Recently in main Category

During the semester I rain forth repertoire on my students, and sometimes when I get a free moment I just obsessively need to hear something I don't already know. A Christmas DVD of Cavalli's Calisto, one of my favorite operas, put me in an early Baroque mood, so I digitized all my Cavalli and Carissimi and Cesti vinyl, and remembered that I had always wanted to be more familiar with Biber, so I discovered his two requiems, which are supremely beautiful, especially the F minor. Then I saw a reference to Nicolas Medtner, literally just his name, and suddenly realized that I had never satisfied my curiosity about the Medtner piano sonatas. They have a cult following, and since I've always hoped my music would acquire a cult following, some band of intrepid enthusiasts to run around claiming that it's not as bad as people think, I'm always on the lookout for models in that respect. So IMSLP.org has all the Medtner Sonata scores, and I could listen to them through the Naxos web site that Bard subscribes to, and I approached them the Scorpionic way I approach everything: I listened to all 14 of them back-to-back.

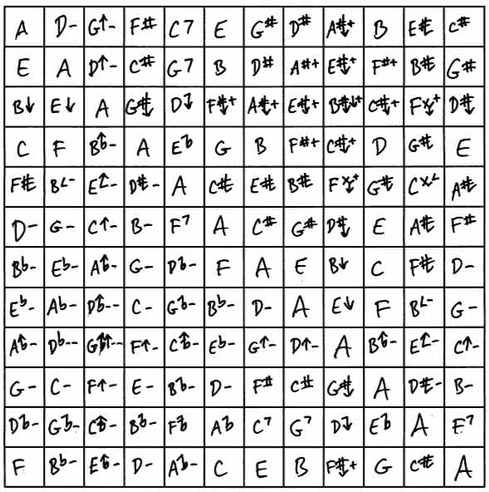

And I love them. I'm a sucker for meandering chromatic piano music anyway. Sometimes I think that as the son of a piano teacher I just find the sound of the instrument comforting, it almost doesn't matter what you play on it. But I've always considered the Scriabin sonatas a little formally timid, and Medtner leaps in where Scriabin fears to tread. His textural details are often quite original, and in his "Night Wind" Sonata Op. 25/2 he has an entire movement in a natural-sounding 15/8 meter, cleverly inflected with hemiolas:

It's great stuff, and I am now officially a card-carrying Medtner cultist. He may suddenly be my favorite Russian ever besides Stravinsky, and I hardly think of Stravinsky as Russian.

At the same time, I can see why Medtner has never gone mainstream, and never will. Except for the rather immature Op. 5, stylistically, those sonatas are much the same. Supposing I want to hear (or play) Medtner, which sonata do I choose? Hearing them all in four and a half hours, they could just as well have been one piece; which movement went with which sonata didn't make much audible difference (and I've given several of them repeat listenings, with and without scores, and played through movements). There are lots of wonderful harmonic sequences, broken by reappearances of dotted-rhythm motifs. Some are stormier than others, some are multi-movement, some long, some short, but it's a 280-minute mass of solid Medtner. The music doesn't breathe much, and no real adagio ever appears. He had a tremendously sophisticated language in which he could sit down any time he wanted and write more Medtner. But with a few exceptions (mostly the early Op. 11 trio of sonatas and the late Sonata-Idylle, I think, and the "Night Wind" has some distinctive material), he didn't have "an idea" for each sonata which differentiated it sharply from the last sonata. Like Bruckner and his symphonies, Medtner pretty much had one sonata in him and wrote it 14 times, and I don't mean to disparage either composer in the least, for I yield to no one in my Bruckner worship. But it does mean, I think, that the listener's attention is drawn more toward Medtner as a style than toward, say, the Sonata Manicciosa as a discrete piece.

Let's go back to this blog's default composer Feldman for a moment. Feldman had it all. He had an instantly recognizable style. At the same time, think about how distinct three of his orchestra pieces are from each other: Turfan Fragments, Coptic Light, For Samuel Beckett. No one who knows those pieces would confuse them on a drop-the-needle test. (Kids, dropping the phonograph needle on a record was what we used to do with vinyl, to enliven our cave parties.) Within his well-defined idiom, Feldman could create a striking image for each piece that set it apart from the rest of his output. Or to take a competitor with whom Medtner would have been all too familiar, Beethoven's Sonatas do not dissolve into Beethoven-language. I could be in a mood to hear Op. 111, or Op. 90, in which Op. 53 or Op. 57 would just not fill the bill. It's not true of every Beethoven's sonata, but the best of them each define a small (or large) world.

It is a trap that some composers fall into (and there are so many of them, aren't there?, traps, I mean) that they can develop a language and then sit around writing pieces in that language. A piece is not simply nine yards of a given composer's language snipped off from the rest - it's a thing with its own bounds and unity and personality. Years ago Boulez made some statement about having "perfected his language," and I wrote an article with the sub-headline, "Pierre Boulez perfects his language - but does he have anything to say?" Music and language are analogous in various respects, and the fallacy that music is only a language is so seductive that it sucks certain people in, letting them forget the fact that much of what we remember and most savor in music are specific sonic images. The composer may have a big impact - but his or her pieces may be individually forgettable.

And, from whatever congenital impulse that's hardwired into my amygdala, that's a trap I am more averse to than some of the others. I am driven to make each piece as individual as possible. I hate repeating myself. I have a big bag of quirks, but I don't think I possess "a language." Every major piece I start seems to require a new way of composing from me, which is why I often spin my wheels for awhile when I first get started. I probably overemphasize with my students that they think about what "the idea of the piece" is. It could be called a more "objective" kind of composing, because the entire emphasis is on the object, and I am always willing to abnegate any usual composing tendencies I think of as mine to achieve what the piece needs. And perhaps, avoiding that Scylla, I fall prey to the Charybdis of not having an individual enough composer profile.

There are historic composers, some among my favorites, like me in this respect. Nancarrow rarely repeated anything. A kind of "Nancarrow style" is imposed on our perception of him by the fact that 51 of his pieces were for the same peculiar instrument, but in my book on him I list 26 good ideas that he used once and never touched again. He could be tonal or atonal, jazzy or abstract, chaotic or elegant, and any permutation of those. Or to take a more directly apposite contrast to Medtner, Ferruccio Busoni is one of the most piece-oriented composers ever. If you've heard of him at all, you know he has a big romantic piano concerto, and some sonatinas, but the concerto is in a complete different idiom from the sonatinas, and the sonatinas hardly match well enough to constitute a set (one atonal, one Bach-like, one based on Carmen for gosh sake), and the string quartets and operas are something else altogether. Busoni is one of my very favorite composers, and even I can't make the Romanto-Moderno-Neoclasso jigsaw puzzle of his output fit into a picture. Each piece has an impact, but Busoni himself has a fuzzy reputation.

Of course, the preferable thing would to be like Beethoven or Feldman or Stravinsky, and write memorable pieces within your own distinctive style. But it doesn't seem that we get to choose where we fall along this continuum, whether it is decided for us at birth by the structure of our neural system or imposed upon us from without by the opportunities we're given. Still, who says that that coveted middle position will make you everyone's favorite composer? Some of us are drawn to artists whose strengths are less obvious. If I'm offered the position as my generation's Busoni, I'll leap at the chance. And I suppose what I'm saying is that there are advantages on both sides. I can listen to Steve Reich and say, "Boy, I wish my music had that clear a profile"; but I can also listen to Medtner - and love every note of it - and still say, "Boy, I'm glad my pieces don't all blend together."

I want to draw attention to Allan Kozinn's thinkpiece about the vagaries of new-music performance in yesterday's Times (tried to post then, got caught in a holding pattern involving site changes), which is pitch-perfect in talking about why, how, and with what expectations performers should undertake the performance of newly composed music. I would add one thing. I would urge new-music performers to look for composers to commission outside the usual roster of composers on the regular chamber-music or orchestra circuit. Many of the best composers are better at composing than they are at networking, and are devoted enough to get their music out that they'll do it by themselves if that's what they're reduced to. That means they may work in some electronic or self-produced idiom which you mistakenly think is all they're interested in, or talented for. You may think they're not really chamber music composers, or couldn't write for piano trio, or something, and you might often be entirely wrong. For instance, no classical chamber group would commission Glenn Branca, right?, since he only writes for electric guitar ensembles - except that Glenn's string quartet is one of his best works, and one of the most beautiful essays in that genre of the last 25 years. (No recording of it exists that I know of, unfortunately, but I once heard it live and reviewed it.) And Carl Stone is an electronic composer, he wouldn't know how to write an acoustic piece - except that the piano pieces Sarah Cahill has commissioned from him are absolutely charming.

Kozinn is exactly right that a new piece needs to get played publicly and played well, and considered for awhile, before we can decide whether it's a keeper. Similarly, composers who show brilliant imagination in one medium need opportunities to branch out into others, and shouldn't be bypassed based on some superficial canard about "proven track record" in a given medium. You might occasionally draw a clunker, just as you can with any Pulitzer prize winner, and it's a risk you have to take. But a composer who's spent his life in solo performance or electronics because it was the only route available might turn out to have a couple of gorgeous string quartets inside him (Ingram Marshall is a classic example).

In an unrelated bit of news, I note that Postclassic remains number 6 on the ranking of classical music blogs. I've been passed up by Nico Muhly as the top single-composer blog. Frankly, I've done so much to reduce and alienate my readership that I'm astonished to still be in the running at all. I rather think of this blog as a book I wrote awhile back that I'm still adding the occasional footnote to - that, and also I've been incredibly overcommitted lately, and am turning down writing jobs left and right. But despite all my most cantankerous efforts, there I remain. Strange indeed.

I've finally gotten around to buying and reading Howard Pollack's book on John Alden Carpenter, which I'd fondled in bookstores for years. It's a succinct, engaging, curiosity-satisfying piece of scholarship. Curiously heavy on the critical reception of Carpenter - so much so, in fact, that he spends considerable space on a 1986 review I wrote for Fanfare magazine of Carpenter's piano music. Carpenter is a composer whose tragedy was to watch his reputation soar and then to plummet in later life, to the point of becoming almost a figure of fun to younger composers.

Yet Carpenter remains a famous name. When I was young, he was one of the first "modern" composers I heard of. And what pieces did I read about? Skyscrapers and Krazy Kat. Why? Because Carpenter lived in Chicago in the jazzy 1920s. He was part of the age of skyscrapers and newspaper comics and heavy machinery, and his music betokened the point at which exploding urbanization still seemed sexy. Skyscrapers and Krazy Kat fit his narrative. He also wrote a tone poem called Sea Drift that Pollack and others consider a better piece. But Sea Drift? Number one, Chicago is a long way from any sea. Two, that's a Walt Whitman reference, and Whitman was an East-Coaster, and besides, Sea Drift is Vaughan Williams and Delius territory, part of the maudlin British transatlantic experience, not material for the jazzy and urbane Carpenter, wealthy heir to a manufacturing fortune. Sea Drift may be a better-written piece than Krazy Kat (not so I'm convinced of that, actually), but it had never entered my consciousness, even though I've had the Abany Symphony recording since it was on vinyl. It didn't fit my narrative of Carpenter. The fact that he wrote a sentimental tone poem on Whitman is a cognitive dissonance with my image of him, magnum opus notwithstanding.

(For the record, and before I get to my main point, going deeper into Carpenters's music has convinced me that he is rather woefully underrecognized. He never should have written that damn Perambulator piece, it trivialized his reputation. It's true that even his symphonies have a kind of unfocused, balletic quality that sounds like film music today, but the music is always graceful and "debonair" - to repeat the aptest term it habitually elicited. And fairly often, as particularly in his 1927 String Quartet, it achieves an enchanting vigor and rhythmic surprise. Look up that string quartet, it's a forgotten classic.)

To be absorbed into the public dialogue requires a narrative. To not project a narrative is to have no career at all. Only a few dozen musicians, or if you're lucky a few hundred, will ever take a close enough look to see what you've actually accomplished. The rest of the musical public will inevitably receive a caricature of you, because that's all they have time or attention or insight for. That's the veil of Maya, of illusion, the conventional wisdom that we can look down our nose at but whose influence we can never escape. The public can take in Carpenter = Krazy Kat because it makes sense, but Krazy Kat plus Sea Drift is too complex, too nuanced, for even the peripheral imagination of a scholar like myself, and only now have I gotten around to more than a peripheral look. I ignored Sea Drift as an almost painful reality, because it took some effort to factor into the image of a composer I didn't yet have the incentive to focus on.

Common sense and self-interest would dictate that composers would play to their narrative, but most of us shrink from it in disdain. Take me. I've made a big deal about microtonality, and I find myself almost universally described as a microtonal composer, even though some 2/3 to 3/4 of my output so far is in the good old 12-tone scale. Custer and Sitting Bull is probably my best-known piece, or the piece with which I'm most associated. And for good reason - it combines microtonality with my Texas roots and my interest in American Indian music. It fuses well with my bull-in-a-china-shop personality, my 6'2" stature, and my southern accent. Were I a short, Jewish New Yorker, this piece would never have gotten off the ground. Had I been attentive to my narrative, I would have followed it up with, say, a microtonal opera about Jesse James, or a song cycle on the letters of Calamity Jane (which Ben Johnston actually beat me to). I could have become the "microtonal wild-west-history composer." Instead, I wrote a chamber quartet called Kierkegaard, Walking, with 12 pitches to the octave. I think it's one of my best works. But what was I, a Texan transplanted to New York, doing having a fascination with Kierkegaard? How much of my life has taken place in Denmark? Four days. Kierkegaard, Walking may be my Sea Drift, a piece so incongruent with my image, my narrative, that no one wants to notice it. In fact, my personal image includes an affection for 19th-century writers, including Emerson, Kierkegaard, Thoreau, Jones Very, and even Custer (as memoirist) and Sitting Bull (as orator). But that's both a little complex for a narrative and not terribly distinctive in terms of distinguishing me from other composers.

We can all name a few composers who do seem to assiduously sculpt their narrative. I recently had a chance to examine the scores of Steve Reich's Sextet and Double Sextet, and nearly slapped my forehead when I saw how similar, how identical in notation and gesture, they are to Six Pianos, Music for 18 Musicians, and all those much older other pieces. I had the presumably common thought that I could write my own Steve Reich piece at this point, and hardly needed Reich to do it for me. He's been unbendingly faithful to his brand. He sells a ton of records because he's predictable - or the kinder word would be reliable.

The vast majority of us, I think, resist this. We don't want to be "pigeonholed" (an overused word, and what does it mean?). We want to show off our range, our versatility. I wrote once that Bill Duckworth was the Schumann-like modern master of multi-movement form, and his next piece was Blue Rhythm, in one extended movement. I noticed publicly that Joan Tower uses the motive of a minor third expanding to a major third in virtually every piece, and in her next work, the Third Quartet, that figure was conspicuously absent. Most of us are embarrassed at being caught repeating ourselves, even in our virtues. We want to prove we can master both collages and drone pieces, adagios and scherzos, tonality and atonality. Or else we simply get bored replicating earlier achievements, and having done one kind of thing well, now want to succeed at another. Or we fancy ourselves above the usual forces of history, fancy that the inherent power of our art will break through the veil of illusion and move listeners in no matter what genre, in pursuit of no matter what subject matter. This might have been more likely 200 years ago when the competition was less voluminous. Yet even so, there are Beethoven works, like his early choral music and those Irish folk songs he was so painfully proud of, that we can't bear to look in the face. Even Beethoven has his Sea Drifts.

To so reflexively resist the call of the narrative seems, actually, counter-productive in a career sense, almost self-destructive. Poor Carpenter, had he not wanted to slide out of the scene, should doubtless have followed up Krazy Kat and Skyscrapers with a Machine Symphony, a ballet called Streetcar, a tone poem about Wall Street. Having cornered a certain market, he should have churned out more of what the public believed he could do best. Instead, he wanted to prove his soulful, Brahmsian earnestness with a respectable Piano Quintet and a Violin Concerto (which, amazingly, seems never to have been recorded, and Pollack makes it sound intriguing). As a result he slid into semi-oblivion. We composers, we are all John Alden Carpenters, and, however much prized by specialists, will enter public consciousness only, if at all, through the narrow tunnel of the available narratives, which are only partly susceptible to our own shaping. And so, with the loftiest intentions, we embrace obscurity rather than be so confined and only incompletely understood. It's peculiar.

And with that thought, merry Christmas.

Sites To See

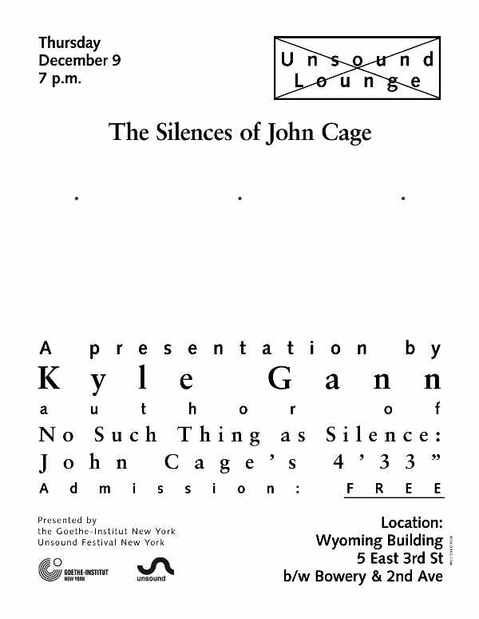

American Mavericks - the Minnesota Public radio program about American music (scripted by Kyle Gann with Tom Voegeli)

Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar - a cornucopia of music, interviews, information by, with, and on hundreds of intriguing composers who are not the Usual Suspects

Iridian Radio - an intelligently mellow new-music station

New Music Box - the premiere site for keeping up with what American composers are doing and thinking

The Rest Is Noise - The fine blog of critic Alex Ross

William Duckworth's Cathedral - the first interactive web composition and home page of a great postminimalist composer

Mikel Rouse's Home Page - the greatest opera composer of my generation

Eve Beglarian's Home Page - great Downtown composer

Just Intonation Network - a meeting place for people interested in alternative tunings

Erling Wold's Web Site - a fine San Francisco composer of deceptively simple-seeming music, and a model web site

The Dane Rudhyar Archive - the complete site for the music, poetry, painting, and ideas of a greatly underrated composer who became America's greatest astrologer

Utopian Turtletop, John Shaw's thoughtful blog about new music and other issues

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary