PostClassic: August 2008 Archives

The official debut of my blog took place on the 51st anniversary of the premiere of 4'33", the birthday of Charlie Parker, Diamanda Galas, and Mark Morris, and unfortunately on the day of the year upon which, two years later, Katrina would hit New Orleans. At least three of those anniversaries have personal resonance for me. Five years later, I'm a little surprised to find myself still doing it. On the average, I've posted a new entry every two days and 53 minutes, a little short of the vague every-other-day goal I'd set; the shortfall all came this year, but I think I've more than compensated in word count per entry. (Is there any other music blog that goes over the 4000-word mark as often as I do?) I sometimes doubt whether it's wise for me, as a creative artist, to be so omnipresent as a writer. I've probably already joined the ranks of Ned Rorem, Virgil Thomson, and Deems Taylor, composers forever better known for the fact that they wrote words than for their music. A friend commented recently that to get job interviews requires a certain air of mystery, so that people can project on you what they're looking for, and I'm afraid that the weekly public airing of my views since 1983 has left me with no mystery to speak of. Nevertheless, I find writing therapeutic, and this blog allows me a freeform genre of writing that no self-respecting publication would ever support, while my articles - which I would never bother to polish without an audience as incentive - help me organize and, ultimately, change my thoughts. Without this blog my ideas might have gotten set in stone, and would not have evolved as quickly as they have. I am who I am. Like the crazy-going king in The Madness of King George, I occasionally have to speak to get the words out of my head. Sometimes I can't believe anyone reads them, let alone responds thoughtfully. Thanks for doing both.

In order to even begin to understand the music of John Cage, it is necessary to examine some of his most important philosophies and ideas whether you agree with them or not. First of all is his use of silence. Cage considers silence a very integral part of a piece of music, given equal important with the sounded notes. And in conjunction with this I would like to remind you that there is no such thing as total silence, except in a vaccuum; that wherever there are people or any life at all, there is some kind of sound. Cage therefore never uses in his pieces absolute silence, but instead, the varieties of sound such as those caused by nature or traffic, which ordinarily go unnoticed, and aren't usually regarded as music.

Second, and perhaps harder to accept, is Cage's use of noise, or, quote, "unmusical sounds," in his compositions. He does not limit his pieces to sounds produced by conventional instruments. Instead he expands the definition of music, using such sounds as the tinkling of glasses, laughing, and even radios, as elements of composition. Thus his definition of music is the art of music, and not just the art of combining instruments.

Third is Cage's conviction that music should change, that it should provide the listener with a different experience every time he hears it. Because of this he has introduced the element of chance into his music, allowing certain privileges to be taken by the performer, and sometimes even by the audience, so that no one can tell beforehand what's going to happen in a piece. This is done by allowing a performer to play musical segments in any order he desires, picking notes and instruments according to a roll of dice, and even by tuning a radio to a certain station at any particular time. The term for this kind of music is "aleatory music."

Finally, Cage minimizes the importance of the composer. Music, he feels, should not be written down and straightjacketed by a composer. It should be allowed to happen naturally. 4'33" is one of Cage's most famous and most controversial compositions, and it is a showcase for all the ideas I've just mentioned. Those of you who listen with open ears and open minds are about to hear four and a half minutes of completely unintentional and unplanned sound and noise, or, if you prefer to call it, music. Before I allow this music to happen, I would like to mention a quote of John Cage's: "Music is all around us; if only we had ears, there would be no need for concert halls."

Over and over again did the Attorney General cry out aloud, in the agony of his cause, "What is to become of painting if the critics withhold their lash?"

As well might he ask what is to become of mathematics under similar circumstances, were they possible. I maintain that two and two the mathematician would continue to make four, in spite of the whine of the amateur for three, or the cry of the critic for five... It suffices not, Messieurs! a life passed among pictures makes not a painter - else the policeman in the National Gallery might assert himself. As well allege that he who lives in a library must needs die a poet. Let not Mr. Ruskin flatter himself that more education makes the difference between himself and the policeman when both stand gazing in the gallery.

- Whistler, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies

QUESTION: I have noticed that you write durations that are beyond the possibility of performance.

ANSWER: Composing's one thing, performing's another, listening's a third. What can they have to do with one another?...

QUESTION: And timbre?

ANSWER: No wondering what's next. Going lively on "through many a perilous situation." Did you ever listen to a symphony orchestra?...

QUESTION: Then what is the purpose of this experimental music?

ANSWER: No purposes. Sounds.

QUESTION: Why bother, since, as you have pointed out, sounds are continually happening whether you produce them or not?

ANSWER: What did you say? I'm still -

QUESTION: I mean - but is this music?

ANSWER: Ah! You like sounds after all when they are made up of vowels and consonants. You are slow-witted, for you have never brought your mind to the location of urgency. Do you need me or someone else to hold you up? Why don't you realize as I do that nothing is accomplished by writing, playing, or listening to music? Otherwise, deaf as a doornail, you will never be able to hear anything, even what's well within earshot.

QUESTION: But seriously, if this is what music is, I could write it as well as you.

ASNWER: Have I said anything that would lead you to think I thought you were stupid?

Compare with Chapter 27 from Huang-Po's Doctrine on the Transmission of Mind, in John Blofeld's translation:

Q: What is the Way and how must it be followed?

A: What sort of thing do you suppose the way to be, that you should wish to follow it?

Q: What instructions have the Masters everywhere given for dhyana-practice and the study of the Dharma?

A: Words used to attract the dull of wit are not to be relied on....

Q: If that is so, should we not seek for anything at all?

A: By conceding this, you would save yourself a lot of effort.

Q: But in this way everything would be eliminated. There cannot be just nothing.

A: Who called it nothing? Who was this fellow? But you wanted to seek for something.

Q: Since there is no need to seek, why do you also say that not everything is eliminated?

A: Not to seek is to rest tranquil. Who told you to eliminate anything? Look at the void in front of your eyes. How can you produce it or eliminate it?...

Q: Why do you speak as though I was mistaken in all the questions I have asked Your Reverence?

A: You are a man who doesn't understand what is said to him. What is all this about being mistaken?

Cage mentions Huang-Po in the introduction, and includes the Doctrine on the Transmission of Mind in a 1960 list of ten books that most influenced him. But not having read it before, I didn't realize how much of the tone in his '50s writings Cage took from Huang-Po.

If the purpose of American grad school, as I've long maintained, is to teach young people to write badly, then the function of intellectuals in American life is to paralyze discourse. Take the common and useful words subjective and objective. I used to give a lecture on how to write about music in which I would distribute the various types of journalism along a continuum from most subjective to most objective. And some young Turk who'd been in grad school would inevitably pipe up with, "There's no such thing as objectivity, ultimately everything is subjective." Well, OK, that's true, Decartes Junior, physical reality is not utterly knowable or expressible in words, and ultimately the Encyclopedia Britannica is simply an outpouring of the human imagination, and we might as well all get into lotus position and become One with the Universe. But in everyday life, in which people do things for money and get paid and buy food, there are Grove Dictionary entries to write in which one does one's best to avoid foregrounding his opinions, and record reviews ending in thumbs up or thumbs down, and objective and subjective are fine words for describing that quotidian difference. At least, if I were to ask an editor how objective she wanted me to be in an article, and she came back with, "There's really no such thing as objectivity, you know, ultimately your subjective perceptions will reveal themselves in your word choices and emphases blah-de-blah-de-blah," I would consider her something less than professional.

It's much the same with musical uses of complex and simple. (I'm incited to write this by Colin Holter's response at New Music Box to my recent complexity article - not particularly because he says anything I disagree with, but simply because he brings it up and I figured I would have to address this eventually anyway. Such are the obligations of blogging.) We have everyday things we mean when we say a piece of music is simple, or that it's complex, but ahh, these meanings are never good enough for our musical intellectuals. What rings in my mind is a line from Richard Toop's 1990 lecture "On Complexity," published in Perspectives:

People sometimes ask, ingenuously or otherwise, "Why do composers today want to write complex music?" Looking at the broad history of Western music, I would be tempted to reply, equally simplistically yet not inappropriately [what a grad-school-induced useless phrase], "When have the talented ones ever wanted to do anything else?"

You can just see the smirk, can't you? Well, OK, a Beethoven sonata is a complex thing. Lots and lots o' nested relationships there, and you can tease them out forever, and people have. But back when I was 16 years old and had a memory, I could play through a Beethoven sonata movement twice from the score, and then play it the third time from memory - because its progression was so clear and logical, so honed down to a single elaborated thought, that my memory could grasp the thing as a whole. By contrast, a shorter Chopin nocturne took twice as much effort. So you can prove to me with Schenker diagrams and motivic derivations that a Beethoven sonata is complex, but boy, when I was 16, I certainly don't remember experiencing it as complex. If anything, its simplicity was kind of overwhelming. Meanwhile, George Rochberg's wonderful Sonata-Fantasia, a sprawling 12-tone piece I was also working on - no contrapuntally thicker than much Beethoven - was not something I was ever going to be able to commit to memory. Nor did I ever quite memorize "Thoreau" from the Concord Sonata, a piece I dearly love. Sophistry can make a case that those pieces were no more complex than Beethoven, but they sure seemed more complex to me.

I know, good lord I know from measureless experience, that the moment you describe a piece of music as complex, a raft of the grad-school boys, the Swift Boat Graduates for Obfuscation, rise up and say, "Welllll, nowwwww, ultimately all music is complex, and isn't a Bach fugue complex, and isn't the brain processing lots of information as a Debussy tone poem goes by, and so what's the difference between the Carter Double Concerto and a Satie Gymnopedie, really?" So that cuts off discussion, which is its purpose - to prevent certain obvious issues from being talked about. And so in my blog entry, with great rhetorical deliberateness, I almost never used the word complex in isolation, but fused it into "thorny, complex, difficult-to-understand," or "complex/opaque." I was specifically trying to prevent the Swift Boat Graduates from playing Gotcha!, and I was pleased that there wasn't much of that. (In the interest of refusing to discuss complexity as a monolithic concept, McLaren added a long, revelatory comment about the perceptual constraints on audio complexity that's well worth reading. He's a brainy guy, not academic. There's a difference.)

The denotation I wanted for the word complex in that article was exactly the distinction I experienced at 16 between Beethoven and Rochberg: that some music gets stored in the mind very quickly and in great detail, and other music resists such storing. No value judgment intended - I was just as excited about working on Rochberg at 16, if not more, than I was on Beethoven. Nor - and this seems so bloody obvious that to have to mention it fills one with a certain despair about how pedestrian the level of our musical discourse is - nor is complexity level a monolinear continuum. Satie's Pieces Froids are far simpler than Beethoven's Appassionata in form and texture, but they are more complex in being less logical and therefore more difficult to memorize. There are a hundred or more types of musical complexity. I was trying to write about perhaps the most obvious of those types without writing a second article to clarify what I was referring to. Didn't work.

Of course, the Swift Boat Graduates always have a point: a lot of complex things go on in the brain in response to a Satie Gymnopedie, and ultimately the Encyclopedia Britannica is just a record of billions of subjective impressions upon which doubt could be cast. Those are interesting, important issues to ponder, but they are rather divorced from everyday life, and few of us can afford to leave everyday life for long. Subjective, objective, complex, simple, are all comparative terms whose absolute endpoints lie outside human experience; and if you're going to swallow up those words into their intellectually derived absolutes, then we still need other words for the everyday meanings those words hold in conversation. What's wrong with the Swift Boat Graduates is that they sometimes wax fascistic about disallowing naive uses of their pet words, as though once you've discovered a more sophisticated concept for the word, what the naive use once referred to disappears. This tendency threatens to bring musical discourse down to a grad-school level. Part of intellectual maturity is knowing when the exalted meaning is appropriate and when the quotidian meaning is just fine.

As a philosophy student I spent years immersed in existentialism and Continental phenomenology, taking courses in Heidegger and Husserl and Merleau-Ponty and ranting about the ding-an-sich and the quasi-for-itself and the at-hand, and terrorizing my friends with this invented terminology everyone had to learn just to talk to me. At the end of grad school I learned about the ordinary language philosophy epitomized by John Wisdom (that's his name, no kidding). Much like minimalism, it came as a breath of fresh air. One of my former Bucknell colleagues, Richard Fleming, does ordinary language philsophy, and gave a brilliant lecture once on the question, "Can computers think?" His rather Wittgensteinian strategy was to insert the word computer into common phrases using the word think:

Can a computer think again?

Can a computer think better of something?

Can a computer think badly of someone?

Can a computer think it's right?

And so on, the upshot being that the word think in everday use has a hundred connotations, only a handful of which can be applied to a computer, so, of course, in any reasonable, public sense of the word, a computer can't think. His argument was more elegant than my cursory reiteration of it, but the point is that I similarly refuse to restrict subjective, objective, complex, simple, to their elevated grad-school uses. It aggravates the Swift Boat Graduates, but if we're going to connect the music we love with the world we live in, it's not helpful to get in the habit of justifying ourselves with a special, circumscribed vocabulary. That way dishonesty lies.

Researching 4'33", I ran across a statement about harmony by Cage which I think bothers me more than anything else he ever said:

I now saw harmony, for which I had never had any natural feeling, as a device to make music impressive, loud and big, in order to enlarge audiences and increase box-office returns. It had been avoided by the Orient, and our earlier Christian society, since they were interested in music not as an aid in the acquisition of money and fame but rather as a handmaiden to pleasure and religion. ("A Composer's Confessions," 1948)

Geez, John, just because you had "no ear for harmony," those of us who do have one aren't supposed to use it? And if we use harmony to make our music "impressive," that's automatically for money and fame rather than pleasure? Isn't giving pleasure what sometimes tends to bring money and fame? I've never read anything else of his that left such a bad taste in my mouth.

Nice interview by Daniel Wakin in today's Times with one of my favorite oddly low-profile composers: Paul Lansky. The money quote: "I basically don't like electronic music. I like to compose it. I'm just not a big fan of it." And yet, no one has done more than Lansky to demonstrate how seductive, engaging, and memorable electronic music can be. Maybe it takes someone who doesn't really like it to bring out its best potential - just like I think I'm a good theory teacher because I don't really take theory seriously. There are areas of human endeavor in which, if you fall for the company line, the results can be too deadly earnest.

It is sometimes suggested, as lately, that I have a classical elitist's antipathy toward pop songs. In fact, I have often mentioned that my early music was heavily influenced by Brian Eno, but perhaps I've never said it entirely in caps. FROM 1978 TO 1984 I WAS RATHER OBSESSED WITH BRIAN ENO, BUYING EVERY RECORD HE PUT OUT - WHICH I STILL DO (JUST A COUPLE OF WEEKS AGO I ACQUIRED BEYOND EVEN, HIS LATEST COLLABORATION WITH FRIPP, RELEASED LAST FALL) - NOT ONLY HIS AMBIENT ALBUMS BUT HIS POP ALBUMS, AND I ALSO CHECKED OUT EVERYONE HE COLLABORATED WITH, PARTICULARLY FRIPP, CLUSTER, AND BYRNE. Short of tattooing "Blank Frank is the messenger of your doom and your destruction" or "More for me, bless my soul" on my forearm, I don't quite know what else to do. If being able to sing from memory all the lyrics to Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy, Here Come the Warm Jets, and Before and After Science isn't enough to kill this elitist reputation, then you just want to think ill of me, so go ahead.

I shook hands with Eno once, at the 1988 Composer-to-Composer Festival at Telluride. There was a beautiful woman standing just behind me, so Eno and I didn't actually make eye contact. He had showed up at the festival a couple of days late, and in the meantime, Lou Harrison and Terry Riley had enjoyed some wonderful public discussions about microtonality - different kinds of scales, the problems of retuning a piano, gamelan tunings, and so on. Eno arrived, and was on a panel with the other composers. Someone mentioned microtonality, and Eno instantly blurted out, "Ohhh, microtonality, that just produces a lot of good theory and a lot of bad music." Every composer's eye in the house shot toward Lou and Terry, who exchanged commisserating glances.

This is relevant to the reactions (not only mine) to the recent Byrne article. I yield to few in my enthusiasm for Eno - but I can't help but be aware that, personally, he is too high up in the musico-social stratosphere to deign to notice that he was on stage with two of America's greatest composers who just happened to be microtonalists, and that he insulted their entire outputs with an offhand comment. I'm not mad at him, I still listen to and imitate his music (I just finished a month's repeated listening to his The Plateaux of Mirror with Harold Budd - an album I prefer, by the way, to Bush of Ghosts, sorry). But for all his experimental-music street cred, which I find vastly impressive, Eno is a pop elephant trampling on us poor classical ants without noticing it.

Likewise, I think of Byrne as one of the good guys, his blog often full of populist common sense - I quoted it approvingly during the internet radio crisis of 2007 - and I maintain that I treated him respectfully. But you see how casually he dissed and dismissed two entire genres of composers, and the fact that he does have experimentalist bona fides doesn't ameliorate his minor sin, but makes it the more insulting. I was not moved to think, as some apparently did, "Well, Byrne sure made all us classical composers look like self-deluding losers, but since he's such a creative experimentalist himself, I guess that's just fine!" He ought to know better, just as Eno should have in 1988. But these guys - wonderful, creative human beings though they may be in general - are not focused on us postclassical musicians. We are way too far down in the dirt beneath them for it to even occur to them what effect they might have on us, good or bad. Thank goodness we at least have the right to disagree with them - though some in the blogosphere are telling me that's not true either.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

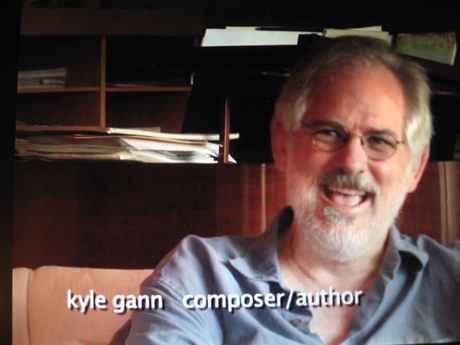

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog