PostClassic: July 2009 Archives

If nature is not enthusiastic about explanation, why should Tschaikowsky be?

- Ives, Essays Before a Sonata

I suppose I shouldn't be so enthusiastic about explanation. It's a reaction to frustrations of my youth, in which there was so much information I couldn't get access to: all those years of knowing the names La Monte Young and Charlemagne Palestine, and not being able to hear their music, all those hints of how Le marteau was written in Boulez's On Music Today, but the final key withheld. Composers like Boulez build up a mystique by keeping their methods secret, and I suppose it's a smart strategy, but I swore early on I would never do it, even to my own detriment. I may only be flattering myself in so imagining, but there might be a young composer out there curious to figure out how I did what I did in my new piece Solitaire, and I'd rather empower him or her to do something similar than pose as some unapproachable magus.

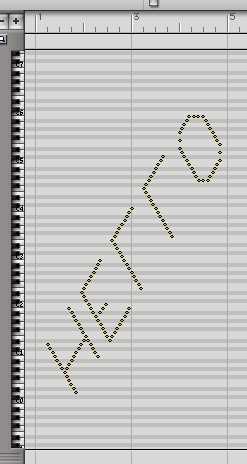

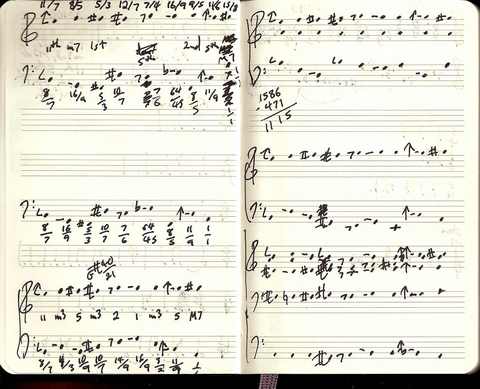

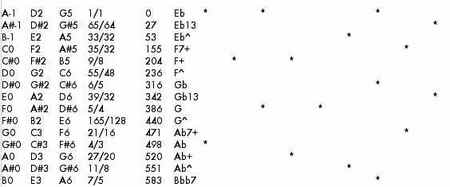

Solitaire (14:05 in duration) is a piece in which I extremely limited my materials, and vowed not to deviate beyond what happens in the first few measures. My sonic idea was a continuum between perfectly familiar chord progressions and perfectly strange ones. So I started with ii, IV, V, and vi chords in the key of E-flat. (I never use the tonic chord, of course.) I added a major seventh chord on flat III, because it filled out the scale nicely. The other chords are seventh or ninth chords on the 7th, 11th, and 13th harmonics and the 7th subharmonic. For maximum short-circuiting of aural understanding, I mostly go back and forth between the Roman-numeral chords and those based on harmonics, but I occasionally relax into a normal IV-V-vi progression which, I hope, takes the ear as much by surprise as a bizarre outburst would in a more conventional piece. The 29-note scale, for people who can read musical ratios, is as follows:

1/1, 65/64, 33/32, 15/14, 35/32, 10/9, 9/8, 8/7, 6/5, 39/32, 5/4, 9/7, 21/16, 4/3, 11/8, 10/7, 35/24, 3/2, 99/64, 13/8, 5/3, 27/16, 12/7, 7/4, 9/5, 117/64, 15/8, 40/21, 63/32

In dark night live those for whom

The world without alone is real; in night

Darker still, for whom the world within

Alone is real. The first leads to a life

Of action, the second to a life of meditation.

But those who combine action with meditation

Cross the sea of death through action

And enter into immortality

Through the practice of meditation.

So we have heard from the wise.

I've long wanted to blog about "Age of Anxiety." Not a perfect piece by any means, and the sentimental ending degrades into ersatz Copland, but the first half is both scintillatingly clever and moving, with a theme and variations that exemplifies Schoenberg's concept of "developing variations" better than any other piece I know, especially by Schoenberg. In its day it was dismissed by musical intellectuals on account of its stylistic heterogeneity: its splashes of Brahmsian romanticism and brainy jazz in an otherwise diatonically modernist idiom. For years I listened to it in private, score in hand, as a guilty pleasure. But then in the '80s that kind of pastiche became the orchestral establishment's new hip trend, and "Age of Anxiety" is way overdue its rehibilitation. After the concert I talked to many musicians, and found only one, composer and BSO program annotator Robert Kirzinger, who shared my enthusiasm for the Harris. I guess my relation to that piece is atypical for my generation (what else is new?), but I discovered it at 13, and it became my most fervently envied formal model. There are some low-profile themes in that piece that run through it unobtrusively, and score study helps you understand why it sounds so ineffably unified.

As I've said before, I leaped into Cage with both feet at 15, but before that I had already been indelibly imprinted by Gershwin, Ives, Copland, Bernstein, and Schuman, so while the Downtown repertoire left a thick veneer, the undercoating was pure American symphony. So sue me.

I've been thinking, all this year, about teaching a course on the American Symphony, and perhaps even writing a book. Last fall a friend bought me a score to Virgil Thomson's Symphony on a Hymn Tune, one of my favorite pieces in the entire world. About that time I was also writing a review of Joseph Polisi's new biography of William Schuman for Symphony magazine, which (the review) got bumped twice, but came out a month or so ago. The Thomson score made me realize that I could probably start finding scores I wanted on the internet, rather than buying merely what I happened to come across at now-defunct Patelson's in New York. So I started looking around, mostly at The Sheet Music Store, and ended up ordering the following symphonies: Harris 9, Schuman 3 and 6, Cowell 4, Piston 7, Persichetti 4, Hanson 2, and Glass "Low." I also found Thomson's Third and the St. Joan Symphony of Norman Dello Joio in a used book store in Hudson. (This was all back in October when it looked like my personal finances were going to be happily bypassed by the economic Fall of Civilization.) All of them arrived except the Hanson, which I'm still waiting for (and Hanson expert Carson Cooman tells me I should have gotten the First or Third instead). They weren't necessarily the symphonies I would have dreamed of, but they were ones I could find by composers who interest me.

And frankly, things don't look good for the class, let alone the book. More often than not, I was disappointed. Reading through a score usually changes my opinion of a piece a little for the better or worse, and most of these went through a negative reassessment. Most depressing was the Harris Ninth (1962), which is a terrific mess. It's as though Harris lost sight of everything that had been wonderful about his earlier music, all the broad themes and rhyhmic energy, and just started noodling randomly in what he considered "his style." After reading it through closely with the recording, no impression remained at all, just a morass of piquant polychords absent-mindedly distributed. Cowell's Fourth (1946) is a significantly more coherent piece, but similarly undistinguished - it could almost have been written by any mid-century minor pedant. Of course Cowell is one of my heros, but most of his symphonies were written after his unfortunate San Quentin experience, which turned him into what most people would have to consider a more conservative composer. I wished I could have found No. 16, the "Icelandic," which is a little more fun.

The one piece that didn't suffer at all was Schuman's Sixth (1948), a tough, trenchant, impressively polyphonic work that may be, as some have said it is, the peak of his output. I had always been a fan of his Third (1941), and still am, though on close inspection it struck me as a little wandering.

Persichetti's 4th (and I hate to say it with American Symphony expert Walter Simmons possibly reading) made very little impression on me after repeated hearings: expertly written, measure for measure, as he always is, but with no discernible throughline. The most disturbing score I found, though, was Piston's Seventh (1960): an absolutely joyless, dogged work, carefully crafted around unmemorable themes as in a grim determination to churn out another correct example of the genre. He proved that one didn't need 12-tone technique to suck all playfulness out of orchestral writing. A more interesting venture was the Dello Joio, which had the advantage of clearly outlined ideas. Thomson's Third, an orchestration of one of his string quartets, was also disappointingly uninspired. And while I love certain passages in Glass's "Low," it's a little watery, and even the stirring parts repeat until you start muttering, "OK, OK, I get it already."

The problem with a course or a book is that the great American symphonies, even by great American composers, are exceptions, not the rule. Symphony production swelled to emormous volume in the 1930s and '40s (I once did a survey course on symphonies and found 1946 as the climax year), and a kind of generic, upbeat symphonic style became the order of the day. Composers like Cowell and Thomson seemed to compromise most of their principles to get a monumental work out there, while obsessive craftsmen like Persichetti and Piston seemed to have no concept of epic sweep. The American symphonies I get tired of never teaching are all of Ives's; the Copland Third; the Harris Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh; The Thomson Hymn Tune; the Riegger Third; the "Age of Anxiety"; the Schuman Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth; the Rochberg Second; any interchangeable Sessions work, the Third would do nicely; and now I'd add Robert Carl's Third and Fourth. (I wouldn't be adverse to adding the Antheil "1942" and Bolcom 5; Wolpe's Symphony is one of his weakest works, though, and the Bernstein "Kaddish" is lush music wrapped in an embarrassing text.) Perhaps those are enough for a course, but the list seems a little cherry-picked, and while it would be nice to focus more on the pre-WWII search for a Great American Symphony, I'm afraid I would end up feeling too apologetic. An analysis class around Harris, Thomson, Schuman, and Bernstein sounds both peripheral to student interest and too ambitious. So I feel like the dream isn't ikely to come true in any forseeable future, but at least I can now say I heard Bernstein 2 and Harris 3 live, and drank in every note like nectar.

UPDATE: Someone remonstrated with me that great pieces of music are always exceptions, never the rule. Of course, that's a truism. But in this particular context, why is Thomson's Hymn Tune Symphony so inspired, his Third so tepid? Why is Bernstein's Second a piano concerto and his Third a weird, '60s-ish theater piece? Even Ives's symphonies are cut from diverse patterns: the first Dvorakian, the Second a playful romantic romp, the Third unconventional in form but deeply religious and originating in organ improvisations, the Fourth mystical, philosophical, and presciently modernist. Compare with the symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms, Dvorak, Bruckner, Mahler, who each possessed a fairly consistent concept of what a symphony is, developing it from work to work, so that if you like any one of those composers' symphonies, you're pretty much guaranteed to similarly appreciate at least all of its successors. In that sense, the great European symphonies are not the exceptions. Please read generously - there's often a meaning that can be teased out with a little thought, and one can't take the time to explain everything.

Draw a straight line and follow it.

As one moves around the room, the audible overtones change markedly over the distance of a few inches, dependent on where one is among the nodes of pitches reinforced by the acoustics of the room. This aspect of the WTP is almost entirely unrepresented by the recording under average circumstances; since it is determined by room acoustics and position in space, no microphone can entirely convey the variety of audible phenomena the WTP generates. Analysis of such transient effects lies outside the scope of the present paper. (Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 31 No. 1 [Winter 1993], p. 149; emphasis added)

Beethoven had to churn, to some extent, to make his message carry. He had to pull the ear, hard and in the same place and several times...

Charles Ives, Essays Before a Sonata

Roll A

Roll MM

Roll R

Romantic roll

Roll with "hello"

With some slight hesitation I post a new and rather comical work to the internet. It was supposed to be titled Triskaidekaphonia 2 because it uses the same tuning as my piece Triskaidekaphonia, but it turned out so programmatic that I couldn't leave it with such an abstract title. So it's The Aardvarks' Parade (click to listen, just over ten minutes), in honor of an animal with which I had a childhood fascination. For the first time ever I've written a microtonal piece in a scale I'd already used before, and it's the simplest one I've ever used: all the ratios of the whole numbers 1 through 13 multiplied by a fundamental, yielding 29 pitches. The form is AAAA: I was musing about a melody repeated over and over, in simple quarter-notes and 8th-notes, but so intricate in its tuning that several repetitions wouldn't be enough to make it predictable. If I Am Sitting in a Room is the conceptualist Bolero, maybe this is microtonality's Bolero. I tend to repeat things four times in my pieces: partly because it's an American Indian tradition, paying homage to the East, West, North, and South, and partly because my first college composition teacher, Joseph Wood, told me that you could only get away with repeating something three times in a piece, instantly stirring my innate rebelliousness.

With some slight hesitation I post a new and rather comical work to the internet. It was supposed to be titled Triskaidekaphonia 2 because it uses the same tuning as my piece Triskaidekaphonia, but it turned out so programmatic that I couldn't leave it with such an abstract title. So it's The Aardvarks' Parade (click to listen, just over ten minutes), in honor of an animal with which I had a childhood fascination. For the first time ever I've written a microtonal piece in a scale I'd already used before, and it's the simplest one I've ever used: all the ratios of the whole numbers 1 through 13 multiplied by a fundamental, yielding 29 pitches. The form is AAAA: I was musing about a melody repeated over and over, in simple quarter-notes and 8th-notes, but so intricate in its tuning that several repetitions wouldn't be enough to make it predictable. If I Am Sitting in a Room is the conceptualist Bolero, maybe this is microtonality's Bolero. I tend to repeat things four times in my pieces: partly because it's an American Indian tradition, paying homage to the East, West, North, and South, and partly because my first college composition teacher, Joseph Wood, told me that you could only get away with repeating something three times in a piece, instantly stirring my innate rebelliousness.Cage wrote a mesostic for Nancarrow that reads, "oNce you / sAid / wheN you thought of / musiC, / you Always / thought of youR own / neveR / Of anybody else's. / that's hoW it happens." I think I probably could have been as reclusive as Nancarrow, had not economic necessity forced me into the public life of music criticism. But I certainly am not like Nancarrow in this other respect. A life exclusively focused on my own music seems unimaginable. My musicological work feeds my composition, and vice versa. When I've been doing too much critical work and not composing, I get cranky; and when I've been composing continuously, I dry up a little, and I start to need the interaction with the music of others. It's not that I steal so many ideas from other composers, though of course I never scruple to do that. Nothing about the other people's music I'm working on went into the piece I just finished, though I do absorb inspiration from the brilliant things Ashley says, and Budd always reconfirms my love for the major seventh chord. I just need that rejuvenation from other artist's ideas, the mere presence of simpatico music I didn't write.

I seem not to be unique in this respect among my close contemporaries. Larry Polansky, a far more prolific composer than myself, has done loads of important musicological work on Ruth Crawford, Johanna Beyer, and Harry Partch, not to mention running Frog Peak Music for the publishing of other composers' music. Peter Garland, in between writing his own wonderful pieces, published the crucial Soundings journal for many years, and made available the music of many who didn't seem so obviously important at the time as they do now. Some of us need this close interaction with the music of our contemporaries. Nor does it seem like just an American thing. Schumann certainly spent a lot of his career inside other composers' heads, and seems to have enjoyed having a trunkload of Schubert's manuscripts in his apartment, from which to draw for the occasional world premiere whenever he fancied. Liszt played the piano music of every significant contemporary except Brahms (who offended him by falling asleep at the premiere of Liszt's B minor Sonata).

Part of it is what I think Henry Cowell sensed: that there's no such thing as a famous composer in a musical genre no one's heard of, and so one's personal survival depends on a rising tide raising all boats. But Morton Feldman also tells a story of an artist in the '50s who, after seeing Jackson Pollock's first astounding exhibition of drip paintings, remarked, "I'm so glad he did it. Now I don't have to." And Feldman adds, for thoughtful emphasis, "That was not an extraordinary thing to say at the time." Some of us do have this feeling that art is a collective activity, that it's not all about ourselves. I hear an exquisite piece like John Luther Adams's The Light Within, and I do think, somehow, "I'm so glad he did it, now I don't have to" - partly because I want to hear that kind of ecstatic wall-of-sound genre, and he can so it much better than I could. Mikel Rouse's music is so much more sophisticated than my intentionally naive fare, but listening to him gets me back on track. I listen to Eve Beglarian's music, and I hear things I might have been tempted to do, but she's got them covered. These aesthetically close colleagues free me up to pursue what I do best, but I somehow need to participate in their achievements by analyzing them and writing about them.

We Americans are taught to worship individuality, in art above all, but there is a strong collective aspect to creativity that many composers strenuously ignore or deny. I have no idea why I'm so attuned to it, especially being as anti-social as I am by temperament. But I do know that if anyone ever regrets that I had to write all these books and articles instead of working non-stop on my own music, they will have missed the point. It's all the same thing.

What a pleasure it was to find Robert Carl's new book about Terry Riley's In C (from Oxford) in my mailbox today (or actually, on top of it, which was poor judgment on the mailman's part, since it's rained here every day for the last month). I wrote a blurb for the back cover and shouldn't say anything more, but I'm impressed once again with the smoothness and non-academicism of Robert's writing style - I thought composers had to work for a newspaper for years to achieve that. Also with the number of people he interviewed in great detail about Riley's early career, which is stuff that I'll surely end up quoting. There are people I won't have to interview because Robert's already done it. It's about time we had a book on In C, which was my generation's Rite of Spring. My Long Night (1980), though quite opposite in atmosphere, was, formally, closely modeled on it. My only thought was, if some card-carrying musicologist had written the book, and Robert had written his Fifth Symphony instead, I would be twice as happy. Why is the musicology of new music (and not all that new at that) being left to us composers? It's a question to bring up at the minimalism conference, at which Robert will be giving a keynote address.

What a pleasure it was to find Robert Carl's new book about Terry Riley's In C (from Oxford) in my mailbox today (or actually, on top of it, which was poor judgment on the mailman's part, since it's rained here every day for the last month). I wrote a blurb for the back cover and shouldn't say anything more, but I'm impressed once again with the smoothness and non-academicism of Robert's writing style - I thought composers had to work for a newspaper for years to achieve that. Also with the number of people he interviewed in great detail about Riley's early career, which is stuff that I'll surely end up quoting. There are people I won't have to interview because Robert's already done it. It's about time we had a book on In C, which was my generation's Rite of Spring. My Long Night (1980), though quite opposite in atmosphere, was, formally, closely modeled on it. My only thought was, if some card-carrying musicologist had written the book, and Robert had written his Fifth Symphony instead, I would be twice as happy. Why is the musicology of new music (and not all that new at that) being left to us composers? It's a question to bring up at the minimalism conference, at which Robert will be giving a keynote address. Sites To See

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary