main: January 2006 Archives

Probably no one but me gives a damn whether John Luther Adams’s music is postminimalist or totalist. As far as the specific terms go, I don’t give a damn either. But when I started surveying, in the 1980s, all the music that passed through New York (and, via recording, the rest of the country as well), I couldn’t help but notice that, among composers who were continuing and developing the minimalist aesthetic, there were two groups of qualities that almost always went together. The composers whose music was based on a steady beat virtually throughout, usually an 8th- or 16-th note pulse, also tended to use diatonic tonality, quasi-minimalist structures like additive process or permutation, mostly quiet dynamics, and acoustic timbres augmented by the occasional synthesizer. Those who used competing tempos, either simultaneously or interlocked somehow, tended to use more dissonant sonorities, more global large-scale rhythmic structures, mostly loud dynamics, and amplified or electric instruments such as guitars. For the former I appropriated the already-current but undefined word postminimalism; for the other the word totalism was provided. The distinction between the two styles was so striking and consistent that it would have seemed capriciously anti-intellectual, an act of scholarly irresponsibility, to have neglected to articulate my observations. Yet, judging from the comments I’ve received in subsequent years, the vast majority of musicians wish I had done exactly that: leave my musicological data on the ground where I found it.

Very few composers wrote music that combined different qualities from those two styles, but one major one who did was John Luther Adams. More often than not his tonality is diatonic, using a seven-note scale (often the “white” notes) with no pitch ever given precedence. Yet some of his pieces, like Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing and his piano cluster piece Among Red Mountains, have proved that he is just as happy to use the entire chromatic spectrum and a maximum of dissonance. His music for pitched instruments is almost always soft; his percussion music is mostly fortissimo. Nominally, his music falls square in the totalist camp because it almost always layers different tempos together. But some of John’s implied tempos are very slow, giving a new pulse only every 10 or 15 seconds, so that the effect seems more postminimalist, without the gear-shifting surface complexity you find in much totalist music. Even when he has 4-against-5-against-6-against-7 in each measure, the effect - achieved pianissimo with mallet percussion, celeste, and harp - is not so much one of tempo contrasts as of indistinct clouds of notes. No other composer from the minimalist tradition so resists being pulled into one definition or the other.

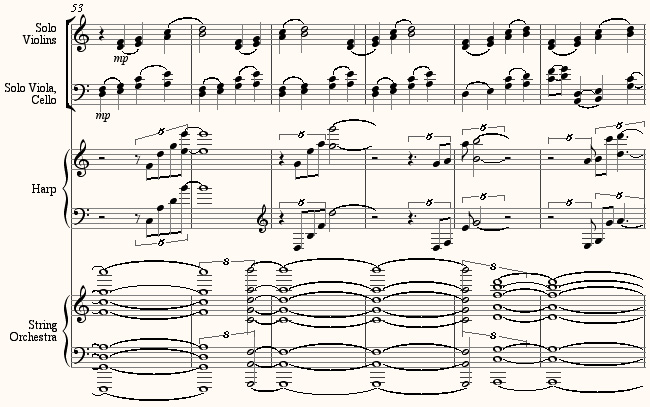

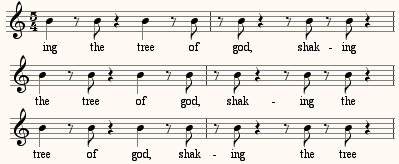

Dream in White on White (1992) has been surpassed in its ambitions by many of John’s works, but it became a prototype for one side of his ouput, and was a watershed in his development. Scored for string quartet, harp, and string orchestra, the piece opens with the string orchestra playing seven-note chords, changing to a new one every 2 and 2/3 measures. The solo quartet enters with chords changing every two measures, for a slow 3:4 rhythm. The harp then enters in four-note phrases in quintuplets, a new phrase every 1 and 3/5 measures. Thus the phrase rhythm is 20:15:12 by duration, or 3:4:5 by tempo, coming back in phase every 8 measures. At measure 53, the string quartet launches into what is marked as the “Lost Chorales,” outlining out-of-phase 4- and 5-beat loops between the two violins versus viola and cello. You can see those relationships, against the recurring harp and string orchestra pulses, in this example:

The next section has plucked notes in the quartet and harp outlining faster 3:4:5 rhythms in each measure, over a chord periodicity of 1 and 1/3 measures in the orchestra:

The chorales return, the string orchestra’s tempo increases, but in a final section the original tempo relationships resume.

You can hear Dream in White on White here. The work’s template has become the basis for at least two much larger works by Adams (and two of my favorites), Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing and In the White Silence. In the White Silence is in fact a magnificent expansion of Dream in White on White, stretched out to 75 minutes and with lovely solo lines for the quartet members. Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing achieves much denser clouds using mallet percussion and the entire chromatic scale. In each of these a large-scale process, implicit in Dream in White on White, is carried out more rigorously: an slow, stepped expansion of melodic intervals from 2nds through 3rds, 4ths, and on up to 7ths. (I kid John that when I start hearing tritones in his music, I know the piece is half over.) More aggressive aspects of totalism appear in John’s drum music, which hammers out more obvious intricacies at a more virtuoso tempo; but that’s for another day.

We have an MFA program in conducting, and I teach a course for it in 20th-century Orchestral Repertoire. I used to start chronologically with Busoni, Reger, and Holst, and work my way through the decades, but the class always broke down at some point into a discussion of the problems of programming 20th-century music for orchestra. The usual objections would arise: 20th-century music is more complicated than most orchestra subscribers can understand. It's more anxious and dissonant than they like. You have to have followed the course of 20th-century music to understand the recent stuff.

So now I teach the course backwards, 2005 to 1900, and I start with Sara's Grace by San Francisco composer Belinda Reynolds, which you can hear here. The performance is by Dogs of Desire, an orchestra that is a subset of the Albany Symphony, and that doesn’t market itself as an orchestra. The piece sets the whole discussion on a different footing. Turns out, some 20th-century music is difficult to figure out. Some of it depends on a familiarity with old styles. And some orchestra subscribers will reject Sara’s Grace just because the composer has the effrontery to not be dead yet - but then it becomes the audience’s problem, not the music’s. After all, anybody who can’t “get” what’s going on in Sara’s Grace might as well realize that music isn’t their thing.

Lovely article, painstakingly accurate in its description, about Meredith Monk by Ann Midgette in today's Times. It is overdue compensation for Ed Rothstein's scandalously contemptuous dismissal of a great artist in those pages after the premiere of Monk's Atlas in the mid-'90s.

Speaking of totalists, John Luther Adams turned 53 Monday; Mikel Rouse turned 49 today; Art Jarvinen turns 50 tomorrow (January 27). Had Mozart gotten a little more daring with his cross-rhythms, I might have noted his 250th as well. Those are the breaks.

Come to think of it, though, the party scene from Act I of Don Giovanni, with dances going in three meters at once, is quite audibly metametric. Consider him celebrated.

For whatever reason, I was never much drawn to the type of nested 3:2 and 4:3 crossrhythms that I described in my last metametrics post, but I did use it once, and could have mentioned it. In 1985, on the verge of turning 30, I was under some psychological pressure to write something ambitous. I decided on a big set of variations for two pianos, somewhat inspired by the two-piano tradition of Busoni’s Fantasia Contrappuntistica, Wallingford Riegger’s Variations, The Art of Fugue, and such huge solo piano variations as the Diabelli and Brahms’s Handel. (This was before Larry Polansky wrote his Lonesome Road Variations, which dwarfed mine.) My I’itoi Variations was a set of eleven variations on the “Black Mountain” song from the I’itoi cycle of the Papago Indians. I was very involved in collecting, transcribing, and analyzing American Indian music in those days, because I was attracted to its, um, proto-totalist rhythmic character - specifically the way it shifted back and forth among tempos.

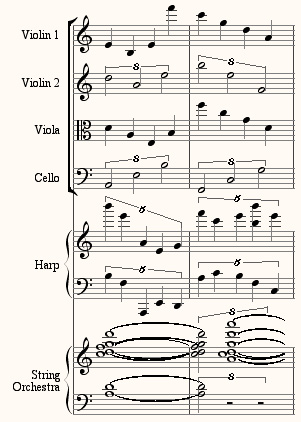

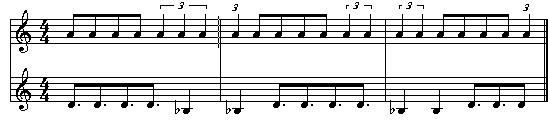

Another influence on I’itoi Variations (and on much of my music) was Beethoven’s Op. 111 Sonata - variations 1 through 6 were stormy and tense like Beethoven’s first movement, variations 7 through 10 were impersonal and calm like the second movement, and no. 11, in an attempted tour de force, went back through the first ten variations in reverse order. Variation 8 was based on a nested 3:2. The idea was simple. (I try to make all my ideas simple). There were two foreground lines, the bass line in piano 2 and the right-hand melody of piano 1, plus a line of quarter-note chords shared by both pianos. The bass was in dotted quarters, the treble in triplet quarters, for a 4:6:9 tempo resultant. I hoped the treble and bass would float in seeming unrelatedness to each other, though subtly mediated by the chords in between. Here’s a passage from the beginning of the variation:

and another from the end, where the treble and bass lines have doubled in tempo:

The bass line is the inversion of the theme, with the intervals doubled in size (a trick I picked up from Messiaen’s bird song music). I suppose it won’t much harm my reputation to admit that the changes of key are timed according to a descending sequence of Fibonacci numbers. Everyone who studied Bartok’s music had to try them once. This was back in 1985 when I had not yet heard of Mikel Rouse, Michael Gordon, or Art Jarvinen, and was blissfully unaware that they were using the same ideas.

Here’s the recording of Variation 8 from I’itoi Variations, played by the Double Edge duo - Nurit Tilles and Edmund Niemann, who premiered it at Cooper Union in New York circa 1990.

Next Monday night in New York my friend, classroom nemesis, and jazz harmony teacher John Esposito is involved in a concert in which will be premiered a couple of 1960 tunes by John Coltrane, recently discovered, that had never been recorded. The titles are "Out of a Dream" and "The Backbeat," the handwriting on the manuscript John recognized as Coltrane's, and since John is amazingly adept at historical styles (or so he keeps telling me), he was asked to harmonize and arrange them. He's playing with the Eric Person Quartet, of which he is a regular, but he's not sure where the gig is (jazz musician, you know...). Something to do with the Public Library, he thinks. I'll find out and give an update here. They look like really nice bebop tunes.

UPDATE: Oops, turns out the concert by Eric Person and Meta-Four is a private affair. My announcement has news value only. But you can get info at their website.

Composer and Sequenza 21 loiterer Steve Layton ran across this article pairing the two of us and discussing our gradual divergences from minimalism. It's the kind of composer-centered thinkpiece that I didn't think anyone wrote anymore except to praise Ligeti, Boulez, Adès, and that crowd that people praise to look cultured. Seems like old times.

As a performer - and I was a pretty good pianist in college, it’s the regret of my life that I didn’t keep it up - I never liked the feeling of complicated tuplets that couldn’t be expected to be played exactly right. I imagine you know what I mean: septuplet quarter-notes over a 4/4 measure, or an 11-tuplet with a couple of notes missing, and the composer says, “It doesn’t have to be exact, just make sure you end the phrase on the downbeat.” I never liked cheating, and I was so obsessed with polyrhythms that I didn’t want to fudge them, I wanted to feel them and feel secure playing them. Even with an ornamental quintuplet in Chopin, I worked to get it mathematically right. I had fallen in love with the three-against-four, two-bands-at-two-tempos section of the “Putnam’s Camp” movement of Three Places in New England, and at age 14 I said to the Universe, “Sir, it will be an honor to devote my life to replicating this effect.” So the fake polyrhythms, the little flurries that didn’t need to be accurate to achieve their goal, bothered me.

Judging from the music of my contemporaries, I wasn’t alone. The evolution of multitempo music in the wake of minimalism during the 1980s was an exploration of playable tempo relationships. When Conlon Nancarrow went this route, not relying on performers, he followed the arithmetical logic of numbers, going from tempo contrasts like 14:15:16 to 17:18:19:20 to 60:61. Those were impractical for the guys of my generation who wanted their bands to play multitempo music. Instead, they started out with simple relationships anyone could play, like 3-against-2 and 4-against-3, and then nested them. For example, take four drummers:

No. 1 plays a steady beat.

No. 2 plays a triplet against every two beats of 1.

No. 3 plays a triplet against every two beats of 2.

No. 4 plays a triplet against every two beats of 3.

This triply-nested 3:2 yields a pretty complex tempo resultant of 8:12:18:27, Drummer 4 playing 27 beats to every 8 by Drummer 1. This is exactly what Art Jarvinen does in one section of his Ghatam for sculptural percussion (1997), as you can hear here. He builds up the rhythm slowly, as a process, and doesn’t try to notate it, just gives instructions, because the notation would be needlessly complex.

This is also the same rhythm, though, that Ben Johnston used in the first variation of his “Amazing Grace” Quartet, No. 4 (1973). Going up one more 3:2, to 16:24:36:54:81, Ben did notate it, using different simultaneous meters to handle the overload. (You can hear that variation here, in the brand new recording by the Kepler Quartet.) Two variations later, Ben achieves (with great difficulty for the performers) a large-scale rhythm of 35:36, the same way one arrives at it in tuning pure pitch intervals: as the difference between a 9:5 and a 7:4 (or, rhythmically, 9 in the space of 5 and 7 in the space of 4). For Ben, as for Cowell in New Musical Resources, the methods of extending rhythm flowed by analogy from traditional ways of handling pitch, which was one of the core meanings of the word totalism in the first place.

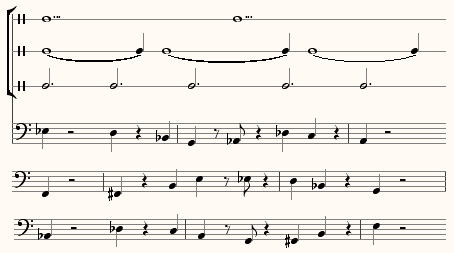

In fact, Ben (who was my postgraduate composition teacher) could be taken as one of the leading and underacknowledged pre-totalist composers, perhaps even the most influential one. It was he, after all, who, in 1967, translated a 12-tone song in pure tuning into analogous rhythmic ratios, and those ratios into a rhythm-only piece of conceptual theater that was to be beaten on the outside of a piano with any available mallet-like objects. Titled Knocking Piece, the work was played all over the Midwest in the ‘70s, and was an obligatory virtuoso showpiece for young percussionists. It always had two tempos going at once, in ever-changing ratios determined by the 12-tone row the song had been based on:

The equal signs between measures indicate that the same pulse continues across the barline at that point. (No recording I know of available, unfortunately. If you know something about tuning, you can figure out the original pitches from these rhythms: taking the first as C, it continues G, E, B, D#, A#, F#...) Ben’s reputation never took off on the East Coast to nearly the same extent. But insofar as some of the totalists had been educated in the Midwest, Knocking Piece may well have been a seed that quietly (or rather, noisily) blossomed in the music of 1980s New York.

The piece that went furthest in exploring this kind of performable tempo layering, as far as I know, was Michael Gordon’s Four Kings Fight Five of 1988. Scored for three winds, three strings, percussion, electric guitar, and synthesizer, the work starts out with a melody that pits quarter-notes against dotted quarters in 6/4-slash-12/8, because the other rhythms (the four kings who fight against five) are going to be drawn from this concurrent contrast. The pounding opening, with much unison, is the part most relevant to the piece’s dedication, which is to Glenn Branca - of interest to those of you who may doubt whether the Branca/Chatham artrock of the time had any immediate connection to totalism. (Branca produced Gordon’s first record, as well.)

At 3:08 (three minutes, 8 seconds) into the recording of Four Kings Fight Five, the music pauses, and a rhythmic continuum starts to build up that will proceed through eleven different tempos, as many as seven of them at a time. The tempos are represented by the following note values, repetitively articulated:

quintuplet 16th-notes in the space of 6 (a dotted quarter)

triplet 8th-notes

dotted 16th-notes

8th-notes

triplet quarter-notes

dotted 8th-notes

quarter-notes

quarter-notes tied to 32nd notes*

dotted quarter-notes

half-notes

half-notes tied to 16th-notes

*(Gordon notates the quarter-notes tied to 32nd notes as dotted 8ths in a tuplet over the three 8ths of a dotted quarter beat, but it works out the same. Don’t worry about it.)

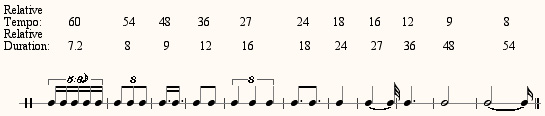

The eleven available pulses are given here with the ratios of their relative tempos and durations:

These ratios can be seen as analogous to pitch. If we take the quarter-note as C and the triplet quarter as G, we get the following “harmony” of tempos:

A - 60 tempo - quintuplet 16th-notes in the space of 6

G - 54-tempo - triplet 8th-notes

F - 48-tempo - dotted 16th-notes

C - 36-tempo - 8th-notes

G - 27 tempo - triplet quarter-notes

F - 24-tempo - dotted 8th-notes

C - 18 tempo - quarter-notes

Bb - 16-tempo - quarter-notes tied to 32nd notes

F - 12-tempo - dotted quarter-notes

C - 9-tempo - half-notes

Bb - 8-tempo - half-notes tied to 16th-notes

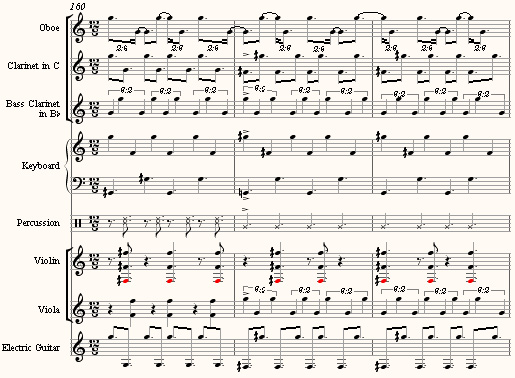

Note the self-inversional character of this harmony, except for the fastest A-tempo. At the work’s most complex point (long before the halfway point, at about 5:47), there are seven tempos going at once:

You can sort of see that everyone else is playing off either the quarter-note beat or the dotted-quarter beat, which are unified in the keyboard part. The viola and bass clarinet play triplets off the quarter-note beat. The violin, less obviously, is playing 2 beats to every 3 dotted-quarter beats. The oboist, poor dear, is having to play 4-against-3 to the dotted-quarter beat, or 16 even pulses over three measures; actually twice the tempo of the violin, but not lined up in rhythmic unison with it. Here six of the lines are cued to the dotted quarter beat and three to the quarter-note beat, but one assumes that elsewhere the ratio is four lines against five, as per the title.

From here on, the piece gradually floats into a more static continuum, which became typical of Michael’s music about this time. At 19:22 a viola starts up in free rhythm over the throbbing G major continuum underneath, and at 20:56 a snare drum rhythm in military time joins it, and the piece dies away. You can hear Four Kings Fight Five in its 23-minute entirety here; the rhythmic points I’ve been making are all illustrated within the first seven minutes.

Please don’t get too exercised over whether you “like” the piece or not. Frankly, I don’t find it, overall, one of Michael’s most compelling works, though I certainly love parts of it - I somewhat prefer Thou Shalt!/Thou Shalt Not!, Yo Shakespeare, Trance, and the Van Gogh Video Opera, among others. The question is not whether you “like” it, but whether you understand what it offered in terms of multitempo composition. In that respect it was not only remarkable for 1988, but offered possibilities that have still not been fully explored since.

What’s common to all three pieces, by Jarvinen, Johnston, and Gordon, is that the performers achieve a remarkable degree of rhythmic complexity - a true “harmony of rhythms” in Cowell’s sense - by selectively listening to some performers within the ensemble whose pulses they play off of, and having to ignore others. The ability to maintain a 4-against-3 rhythm over a steady-beat reference point, and the relative impossibility of securely maintaining a more difficult 27-against-16, is the same in rhythm as it is in pitch: a perfect fourth (4:3 pitch ratio) is easy to tune, a Pythagorean major sixth (27:16) extremely difficult. Gordon could still have gone a little farther than he did by factoring in more 5-against-4 rhythms, both as quintuplets and as quarter-notes tied to 16th-notes. I have sometimes succeeded in getting a class of students to clap 25-against-16 by conducting a quarter-note beat and having half clap quintuplet quarters while the other half clap quarter-notes tied to 16ths. Gordon goes only so far as a quintuplet over the dotted-quarter beat. I don’t know of a piece that went further in drawing so many competing rhythmic layers at the same time in a large, live-ensemble texture. It wouldn’t surprise me if Gordon’s Trance does, but I haven’t seen the score.

Via Mary Jane Leach, here's a Honda ad that brings the early '60s avant-garde into the mainstream at last.

UPDATE: Here's all the info on the ad, including the composer, Steve Sidwell.

Pianist extraordinaire Sarah Cahill, whose browser somehow won't let her interact with Arts Journal comments pages, nevertheless chimes in on the dynamics issue:

Leo Ornstein... was an excellent pianist himself, and wrote fabulously for the piano. But most of his piano scores have absolutely no dynamic markings whatsoever. He believed that it was the pianist's responsibility to come up with dynamics in the process of interpretation. It's so interesting, because there will be a passage which to one person is a climax, to be played forte, and to another person it will be an opportunity to back off and have it be more powerful as a pianissimo passage. So his scores can be played in a variety of ways, and it's fascinating to hear different performances.

...[W]hen a piece leaves dynamics out, it makes us as performers explore it in an entirely different way. We can't rely on superficial expression (playing dynamic markings as notated), we have to dig deeper and get to the heart of the piece to figure out what's going on, how to best interpret it, and how dynamics figure into that interpretation. It can be a more satisfying experience.

Not that everyone should compose the way Ornstein did - but if someone's imagination works that way, why shouldn't he be allowed to do it? How did conformity become such a cherished attribute among composers? And I can't resist re-quoting the following note that Ellen Zwilich appended to her Lament for piano of 1999, a warning that Chopin would have found ludicrously obvious, but that today's notation neuroses have made necessary:

Throughout, whether the passage is marked liberamente or not, the performer should feel free to 'sculpt' the rhythm and dynamics for expressive purposes in order to give a spontaneous, improvisatory quality to the piece. It would be ideal if no two performances were exactly alike.

For years I have fought within musical academia for the right (for myself and students) to minimally notate dynamics, to not use dynamic contrast as one of the ways of structurally articulating a piece if you don't want to do so. I have seen student works cancelled or excluded because they were soft (or loud) throughout, or because within a certain range they wanted to leave dynamic nuances to the performer. I have paraded around with copies of manuscripts by Bach and Rzewski that are devoid of dynamic markings, to prove that their absence does not indicate musical idiocy, and I have argued myself blue in the face to composers adamant that dynamic particularity is synonymous with "professionalism." But such a discussion came up on Sequenza 21, and Peter Gordon, of Love of Life Orchestra fame back in the '80s, gave an eloquent rationale for dynamic reticence that had never occurred to me:

I don't know whether dynamics is so much about compositional contrast, but more how much you want to signal for the listener within the composition. More static dynamics allow the listener more freedom and offer a contemplative space to explore other parameters, often at the listener's own pace. More active and extreme dynamics can involve the listener on a more physiological level, which can be good or bad. Overactive and domineering dynamics can, if cynically used, run the danger of becoming - like the work of Steven Spielberg - emotionally pornographic.

UPDATE: One more point in response to some comments, because I hadn't planned on getting into another notation argument - the whole issue has come to disgust me because of the neurotic, historically myopic concensus that has come to exist among 95 percent of today's composers.

I have found a tremendous difference in responses to notation between performers who specialize in 20th-century music and those who play mostly Classical/Romantic repertoire, and far prefer the latter. One of my colleagues intimidates students who hand her music that is "deficient" in dynamic markings by saying, "This is the way they'll play it:" - and then she plows through the music at the piano with the most unimaginative uniformity. In my experience, that can indeed be true with 20th-century specialists, who have been trained to react to the printed page with the literalness of a computer; but hand the same music to a Beethoven specialist, and they'll do what they do with Beethoven, interpret it and invest it with feeling, coming up with the most delightfully varied and creative responses.

Whenever possible I prefer to work with conventional classical musicians. If I know in advance I'm writing for 20th-century specialists, I try to dutifully nail down every tiny nuance, as if I were making electronic music, because I know they're not bringing any creativity to the table. The process is so much nicer, though, when the performer comes with her own human and musical instincts. Pianist Sarah Cahill is such a creative performer, even if she does specialize in 20th-century (but recent, not the academic stuff) - and the way she plays my Private Dances is more beautiful than I imagined them, and surprising in some cases. Thank goodness I didn't load the pages down with hairpins, slurs, accents, and precisely calibrated tempo changes that would have kept her from following her muse.

For the other 31 reasons why I think most composers have their heads up their asses where notation is concerned, I once again refer the reader to my article The Case Against Over-Notation.

The venerable Jerry Bowles of Sequenza 21 reminds me that I should be attending to my own PR, and I need the reminder. It never becomes a reflex, for some reason.

But three members of the Da Capo ensemble, joined by myself and my son Bernard, will perform my new piece The Day Revisited this Tuesday, January 24, at 7:30 PM at the Knitting Factory, 74 Leonard Street. It's my first NYC gig in a year or two, I guess, and if Stockhausen can perform with his son Markus, I can perform with mine. Flutist Pat Spencer and clarinetist Meighan Stoops had asked me to write them a microtonal piece, and after having their heads examined I complied with a work in a 27-tone, just-intonation scale, for flute, clarinet, two keyboard samplers, and fretless bass, this last played by my son, who's pretty inured to my tunings by now. Though slow and mellow it's a damned difficult piece because of the tunings, but I'll just be sitting there playing chords. Also on the program are works by a bunch of famous people: Eric Moe, Martin Bresnick, Derek Bermel, Michael Gordon, Gene Pritsker, and Philippe Hurel, which I guess means I'm a real composer too. Da Capo's calling this a world premiere - the only other performance was here at Bard, and we had technical problems then that we're not going to have this time, knock on wood. Call 212-219-3006 and bother the Knitting Factory about it.

Pianist extraordinaire Sarah Cahill will also play two of my Private Dances at REDCAT in Los Angeles on February 18, but I'll remind you about that later.

I've had a hell of a time with my microtonal music lately. I've outgrown the samplers I've been using for the last 12 years, and am at the epicenter of a complete technological overhaul. Nowadays everything is software-based, so I've acquired Kontakt 2, Max/MSP, and Scala (newly available for the Mac) in an attempt to get better sounds and more feasible playability in my microtonal stuff. For years I've taken a lot of crap from people who find my electronic timbres amateurish, which has always seem unfair, since I'm using the most expensive microtonal samplers I can afford. So what if I use the sounds that come with the box? - I make up my own pitches, and everyone else uses the pitches that come with the box, which strikes me as a worse infraction. If I can get Kontakt to work (still touch and go at the moment), I'll reorchestrate as much of my early music as I can stand to. Suggestions on how to get good sounds with microtonal-friendly software are always welcome. It's a huge barrier between me and the continuation of my career at the moment. As for The Day Revisited, I usually don't write microtonal music for acoustic instruments because the performance hurdles are just too great, but I was asked, and they're working their butts off.

While I'm blowing my own horn here, Christopher DeLaurenti has officially given my book Music Downtown its jaunty first review.

I am hugely chagrined to learn from the latest issue of Signal to Noise that composer Luc Ferrari died last August 22 and I never even heard about it. Along with Henri Pousseur and Bruno Maderna, Ferrari was one of those figures peripheral to Darmstadt serialism who seemed so much more intriguing than the central protagonists. I can’t say I ever quite understood Ferrari’s music - in fact, that was what was so damned interesting about the three of them, whereas what Boulez, Stockhausen, and Nono were doing was so obvious, so minutely explained and explainable. The signal piece for Ferrari was, of course, Presque Rien No. 1, a 1969 piece of musique concrète of which I find this decription at the Other Minds website:

I am hugely chagrined to learn from the latest issue of Signal to Noise that composer Luc Ferrari died last August 22 and I never even heard about it. Along with Henri Pousseur and Bruno Maderna, Ferrari was one of those figures peripheral to Darmstadt serialism who seemed so much more intriguing than the central protagonists. I can’t say I ever quite understood Ferrari’s music - in fact, that was what was so damned interesting about the three of them, whereas what Boulez, Stockhausen, and Nono were doing was so obvious, so minutely explained and explainable. The signal piece for Ferrari was, of course, Presque Rien No. 1, a 1969 piece of musique concrète of which I find this decription at the Other Minds website:

By 1970 he had completed Presque Rien No. 1, a kind of musical photography, in which unassuming ambient sounds of a small village in Yugoslavia, recorded throughout a long day, are telescoped by means of seamless dissolves into a 21-minute narrative in which no apparent “musical” sounds are included.

That’s more detail than I’d ever gotten before, and I had never understood exactly how Ferrari seemed to crowd so many sounds into a 20-minute tone poem. Many of his concrète pieces are similar, but he also wrote strange, more serial-sounding instrumental works, and seemed obsessed with the naked female form, which figured on his CD covers and several titles. I kept thinking something would happen to bring him out into the open, and I was excited when, in 1991, he made a seeming comeback and began to put out CDs after a long absence from public visibility. And now he’s dead at 76, with my having been little wiser about him than I was in 1980. I hope some critical dialogue arises around him, brushing away the unfortunate clouds of serialist mystique that obscured the movement’s less dogmatic masters.

Thousands of people consider Elliott Carter a great composer. He’s won two Pulitzer Prizes, and gets performances and even retrospectives out the wazoo. He is assured his chances with posterity, regardless of what I do, or what any other individual does. Aside from the royalties he’s missed by my not buying all of his recordings, twenty years of my expressing misgivings about Carter’s music has not caused five dollars’ worth of harm to his finances or his career. If I really thought any of my ideas could truly do harm to Carter, I would be more reticent about expressing them. I have nothing personal against the man. In the case of far less well-known composers, however, it is possible that a negative review from me might do real damage.

This is why, as a Village Voice critic, I always maintained an ethical policy of only writing negative reviews in cases in which the support given the composer (or performers) was sufficiently compensatory. I have a vague idea that this reflected Voice policy in general, though I can’t specify how I was aware of that. For instance, if Lincoln Center or BAM presented a concert, all gloves came off. Large-scale institutional support for a composer, together with the attendant publicity machine, requires objective criticism as a counterweight. (As Virgil Thomson said, music criticism “is the only antidote we have to paid publicity.”) Many voices would weigh in in such a case, and it was incumbent on each of us to register our opinion as to whether the composer involved merited such grandiose support. The smaller the venue, the less incentive there was to review a composer who failed to impress me. If I heard a concert I didn’t like at Roulette, or the Performing Garage, or some other small space, I would usually simply not review it. There was no reason I could see to draw only negative attention to an artist who, otherwise, would have received no attention at all.

There were exceptions. Sometimes one artist I didn’t care for would perform on a concert otherwise well worth reviewing. In a couple of cases, artists pestered me so urgently for a review that I had to take them at their word and assume that they would prefer honest disapproval to no public reaction at all. Occasionally I would attend a concert I had expected to like, be very disappointed, and not have time to find another concert before my next column was due - thus the negative review appeared perforce. In general, though, I tried to avoid giving negative reviews to artists who were having a hard time making it and getting very little institutional support; if I couldn’t find anything redeeming to say about their work, I would simply ignore them. I would, however, review artists whose work I didn’t like if they were famous and/or getting programmed at major venues. For one thing, my conscience was always clearer if I wasn’t the only critic commenting. Of course, at the Voice I had a luxury few publications provide, of being able to pick and choose what concerts I wanted to write about.

All this is to explain why I am going to impose on the comments that come in response to this blog the same policy I applied to my career. Most of the composers I write about here are not regularly written about by anyone else. Their music is not well-known even among the rarefied circles of new-music connoisseurs. Some of them have little keeping them in the public eye beyond my enthusiasm and that of their immediate colleagues. My advocacy alone is in little danger of bringing them to an undeserved level of worldly success. All of them have in common that I find their music important or interesting in some way or other, even if the musical examples I cite may sometimes be chosen more to illustrate a technical point rather than to prove their attractiveness. I would be ill serving these composers if, in my advocacy, I peripherally left their music open to harsh criticism by every malcontent who chooses to read my blog. Nor should they be held to account for the way I present their work - they themselves might present it quite differently. If I’m just demonstrating technical features, then whether you like the music or not is truly neither here nor there.

If I provide a musical example that you don’t like, you are perfectly free to express your opinion of it on your own blog, at some other forum, or at any other web site. I will not, however, publish that negative opinion here. Most of the negative opinions of music by my peers that I’ve expressed during my career were elicited by the incentive of money, because criticism was my livelihood. My reputation as a dependable critic required the trust of my readership, which demanded honesty on my part, entailing the occasional negative review. Few who respond to my blog have similar incentives. If for some reason you are particularly desirous that I become aware of your unfavorable reaction to music I post here, feel free to drop me an e-mail. But I will not subject the composers I champion to the sting of harsh comments by the random public of internet passers-by. Besides, I submit that it is rather stupid to sign your name to a public, Google-able, harsh disparagement of the music of a total stranger without having any professional reason to do so. In that sense, I am protecting you from your own baser impulses.

As for the objections that were voiced concerning Mikel Rouse’s Quick Thrust, most of them had to do with the allegedly stiff nature of the drum playing. I simply do not acknowledge this as a deficit. For one thing, the piece dates from 1984, at the very beginning of the classical attempt to incorporate rock materials into a classical structure, and indeed, at the very beginning of Mikel’s career. More generally, new music has been largely an attempt to arrive at a music in between classical music and pop music. This compromise has met with violent resistance on both sides: from the classical musicians who refuse to take music with pop elements seriously, and from the pop fans who refuse to countenance music that uses drum sets but is played from a score, and played faithfully to the notation. Believe me, over a 23-year career as a critic, I have received a couple of billion messages to indicate that most musicians hate the music I advocate for one reason or the other. Most musicians never wanted an in-between music, only more of what they already had, and they will never, ever give the in-betweeners any credit for trying. Many pop fans are especially dogmatic in their unalterable position that a piece that uses trap set MUST HAVE THE LOOSE, DYNAMIC ENERGY OF ROCK or the heavens must fall. For all that Mikel has come a long way since 1984, I, as a classically-trained and -raised musician, prefer the tight drumming-to-structure relationship in Quick Thrust to more typical rock drumming. You do not. Your opinion is noted, once again. Clearly, this music is not for you. I recommend not listening to it. That does not mean, however indignant you are in your opposition and however ardently you feel otherwise, that it is bad music. It simply doesn’t.

I thought I’d put up a more detailed example of an early totalist piece, to show precisely how composers started breaking away from minimalism in the early 1980s. Mikel Rouse’s Quick Thrust of 1984 is a work that both reaches back into minimalism’s most formalist concerns and also forecasts ideas that would later become widespread. For one thing, it was one of the first fully notated pieces for a pop instrumentation, written as it was, like most of his music of the ‘80s, for his rock-instrumentation quartet Broken Consort, consisting of soprano sax, electric keyboard, electric bass, and drum set. Secondly - it’s a 12-tone work. The composers whose work would later be called totalist loved minimalism’s formalism, hard-edged textures, reduced range of materials, impersonality, and amplified ensemble concept, but were not much enamored of its pretty, diatonic tonality (at least as manifested in the work of Reich and Glass). Few turned to 12-tone technique, nor did Mikel ever repeat the experiment as far as I know, but Quick Thrust is a bona fide piece of 12-tone totalist rock - perhaps the only one.

Thirdly, Quick Thrust is an example of music drawn from Schillinger technique, for Mikel studied with a Schillinger specialist when he came to New York in the early 1980s. Today Joseph Schillinger’s technique is more widely known by reputation than example, but in the 1930s and ‘40s, it was particularly picked up by Tin Pan Alley composers as an aid to churning out music in a hurry. Gershwin studied it; so did, later, Earle Brown. (Schillinger’s hefty two-volume exegesis of his methods is forbidding, but quite clear if you persevere. It tends to introduce a new principle and work its way up to a musical example, and is actually easier to follow if you kind of start with each musical example and work your way backward to the principle.) The technique is based in a faith in the ability of number systems and arithmetical techniques to generate musical forms of innate aesthetic attractiveness, and some of its devices had been presaged in Henry Cowell’s precocious book New Musical Resources.

One technique in particular resonated with Cowell: generating rhythms via what Schillinger called the interference of periodicities. This meant repeating several rhythms of different lengths, and using the sum of their resultant attacks as a melodic rhythm. For instance, the pattern made by the simultaneous repetitions of a dotted 8th-note at the same time as a repeated quarter gives the resultant 3-against-4, the rhythm known by the mnemonic device “PASS the GOD-damned BUTter.” Since only one rhythmic value is used for each rhythm, this is an interference of monomial periodicities. In Schillinger technique, one could also have a rhythm of two notes (say, quarter + 8th) against another two note rhythm, creating a binomial periodicity. The song “Fascinatin’ Rhythm,” in fact, starts with an interference of a sexonomial periodicity (8th, 8th, 8th, 8th, 8th, quarter, totaling 7 8th-notes in duration) against a 4/4 meter. (That Gershwin wrote the song long before studying Schillinger suggests why he was drawn to the technique.)

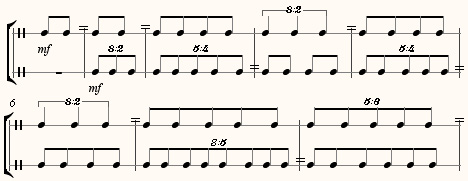

Quick Thrust is entirely a product of interferences of monomial periodicities. Mikel rather fanatically derived all of his rhythms based on periodicities of the Fibonacci numbers 2, 3, 5, and 8. Every rhythm was either the result of the sum attacks of repeated notes of these durations, or else of a larger rhythmic unit divided into 2, 3, 5, and 8 parts. For instance, the bass line was frequently the result of dividing a duration of 30 8th-notes into 2, 3, and 5 equal parts:

Note that the 12-tone row is run through the eight-note rhythm in a phasing relationship, the pitch row and rhythm row returning to their original relationship every 24 notes. This is, of course, a recurrence of medieval isorhythmic technique, in which a pitch row (called a color) and a rhythm (called a talea) go out of phase with each other. The practice was the structural basis of the 14th-century motet, died out around 1450, and was resurrected again by Messiaen in the first movement of his Quartet for the End of Time (1941) and Study No. 7 by Conlon Nancarrow (early 1950s). It has appeared in several totalist works, my own Desert Sonata (1994) included.

The upper lines of Quick Thrust, also treated isorhythmically, tend to be drawn from patterns of recurring small durations, such as this line made up from the summed attacks of notes 3, 5, and 8 8th-notes long:

At the beginning of the piece the entire 12-tone row is heard as an introduction, upon which the bass line enters, and then the keyboard and saxophone, creating a texture of three Schillinger rhythms at once, the same tone-row cycling through all three:

Notice that the high hat rhythm follows that of the keyboard, basically doubling it, and that the drums follow the bass line. Mikel never used any other transposition or form of the row (no retrogrades or inversions), for an effect that has always reminded me of the second movement of Stravinsky’s Threni, where he does something very similar. Others will be reminded of the young Steve Reich in the ‘60s, using the same row form over and over until his teacher Luciano Berio finally asked, “Steve, if you want to write tonal music, why not just write tonal music?”

And now, ladies and gentleman, you can hear Quick Thrust in its five-minute entirety here. (By the way, there has never been a score to Quick Thrust - Mikel gave me the individual instrumental parts for his music from those years, and I’ve had to assemble the scores myself.)

I emphasize that this piece represents one of the initial starting points of what has been called the totalist, or metametric, movement. Like so much postminimalist music of the early ‘80s, it is minimalist compositionally, but not perceptually. Its repetitiveness is intricately disguised. Its strict processes are not linear but global, real to the composer but not heard by the listener. (Many movements of Bill Duckworth’s earlier Time Curve Preludes are similar in this respect.) Quick Thrust is a fantastically clear example of a certain kind of rhythmic and structuralist thinking that was pervasive, “in the air,” in the mid-1980s among a certain kind of minimalism-impressed-but-not-quite-impressed-enough composer - not characteristic of the totalist movement as a whole, but quite typical of several months in 1983/84.

This kind of intense structural fanaticism was soon left behind. Number patterns remained in use in the works of many composers, such as Michael Gordon, Art Jarvinen, Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca, Ben Neill, Evan Ziporyn, Diana Meckley - but usually in textures of more intuitive freedom. The interference of periodicities became the basis of the fifth movement of Chatham’s An Angel Moves Too Fast to See, at least part of Branca’s Sixth Symphony “Devil Choirs at the Gates of Heaven,” and several pieces of my own in the ‘80s, most concentratedly my 1987 piano piece Windows on Infinity - though my interest was always in longer time stretches and larger prime numbers, with events occurring every 53 8th-notes, every 71, every 103, and so on. When Mikel heard a concert of my music by Essential Music in 1989, and I heard his Quick Thrust and other Broken Consort works soon afterward in 1990, we got together, started talking, and realized that we had been on the same track. You could look it up.

Subsequently I wrote about Quick Thrust and other works with similar rhythmic tendencies in an article in a 1994 issue of the academic journal Contemporary Music Review. Possessing entire file cabinets full of unpublished scores by composers of my generation, I could write another article like this every month. But very few people have seen that article, and articles in academic journals pretty much disappear into libraries, to be scoured at rare intervals by the occasional researcher. I’ve got tenure, I don’t need any more resumé lines, thanks. Now that I can put both score examples and recordings on the internet, I would far rather publish here, where I am am actually read. And since few people who weren’t immediately involved in the scene were aware of techniques used by the music I’ve spent my life writing about, I hope that with this method of presentation I can bring the underground history of the 1980s and ‘90s out into the open and help the world catch up. Does it sound like I’ve finally begun that book on Music After Minimalism that I’ve been threatening for years? I guess I have.

The most frequent and bitter complaint I've gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I've just learned - over the internet, with the rest of the world - that a paperback edition is finally appearing this coming May. No price has been set yet, but I figure this should bring it down to no more than £150,000,000,000, or, in US dollars, approximately the monthly salary of an Exxon/Mobil CEO. So hold on a few more months and you'll save.

The most frequent and bitter complaint I've gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I've just learned - over the internet, with the rest of the world - that a paperback edition is finally appearing this coming May. No price has been set yet, but I figure this should bring it down to no more than £150,000,000,000, or, in US dollars, approximately the monthly salary of an Exxon/Mobil CEO. So hold on a few more months and you'll save.

I wish I could also correct a few of the errors in the book, most of which have been helpfully dredged up for me by subsequent Nancarrow scholar Margaret Thomas. The most egregious is that, in the charts that show the structure of Nancarrow's canons, Study #43 is inexplicably missing. There are also some pitches wrong in Example 8.33, which analyzes the bass line of Study #41b. Maybe I can put together a list of errata for the web. Even so, there are fewer errors in the book than there were in Thomas Adès's pissy review of it in the London Times Literary Supplement.

David W. Galenson’s new book Old Masters and Young Geniuses (Princeton University Press) is an apparently unprecedented study of the relationship of age to creativity. Galenson, an economist with a yen for painting, charts out for many famous painters the age at which each one peaked creatively. His method, brilliant in its empirical objectivity if rather obvious in hindsight, is to rate each painting by three criteria: its top selling price, how often it is included in academic art textbooks, and how often it is included in retrospectives of the artist’s work. He then correlates the paintings that rate highest in these regards with the ages at which they were painted. Thus we find that the most valuable and oft-cited of Picasso’s paintings were executed between the ages of 20 and 29, and the most valuable of Cezanne’s between 60 and 69. We even find that entire movements were populated by painters who tended to do their best work at certain ages. For instance, the abstract expressionists tended to peak later in life:

Mark Rothko, age 54

Arshile Gorky, 41

Willem de Kooning, 43

Barnett Newman, 40

Jackson Pollock, 38

than the pop artists:

Roy Lichtenstein, 35

Robert Rauschenberg, 31

Andy Warhol, 33

Jasper Johns, 27

Frank Stella, 24

Galenson’s next step is to correlate these ages with everything that the artist ever said, or that is known, about his working methods and aesthetic approach. He comes up with an amazing consistency of correlations, and bases on it a theory of two creative types. While one might wish for a less ambiguous terminology, his terms at least possess the virtue of being non-evaluative: the Experimental Artist and the Conceptual Innovator. As detailed in dozens of examples, the Conceptual Innovator:

* tends to peak in his 20s or early 30s;

* produces one or two or three works well-known as his greatest or most influential;

* tends to do a tremendous amount of sketching and planning, finally executing the final work with great speed and a sense of finality;

* relies heavily on research, borrowing, and quotation; and

* achieves a conceptual redefinition of the art form in question without necessarily reaching new depths of expression.

By contrast, the Experimental Artist:

* tends to peak in his 40s or 50s if not later;

* develops steadily throughout his career, producing a consistent body of work in which no particular painting stands out as the greatest;

* figures out what he’s trying to do in the process of painting, without following (at least successfully) a preconceived plan, and often continually revising afterwards;

* takes his material from personal experience or the environment around him; and

* expresses something deeply true about his world without necessarily transforming the genre he works in.

Picasso was the quintessential early-blooming Conceptualist, Cezanne the exemplary Experimentalist. Cezanne said, “I seek in painting”; Picasso replied, “I don’t seek, I find.” Cezanne’s method was described thusly:

the ultimate synthesis of a design was never revealed in a flash; rather he approached it with infinite precautions, stalking it, as it were, now from one point of view, now from another... For him the synthesis was an asymptote toward which he was forever approaching without ever quite reaching it...

Picasso’s career, by contrast, was a series of discrete discoveries; he made over 400 preparatory sketches for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, quickly brought the final painting to his image of perfection, and it became his most famous work.

Galenson has no expertise in music, he tells me, but he applies the archetypes as well to poets, novelists, and film directors. Conceptual Innovation can be seen in the reliance on quotation of T.S. Eliot in The Wasteland (his most influential work by far), Ezra Pound in his Cantos, Andy Warhol in his famous prints, and (my example) the collages of John Zorn. By contrast, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Robert Frost drew heavily on their environments and continued to develop their technique until the end. The Experimentalist Twain often found that his books would not progress with the plots he had planned, and he would have to take time away from them until they worked themselves out. Conceptualist E.E. Cummings was criticized for never having gone beyond the brilliant innovations of his earliest poems. Dickens, an Experimentalist, gave us pictures of life in Victorian England that are truer than history; Melville, relying on books on whaling rather than personal experience, turned our conception of the novel upside-down with Moby Dick at the age of 31. Conceptualists do not always receive early acclaim - Moby Dick was a financial disaster, not appreciated until after Melville's death. The two types need not lack affinity. The poet Robert Lowell, who did his greatest work in his last years, was a signal influence on Sylvia Plath, who pre-empted her own late period by committing suicide at 30. And so on and so on, with a wealth of well-chosen personal statements of artistic process.

I suggest applying this typology to composers with some caution. The issues may be different, who knows? But certain examples will spring to mind. We have some Conceptual Innovator composers with explosive early careers, forever best known for one or a handful of precocious early works: Stravinsky, Antheil, Cowell, Messiaen. Easier to call to mind are those Experimentalists who developed their music later in life, with no particular work standing out: Shostakovich, Sessions, Partch, Carter, Feldman. I’m tempted to type Ives and Copland as conceptualists, but the later date of some of their best works militates against it. Perhaps music has some aspects of technical acquisition and performance vicissitudes that require some alteration of the time line. It'll be fun to do some study and find out.

In any case, Galenson’s book has achieved three objectives. It has created a new form of the always-appreciated parlor game of dividing artists into two types; it has drawn, with the most incisively empirical methods, two contrasted views of the creative process, with surprisingly bundled groups of attributes, deserving of voluminous further study; and it has proven irrefutably that the curve of creative potency over a lifetime differs tremendously for different individuals, with certain pattern types evident. We have new grounds for believing it naive to assume that the later work of a famous young artist will continue to be as profound, and likewise, to believe that an artist who hasn’t evinced signs of greatness by age 40 may well still do so. Galenson has established, with an economist’s objectivity, that these patterns vary with creative type; the evidence his fine book provides will help us gauge our expectations and perceptions accordingly.

Just heard a conductor from the Wichita Symphony (whether the conductor, I didn't catch) participate in the NPR word puzzle show. The host asked him what Wichita was playing this season. His reply: "Oh, everything from Mozart and Beethoven up through Verdi and the Alpine Symphony. Something for everyone." No, Maestro, not quite for everyone.

Composer Art Jarvinen, known as “the West-Coast totalist” (poor guy, he never got to come to any of the parties), writes to remind me, in detailing qualities of totalist music, that there was a characteristic totalist instrumentation as well as rhythmic style:

Composer Art Jarvinen, known as “the West-Coast totalist” (poor guy, he never got to come to any of the parties), writes to remind me, in detailing qualities of totalist music, that there was a characteristic totalist instrumentation as well as rhythmic style:

For totalist music to really work requires an edge. A lot of totalist composers have guitar or saxophone or electric keyboards (Rhodes, Hammond, Mini-Moog), or drum set, as their main instrument. I wrote for chromatic harmonica and baritone sax. I don't want to hear a totalist piece for the Berlin Philharmonic, I want to hear Icebreaker, or the Berlin Phil-Harmonica Band! That's why the Bang on a Can All Stars have an electric guitar. And Evan Ziporyn plays bass clarinet as if it were a Stratocaster! My totalist rhythmic/contrapuntal ideas and techniques might work with a string quartet, more or less. But my "totalist" pieces, if we are to call them that, work best with more vernacular (less standard/classical) instrumental combinations, that provide a certain edge not available in the standard instrumental groupings that are all about blend and balance. Balance? That's why we have a guy at the mixing board!

When we recorded [Art’s piece] Clean Your Gun, I could hardly get the engineer to do what I wanted, which was, run the harmonica, cello, violin, and baritone sax through guitar amps, crank 'em up, and mic the amps. He didn't want to do it, even though I was paying him to. I had to tell him, it's my piece, we're going to take a bit of paint off the walls, and you just get it on tape! There is a clarity in amplification, vernacular instrumentation, and players who play like rock musicians - i.e. with a soloistic attitude and stage presence - that I would consider a vital and indispensable factor in the development and successful delivery of the totalist style. I would probably not have written any of my totalist pieces if I didn't have access to the instrumental doublings of the E.A.R. Unit. They just wouldn't sound right.

It’s true, there was generally a kind of mixed, all-or-partly amplified ensemble sound that made those pieces come off. Just as Nancarrow had to harden his piano hammers to keep his counterpoint masses from softening into mush, totalist music needed amplification and instruments with percussive attacks to bring off the gear-shifting tempo contrasts.

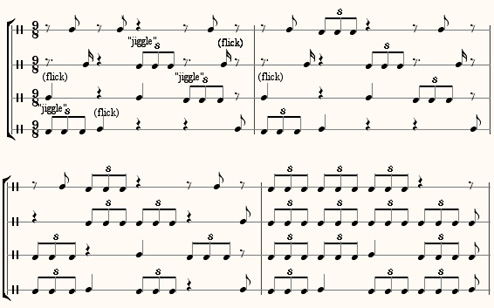

Although I might also mention that one of Art’s most rhythmically inventive works, The Paces of Yu (1990), was scored for solo berimbau (a simple Brazilian stringed instrument) accompanied by pencil sharpeners, window shutters, plucked wooden rulers, wooden boxes, mousetraps, and fishing reels. Here’s a small excerpt from the score, showing a section for flicked and jiggled window shutters. It employs a fairly common totalist or metametric rhythm, triplets in odd-numbered meters, so that downbeats contradict the momentum set up by the triplets, and also a gradual rhythmic process, showing the inheritance from minimalism:

And here’s a recording, courtesy of the California Ear Unit and O.O. Discs. (Warning, the opening is very soft for a few minutes.) It's hardly a sonically typical totalist example, but a suitably whacky bit of pure Jarvinen.

In my extensive post on Metametric music (you know, The Style Formerly Known as Totalism, c’mon, man, get with the program) I mentioned that I could never figure out how the California Ear Unit performed the three meters at once of Art Jarvinen’s Murphy-Nights. To save you from having to look, the piece starts off with an 8/4 ostinato (32 16th-notes) in the electric keyboard against a 33/16 ostinato in the electric bass - on top of which the rest of the ensemble enters in changing meters, starting in 6/4. (You can hear the effect here.) I wish I could show you the actual score: in its postminimalist way it's as scary as any early Stockhausen outside of Gruppen. I’ve known Art for years and could always have asked him how they did it, but sometimes when I’m amazed by something I enjoy not knowing the secret, and just letting my imagination run wild. Well, Art decided to dispel my imaginings, and I provide his explanation - which will ring familiar, I think, to every composer/performer who has performed in his or her own chamber music. The trick, he says, was

rehearsal, mainly. But some other factors played in.

First of all, it's just not that hard for the melody instruments to lock into the keyboard, which is in straight 8 - might as well be four-four. The bass is the one that has to be on his toes, and that was me. When I came up with the idea, I test drove it at home, playing bass over a tape of the keyboard part. No problem. Knowing I could hang with it, the rest of the group just had to follow the keyboard, and trust me to be with them at the next big downbeat. We played the piece live exactly 14 times, and no, we didn't always get it right, but we did most of the time. For the recording we put down bass and keyboard together first. That was the only take (he said somewhat proudly, but not smugly). It was such a treat to work every day with such great players.

Almost the whole group had a couple of advantages over most conventional players such as orchestra section players. We had played a LOT of Reich, as well as Michael Gordon, Andriessen, etc. We cut our teeth on music made from these sorts of schemes. And of extreme importance I would add, is that most of us played in rock/jazz/pop bands, and understood groove as a collective thing, not just accuracy within one's own part. The one time we had some difficulty getting the piece to work was when we broke in a new keyboardist. Fabulous player, but zero pop music experience. Even played "accurately" the groove wasn't happening. So we had a sectional with just bass and keyboard, with clarinetist Jim Rohrig coaching the keyboardist on feel, not counting. It all came together again pretty quickly after that.

Back when I used to perform in my own ensemble pieces, I’d write rhythms in my own part that I wouldn’t have dared put anyone else through, and also left parts blank to fill in in performance. Art also adds commentary to my post on Lucky Mosko’s music:

You definitely zeroed in on a couple of major issues, things he was consciously trying to do, such as sabotage the listener's sense of temporal placement. His succession of "nows" forms a coherent continuum - of sorts - but it's not a "classical/logical" formal argument he makes. I always thought of all of Lucky's pieces as "middles" of a much larger, eternal, piece, that we are given samples of now and then. None of his pieces really start or end. They just happen.

While I’m at it, I was about to say (before Samuel Vriezen anticipated me) that I could imagine making a distinction between metametric music and totalism. Part of the idea of totalism, beyond the rhythmic issues, was that it brought together elements from rock, jazz, and world musics, and also appealed both to pop music fans and postclassical fans. The term metametric focuses in on just the rhythmic angle, and (since coined by a Dutch composer in response to an American style) could indicate a broader realm of music, defined more technically and less by style and milieu. Don’t goad me on this, you don’t want to know how anal I can get when it comes to defining musical terminology.

I always feel bad making a big deal out of a composer right after he dies. If I knew in advance, I’d make a big deal out of each one just before he died. (Don’t any of you write and tell me you’re not feeling well. I’ll need a note from a doctor.) It’s always made me happy that, a few months before he died, I called Morton Feldman, in print, the Greatest Living Composer, and he saw it. But even had I known in advance that Lucky Mosko (1947-2005) was going to die at 58, who knew he was that old already?

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny - or gnarly, in the parlance of our time - but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny - or gnarly, in the parlance of our time - but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.

While Mosko’s style is distinctive, each individual piece is difficult to characterize on just a few hearings. My favorite so far is Psychotropes of 1993, which, according to Josef Woodard’s liner notes, is structured as a series of 22 palindromes. If so, they’re well disguised; I can find fleeting phrases coming back in retrograde, but I have a devil of a time catching points at which things turn backwards. Mosko’s most famous pieces, by which I mean I had already heard of them, were a series of Indigenous Musics, which he wrote because he was the only composer living in Green Valley, California, and felt he had a right to determine what the area’s indigenous style was. He seems to have had a sense of humor as cute as his father’s, who nicknamed him Lucky because he was so lucky to have such a father, and it manifests in the music.

In any case, I’ve put up about an hour of Mosko’s music on Postclassic Radio, including the 1997 String Quartet that someone sent me an mp3 of. Let the critical absorption of his music begin, or if it has already begun, expand.

A helpful reader with a fake e-mail address has written in to accuse me of "writing myself into history" by including myself in the discussion of totalist music in my previous post. Lest there be any further confusion: This is my own personal blog, which I am not paid to write. While I do not knowingly publish falsehoods here, I may sometimes cast myself in a favorable light. The blog is not intended to replace scholarly musical reference works. If you would like to read scholarly accounts of the totalist movement that make no reference to me, I recommend the ones I have written in Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, in my book American Music in the 20th Century, and in the final chapter of Wiley Hitchcock's Music in the United States. These are all intended to be objective and historically factual. Remember, kids, don't rely on blogs as research for your homework.

Oh, and while I'm at it, be warned: Sometimes on Postclassic Radio, I play my own music. I wouldn't want anyone to be surprised and feel shystered.

Meanwhile, Samuel Vriezen, who names a couple of Dutch composers who work with totalist rhythmic ideas, himself included - I hope our anonymous friend doesn't mind Sam mentioning himself - has come up with an alternative name for the movement: Metametrics! Metametric music, metametric music.... I like it! Sounds steely and machine-cut.

We call Monet’s Rouen Cathedral an Impressionist painting. Imagine a skeptic challenging this statement. “Let us put the painting under a microscope,” he says, “analyze it, and determine once and for all whether it is actually Impressionist.” Can we go along with his experiment and prove him wrong? No; more appropriate to say, paraphrasing Wittgenstein, that this skeptic doesn’t understand the rules of the word game we’re playing.

I don’t know whether it’s symptomatic of the decline of culture, but it seems that most people these days no longer understand the word game of artistic -isms and movements. A term denoting inclusion in an artistic movement is a kind of performative utterance masquerading as a descriptive one. A performative utterance, as J.L. Austin defined it, is one that is itself an act, one that changes the truth value of something by being spoken, like “I pronounce you man and wife,” or “I accept your offer.” If someone with the authority to make this statement says, in appropriate circumstances, “I pronounce you man and wife,” you can’t contradict him by saying, “That’s not true, they aren’t married.” The fact that he says it is what makes it true. Of course nothing in physical reality is changed by the utterance. The statement is a command that we should consider something to be changed.

Likewise, using an artistic term is an act of political demarkation; it only pretends to be a descriptive, and that pretense is its power. When critic Louis Leroy, in the April 25, 1874, issue of Le Charivari magazine, dismissed Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Renoir, and others as “Impressionnistes,” he was not describing them, as if he had said they were “tall,” or “Catholic,” or “wearers of berets.” The word “Impressionist” did not yet exist; the moment before he wrote it, it didn’t mean anything. His intent was to marginalize those painters, by insinuating that they had attached themselves to some deficient and trivial artistic principle (snidely inferrable from the indistinct word “impression”). By coining an adjective that had the appearance of objectivity, Leroy was performing the act of commanding the reader to regard those artists as mistaken and insgnificant.

The artists, however, as often happens, grabbed on to the word and subverted its meaning. They called themselves “Impressionists” in their next group show - not because it was an adjective with specific denotations that accurately depicted them, but as an act of self defense. By calling themselves Impressionists, they were telling the public, “Do not regard us as painters who have tried to master the conventions of realism and failed, but as painters who are working on something new, who have collectively perceived that there could be a different approach to visual phenomena.” By calling themselves Impressionists, they protected themselves from what they considered false criticisms, charges of deficiency based on inapplicable criteria. Years later, once those criticisms ceased to be common, they abandoned the term and went back to calling themselves merely painters. But the term itself has lasted in history.

Of course, our skeptic could have said, “There is no such thing as an Impressionist painting, there are only paintings.” In a certain trivial sense this is true. But all it really says is, “I refuse to participate in your culture of word games.” Today everyone understands that there is nothing metaphysical about the word “Impressionist.” It is simply, as defined by its historical usage, a part of cultural literacy.

And so it is with all historical terms which purport to isolate similarities among bodies of art works. Minimalism, coined for music by Michael Nyman in 1968 (these terms never just happen, they always start with an individual), means “Do not criticize this music for having a slower rate of change than you expect based on your experience of other types of music.” If Phil Glass doesn’t want to be called a minimalist, then he doesn’t want to be protected from such criticism, and doesn’t want to be seen as agreeing that his music needs any special apology. That refusal is quite within the rules of the word game. But to find the word “minimalism” contentless, to assert that there is some mismatch between the word’s chimerical “intrinsic meaning” and Music in Fifths, is merely to betray ignorance of cultural norms. “You haven’t been reading the papers.” Had Nyman christened the movement “Herbertism” instead of “minimalism,” little would have changed. The happenstance that there might be anything minimal about minimalist music is little more than a convenience, a mnemonic device. What is “Fluxus” about Fluxus art? What was “dada” about Dada? Someone coined the word, and we know what it means by how it was applied.

For that matter, what is “jazz” about jazz? Like Glass with minimalism, many Black musicians now reject the term “jazz,” saying instead “jazz music” or “the music referred to as jazz,” because they no longer want the stigma of seeming to need a special term to protect their music from false criticism. Easy enough to say now; but how would we tell the history of that great art form if, from the beginning, musicians had objected that the word had no validity? The Black musicians understand the word game: now that the music is out of danger, the term seems limiting. Still, it’s difficult to imagine how we’d function culturally without it.

Some terms, like minimalism and jazz, are positive, connoting a new technique or perception to which artists are drawn. Others are negative, open-ended, communicating little more specific than “get off my back.” The social mores of concertgoing are a cement keeping in place a whole host of listening expectations, from which composers periodically have to forge linguistic crowbars to free themselves. “Experimental music” was a euphemism coined back when the composition of music was hemmed in by a set of unspoken assumptions so obligatory that today we can hardly remember what they were. “Experimental music” meant, “I’m going to step outside those assumptions and try something else, don’t give me crap because I’m not doing what you expect.” A lot of composers, notably Robert Ashley and recently David Toub at Sequenza 21, have objected to the connotations of the word “experimental.” Many others have used the word while admitting that there’s nothing experimental about experimental music - just as one of the “New Complexity” composers once candidly admitted in Perspectives that there was no difference between the New Complexity and the Old. “Sound art” is an interesting and still-current subgenre, an island off the coast of music, and a refuge for people devoid of nostalgia for Mozart or even the piano, who don’t want their listeners reminded in any way of the world in which tuxedoed conductors shake hands with concertmasters.

”Downtown” is a term of self-defense: “don’t criticize me for not notating my music in detail and having the same types of formal contrast and information rate as European classical music, I’m not trying to do that.” Accordingly, “Uptown” was coined to relativize the dominant culture. Before “Downtown” appeared, “Uptown” didn’t exist as such, and was merely mainstream contemporary music. By assigning it a back-formation, Downtowners were able to make it appear contingent, as arbitrary in its assumptions as any other music scene - which was not only a marketing ploy, but, in fact, a valid insight. In a positive sense, “Downtown” also has the additional advantage of referring to a specific group of people at a time and place, so that we can use it to refer to musicians who performed at Roulette and the Kitchen and Experimental Intermedia in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, with no ambiguity whatever. If you performed at New Music New York in 1979, you’re a Downtowner by definition, no matter how many 12-tone string quartets you’ve written since.

Unlike Impressionism, “Totalism” was not coined by a critic, but by composers in self-defense. In New York circa 1990 there was a group of composers in their 30s who were really into rhythmic complexity and tempo structures, using 4, or 7, or 11 tempos at the same time, looping isorhythms of different lengths against each other, setting up beat-complexities that had never been heard before. Because it was static or highly limited in its use of harmony, newspaper critics, year after year, especially at the New York Times, kept calling this music minimalist, with the clear implication that minimalism had been a 1970s movement, and so this was nothing new. It was incredibly ignorant, tin-eared, dismissive, and unfair. It was driving us nuts. Someone coined the word “totalism.” Ed Rothstein wrote an article about it in the Times. I wrote another in the Voice. It was like snuffing out a candle. References to minimalism ceased. As far as I can vouch personally, it was the most successful -ism-coinage in the history of music. Faster than “impressionism,” faster than “minimalism,” faster than “Fluxus,” it put an end to the criticism overnight. It forced a perception, and then an acknowledgement, that we were doing something different. “Marketing,” you may call it. “Long overdue perception of the truth,” I call it. Most people can’t see the truth until you package it for them.