PostClassic: September 2008 Archives

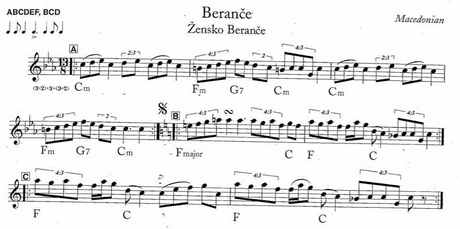

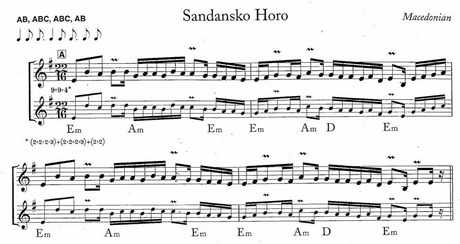

[T]he Bulgarians DO NOT count out every "8th" or "16th" note while performing their music. They express them as long and short beats. They actively discourage trying to count it out, and expressed that the only way to hope to begin to play it accurately would be to feel the long and short beats.

While Meister Eckhart was alive, several attempts were made to excommunicate him... None of the trials against him was successful, for on each occasion he defended himself brilliantly. However, after his death, the attack was continued. Mute, Meister Eckhart was excommunicated. (p. 193)

the problem of why Eckhart himself did not put up a better defense... The years... of paradox-spinning for the scandalized delight of larger but less critical and instructed audiences do not seem to have sharpened his wits... [W]e can perhaps detect signs of the apathetic fatigue experienced by an aging man, aware that he has not fulfilled his early promise and has exhausted his powers in his efforts to woo popular acclaim. (p. 14.)

We've got grad student Jedd Schneider, singer and musicologist, who's written an analytical paper on M.C. Maguire's A Short History of Lounge, and whose contribution to the conference will be a paper on the operas of Michael Gordon. We've got Scott Unrein, the Harold Budd of the midwest, who keeps coming up with minimalist CDs I didn't know existed. We've got pianist Andy Lee, who's playing music by Bill Duckworth. We've got musicologist Andrew Granade, who's writing a book on how Harry Partch's hobo years, and the image of the hobo in American culture, influenced Partch's music. Most amazing of all, the UMKC conservatory has a brand-new dean, conductor Peter Witte (only three weeks on the job), who reads my blog (hi, Peter!) and who knew about this conference even before he applied for the job, and who's fully committed to it. What a cast. And David and I are such Virgil Thomson freaks (he's promised to show me the great man's grave an hour north of KC) that we joked all week about how we were going to slip a panel about Virgil onto the program.

I also met amazing electronic composer/motorcycle enthusiast Paul Rudy, whom students had raved about to me, and who shares my penchant for native American spirituality. Paul makes incredibly beautiful music from musical tones and environmental sounds of widely varying recognizability, and I've uploaded his CD-length work In lake'ch* (Mayan for "I am another yourself") to PostClassic Radio. Paul and I devoutly agreed that there's no line between art and entertainment, and that all good art is entertaining - though he holds the theory, which impressed me, that art = entertainment + ambiguity; in other words, if it's completely unambiguous, it's merely entertainment, but the more ambiguity you add in, the more the listener has to mentally participate to parse what's going on, the more it becomes art. I like it.

And so now I'm so charged up that it kills me that the conference is still a year away. We're featuring Charlemagne Palestine, Tom Johnson, my old friend Robert Carl (keynote speaker, having freshly completed a book on In C), and Mikel Rouse. I spend a lot of time feeling like my view of music is a minority within a minority within a minority, but some of my gigs out there in the heartland lately have made me think that, actually, much of America and I are right in sync, and it's only the dying Northeast that's nostalgically gazing into the past. We talked a lot all week about how, if you're a composer who made out like a bandit in the world of orchestral modernism, then of course you cling to modernism with all your might. But if you didn't really make it in that world - and a lot of those composers ended up out west in KC and other less visible places - you just shrug, move on, and stay abreast of the times. As Paul Rudy said, "We're going through a big paradigm shift, and I want to be on the front end of that shift, not the back end." Amen to that. Still, also at UMKC are orchestral star Chen Yi and high-tech composer Jim Mobberley, whom David credits with for department's incredibly open-minded aesthetic attitudes. There was also independent KC composer Brad Fowler (hi Brad!), whose music I haven't heard yet, but look forward to. Suffice it to say that for a few days I was surrounded by simpatico aesthetic allies, a situation I could never get here in the Hudson Valley. I felt more at home than I have in years. This minimalism conference is going to be an incredible trip.

*By the way, I've also been adding other new music to PostClassic Radio lately by Joseph Pehrson, Stephen Scott's Bowed Piano Ensemble, Rodney Sharman, Carl Stone, the Rara Avis Duo, Mark Hagerty, Guy Klucevsek, Cynthia Folio, James Tenney, and Bernard Gann. If you haven't listened lately, lots o' new content.

I

Oh Galuppi, Baldassaro, this is very sad to find!

I can hardly misconceive you; it would prove me deaf and blind;

But although I take your meaning, 'tis with such a heavy mind!

II

Here you come with your old music, and here's all the good it brings.

What, they lived once thus at Venice where the merchants were the kings,

Where Saint Mark's is, where the Doges used to wed the sea with rings?

III

Ay, because the sea's the street there; and 'tis arched by... what you call...

Shylock's bridge with houses on it, where they kept the carnival:

I was never out of England--it's as if I saw it all.

IV

Did young people take their pleasure when the sea was warm in May?

Balls and masks begun at midnight, burning ever to mid-day,

When they made up fresh adventures for the morrow, do you say?

V

Was a lady such a lady, cheeks so round and lips so red,--

On her neck the small face buoyant, like a bell-flower on its bed,

O'er the breast's superb abundance where a man might base his head?

VI

Well, and it was graceful of them--they'd break talk off and afford

--She, to bite her mask's black velvet--he, to finger on his sword,

While you sat and played Toccatas, stately at the clavichord?

VII

What? Those lesser thirds so plaintive, sixths diminished, sigh on sigh,

Told them something? Those suspensions, those solutions--"Must we die?"

Those commiserating sevenths--"Life might last! we can but try!

VIII

"Were you happy?" --"Yes."--"And are you still as happy?"--"Yes. And you?"

-- "Then, more kisses!"--"Did I stop them, when a million seemed so few?"

Hark, the dominant's persistence till it must be answered to!

IX

So, an octave struck the answer. Oh, they praised you, I dare say!

"Brave Galuppi! that was music! good alike at grave and gay!

"I can always leave off talking when I hear a master play!"

X

Then they left you for their pleasure: till in due time, one by one,

Some with lives that came to nothing, some with deeds as well undone,

Death stepped tacitly and took them where they never see the sun.

XI

But when I sit down to reason, think to take my stand nor swerve,

While I triumph o'er a secret wrung from nature's close reserve,

In you come with your cold music till I creep thro' every nerve.

XII

Yes, you, like a ghostly cricket, creaking where a house was burned:

"Dust and ashes, dead and done with, Venice spent what Venice earned.

"The soul, doubtless, is immortal--where a soul can be discerned.

XIII

"Yours for instance: you know physics, something of geology,

"Mathematics are your pastime; souls shall rise in their degree;

"Butterflies may dread extinction,--you'll not die, it cannot be!

XIV

"As for Venice and her people, merely born to bloom and drop,

"Here on earth they bore their fruitage, mirth and folly were the crop:

"What of soul was left, I wonder, when the kissing had to stop?

XV

"Dust and ashes!" So you creak it, and I want the heart to scold.

Dear dead women, with such hair, too--what's become of all the gold

Used to hang and brush their bosoms? I feel chilly and grown old.

I forgot to tell you, Kyle Gann is going to do my biography. Before I went to Germany he was here for a few days and we had a very pleasant visit. I had never heard of him before, but he brought a cassette of his music, and apart from being very simpatico he is a very good composer.

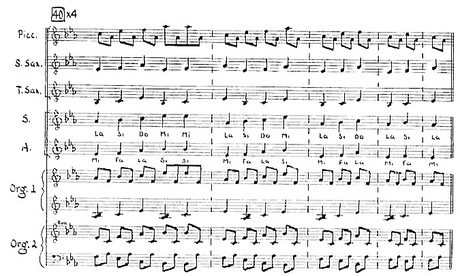

And man, what a blast. Whenever I go through a piece of music I know well with the score for the first or second time, my opinion of the piece either rises or falls somewhat, depending on what I start to perceive in the piece once I fully realize what's going on. Einstein was a vastly important piece from my youth, and while I always loved sections of it, my opinion of the whole has risen noticeably this week. (I had an opposite experience with Glass's later opera The Voyage, a more tedious work than I'd remembered.) Today we went through the "Train" scene in about an hour and a half, and broke it down into an A A' B A" B form - it's the most complex scene from the opera, bringing together two of the recurring chord progressions (there are only about five in the whole four-hour work), as well as running ostinatos of different lengths together, Totalist style - which I may have to start calling Minimalist style. There's a returning transitional passage ("x") between the other sections, so it's really A x A' x B x A" x B, and the three A sections all fall into the same material after awhile, but start out with a different additive-process buildup. (The B sections recur in the final "Spaceship" scene.) In short, the form is both musically logical and satisfyingly intuitive. We had a similar experience with Reich's Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices, and Organ, and I'm not even going to tell you where I got that rare score - one of the prettiest pieces ever made. Much as I love so much minimalist repertoire, I somehow don't expect it to excel in the intuition department, and I'm being pleasantly surprised.

And now I'm pissed off as hell that I had to wait until age 52 to get a score to Einstein, a piece I'd been obsessed with since I was 22. I was wearing out my vinyl discs of this piece nonstop in 1978, and a score should have been available for sale at Patelson's by 1980, so I could have learned all of Glass's (and Reich's) formal tricks before I embarked on my professional career. Instead, I find out that I correctly stole some of their ideas by ear, but there were some other neat formulas that I didn't realize were there. It's criminal that great music can't pass in score form to younger composers within a few years. And it's why I put nearly all my scores up as PDFs on my web site: I refuse to catapult any ideas out into the world without facilitating their immediate theft by young (or older) composers. I may not have any ideas anyone wants to rip off, but I'll be damned if I'm going to squirrel them away out of reach.

I was so transported and wrapt up into High Contemplations that there was no room left in my whole Man, viz., Body, Soul and Spirit for anything below Divine and Heavenly Raptures.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog