main: May 2006 Archives

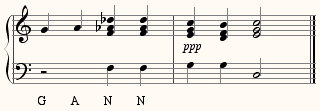

Every year I end up talking at some point about soggetto cavato, the practice of making themes from the letters of people's names, the way Schumann used "S - C - H - A," better known as "E-flat - C - B - A," to stand for himself in Carnaval (S being German for E-flat, and H for B natural). I commented on the limited possibilities of my own name in this regard, but my student Ezekiel Virant came up with a possibility I hadn't considered: a G and A followed by two Neapolitan chords, the Roman numeral analysis symbol for the Neapolitan being an N:

By this logic, I guess the first letter of Virant's last name could be expressed by a V chord, or the submediant could cover the first two letters by itself.

While we're talking about student takes on my name, for years I've been teaching the movements of the mass:

Kyrie

Gloria

Credo

Sanctus

Agnus dei

according to a mnemonic that a student named Jason came up with back when I was at Bucknell:

Kyle

Gann

Can't

Sing

Anything

It's also helpful in that I can use the movements of the mass to help me remember what it is that I can't do.

I caught the last night of John Luther Adams’ sound installations, Veils and Vesper, at Diapason Gallery in New York Saturday night. Now, right off, how can you not like pieces with titles like that? Immediately Veils conjures up some Debussy impressionism, and is there a piece with “Vesper” in the title that anyone can not like? You think of Monteverdi’s Vespers for the Blessed Virgin, and a little screwdriver pokes in and disconnects part of your critical apparatus before you walk in the door.

As befits those titles, Veils and Vesper were lighter, less mammoth, easier to take in than John’s installation The Place Where You Go to Listen that I wrote about earlier this spring. Where that vast work continues to chart eternity via weather and seismological data, these two were on six-hour repeating cycles of slowly rising and falling tones. The sound source was all pink noise, filtered once again through Jim Altieri’s Max patches, but diffracted through what John calls “harmonic prisms.” And in fact, you were immediately aware of a kind of tonality, some chord or scale shimmering indistinctly through the slowly shifting web of pitch lines. Putting your ear against one of the loudspeakers, it was difficult to distinguish one tone from another, as though you were hearing C and B at once or in alternation, and within a minute’s listening you could get a feel that the range was gradually rising or falling, but without leaving the basic tonality. Irregularly pulsing low tones from the woofers seemed to enforce a drone on the D of a Dorian scale, so that, reduced to a single impression, Veils seemed to be an endlessly suspended ii7 chord awaiting a resolution that would never come. Meanwhile, within that was an almost imperceptible trickle of sound waves upward or downward, like - if it is not degraded by the comparison - one of those huge, quiet waterfalls over slabs of rock at a fancy restaurant or hotel. Calming, beautiful, and, with those titles to set you up, an invitation to a crepuscular frame of mind.

The effect of music is difficult to describe at best, and in this case seemingly impossible. It’s why, when you know something about how the music was made, it’s so much easier to fall back on technical descriptions.

Pardon me for using this space as a technical support forum in reverse, but I'm not suppose to bother our college Mac guy with problems concerning our personal computers, and Apple charges me an arm and a leg for advice. My G4 laptop, OS 10.3.9, has developed a condition wherein sometimes basic applications like iTunes and Quicktime won't run. They'll seem to start up, but the console will never appear, and eventually I'll have to force-quit. The same thing happens to computer shut-down, it will pretend to begin and then simply won't go through. I've tried re-downloading the applications, with no effect. Is there a simple fix? Any ideas? And thanks if you can offer help.

My umptillion-pitches-to-the-octave microtonalist cohort Brian McLaren sends me a link to a wonderful article on the deficiencies of "Computer Music" by composer Bob Ostertag. Ostertag does a concise job of explaining the snobbishness of those who divide off the "real" electronic composers from the composers "who merely use electronics":

...it is a phenomenon seen time and time again in academia: the more an area of knowledge becomes diffused in the public, the louder become the claims of those within the tower to exclusive expertise in the field, and the narrower become the criteria become for determining who the "experts" actually are....

The cul-de-sac these trends have led "Computer Music" into is a considerably less enjoyable place to tarry due to a technological barrier that is becoming increasingly obvious: despite the vastly increased power of the technology involved, the timbral sophistication of the most cutting edge technology is not significantly greater that of the most mundane and commonplace systems. In fact, after listening to the 287 pieces submitted to Ars Electronica, I would venture to say that the pieces created with today's cutting edge technology (spectral resynthesis, sophisticated phase vocoding schemes, and so on) have an even greater uniformity of sound among them than the pieces done on MIDI modules available in any music store serving the popular music market.

Ostertag, who burst onto the scene with All the Rage - a Kronos Quartet piece integrating recordings of a 1991 gay riot in San Francisco - is a good enough composer to trust on such opinions.

Also, based on comments I'm compiling a list of schools whose electronic music programs (or at least certain faculty) make no elitist distinction between scratch-built and commercial software, and that will allow and teach the latter. So far, apparently, they are

Mills College (I shoulda known)

CalArts

University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Missouri Kansas City

University of Cincinnati

University of San Diego (not to be confused with the University of California at San Diego)

University of Wollongong (Warren Burt chimes in)

Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane

I'm adding to the list as I get further recommendations (see comments - apparently the Australians are a little more open-minded than academic Americans), which will be helpful for all the requests I get about grad schools, and even undergrad schools. Mills College is where we've always had the most success sending our freedom-loving Bard students, and I always hear great things about the faculty there, who have a long tradition of musical liberalism.

It shows my naivété, after 20 years of teaching, that I still hold any illusions about academia. Until recently I had nurtured a belief that electronic music was one area of music in which the otherwise pervasive distinctions between academic and non-academic did not apply. After all, electronic music is the only department in which (you will excuse the term) Downtown composers have been able to find positions in universities. As far as I know, there are currently only two Downtown composers in the country who have ridden into permanent teaching positions on skills other than electronic technology; one of those, William Duckworth, did so on his music education degrees, and the other, myself, masqueraded as a musicologist. All the others work in electronic music, where, I fondly presumed, open-mindedness prevailed.

It’s not true. I’ve been becoming aware that, even among the Downtowners, there is a standard academic position regarding electronic music, and am learning how to articulate it. I’ve long known that, though much of my music emanates from computers and loudspeakers, I am not considered an electronic composer by the “real electronic composers.” Why not? I use MIDI and commercial synthesizers and samplers, which are disallowed, and relegate my music to an ontological no-man’s genre. But more and more students have been telling me lately that their music is disallowed by their professors, and some fantastic composers outside academia have been explaining why academia will have nothing to do with them.

The official position seems to be that the composer must generate, or at least record, all his or her own sounds, and those sounds must be manipulated using only the most basic software or processes. Max/MSP is a “good” software because it provides nothing built in - the composer must build every instrument, every effects unit up from scratch. Build-your-own analogue circuitry is acceptable for the same reason. Sequencers are suspect, synthesizers with preset sounds even more so, and MIDI is for wusses. Commercial softwares - for instance, Logic, Reason, Ableton Live - are beyond the pale; they offer too many possibilities without the student understanding how they are achieved. Anything that smacks of electronica is to be avoided, and merely having a steady beat can raise eyebrows. Using software or pedals as an adjunct to your singing or instrument-playing is, if not officially discouraged, not taught, either. I’m an electronic amateur, and so I won’t swear I’m getting the description exactly right. Maybe you can help me. But at the heart of the academic conception of electronics seems to be a devout belief that the electronic composer proves his macho by MANIPULATION, by what he DOES to the sound. If you use some commercial program that does something to the sound at the touch of a button, and you didn’t DO IT YOURSELF, then, well, you’re not really “serious,” are you? In fact, you’re USELESS because you haven’t grasped the historical necessity of the 12-tone language. Uh, I’m sorry, I meant, uh, Max/MSP.

Where does this leave a composer like Henry Gwiazda, whom I have often called the Conlon Nancarrow of my generation? He makes electronic music from samples taken verbatim from sound effects libraries, and you know what he does to them? Nothing. Not a reverb, not a pitch shift, not a crossfade. He just places them next to each other in wild, poetic juxtapositions, and it’s so lovely. From what music department could he graduate doing that today? Is he rather, instead of Nancarrow, the Erik Satie of electronic music? the guy so egoless (or simply self-confident) that he doesn’t have to prove to you what a technonerd stud he is with all the manipulations he knows how to apply?

Now, there is one aesthetic fact so obviously incontrovertible that it hardly merits mentioning: a piece of music is not good because a certain type of software was employed in making it, nor is it bad because a different type of software was applied. Compelling music can be achieved with virtually any kind of software, and so can bad. You’d have to be a drooling moron to believe otherwise. Given that patent truth, it would seem to follow that there is no type of software a young composer should be prevented from using. The question then follows, are there pedagogical reasons to avoid some types of software and concentrate on others? I am assured that there are: 1. Since softwares come and go, it’s important that students learn the most basic principles, so that they can build their own programs if necessary, rather than rely on commercial electronics companies. And, 2. Commercial software doesn’t need to be taught, all the student needs to do is read the instruction manual and use it on his own.

Let’s take the second rationale first. As someone who just struggled six months with Kontakt software just to get to first base, I don’t buy it. There are a million things Kontakt will do that, at my current rate, it will take me until 2060 to figure out. Even after wading through the damn manual, I’d give anything for a lesson in it. But even given that some softwares, like Garage Band, are admittedly idiot-proof, there are a million programs out there, and a young composer would benefit (hell, I’d benefit) from an overview of what various packages can do. How about a course in teaching instrumentalists or vocalists how to interact with software? A thousand working musicians do it as their vocation, but academia seems uninterested in helping anyone reach that state. It’s unwise to base one’s life’s work on a single, ephemeral software brand, Max as well as anything else - but knowing how to use a few makes it easier to get into others, and some of my more interesting students have subverted cheap commercial software, making it do things for which it was never intended.

Rationale number one is more deeply theoretical. I’m all for teaching musicians first principles. You don’t want to send someone out in the world with a bunch of gadgets whose workings they don’t understand, dependent for their art on commercial manufacturers. Good, teach ‘em the basics, absolutely. You teach ‘em circuit design, I’ll teach ‘em secondary dominants. But why should either of us mandate that they use those things in their creative expression? Creativity, like sexual desire, has a yen for the irrational, and not every artist has the right kind of imagination to get creative in the labyrinth of logical baby steps that Max/MSP affords. I’ve seen young musicians terribly frustrated by the gap between the dinky little tricks they can do with a year’s worth of Max training and the music they envision. I heard so much about Max/MSP I bought it myself, and now have a feel for how depressingly long it would take me to learn to get fluent in it. I thought it must be some incredibly powerful program, from what I kept hearing about it - it turns out, the technonerds love it because it’s incredibly impotent in most people’s hands, until you’ve learned to stack dozens of pages of complicated designs.

There are at least two types of creativity that apply to electronic music, probably more, but at least two. One is the creativity of imagining the music you want to hear and employing the electronics to realize it. Another is learning to use the software or circuitry and seeing what interesting things you can finagle it into doing. There are certainly some composers who have excelled at the second - David Tudor leaps to mind. Perhaps there are a handful who have mastered the first in terms of Max/MSP, but it’s a long shot. Of course, if you’ve got the type of creative imagination that flows seamlessly into Max/MSP, by all means use it. “Good music can be achieved with any kind of software.” But why does academia turn everything into an either-or situation, whereby if A is smiled upon, B must be banished?

There’s an analogue in tuning. I’m a good, old-fashioned just intonationist with a lightning talent for fractions and logarithms. I can bury myself in numbers and get really creative. In nine years of teaching alternate tunings, I can count on one hand the students who have shown a similar talent. Faced with pages of fractions, most would-be microtonalists freeze up and can’t get their juices flowing. Were I a real academic, I would respond, “Tough shit, maggot - this is the REAL way to do microtonality, and if you can’t handle it, then you’re on your own.” But I’m not like that, and I let students work in any microtonal way they can feel comfortable, whether it’s the random tuning of found objects or just pitch bends on a guitar - as long as they understand the theory underlying it. Likewise, some young composers get caught up making drums beat and lights blink in different patterns in Max/MSP, lose sight of their goal, and never make the electronic music they’d had in mind.

In fact, many years of listening to music made with Max/MSP, by both professionals and students, have not impressed me with the software’s results. I’ve heard a ton of undecipherable algorithms, heard a lot of scratchy noise, and I’ve heard instrumentalists play while the MSP part diffracts their sounds into a myriad bits whose relevance I have to take on trust. In the hands of students, the pieces tend to come out rather dismally the same - and not only students. The only really beautiful Max/MSP piece I can name for you is John Luther Adams’s The Place Where You Go to Listen, and you wanna know how he did it? He worked out just the effects he wanted on some other software, and then hired a young Max-programming genius, Jim Altieri, to replicate it. He envisioned the sound, the effect, the affect, but he knew he didn’t possess the genius to create the instrument he needed. Meanwhile I hear lots of beautiful music by Ben Neill, Emily Bezar, Mikel Rouse and others using commercial software that does a lot of the work for them. If we can talk about software as an instrument (and we should), there’s a talent for making the instrument, and there’s a talent for playing the instrument. To assume that one shouldn’t be allowed to exist without the other is to claim Itzhak Perlman isn't really a violinist because he didn’t carve his own violin. It’s ludicrous.

In short, it appears that academia has applied the same instinct to electronic music as to everything else: find the most difficult and unrewarding technique, declare it the only valid one, take failure as evidence of integrity, and parade your boring integrity at conferences. Whatever happened to the concept of artist as a magician with a suspicious bag of tricks? Art is about appearances, not reality, so who cares if you cheat? Our society is truly upside down. Our politicians and CEOs, whom one could wish to keep honest, dazzle us with virtuoso sleight-of-hand, while our musicians, who are supposed to entertain us, meticulously account for every waveform. It’s completely bass-ackwards.

Do I overgeneralize? I hope so. Please tell me that there's an electronic music program that doesn't make this pernicious distinction, and I will send droves of students applying to that school. I was living in a fool’s paradise, and I’m only reacting to what I’m hearing - from disenfranchised young composers, from electronic faculty who proudly affirm the truth of what I’m saying as though it's a good thing, from fine composers who are wizzes at commercial software. One brilliant electronic student composer this year insisted that I advise his senior project: me, who can barely configure my own MIDI setup. I had nothing to teach him; our “lessons” consisted of me grilling him with questions about how to get the electronic effects I was trying to achieve. But I gave him permission to use synthesizers, and found sounds, and let him play the piano in synch with a prerecorded CD. I didn’t emasculate his imagination by forcing him back into a thicket of first principles from which he would never emerge. His music was lovely, crazy, expressive. Another student, a couple of years ago, enlisted me for a children's musical he made entirely on Fruity Loops. It was a riot.

And so I say to all composers who got excited in high school about the possibility of musical software but feel intimidated by their professors’ insistence on doing everything from scratch: go ahead, use Logic, and Reason, and Ableton Live, and Sibelius, and Fruity Loops, and synthesizers, and stand-alone sequencers, and hell yes, even Garage Band, with my blessing. Be the Erik Saties and Frank Zappas and Charles Iveses of electronic music, not the Mario Davidovskys and Leon Kirchners. Resist the power structure that would tie anvils to your composing legs, with a pretense that they’re only temporary. The dogmatic, defensive ideology that‘s in danger of being callsed Max/MSPism is merely an importation of 12-tone-style thinking into the realm of technology. Who needs it?

[N.B.: In the comments, some confusion is caused by the fact that there are two Paul Muller's, with different e-mail addresses. At least they agree with each other.]

I had reported having trouble getting Kontakt 2 sampling software to work on my computer. In April the company released the 2.1 upgrade, which was supposed to make the program run smoother by making the samples much less CPU-intensive. But every time I tried to start up, my screen froze - on a G5 yet! This morning I set out to attack the problem. I spent hours going back and forth with Kontakt tech support. I reinstalled the program from scratch three times. Finally I narrowed it down to the audio setup. I reinstalled my MIDI interface driver twice. I talked to a nice man at Mark of the Unicorn. After seven hours of frustration, it turns out that I have a defective USB port. I unplugged the MIDI cable from the port, stuck it in the next hole, and everything suddenly worked fine.

Kontakt 2.1 plays like a charm. With Li'l Miss Scale Oven to retune it, I now have the retuned Steinway grand I've waited my whole life for. Of course, my hair's noticeably grayer than it was yesterday, and I'm a little snappish.

Blogmeister Douglas McLennan asks the question, Why do professional writers who have regular print gigs bother to write a blog, sans pay? It's a good question, and one I've been asked, but not one I've answered publicly, though it's fairly easy, with multiple answers.

First of all, let's examine the premise that I'm a successful writer in a print medium. Last year, in an attempt to make the Village Voice more profitable for sale, free-lancer rates were slashed; my per-column pay was cut by 52%, which is the largest cut I heard of at the Voice. Since the paper was sold, the music editor has been fired, as has the editor who hired me, Doug Simmons, 20 years ago. Were I to send in a column now, I'm not sure who I'd send it to; I suppose Bob Christgau is still there, but I'm afraid if I check I'll learn he isn't. (I got a letter from Chuck Eddy urging me to sign the new contract, and before I could respond, he was gone, let go because under him the music section had been "too academic." Has there ever been anyone in the Voice music section more "academic" than myself?) These layoffs come, not because the Voice was having financial problems - on the contrary, its recent profit margin, 29%, has been the highest in its history. But the company merged with New Times Media, known as the "Clear Channel of Alternative Weeklies", and its new board members are simply soaking it for as much income as possible, integrity and artistic quality be damned.

For me, a Village Voice without Doug Simmons is not the Village Voice. I'll say nothing against the paper - it saved my life, gave me a career, allowed me to print a million apparently outrageous opinions, and was a great job for 11 years, out of the 19 I was there. I've published my anthology of Voice articles, almost all taken from the 1989-to-1996 years that were my glory period there. Now, one has to admit that except for the building, the Village Voice I used to work for no longer exists. Given that I was already immensely dissatisfied with my paltry 600-word limit, which prevented me from doing any writing I was proud of, I guess it's official: I don't write there anymore.

This is typical of what's happening throughout the print industry. Nevertheless, I still have other writing gigs. My favorite is my bi-monthly "American Composer" column for Chamber Music magazine, which I dearly love because I don't need a news peg to hang it on, and can write about any (American) composer I want, as long as they've written some chamber music. I still write program notes for the Cincinnati Symphony, though there it's extremely rare, as you can imagine, that I get to write about any composer on whom I'm a certified authority. Still, I enjoy sorting out the intricacies of Mahler's Das Knaben Wunderhorn lieder and extolling Carl Nielsen's symphonies, and am happy to do that for money. More importantly, I've got three book projects at various stages, and those are what the blog really cuts into, justifying Alex Ross's definition of blogging: public procrastination.

Even so, I have to admit that, even if I were never paid, I would write up a storm if given an outlet. My reason is the same as Henry Cowell's (who wrote about 225 articles over the course of his career, about a tenth of my total so far). I am a composer, and not only is my music little-known: the very genre I write in, speaking as broadly as possible, is virtually unknown to the public, and is, to the extent that it is known, widely misinterpreted. I could, as a composer, simply write about my own music, which I would be thrilled to do, but few would pay attention. I know what Cowell knew: that there is no such thing as a famous composer in an unknown genre. No one composer can benefit from publicity unless his entire scene becomes a public phenomenon. Listeners need comparisons, context, parallels. And to tell the truth, I, like Cowell, have a strong sense of social responsibility and an inconvenient altruistic streak. I write about the musics of John Luther Adams and Eve Beglarian because I love their work and think you should be familiar with it. Public neglect of them grates painfully on my sense of fairness.

More urgency is given to my writing by the number of people I represent. If you do not hail from the same Downtown scene I have spent my adult life in, you doubtless conclude that my opinions are highly individualistic, curious and occasionally entertaining, perhaps, but marginal because so completely idiosyncratic. It isn't true. When I get together with composer friends - Adams, Beglarian, Mikel Rouse, Mary Jane Leach, William Duckworth, Art Jarvinen, might not mind being mentioned in this regard - we all share pretty much the opinions and concerns that I express. I just happen to be the only one in the group that writes about them. I represent no maverick view, no lunatic fringe, but the very mainstream of composers who, influenced by Cage, Feldman, and minimalism, turned away from the modernist path. Were I to stop writing, a major wing of contemporary music would fall off the map of public discourse almost entirely, as far as any regular coverage is concerned. No one is waiting for "the new Kyle Gann" to appear more eagerly than myself, and he or she is welcome to the bulk of the burden.

And so, from a mixture of self-serving and conscientious motives, I blog, gratis. And there are other reasons:

1. To keep in practice, in case a paying gig comes along. I do fantasize about leaving academia and becoming a full-time writer again, though some tremendous social transformation would have to take place for this to become possible again.

2. To remind people that I'm a pretty darn good writer, in case anyone wants to hire me - although I sabotage this aim when I don't polish my prose very assiduously because I'm not being paid for it, and believe me I notice the difference.

3. It keeps the free CDs coming.

4. Because I truly think that I have some weird brain connection whereby, when I hear music, words pile up in my head, and writing them down is a way of getting rid of them.

5. Someone's gotta keep Alex Ross in line. If not me, who? If not now, when?

Of course, none of this, except for perhaps the free CDs, explains, to me, why anyone else in the print world would write a blog. I'm a pretty clear-cut case; all those other guys are a mystery.

Mark Swed offers a highly appreciative review of the recent REDCAT concert of Ben Johnston's music in the LA Times: "Why is a major composer and authentically original American voice so seldom heard?" Amen to that.

Eric [sic] Satie’s chief defect is that he did not know his place.... Lack of musicianship and discriminating invention, incapacity for clear and continuous thinking, set Satie fumbling for some sort of originality until he hit upon the idea of letting his poverty-stricken creations face the world under high-sounding names. - Eric Blom

Astonishingly, one of our student singers - it was Elizabeth Przybylski, the same young woman who premiered a song of my own - sang Erik Satie’s magnificent Socrate as her senior project. Even more astonishingly, as a double major in French she also wrote a 90-page paper examining Socrate’s place in 20th-century aesthetics. Drawing on a wide range of writings in the psychology and history of art, including T.W. Adorno (who was urged on her by Bard’s French literature professor, I was proud to learn), Liz placed Satie in a tradition of artists who develop a style that is misunderstood and reviled by the public at first, but eventually persuades enough artists of its power and validity that it brings about a paradigm shift - to use the phrase coined and popularized in the history of science by Thomas Kuhn.

Liz’s paper exposed two contradictions that didn’t strike her as sharply as they did me. One was that, after describing for pages how Satie drew on popular musics like ragtime and dance-hall songs for his compositional idiom, she mentioned that he went on to write in an “unpopular” style. You have to be pretty steeped in classical-music culture for this not to sound oxymoronic. Yet I spend much of my life writing about composers whose reliance on, and attempts to integrate, popular-music idioms has rendered their music “unpopular.” But unpopular with whom? Every year I play Satie’s Embryons desséches for some class or another, and the students always love it and want copies. His famous Gymnopedies are among the most recognizable pieces in the repertoire, widely appropriated and imitated. I have no trouble selling my analysis students Socrate, whereas sparking an interest in Wagner or Webern takes considerable explanation and effort.

Liz’s paper exposed two contradictions that didn’t strike her as sharply as they did me. One was that, after describing for pages how Satie drew on popular musics like ragtime and dance-hall songs for his compositional idiom, she mentioned that he went on to write in an “unpopular” style. You have to be pretty steeped in classical-music culture for this not to sound oxymoronic. Yet I spend much of my life writing about composers whose reliance on, and attempts to integrate, popular-music idioms has rendered their music “unpopular.” But unpopular with whom? Every year I play Satie’s Embryons desséches for some class or another, and the students always love it and want copies. His famous Gymnopedies are among the most recognizable pieces in the repertoire, widely appropriated and imitated. I have no trouble selling my analysis students Socrate, whereas sparking an interest in Wagner or Webern takes considerable explanation and effort.

On the other hand, Liz’s voice teacher considered Socrate a waste of time - not dramatic enough - and wondered why she bothered, while a couple of other faculty members admitted that they had trouble sitting through it. When I taught a graduate analysis course at Columbia a few years ago, I mentioned that Robert Orledge’s book Satie as Composer was probably the best in the Cambridge composer series, and the grad students gasped in disgust. You would have thought I was advising them to study the music of Lawrence Welk. So who is Satie’s pop-influenced music unpopular with? Musical academics, and classical-music professionals. They’re the ones who are so well-trained, whose expectations for classical music are so precisely calibrated, that Satie’s brilliance goes right under their heads.

For the other contradiction is that the paradigm shift that Satie set in motion has stalled, and never been completed. In fact, Satie and Schoenberg are the opposite extremes whose trajectories call the very notion of artistic paradigm shift into question. The idea is that an artist picks up on a new perception, uses a new method, it is resisted by audiences and all but the most perceptive artists for a generation, but eventually it becomes the foundation for a new and widespread understanding of music. One could say that that happened with Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Bartok, and other modernists. But while Schoenberg’s new paradigm became extremely popular with musical academics and “serious” classical-music mavens - precisely the group who don’t take Satie seriously - it never caught on with the general mass of music lovers. His paradigm shift grew impressive branches, but failed to sink very deep roots, and is now in danger of toppling. Satie’s paradigm shift earned him a permanent place in the periphery of popular culture that the academics never succeed in expunging, try as they might. (I’ll never forget Frank Zappa making a nonplussed rock ‘n’ roll audience sit through Socrate at the beginning of his final New York concert.) But, though permanent, Satie’s paradigm never grew outward into the mainstream culture of music. Consequently, 90 years after its composition, Socrate continues to arouse utterly contradictory impressions, a masterpiece to some and a hollow experiment to others.

The string of composers in love with Socrate’s understated pathos constitutes a virtual musical underground, and the composers whose own music Satie has influenced - starting with Virgil Thomson, extending through John Cage and William Duckworth, and by no means ending with myself - make up a confraternity whose music will forever embarrass and irritate musical academia. Satie infected us all with a virus - a lamentable lack of ambition, perhaps, an unwillingness to be pompous except in jest, an appreciation of pleasures too simple and obvious for school-room explication, a refusal to spend one’s life trying to get into the history books by outdoing one’s competitors. Even more than Cage, he’s a litmus test, and I can hardly imagine feeling comfortable discussing music over the long term with anyone who doesn’t “get” Satie. He did create a new paradigm, and a resoundingly potent one - but one so at odds with the continuing macho, power-grabbing one-upmanship of Western culture that perhaps only a total change in our mode of civilization would create a new environment in which one could declare it victorious.

Meanwhile, if I can ever someday return from the afterlife and find that my music is scorned by musical academia but stubbornly kept alive by generation after generation of music lovers devoted to it, just like Satie’s - I’ll feel like I will have been one of the blessed ones.

Postclassic Radio badly needed a fresh infusion, and it received one this week via a whole stack of new CDs that just arrived:

Corey Dargel: Less Famous Than You (Use Your Teeth)

Ingram Marshall: Savage Altars (New Albion)

Eve Beglarian: Tell the Birds (New World)

Warren Burt: The Animation of Lists and the Archytan Transpositions (XI)

plus a couple of welcome CD reissues:

Daniel Lentz: On the Leopard Altar (Cold Blue)

Lou Harrison: Chamber and Gamelan Works (New World)

All of these are now represented on the playlist by multiple tracks. Also there are a few pieces from the Cold Blue concert at REDCAT that I wrote about recently, and a major new work by Stephen Scott, The Deep Spaces, for bowed piano and soprano. This last one contains a long, oddly reorchestrated quotation from Franz Liszt's Années de Pelerinage. If you haven't listened for awhile because you'd heard everything, try it again!

UPDATE: At the risk of representing the song badly, here's the recording. Liz was having vocal problems that day and had been warned by her teacher not to sing, but she did anyway to avoid disappointing me. Given that, I thought it was a charming world premiere performance. And, since the poem's in public domain after all (see comments), here it is, made-up words and all:

Polyphiloprogenitive

The sapient sutlers of the Lord

Drift across the window-panes.

In the beginning was the Word.In the beginning was the Word.

Superfetation of to en,

And at the mensual turn of time

Produced enervate Origen.A painter of the Umbrian school

Designed upon a gesso ground

The nimbus of the Baptized God.

The wilderness is cracked and brownedBut through the water pale and thin

Still shine the unoffending feet

And there above the painter set

The Father and the Paraclete.The sable presbyters approach

The avenue of penitence;

The young are red and pustular

Clutching piaculative pence.Under the penitential gates

Sustained by staring Seraphim

Where the souls of the devout

Burn invisible and dim.Along the garden-wall the bees

With hairy bellies pass between

The staminate and pistilate,

Blest office of the epicene.Sweeney shifts from ham to ham

Stirring the water in his bath.

The masters of the subtle schools

Are controversial, polymath.

I’ve been absent. From about mid-April to mid-May at Bard, we start having student concerts every night and senior and moderation boards every morning, crammed in around teaching all afternoon. Senior and moderation boards are Bard’s idiosyncratic system for evaluating student projects just before graduation and at the point of declaring a major, respectively. It becomes common, in this final month before summer, to go in at 9 or 10 AM and not drag home until 9, 10, or 11 at night, and there are always student crises to deal with. President Botstein let drop the telling statistic recently that every student who’s ever committed suicide at Bard (none in the last five years, knock on wood) was a senior.

In addition, I’ve been up to my chin in the academic bullcrap of territoriality and politics. I am hardly an injured innocent bystander, but I do seem to be the faculty member always fighting for more diversity and variety in the department, and I am still pollyannaish enough at 50 to be surprised when that urge incites a fight. I attract the renegade and refugee students too individual to fit into the classical, jazz, and electronic programs, and every pop-music-bound student has me on her board - not because I know diddly about pop music, but because I’ll defend her right to do that in college. College is where you see self-described far-left-liberal professors casually expose the authoritarian streak by which they’ve determined that, past some arbitrary boundary their musings have brought them to, there are certain things that students should not be allowed to be taught. And this is at a really, really liberal college, so I guess I wouldn’t last a week at Indiana U., while at Yale I’d fry instantaneously like a strip of aluminum foil tossed into a microwave.

So any thought I could have expressed in the last month would have sounded like a complaint about a job that everyone agrees I’m lucky to have. I will content myself with the observation that I always preferred the atmosphere of a newspaper office to that of academia. At a newspaper, differences of opinion carry no negative charge. Opinions are what critics sell, and no critic wants to find that another critic is vending the same set of wares. As a music critic, I had far more reason to be threatened by someone like the poor late Rob Schwartz, whose opinions and interests were quite close to mine (and thus with whom I ended up competing for the same gigs), than by, say, some serialist complexity maven like Paul Griffiths or Andrew Porter. So you’d meet someone and start talking, find that they disagree with you about almost everything, and think, “Whew, that’s a relief.” And you’d have no qualms dealing with people whose views you found heinous, because their opposition made your uniqueness all the more valuable. I'm inclined to wish that academia could be a little more like that. Of course, I never went into a newspaper office five days a week like I go in to teach, and I’m sure those who do have a different perspective. As Tolstoy, I think, said, though I can’t find it anywhere, “Men are never so cruel as when they bind themselves into institutions.”

I hope to return to the world shortly.

Death is stalking me lately. I was greatly saddened to learn, via Alex Ross, of the death of my long-time Village Voice colleague Leighton Kerner. When I started there in 1986, Leighton proposed, by phone, to meet me at a concert, and added, with his usual self-effacing charm, “You’ll be able to recognize me - I’m overweight and badly in need of a haircut.” Alex says he wrote for the Voice from 1955; I had thought he was only regular from 1960 or ‘61, but I’m not going to check the archives to find out. Either way he had a few decades’ seniority over me, but he always insisted on dividing our duties to mutual advantage, and often gave me precedence when he didn’t have to. He was the only critic of his generation, as far as I kept track, who didn’t glorify the past in memory. He was fully capable of comparing an opera production he had just heard with a famous one from the 1950s, and admitting that the recent one was better. He was no purveyor of the elitist impression that classical performance, or composition, is endlessly headed down the toilet. He was a continual musical optimist, with no trace of condescension. Nevertheless, he provided one of my favorite Voice headlines ever when he reviewed a wretched late Menotti opera: “How the Mediocre Have Fallen.” He continued attending concerts seemingly seven nights a week even after the Voice lost its faith in classical music and cut his reviewing back to nothing. His wife worked for an airline and he could get free airline tickets, so he would fly to San Francisco, review an opera, and submit only a hotel bill for reimbursement. He was a mensch. He was a gentleman. He was a model for classical music critics everywhere.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog