, and I could have learned that material on my own. With the exception of Peter Gena's fantastic late-Beethoven course, it was the courses outside my major that did the most for me - and it was a shame that I had to draw that benefit under the nagging discomfort of the professor's visible and continuing disapproval. Because of that experience, I have always tried to be especially supportive of non-majors whenever I've taught graduate courses - and undergrad ones.

My biggest regret about my life is that I didn't continue practicing piano. In 1982 I started typing instead, and that was that. Now I'm writing a piano concerto, and it would be energizing to imagine myself playing it with an orchestra someday - but that's not going to happen. When I was 19, playing Chopin polonaises and Brahms rhapsodies along with my Wolpe and Rochberg, it would have seemed a possibility.

My other big regret is how seldom my intensely busy life allows me to see my close friends, who are scattered out from Alaska to Germany. A related regret is the difficulty of even keeping in sufficient touch by e-mail. The longest, most meaningful, most searching e-mails are the hardest ones to find time and mental space to answer. The succinct e-mails that require no reflection have a split-second turnaround time:

"Did you ever find a punching score for Nancarrow Study 13?"

"No."

"Thanks."

The e-mails that deserve a long, thoughtful response, not only from close friends but from strangers with strong mutual interests, pop up as I've just finished editing a recording and have to dash to the post office before it closes, and I make a mental note as I'm off to a concert, and I don't get back to them that night while fifty more e-mails come in, and they start drifting down my e-mail box, and someday I have an hour to spare and I go searching for the e-mails I most wanted to answer. I imagine it's the same for us all - the messages most deserving of a response hang in the ethernet as unanswered questions. The feeling of muted, unfulfilled, but tangible connectedness that remains, which the internet does much to reinforce (even if it also heightens our awareness of the facile negativity that flows around the world), will have to be sufficient consolation.

I hadn't replenished PostClassic Radio in well over a month, and to my horror Sarah Cahill told me that a friend of hers, a devoted listener (so that's who's logging on), had now heard the entire current playlist. Well, it's no longer true - 19 new recordings just went up by a crowd of composers mostly quite a bit younger than myself: Andrea La Rose, Matt McBane, Paula Matthusen, Andrian Pertout, Teresa Hron, David Toub, Jim Altieri, the amazing M.C. Maguire, Carolyn Mallonée, Kevin Volans, Scott Unrein, Jo Kondo, plus a Flute Trio by Feldman newly out on New World with flutist Dorothy Stone. Nice stuff. More to come, don't stop listening now.

UPDATE: Someone actually complained that I don't have any of my own music programmed lately (all right, it wasn't a complaint exactly, he was just wondering, and come to think of it, he did sound a little grateful), so I've fixed that. I try not to repeat pieces, and I just don't compose fast enough, or rather record fast enough, to keep contributing.

I treasure your comments, which at this point, I believe, take up well over half of my total blog space. There's no way I'd turn off my comments feature: the dialogue is too good, I've gotten tons of helpful feedback, and being able to put up your comments directly saves me a lot of time. From my own experience reading comments on other blogs, though, it detracts from the enjoyment when someone posts a comment that goes on for paragraph after paragraph, all out of proportion to the other comments and sometimes longer than the blog entry itself. You don't want to miss anything because someone might respond to it, but you begin to suspect that someone's nerve has been struck and he's going to go on for pages about his pet peeve. Also, this not being a group site, it's not an effective place to grandstand, shout down the other commenters, and try to get in the last word. On your blog you get the last word, and I get the last word on mine. For more general and democratic discussions, go to Sequenza 21 or New Music Box. I've deleted a few comments lately for various combinations of verbosity and bellicosity, and I always feel guilty doing it, but I'm the bouncer here, and I do it to preserve the enjoyment of others.

Another bounceworthy infringement, as I've noted before, is writing in to disparage music I write about. Say, Carl Stone or somebody is sitting off in Japan minding his own damn business, and I put up a fragment of an mp3 of his music, and five people write in to say how much it sucks, and Carl's being spat upon, when he didn't have any control over the presentation, and maybe I didn't explain his music correctly, and maybe I played an old version or the worst two minutes, and it's not fair to judge composers on fragmentary work of theirs I present for analytical or musicological purposes. Sometimes I'm merely trying to illustrate a point. I'm writing about postminimalism now, and there's a lot of great postminimalist music and a lot of bad postminimalist music and a lot in-between. So if I play or describe something that's in-between because it illustrates my thesis, that's not a cue for everyone who doesn't like that fragment to roar in exulting that, Aha!, just as they suspected, postminimalism sucks. We've got to be able to discuss music without instantly confronting the earth-shaking question of whether you LIIIIIIIIKE the music or not, as though being LIIIIIIIKED was music's sole purpose for existing. There are people who are very quick to reject new ideas without thinking about them much, or studying the scores of the music that inspired them, and usually those people seem to be in gradyooate school. Well, I was in gradyooate school once myself, and I knew everything. Someone should have given me a high-powered job just at that moment, because I had the entire world figured out, and I knew for sure which was the good music and which was the bad and why. And now I'm 51 and confused and can't figure out how the world works or where it's going, nor where to draw the line among the 171 shades of gray I see everywhere, and guess what? Now they let me teach. Go figure. But at least I don't sit here going onto blogs of musicians more experienced than myself and tell them their ideas are bullshit, and neither should you.

I've been too busy recording a new CD to take note, but in response to my postminimalism essay composer Galen Brown has started his own history of postminimalism over on Sequenza 21. It's in installments, and he got to talking about conceptual art, and I don't know where he's going with it yet, so it's kind of a cliff-hanger. I look forward to Episode 2.

For years I've wished some younger Kyle Gann would come along and take over the responsibility I still feel of chronicling music of my generation. I strongly suspect that the Village Voice, under new and less idealistic management, would no longer hire a person to do this, but it might be worth a try. Of course, Tom Johnson's devout fans were terribly disappointed in Greg Sandow, and Greg's fans were just as disappointed with me, and so if someone does come along and make a career out of describing and contextualizing the new music, he or she'll likely make no friends among people who like what I do. But I'll root for him anyway.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog