PostClassic: December 2008 Archives

Ben Harper shot back the answer within seconds. Other answers showed considerable originality, and I got a big laugh out of the idea of Cage's book M being about Bond's boss.

Happy New Year. If you need to insult a composer at a party tonight, here's an old classic:

"Your music will be played after Mozart's and Beethoven's is forgotten. And not before."

Last three words sotto voce as needed.

I asked him why and he shrugged and didn't know. But it does subtly look like in the notation on the left the notes are fixed and must be played correctly, while the ones on the right are sort of just the "suggested" notes, and if you can think of something better you're free to substitute something.

Years ago I used to write pieces that did have optional notes, placed in brackets or parentheses. Maybe I should notate them this way.

"There is something rotten here, and we don't have to go to Denmark to look for it. It's not the public. That was always a lie. It's not the mass media. A bigger lie. It's not the capitalist system - another lie. It's my colleagues. My fellow American composers. The most pedantic, the most boring, ungenerous bunch of human beings one can meet on an earth so crowded with the last men that hop and make it smaller and smaller. This earth, I mean.

"It's the college boys that are deciding what's what in America. I'll leave them with their judgement. I'll leave America with my fame."

I'll never forget when at a summer camp a distinguished guest composer came in to give us composers a lesson, and she informed me that my music "lacked that Elliot Carter mentality" and I ought to listen to his entire repertoire again before writing another piece.

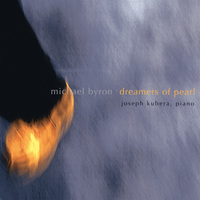

Now, imagine something like that going on, pretty much the same texture and same intensity, for 53 solid minutes. That's Michael Byron's new Dreamers of Pearl (2005), just released on a New World CD by possibly the only pianist who could currently achieve such a feat, human player-piano Joe Kubera. There's a key signature, admittedly, but so many accidentals that it seems more hindrance than help, and the first movement has five flats in the right hand and none in the left. The second movement, titled "A Bird Revealing the Unknown to the Sky," is more sweetly impressionist in its harmonies, but no less intense. You can see that the melodic streams are dotted by some repetition of figures, and some mirroring between the hands, which break the effect of nervous randomness. But it's a relentless, fanatical piece, and I do appreciate musical fanaticism for its own sake, which is why Milton Babbitt was always my favorite American 12-tone composer.

(Incidentally, there are readers who assume that I must froth with venom when I spit the name "Milton Babbitt" out of my mouth. It is true that I have sometimes given Babbitt shit for his articles, which express a subtle contempt for the human race. I'm kind of an optimist, who thinks the human race should be cut some slack, and in particular I think if you find yourself expressing contempt for the entire human race you should take a hard, objective look at your motivations and try to figure out whom you're really angry with, and who hurt you. Babbitt's Perspective articles I've always thought of as a sublimated, mathematically elegant revenge for having grown up Jewish in Mississippi, which I'm sure was no picnic. But if you look at what I've written about Babbitt's music over the last 26 years, on balance it's pretty positive. I especially love his vocal works, and have always said so: Philomel, Vision and Prayer, Du, The Widow's Lament in the Springtime, An Elizabethan Sextette - because Babbitt's Apollonian, exquisitely classical technique, which precludes even the slightest trace of the usual, predictable, "emotive" shaping of phrases, sets off the pathos of his texts with a kind of thrilling understatement, like the best early Baroque opera. I've often wondered, given his impassive rhetoric, whether he even realizes what makes those pieces so special. His All Set is also a brilliant joke, and I've always been attracted to Canonical Forms and the Piano Concerto. I wrote the liner notes to Sextets and The Joy of More Sextets, back when they were on vinyl, you could look it up. I don't think string quartet is a great medium for him, and sometimes, as in Post-Partitions, I think his experimental schemata lead the music outside the realm of perceptual possibility and relevance. But I wrote a long, enthusiastic review of his book Words about Music. When I entered college, as I've said many times, Babbitt and Cage were my favorite composers. So to assume, oh, Kyle Gann's a big Glenn Branca and Phil Glass fan, he must hate Milton Babbit, just haaaaaate him, is a road map leading to gross error. Remember, when you assume, you make an ass out of u and me. But I digress.)

Anyway, Byron is an old cohort of Peter Garland's from the early days, and one thing I admire about both of them is their ability to keep going for long stretches with only a tiny set of materials and no perceptible method. (I wish I had that level of discipline; I generally need some kind of large-scale transformational strategy to make the long haul.) I've nominally known Byron myself for 26 years - I conducted a piece of his at New Music America '82 - but he fell out of the new-music world for over a decade, and has been making an impressive comeback only in the last few years. Easily the most magnificent thing I've heard him do, Dreamers of Pearl is a perfect example of the Absolute Present I wrote about recently. There are no landmarks, no before and after, just a continual present with barely enough mixture of repetition and randomness to keep you thinking you're about to figure it out. Absolutely beautiful, and the subtle differences in character among the three movements are intriguing. Having paid the piece the supreme compliment of listening to it in the car throughout a long road trip, I now upload it to PostClassic Radio. It takes its place among a growing list of massive postclassical piano works: Barlow's Cogluotobusisletmesi, Polansky's Lonesome Road, de Bondt's Grand Hotel, Curran's Inner Cities, Walter Zimmermann's Beginner's Mind, George Flynn's Trinity, and an amazing number of others.

This makes the comments feature something of a problem. The messages I get from people who understand the context of this blog vastly enliven it, and I treasure them. But for some reason, we periodically seem to attract momentary attention from the Conventional Wisdom crowd, who, horrified by a random phrase here and there, write in to portray me as some kind of trance-music Madame Mao determined to bomb classical music back to the stone age. I don't have time or energy to re-explain my entire life story to every rubber-necking newcomer who chances by to ask the new-music equivalent of, "When are you going to stop beating your wife?!" So rather than post those comments, I'm going to try to write a meta-post explaining a few premises of this blog, a series of such posts if necessary, so in the future I can simply refer those people to this URL.

So, for the uninitiated, let me address some myths about PostClassic:

Myth No. 1: I Am Opposed to All Complex, Difficult, and Atonal Music. In the first music history course I took at Oberlin, the professor played Stockhausen's Mikrophonie I for the class with poorly concealed distaste, and it was left to me, a freshman from Texas, to defend Stockhausen to the class as a remarkable and important composer. That was 1973. The first piece I wrote at Oberlin was influenced mainly by Luciano Berio's Circles. The Darmstadt serialist repertoire was the first brand new music I imbibed, and I did so in high school. I absorbed it on my own, to the incomprehension of my peers, uncontaminated by the pressures of mentorship, which is perhaps why my attachment to it never became dogmatic. I guess what happens with most composers, still today, is that some college professor introduces them to serialism, and learning to appreciate it becomes some kind of entrée into the professional world, from which there is no turning back. For me it was a private affair; I felt free to accept from it what I liked and reject what, after dozens of obsessive listenings and all the reading material I could find, I didn't.

Therefore the automatic disdain of the amateur who thinks nothing good can come from 12-tone method, and the automatic reverence of the professional composer for whom 12-tone music was The Noble Experiment, I find equally shallow. My writings on complex and difficult music have been extremely nuanced. I've written with varying degrees of closely analyzed enthusiasm about Roger Sessions, Ralph Shapey, Dallapiccola, Takemitsu, Rochberg, Rochberg again, Stefan Wolpe, Vermeulen, Blomdahl, '50s Carter and '60s Boulez, the ultracomplex music of Mike Maguire, some fanatically complex music by Cornelis de Bondt, rhythmic complexity, complexity in general, 12-tone music again and again. If you can read all that and still claim that I have no deep affection for complex, difficult, or atonal music, maybe it's time to admit that reading comprehension isn't your forte. "I find it rather foolish that we would dismiss all music which simply defies even the sharpest of listeners to catch every detail the first time they hear it," cried a commenter in anguish a few weeks ago. That someone could feel a need to say this to me, of all people, almost extinguishes all hope.

Of course it's probably, as Darcy James Argue says, that the Fraternity of Serious Composers defines themselves in opposition to popular taste, and if you admit to disliking even one complex, difficult piece you are immediately suspected of being an Unreliable Club Member and therefore must be rooted out and rehabilitated. Unreliable Club Member: that I'll plead guilty to. I no more pledge allegiance to minimalism than I do to serialism: I find The Desert Music problematic, Different Trains didn't grow on me, and I've written some of Glass's most blistering opera reviews. I am no ideologue.

Myth No. 2: I Write Music for Audiences. This one is actually true, but with qualifications. Almost every composer, even the regular commenters on this blog, will cite you the Conventional Wisdom about whom one writes for: "I only write for myself, taking my own taste as representative, since there is no such thing as 'The Audience,' everyone listens differently. Complexity is only a subjective perception anyway, and after all I saw Brian Ferneyhough get a standing ovation at Miller Theater once, and posterity will sort it all out, yada yada yada." Of course, you presumably already know what's going on in your music and a stranger listening to it doesn't have that inside scoop, and by trivializing that perceptual asymmetry, this line of thought provides an effortless rationale to save you the trouble of clarifying your ideas to the point that no one can miss the point of your music. On this issue I am way, way, way in the minority, even among friends. But I am not alone. As one of my regulars once responded:

The "I'm writing only for myself"-line I've always regarded as cynical and defensive. It's the art composer accepting his marginalisation by capitalist society, or even trying to pass it off as a great and heroic thing. Nonsense! Even Schoenberg couldn't stomach that. Yes, our art may come out of some sort of composerly ascesis, but it's not meant to stay there!

There is another tradition: that of Aaron Copland in the 1930s when he said, "It seemed to me that composers were in danger of working in a vacuum... I felt it was worth the effort to see if I couldn't say what I had to say in the simplest possible terms." The tradition of Marc Blitzstein who protrayed artists in The Cradle Will Rock as the biggest corporate whores of all, of Hanns Eisler who broke away from Schoenberg to write worker's choruses, of Cornelius Cardew's Stockhausen Serves Imperialism, of Leo Tolstoy's What Is Art? And it is the same tradition, though we didn't articulate it as militantly, as the populist movement that surrounded the New Music America festivals of the 1980s; without getting terribly political about it in the left/right sense, we were excited that a large group of composers had returned from the arid wastelands of the serialist avant-garde to write music that audiences could find hip and exciting again. It is even the tradition of Steve Reich, who wrote in 1967 that "Obviously music should put all within listening range into a state of ecstasy." Perhaps it's populism's tragedy that its two most eloquent apologists, Tolstoy and Cardew, wrote overly extreme, over-the-top books whose excesses are only too easy to refute. Nevertheless, phrases from those books stick in my head, unanswerable, forming part of my musical conscience. Despise me as you will, I compose with the audience in mind.

But I am no extremist, in this or anything else. Put a gun to my head, and I'd say that populism and narcissism are two poles between which an artist should vacillate, satisfying now one, now the other, and that the psychologically effective strategy is not to get stuck permanently at either end. If I am a fascist for believing that there is any worthwhile alternative to narcissism, as a commenter called me, then Aaron Copland was Stalin himself. (And besides, the more historically resonant epithet to throw at me would have been "communist!," which I would have accepted in better grace.) Just as I need not defend complex music, since only simple music comes under attack from the composing community, neither do I need to defend narcissism, which is the catholic church to which all composers subscribe except for a few of us outcast heretics. But I do defend, when the occasion arises, the opposite pole of populism. Some people take from this the uncharitable view that I am irrevocably opposed to selfishness and self-aggrandizement, when, really, it's just that I think it's probably not politic to wallow in them 24/7/365.

If you disagree with me, as chances are you do, I need not hear from you about it. To violently disagree with me on this issue is to be a walking cliché, a stock character: a composer who writes only to please himself. There are 40,000 of you out there at last count. I know exactly what you think, and need no reminder. You will never experience the grace with which Shakespeare could address the audience through the mouth of Prospero, who closes The Tempest by saying,

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please.

(How cynical of Shakespeare to so pretend, since as a great artist he must have known that great artists write only for themselves.) Take comfort in the fact that opinion within the composing community is nigh unanimous on your side. Take no notice of the deplorable situation that new music composition is an art almost completely absent from the world's enthusiasms: surely the fact that composers are trained to write only for themselves bears no responsibility for that. And consider that the attempted squelching of my populist dissent is more fascist in character than it would be to allow me my tiny minority opinion, which threatens you no harm. Which leads us to:

Myth No. 3: I Control What Happens in the New-Music World. How in hell did that one arise? What's with the fear that I'm going to disenfranchise lovers of complex music, that I am on the verge of descending from Olympus and imposing my will on the new-music performance scene? Me?! Does James Levine never pencil a title into his conducting schedule without running it by me first? Are Dana Gioia and I are on the phone daily so I can confirm which composers are up and which are down at the NEA this month? Does the new-music programming of Michael Tilson Thomas and Esa-Pekka Salonen hinge on my suggestions? Do I wave my hand and the complexion of the upcoming concert season is altered?

The world of academic composition is tightly barricaded against people who hold views like mine. My colleagues circle the wagons to make sure my radical ideas don't infect the students. Every year I have to argue that it's OK for student pieces to have only one dynamic level all the way through. My suggestion that students ought to be allowed to learn composition software other than Max/MSP incited World War III. My simplest, most common-sense ideas are too radical for musical academia. Except for a few jokers at Yale who like to live dangerously by exposing students to me, the academic composition world has closed me out. (I occasionally hear that some blog entry of mine is brought into composition class to start an argument with, but it may just be Rob Deemer over and over again.) I used to sit on the occasional composer panel, but haven't been asked in years. No one I've written a Guggenheim recommendation for has ever received one. And as for the world of contemporary music performance, I'm not even a hair on a gnat on an elephant's rump. So what's with this panic that I'm going to rearrange the furniture, and heads will roll? I am at best the Dennis Kucinich of the composing world, considered insightful by some on the crazy left but with views so far outside the acceptable mainstream that there is no chance they will ever be discussed seriously in public by anyone but myself.

The only people who do listen to me - aside from a small cadre of fans whom I like to imagine idling around Other Music in New York waiting for the next Charlemagne Palestine CD to arrive - are the musicologists. I am in possession of historical data for which they have no other current source, and my description of a 1930s populism resurfacing in 1980s Manhattan piques their curiosity, not their terror. The musicologists, realizing circa 1983 that their profession's reputation was stale and dowdy, revolutionized their field, and are now at the apogee of their powers. Composers, by contrast, enjoyed their hour of maximum prestige in the '60s, and are straining every ideological sinew to extend that moment into eternity, and forestall the passage of time. There exists perhaps a real danger that my account of late-20th-century American music will get accepted into the history books in some form or another, for the lack of any attempted alternative narrative. But that's hardly my fault. I wield no weight except for whatever persuasiveness I can muster in prose. I have no institutional support, am buoyed by no prizes or awards of any note. I'm just a blogger, but for some reason a threat to Western civilization.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A friend who got her doctorate in the '90s at a famous music department told me yesterday that the faculty criticized her music for having too many articulated downbeats (notes occuring on the first beat of the measure) and not enough quintuplets. From the point of view of traditional musicality that is absolutely bizarre - imagine Mozart submitted to such criteria - but from the point of view of the composing world's Conventional Wisdom, the "Elliott Carter got it Right" mentality, it makes a certain perverse sense. Some of us find this Conventional Wisdom twisted, neurotic, cramped, dogmatic, fascistic, counterintuitive, self-defeating, and sick. We gather here at PostClassic to get away from it, as gays go into a gay bar, and we don't need academia's Religious Right trailing in after us in to give us the same lectures we're trying to escape from. If you've bought into the Conventional Wisdom, you have the entire rest of the composing world to roam around in, and heads will nod wherever you speak. Why isn't that enough? Why are you compelled to try to change PostClassic too? What is it about a little modicum of marginalized diversity that threatens you so much?

I'm determined not to shut down the comments feature, but I am going to take a heavier hand from now on in deleting comments that demonstrate ignorance of the context here, and would therefore take way too long to answer. Those commenters will be referred to this post, and any other summational ones I feel moved to write. I am not obligated to provide yet another platform for the Conventional Wisdom. If that's all you've got to throw at us, the rest of the classical music world's your oyster, bub.

My own research and study into the quote-unquote avant-garde has revealed two distinct poles. There's the avant-garde of privilege, the avant-garde that primarily emphasizes quote-unquote art for art's sake aesthetics above everything else. Then there's what I would call the populist or the radical avant-garde. In America, I think those two kind of poles happened during the late '50s, and through the '60s and early '70s. I think the privileged avant-garde really wanted to create this wall between social activism, political radicalism, and aesthetic radicalism, whereas there was no distinction, say, between members of the Black Arts Movement and the Black Liberation Movement. The Panthers brought Sun Ra to be a guest faculty member at the University of California in Berkeley. There was a kind of recognition that the politically and artistically radical were two heads of the same coin. I've always identified myself with these movements; expanding humanism requires new forms. It requires new expressions and new vehicles to express those ideas and those feelings. To me, the quote-unquote utilitarian value of the arts of any discipline really is about expanding and deepening human feeling, the human soul, and the human imagination. And that imagination is critical to any progressive political or social movement. I often say that our responsibility is to make politics a creative and artistic process, and to make the arts politically committed. So I've never seen a separation between the role of experimentation and the vanguard role of politics. All those things are inextricably interrelated and mutually necessary.

- Fred Ho, being interviewed by Frank Oteri

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog