PostClassic: May 2009 Archives

Sun

Moon

Venus

Mars

Jupiter

Mercury

Saturn

Uranus

Neptune

Pluto

It's official: my next book will be on the life and works of Robert Ashley, one of my favorite composers, and one of my favorite people on the planet. It's for the University of Illinois Press's series on American composers, the first two of which are excellent books on John Cage (by David Nicholls) and Lou Harrison (by Leta Miller). I've gotten sucked into the short-book industry. I'm still grinding away on that Music After Minimalism book, which is a huge project and keeps changing shape, but it has seemed professionally expedient for me to get a few books out quickly, so I'm reluctantly letting myself get sidetracked. But what an inviting sidetrack: every time I hang out with Bob Ashley (which I've been doing since 1979) I get a buzz off of his laidback enthusiasm. Great man, great composer, vastly misunderstood, so I'll get to add a lot more new information to the world than I did in John Cage's 4'33" (coming out in the fall).

It's official: my next book will be on the life and works of Robert Ashley, one of my favorite composers, and one of my favorite people on the planet. It's for the University of Illinois Press's series on American composers, the first two of which are excellent books on John Cage (by David Nicholls) and Lou Harrison (by Leta Miller). I've gotten sucked into the short-book industry. I'm still grinding away on that Music After Minimalism book, which is a huge project and keeps changing shape, but it has seemed professionally expedient for me to get a few books out quickly, so I'm reluctantly letting myself get sidetracked. But what an inviting sidetrack: every time I hang out with Bob Ashley (which I've been doing since 1979) I get a buzz off of his laidback enthusiasm. Great man, great composer, vastly misunderstood, so I'll get to add a lot more new information to the world than I did in John Cage's 4'33" (coming out in the fall).There's a story from Tchaikovsky's last years so good that you'd think it's apocryphal, but it appeared in a 1912 Moscow newspaper, and none of the principals involved ever contradicted it. In December of 1890, Tchaikovsky's opera The Queen of Spades was premiered. He felt it was his greatest work, but he interpreted the audience reaction as cold, and, after the performance, wandered the streets of Petersburg despondently. Suddenly he heard music from his opera in the street, the first-act duet between Liza and Polina. He investigated, and found three students, who indeed had acquired a piano score before the performance and attended it, and were now enthusiastically singing through their favorite parts. Their names were Sergei Diaghilev, Alexandre Benois, and Dimitrii Filosofev, and they would become friends of Tchaikovsky for the brief remainder of his life.

Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929), of course, was to become a great choreographer and impresario, a supreme figure in the world of ballet. Alexandre Benois (1870-1960) became a painter, graphic designer, and theater designer. All three men were associated with a movement to become known as Mir Iskusstva (The World of Art), which would start its own magazine in 1899 and usher in a new, 20th-century sensibility in Russian art.

What does this have to do with The Nutcracker, that simple staple of Christmas celebrations? According to Russian cultural historian Arkadii Klimovitsky, The Nutcracker (which Tchaikovsky wrote a year later in 1891/92), was the first "opera of miniatures," and its evocation of puppetry, its underlying dark symbolism, its mixture of humans and toys, and even its imitations of 18th-century music were all inspirations behind the aesthetic of Mir Iskusstva. Without The Nutcracker, it is unlikely that Diaghilev, Benois, the dancer Nijinsky, and the composer Igor Stravinsky would have gone on to create the puppet-show ballet Petrushka, one of the seminal ballets of the modern world. Now that we in the West have more open access to Russian scholarship, Tchaikovsky appears to have more direct ties to the formation of 20th-century aesthetics than his reputation as one of the 19th century's great sentimentalists would have suggested.

Tchaikovsky's reputation has changed in other ways, too. In 1891, the same year Tchaikovsky made a tour of America, a Carnegie Hall program presented Brahms, Saint-Saens, and Tchaikovsky as the three greatest living composers. By the end of the century, rumors of Tchaikovsky's homosexuality began to circulate outside Russia, and he came to be thought of in the English-speaking world as a dark, tortured individual, one who may possibly have even committed suicide to avoid scandal and exposure. Recent attention to Tchaikovsky's letters and diaries, however, shows that while he was certainly a deeply sensitive individual, uncomfortable in all but fairly intimate social situations, his sexual orientation was not nearly the burden on him that inheritance of a Victorian moral outlook would lead one to assume.

While homosexual acts were officially illegal in 19th-century Russia, the laws were virtually never enforced, and potential scandals even among the highest nobility were simply overlooked. In 1876, however, at the age of 36, Tchaikovsky decided that his sexual decadence was a bad influence on his likewise homosexual brother Modest, and he decided to marry. Conveniently, he started receiving love letters for a former student, Antonina Miliukova, and after some courtship, they were married on July 6, 1877. The composer quickly realized that he had made a terrible mistake, and that his sexual preference was not something he could change at will. After 21 days, the marriage still unconsummated, he traveled to see his sister, and when he came home in September, he stayed only 12 more days before leaving Antonina forever. (It might correctly be inferred that Antonina had a couple of screws loose, and she indeed ended her life in a mental institution.)....

Of course, I go on to Tchaikovsky's mysterious patroness Nadezhda von Meck, and the guy died soon enough after Nutcracker that I could end by throwing in the allegation about him committing suicide by drinking cholera-contaminated water - before telling the reader that it never happened.

Another effective ploy is to throw in some criticisms of the composer, contemporaneous or current. This has the double effect of making it seem that the composer labored heroically against a lack of appreciation, as all of us do, and also takes classical music down off its pompous pedestal and makes it seem OK to criticize it. The reader can then sympathize with the composer, and is primed to find the music not as bad as people say. For instance, here's what I had fun writing about Saint-Saens, a composer I heartily loathe:

The life of Camille Saint-Saëns spans ancient and modern France. [Disappointingly conventional start, but it's a setup.] At the age of 12 he played for the "Citizen King" Louis Philippe, yet he lived to write a cantata about electricity, the first film music by an established composer, and music in praise of the aviators of World War I. Liszt pronounced him the world's greatest organist, and he astonished Wagner and Hans von Bulow by his ability to sight-read the orchestral scores of Tannhauser and Lohengrin at the piano. Thanks in part to their influence, in youth he was more famous in Germany than in France - his opera Samson et Dalila, widely considered his greatest work, was produced in 1877 in Weimar, and not performed in France until 13 years later. In old age, England and America considered him France's greatest composer long after his reputation had begun to fade in his own country.

In short, Saint-Saëns stands astride French music like a colossus, but a frail one, and everyone seems to find fault with him. He was a child prodigy who composed at six and played Mozart and Beethoven with an orchestra at ten, leading the older French musical giant Hector Berlioz to remark, "He knows everything but lacks inexperience." Unlike most Romantics - Schumann, Chopin, Wagner, Liszt - Saint-Saëns wrote best in the sturdy classical forms of sonata, symphony, and concerto, yet George Bernard Shaw dismissed his music as "graceful knick-knacks and barcarolles" (the barcarolle being a piece that imitates the songs of gondola drivers). The advent of the Impressionism of Debussy and Ravel made Saint-Saëns seem like a dinosaur at the end of his life, and he railed against Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune: "I'd soon lose my voice, if I went round witlessly bawling like a faun celebrating his afternoon." Ravel returned the compliment: "If [Saint-Saëns] had been making shell-cases during the war, it might have been better for music."

Perhaps Saint-Saëns' difficulty in playing nice with others is responsible for the steep decline in his posthumous reputation. It's difficult to decide even how French he seems: extremely so in languorous melodies like "The Swan" and his fairy-like schrezo textures, the least so in his devotion to sonata form and full-bodied contrapuntal textures. (Gounod dubbed him "the French Beethoven.") He did fit, however, into a long and illustrious tradition of French organist-composers, most recently embodied in the late Olivier Messiaen....

And so on. Of course, if the composer is living, it's more difficult, because the only good biographical incidents are either dirty or humiliating, and no living composer will admit to them; in fact, few composers' lives today seem to have much of the really disgusting stuff that makes for good program notes. For Jennifer Higdon I once had to content myself with the fact that she once caught 41 fish in an afternoon's fishing. But I do often get compliments for writing livelier and more absorbing program notes than average, and the tricks I use are easily appropriated. It's a good thing for a young musician to know how to do. Too bad the thought of writing books about conventional repertoire bores me to tears.

(Years ago when I had an piece played by a sub-professional orchestra, I showed the score first to a famous orchestral composer and asked for advice. This esteemed personage suggested three changes - two of which didn't work out in rehearsal, and I had to retract them.)

The problem of writing orchestra music is the same as writing any other kind of music: fashioning a continuity in which the ideas make themselves clear, take time to breathe, and lead from one to another with a plausible logic, resulting by the end in a meaningful and satisfying large-scale shape. Errors in these areas get writ large in an orchestral format, but the orchestra also provides lots of colorful toys to compensate and distract with. Places where the orchestration seems awkward are almost always places where the musical idea wasn't well thought through, and wouldn't have worked any better in a string trio. Writing orchestra music requires a ton of work in checking parts, deciding whether to go solo or "a 2," and so on, but the common idea that only those in some upper echelon with special experience should be trusted with an orchestra is ridiculous.

Titled after an essay by the late philosopher and literary theoretician Jean-Francois Lyotard, Several Silences is a group exhibition exploring various kinds of silence. As a discourse, the aesthetic of silence has been thoroughly domesticated within the visual arts. Although silence as a discourse in art arose out of conditions calling for the negation of art, it has subsequently become familiar subject matter no longer operating as the avant-garde ideal it once was. This is not to say silence has lost significance. If anything, it has become a more potent antidote to a culture of distraction. Silence, however, is not the absence of communication. It is dialectically opposed to communication, so that one sustains and supports the other. Inextricably bound to communication, which it tacitly evokes, silence itself is a form of communication with many meanings. There are voluntary and involuntary silences--some comfortable, others not. There is Cage's silence, which calls for the distinction between clinical and ambient silences. There is silence as conscious omission or redaction. And then there is memorial silence.

"When I hear gentlemen say that politics ought to let business alone, I feel like inviting them to first consider whether business is letting politics alone."

- Woodrow Wilson

a musician of genius ... who died unrecognized and in want on the very threshold of his career. ... It is completely impossible to estimate what music has lost in him. His First Symphony soars to such heights of genius that it makes him - without exaggeration - the founder of the New Symphony as I understand it. To be sure, what he wanted is not quite what he achieved. ... But I know where he aims. Indeed, he is so near to my inmost self that he and I seem to me like two fruits from the same tree which the same soil has produced and the same air nourished. He could have meant infinitely much to me and perhaps the two of us would have well-nigh exhausted the content of new time which was breaking out for music.

By destroying a club with a bulldozer, Eye, in a very direct way, called into question the way music is consumed by the public.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

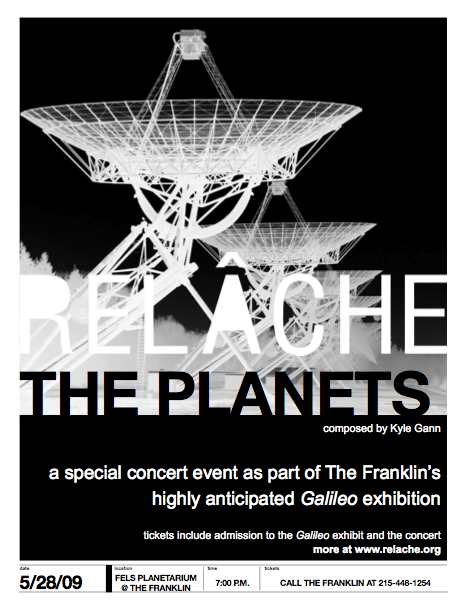

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog