PostClassic: February 2008 Archives

No obituary I've seen for the record producer Teo Macero (1925-2008) has mentioned that he was also a composer, though the Times notes that he studied with Henry Brant. I offer the only piece I've heard of Macero's, One-Three Quarters (sic): a six-minute quarter-tone piece for two pianos and ensemble from 1968. It's pretty cool. It was on an Odyssey vinyl disc, with Ives's Quarter-Tone Pieces and other 24tet works.

As a just-intonationist, I officially disapprove of quarter-tone music and would never write any, but I harbor a secret affection for it anyway. My music starts to sound all too normal after awhile, but quarter-tone music just never stops sounding weird.

UPDATE: Tom Hamilton sends a link to recordings of Macero's music. I always feel bad making a big deal out of a composer just after he dies. That's why I've devoted the bulk of my musicology work to living composers while they're around to appreciate it.

No comment. Completely speechless, in fact.

UPDATE: For that matter, you can market aleatory music and totalism, too.

As an introvert who grew up as a classical musician in Texas, I tend to apologetically assume that everyone in the world knows more about pop music and jazz than I do. For instance, I didn't read Miles Davis's incredible autobiography until I was in my 40s, while I assume any hip musician would have read it in his 20s if not earlier. (The fact that I was 34 when it was published does not allay my suspicion.) But it appears that not everyone knows the context in which Miles referred to classical music as "robot shit," and the story - heavily underlined in my own copy of the book because it had so much relevance to my own experiences, and made me feel so good - is worth retelling as often as possible. The occasion was the recording of Davis's and Gil Evans's Sketches of Spain, for which they hired some classical brass players to play some of the background parts:

...I just went to Gil and told him, "Gil, you don't have to write music like that. It's too close for the musicians to play. You don't have to make the trumpet players sound like they're perfect, because these trumpet players are classically trained and they don't like to miss no notes no how." So he agreed with that. In the beginning, we had the wrong trumpet players because we had those who were classically trained. But that was a problem. We had to tell them not to play exactly like it was on the score. They started looking at us - at Gil, mostly - like we were crazy. They couldn't improvise their way out of a paper bag. So they were looking at Gil like, "What the fuck is he talking about? This is a concerto, right?" So they know we must be crazy talking about "play what isn't there." We just wanted them to feel it, and read it and play it, but these first ones couldn't do that, so we had to change trumpet players, and that's why Gil had to reorchestrate the score. Next we got some trumpet players who were both classical and could feel....

Then we had to have some drummers who could get the sound that I wanted....

...Legit drummers can't solo because they have no musical imagination to improvise. Like most other classical players, they play only what you put in front of them. That's what classical music is; the musicians only play what's there and nothing else. They can remember, and have the ability of robots. In classical music, if one musician isn't like the other, isn't all the way a robot, like all the rest, then the other robots make fun of him or her, especially if they're black. That's all that is, that's all the classical music is in terms of the musicians who play it - robot shit. And people celebrate them like they're great. Now there's some great classical music by great classical composers - and there's some great players up in there, but they have to become soloists - but it's still robot playing and most of them know it deep down, though they wouldn't admit it in public.

So you have to have a balance on something like Sketches of Spain, between musicians who can read music and play it with no feeling or a little feeling, and some others who could play with real feeling. I think the perfect thing is when some musicians can both read a musical score and feel it.... [pp. 243-244, emphases added]

Just like Downtown music. Just like Downtown music. Do you hear what I'm sayin'? JUST LIKE DOWNTOWN MUSIC. Not that you have to be able to improvise, but that you have to be able to feel a musical score, not just replicate the marks on the page.

And as for you, Mr. Edgard "Feel-sorry-for-me-I'm-a-misunderstood-genius" Varèse, you who insists that every note in a score has to have multiple dynamic and articulation marks on it: Why? To turn it into robot shit, to prevent musicians from deciding how they feel it. Because otherwise [in the most simpering possible French accent] "zey do not know how zay vant zere museek to soooooouuuuund." Well, fuck you, Varése. Fuck you and your pseudo-scientific approach to music. (And while I'm at it - Octandre: nice piece.)

That felt good.

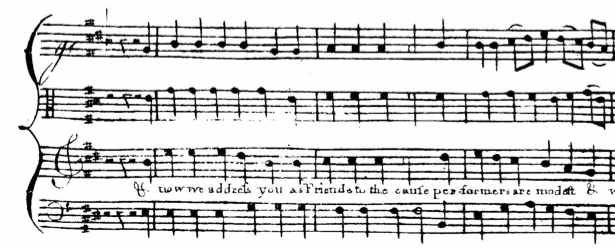

I love this score layout from William Billings's hymn "Modern Musick" from The Psalm-Singer's Amusement, originally published in 1781, a reprint of which I picked up at a used book store this week. Notice how the sharps in the key signature are written as much as possible straight up in a line, F-C-D-G:

Notice too how the note-stems are all on the right, and the treble clef in the soprano is indicated by a "g" on the second line. For awhile in college I wrote my treble clefs that way myself, on the reasoning that a treble clef is just an ornate Baroque Italian G written around the second line, and there was no reason for us to go on writing a "g" in that ridiculously festooned manner 300 years later when even the Italians don't write them that way anymore. I had to choose my battles, I was destined to become engaged in so many, and I rather quickly gave that one up. But I love the insouciance with which the sacred order of sharps in a key signature is ignored, and how little difference it makes in reading the music.

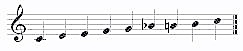

So many conventions of notating music we take as sacred, ancient, and unalterable are actually of relatively recent vintage, and used to be quite malleable. In Bach's day the customary way of indicating a minor key indicated what we now think of as Dorian mode; for a violin suite in E minor he would notate two sharps, F and C. Nowadays, of course, we "correct" him, for old Bach clearly hadn't taken first-year theory class. In the 1890s, theory textbooks (Rimsky-Korsakov's, for example) taught the "harmonic major" scale:

based on the idea that the minor iv chord had become so common in major as to necessitate a special scale. Fashions come and go, theoretical premises change, but we teach notational conventions as though they are somehow ontologically necessary, and browbeat young musicians into a terrified conformity to which Billings was happily oblivious. Why? For efficiency's sake, so that none of our orchestral musicians will ever have to encounter a piece of music that doesn't look pretty much like every one they've ever seen, which otherwise might force them to actually pause and think a moment.

I had a friend many years ago, who died at a tragically young age. Bill Hogeland will know who I'm talking about. Right out of Oberlin she got a job as bassoonist for the Dallas Symphony. I saw her one morning, and she was tired because, she said, the orchestra had performed the night before.

"Oh, what did you play?," I asked.

"Ummmm... Mahler, I think."

She was a sweet young conservatory product, but her conception of her job was to prepare her reeds, sit down in her chair onstage, and expertly and automatically play the notes on the page some functionary had placed on her music stand, without ever thinking about who the composer was or what the notes meant. And to make sure that such nice people never have to think, never have to pause a moment and figure out anything they haven't seen a million times before, our young composers have to have notational conformity beat into them on pain of excommuncation from all decent musical society. Yesterday a student brought me an orchestra piece with the following rhythm:

![]()

It's a perfectly nice rhythm of a kind I might have well used myself. But not in an orchestra piece you don't! I knew enough to put the kibosh on that. Because efficiency, sight-reading, automaticness, and thoughtlessness are at the heart of turning out classical music, that hallowed repertoire that Miles Davis so aptly termed "robot shit" - because it was played by robot musicians who couldn't be bothered to deviate from or even think about what they saw on the page.

Don't bother writing in to tell me how communist and retarded my opinions are, 'cause I already know what the robots think of me. I'm an evolutionist, who thinks music has evolved and has a right to keep evolving, whereas most classical musicians are creationists who think Beethoven created it 200 years ago and it has to stay that way eternally. As Mark Twain said, "I don't give a damn for a man who can only spell a word one way."

This Thursday at 2:30 I'm delivering the Poynter Fellowship lecture at Yale University. I'll be illustrating the problems of my career by mixing up musicology, microtonal theory, and composition in one big indecipherable melange, with some rare scores and manuscripts by Nancarrow, La Monte Young, and myself and my contemporaries. It's at William L. Harkness Hall, Room 207, 100 Wall Street, reception to follow. See ya there.

To serendipitously follow up on my post about publishing and the unavailability of scores, I had dinner with a friend tonight who's a tremendously successful composer, scads of orchestral performances, awards out the wazoo, you name it. And he's telling me how he abandoned his big-name publisher, bought a fancy Xerox/scan/printing machine, and is publishing his own scores, with the same kind of binding and exactly the same quality he got from his publisher. He's sick and tired of people not being able to get his music, or having to pay outrageous prices merely to rent it. And his publisher is nervous and wants a meeting, because my friend hasn't sent them anything in four years. It's kind of delicious. So if you were thinking of trying to get a commercial publisher, or fuming because you don't have one - just forget about it. "What do they do for me?," he kept asking. And there was no answer.

I note with pleasure that my old friend Bill Hogeland, my only college pal I'm still regularly in touch with, got to write the Times's op-ed piece on George Washington for Presidents' Day. Bill, a brilliant novelist and playwright, has taken on a career as historian of American politics much as I've redefined myself as a historian of American music. Seems to be where the money and respect are.

The longest I've ever gone without seeing Bill is maybe six or seven years, once. But regardless, when we meet we immediately resume the thread of whatever conversation on aesthetics we were last having, as though the interruption had been momentary. As Kurt Vonnegut would say, he's a member of my karass.

A non-composing new-music enthusiast writes in with an urgent question:

It is often nearly impossible for an ordinary person to obtain contemporary scores. I've written to composers that you mention without success (or often, without even a response). Why do we need to be Kyle Gann or eighth blackbird to get contemporary scores, even (or especially) when recordings are available?

Amen, amen. How can we keep up a civilized discourse about new music today, even when we can get the recordings, when we can't find the scores on which the recordings are based, and of which they are, after all, only one possible interpretation? I constantly bug composers for scores, and, ironically, it's the ones whose music is published that are the hardest to come by - I can only get perusal scores for a short time, and they take forever to arrive, and so on. I will point out that a very good collection of recent scores, including mine, is available for low prices at Frog Peak, a wonderful company that supports artists and is not trying to enrich itself. But we need some kind of central score warehouse that people can put their work into. The now-defunct and much-lamented IMSLP looked like it might partly serve that function. I scan a lot of the scores I get into PDFs so I can take them on lecture tours and work on them away from home, but I can't go handing those out without some arrangement with the composers. Fifty of my own scores are downloadable on my web site, and very good San Francisco composer Erling Wold does the same. Send me notice of others who do this, and we'll make a list. It's great that making recordings and mp3s at home has become so easy, but the decline of score culture, in sharp contrast to my youth, has been a bee in my bonnet for a couple decades now. Suggestions welcome.

And further to the point, I've now put up a score to my vibraphone solo Olana (PDF download). Several people had asked about it, and I am given to understand that the mallet world is desperate for new repertoire. I often feel I can't get my music played as mellowly as I want it, so I have even introduced into the score the word mellissimo - for those who would feel so much better if I would only use Italian terms.

The opportunity to speak in an endowed musicological lecture series inspired me to talk about musicology itself for the first time in my life. I felt like I was going out on a limb a little, but these are thoughts I'd been having about what we need from musicology lately, and I hoped that some young musicologist or two might see this as an opportunity to return to the cause of new composed music, and do some much-needed good. In that spirit I post it here for a wider audience. The topics are pluralism, minimalism as a new historical era, and the problem with calling American composers "mavericks."

* * * * * * * * * * *

One night in New York City after a concert I was having a drink with my fellow composer Larry Polansky. He was talking about the musicological and restorative work he was doing on music by Johanna Beyer and Harry Partch, I spoke of my analytical writings on the music of Conlon Nancarrow and Mikel Rouse. Finally, Larry said, "Composers are now doing the work that musicologists used to do, while the musicologists are all off doing gender studies."

I am a composer, and have been composing music continuously since the age of 13. I have three degrees in music composition, and none in music history. And yet I have published two musicology books and quite a number of musicological articles. I was even hired at Bard College as a musicologist, not as a composer. I've presented papers at meetings of the American Musicological Society. I have always had a rather fanatical interest in music history, but I have no specific training that could be called musicological. I always go to musicology conferences half expecting to be exposed and thrown out as a charlatan, and the fact that it has never happened has led me to think of musicologists as being universally generous and good-natured people with a shrewd sense of humor.

That I am invited here today to give the Rey M. Longyear Musicology Lecture certainly preserves that impression. When I started college, the first music history textbook I was assigned was by Dr. Longyear, so my consciousness of the honor of the invitation is wrapped up with some very old memories.

But I never had any particular ambition in the field of musicology, and as my anecdote about Larry Polansky suggests, if the needs that composers have from the world of musicology were being satisfied by music historians, I probably would never have ventured into the field.

Several years ago Wiley Hitchcock, who passed away recently, asked me to write a final chapter, "Music Since 1985," for the fourth edition of his textbook Music in the United States. Several months later, we had lunch, and he broke it to me that he wasn't going to go ahead with a fourth edition. No one wanted to read narrative history anymore, he said, everyone was doing gender studies and reception histories and sociologies of vernacular music. "But Wiley," I argued, "just because people are doing all those worthwhile things doesn't mean that we can quit doing what music historians have always done. If someone doesn't write down the basic facts of what's happening, there won't be any contemporary accounts of history for future gender studies scholars to work from." I like to think I brought him around, and the fourth edition of Music in the United States did eventually appear.

There is a perception abroad that in the 1980s musicologists dropped the ongoing narrative of composed music, and when a narrative is discontinued, an impression is created that the story has ended. We composers need musicology, for an objective view of our field from the outside that can create a narrative that will make our activities make sense to the outside world and to ourselves. But for all the good that gender studies, reception histories, ethnomusicology, and histories of vernacular music do, the near blackout of attention to contemporary composing creates a public illusion that the new creation of classical music has come to an end. One reads a lot of dire warnings these days about the death of classical music, and if anything in the world could finally kill classical music, it is this illusion.

What I have to contribute to musicology is data and insights from the composing world, and I would like to use such evidence today to make suggestions on how to get the narrative going again. Literary critics talk about the "master narrative," the large story behind all the individual stories that largely goes unstated and unacknowledged. Stories that contradict the master narrative often go disregarded, all the more so because the narrative itself has never been made conscious or explicit. I'd like to talk today about three narratives, two master narratives and one more explicit, that prevent the world from getting an accurate view of what's going on in composed music today, and ask for your help in replacing them with livelier and more accurate stories.

LEXINGTON - Wow: never have I gotten a welcome like the one the University of Kentucky music department gave me. I was brought here on two pretexts, to give the Rey M. Longyear Musicology Lecture (which I'll post shortly), and to have my new vibraphone piece premiered by Andy Bliss. And it turns out that UK is one of the country's leading, if not the leading, percussion schools, due to the presence of percussion guru James Campbell. Who knew? They've got 30 percussion majors here, 24 undergrad and 6 grad, and four of the sophomores (Michael Hardin, David Hutter, Andrew Jarvis, Logan Wells) nailed my percussion quartet Snake Dance No. 2, as well as it's ever been played. So I've been hanging out all week and learning percussion tricks I didn't know about, from Andy and percussionist-composer Brian Nozny (whose music I'll add to Postclassic Radio soon), and others. Among other performances, student Ryan Nestor gave a dynamite performance (memorized, which blew my mind) of Michael Gordon's XY for five drums, with which I hadn't been familiar. Great piece, a 15-minute totalist polyrhythm fest that transcends the style. For his upcoming recital, Andy's group is working on David Lang's Cheating, Lying, Stealing, so these students are more up to date in American music than any I've seen in ages. And with the extremely gracious musicology faculty I've been discussing Cavalli operas, Nono's politics, Anthony Philip Heinrich ("the Beethoven of Kentucky"), and astrology.

That's my life: fly all over the country learning technical stuff from young people, and getting paid to do so. Who knew there was such a job description?

LEXINGTON - Yesterday I spoke at a graduate musicology seminar at the University of Kentucky. The professor, Lance Brunner, bade me not prepare, and used a method for directing class discussion that I recommend to others. The group had been reading my book American Music in the 20th Century, and he had each person prepare a question, the questions all asked in turn without being immediately answered; after which discussion could proceed with all the questions in mind. One question was, did I think complex music like that of the New Complexity guru Brian Ferneyhough had the potential for reaching a larger audience? Can pop music be saved? How much did I, as a composer, believe in keeping the audience in mind while composing? How relevant were Uptown/Downtown issues to a music scene like that of South America? Did the nature of what we think of as "art music" need to be redefined? I can't remember them all, but as we went around the room, it dawned on me that all the questions were really one urgent question: What kind of music can survive in a corporate dictatorship?

So it was possible to address them all within one framework. I quoted Cornelius Cardew: "Access to [the] audience (the artist's real means of production) is controlled by the state." We used to think the state was the government, but it's now become obvious that the state, in the U.S. at least, is the corporations that own and control the government, and the state's only interest, musically speaking, is in providing mass distribution to the music that can make the most exorbitant short-term profit, and squelching any musical outlet that threatens to pose competition to that profit. In this respect, Brian Ferneyhough, a cutting-edge pop band, and the most sincerely populist composer alive are basically all in the same boat, because integrity itself, however intellectual, musical, or social in origin, is a quality that impedes corporate profit.

What's left is, between the musician and the faraway audience lie a number of hurdles which can act both as barriers and facilitators. There is the cadre of performers who are looking for new music to champion; there are the powerful composers who program festivals and determine commissions; there are the small record labels still idealistic enough to take a chance and lose money on music they believe in; there are the huge record labels willing to take no chances at all; there are expensive managers with their hamfisted and usually misdirected assaults on the corporate publicity machine; there is the democratically all-accepting internet, with its inefficient, hit-or-miss navigation layer; there are small, independent performance spaces of limited outreach; there are the critics who, if they "get" your message, might slightly amplify its scope; there are the rare musicologists interested in organizing, within the shadows of academia, how we think about the current music scene and its direction.

Depending on where your musical talent lies and what kind of music you believe in, each of us has to strategize which of these barrier-facilitators might help us, whose self-interest or altruism we might successfully appeal to. Someone might write the kind of music that flatters, without threatening, the compositional ruling class; someone else might write music that performers enjoy playing; some might have a spiel that critics find intriguing; someone else might play the internet lottery and get lucky. An elitist and a populist would certainly choose different paths through the socio-musical pinball machine, and there's little reason one might not be as successful as the other. And the aim is the same in every case, to manage a small, self-sustaining career in the margins of this corporate-determined life where mass attention is focussed on cultural phenomena none of us can or need respect. (Even the South American question was relevant, because in European and other countries where the government actively promotes cultural activities, a whole different set of strategies apply.)

In other words, the question for all of us is, how do all of us live the kind of rich, rewarding cultural and spiritual life that we deserve to have, that we used to have more of, that we know we could have, in the wake of this corporate behemoth that seems hell-bent on destroying the world for its own monetary enrichment?

Arthur Sabatini, Elodie Lauten, Bill Duckworth, John Luther Adams, Trimpin, me, just prior to jumping on our motorcycles and roaring off into the Seattle night for a feverish orgy of debauchery and destruction from which the city would never recover. Photo by Tamara Weikel (DJ Tamara).

I would like to write something about my new piece Kierkegaard, Walking: not to draw attention to it, but because of a technical aspect of the work that I think draws together a number of late-20th-century influences and says something about the extent to which musical ideas can be style-independent. On a personal level, this is to fill in gaps in the lengthy drinking discussion John Luther Adams had the other night about our respective premieres, and also to clarify for anyone curious that my new piece does indeed intend to do what it seems to do. Consider this a kind of extended wonkish program note of the kind I would write if I assumed audiences had infinite patience and infinite interest in the details of the composer's creative process.

Scene 1: Almost anyone who would be reading me knows what happens in the startling ending of Morton Feldman's Rothko Chapel: it is one of the most famous effects in recent music. For some 15 minutes we've been immersed in a splintered sound world whose disconnected images at least seem homogenous in style and origin. Dissonant chords float by with the pulselessness of clouds; beatless soprano and viola melodies emerge from the distance, and occasionally a hesitant timpani pulse pushes against the grain of the meter. No one at the premiere (or listening to the recording when it was new) would have failed to understand this as a continuation of the soundworld of the 1950s avant-garde.

But suddenly - you know what happens - a vibraphone picks up with a cheerily repeating G B A C motive that sounds like it belongs to a different piece, a different composer, a different era. (In his Seattle talk, Alex Ross connected it to a motive from Stravinsky's appropriately neoclassic Symphony of Psalms, and noted that Feldman was working on the piece the day of Stravinsky's funeral.) One might as well have Winnie-the-Pooh and Piglet skipping onstage in the fifth act of Macbeth. The dark poignancy of the first 15 minutes of the piece is unveiled as artifice, as fiction. The contingency of an ostensibly "natural" style is frankly admitted, one's suspension of disbelief dispelled. It's a magnificent sucker punch, one of the great postmodern gestures.

This is not the only place in which Feldman ends a piece by opening a door that leads the listener out of his soundworld and back into the real one. In Why Patterns? the three instruments play for half an hour in mutually oblivious time worlds, parallel lives. Then at the end, after each has exhausted its material, they quietly fall into regular 3/8 meter and descending chromatic scales. Following the predictable weirdness of Feldman's universe comes a passage so obvious, so banally normal, that no other composer would have ever dared pen it.

Scene 2 of our story takes place in the same decade, but musically in a very different location. George Rochberg, in the 1960s, had started writing pieces that juxtaposed fragments of incommensurate styles: bits of Mozart, Mahler, Webern, Miles Davis butting up against each other like someone twirling the radio dial. (One might note a brushing similarity with Cage's Variations IV.) A couple of years after Feldman wrote Rothko Chapel, Rochberg embarked on a series of string quartets for the Concord Quartet which went beyond quotation of famous works to writing in historical styles. Beethovenesque fugues lurch into Bartokian atonality, giving way to Mahleresque pathos or the Baroque French overture idiom. Though it was initially met by a flurry of some of the harshest professional outrage ever elicited by mere music, Rochberg's gesture emboldened others to strike out in this direction as well, notably William Bolcom and John Corigliano. Bolcom's Fifth Symphony has the time of its life counterpointing the hymn "Abide with Me" and Lohengrin in a Mahleresque funereal style, then breaking into Tristan's Love-Death Music reinterpreted as a fox-trot.

For musicians, this was postmodernism, as far as we understood it on our terms: the fracturing of the organic stylistic unity that one had always considered an inviolable premise of any work of art.

Scene 3: For my late and lamented colleague Jonathan Kramer, the problem with the Bolcom/Rochberg type of postmodernism was that it almost necessarily degenerated into potentially satiric collage, a kind of high-class P.D.Q. Bach. Jonathan was obsessed with this aspect of postmodernism. He didn't live to quite complete his book Postmodern Music, Postmodern Listening, but I've read the manuscript, and people are working on it; when it finally appears, the book will revolutionize the way musical postmodernism is understood. For Jonathan (though this is not strictly to our point), postmodernism is not so much a quality of musical works as a kind of listening potential which some pieces of music encourage more explicitly than others.

After Jonathan's early postminimalist phase, he began pursuing the postmodernist idea creatively. In 1992-3 he wrote a superb piece called Notta Sonata which constituted a critique of Bolcom and Rochberg just as surely as Kierkegaard's Philosophical Fragments constitutes a critique of Hegel. Notta Sonata is for two pianos and percussion, intended as a companion piece to the Bartok Sonata and just as exciting in performance. It's a shame the piece isn't yet available on recording, but you have to hear it if I'm going to talk about it, so I post its two humorously titled movements here:

(The piece starts very soft and soon gets very loud. I've compressed the dynamics a little for fear computer listening would be totally inadequate.) For Jonathan, the more interesting musical option was not to use other composers' styles in your music, but to make up imaginary styles that had never existed. Thus Notta Sonata contains (to quote what I once wrote about it)Notta First Movement (11:28)

Also Not a First Movement (12:09)

passages [that] sound like Baroque counterpoint on mallet instruments, tonalized fragments of Boulezian serialism, piano horn calls from a Weber opera reworked by Stockhausen with raucously ringing glockenspiels.

Notta Sonata represents a fractured consciousness, an advanced case of stylistic schizophrenia, without sounding like a trip through some composition teacher's record collection. Adding to the rioutous effect is that the music often breaks off abruptly, veers off in a raucous new direction, and then snaps back serenely to where it left off, as though one stretch of tape were spliced into the middle of another. So many passages in it conflate styles that don't fit together, with qualities that no other composer ever thought to fuse in one measure. As far as I know his output, it's Jonathan's masterpiece: a very important (and thoroughly entertaining) work whose historic position and theoretical achievement will inevitably be recognized someday. Why not right away? What are we waiting for? It's been around for 15 years.

Scene 4: This brings us to my own quieter and more modest effort Kierkegaard, Walking. The piece transfers the collage effect of Notta Sonata to the quieter level of Feldmanesque negation; or to put it another way, it pursues Feldmanesque discontinuity on the more pervasive level of Notta Sonata's collage technique. The fragments fused together in the piece are not expansive or complete enough to be distinguished as styles: each is little more than a group of out-of-synch repeating phrases with a certain rhythmic character, based around a harmony or tonality:

The tiles of the mosaic are carefully and intuitively balanced and contrasted as to direction and function: tonal against atonal against polytonal, rhythmically regular against syncopated, additively processed against repeating against through-composed. You could think of each one as a Feldmanesque mini-texture, say, the repetitions of Crippled Symmetry regularized into quarter-notes and 8th-notes. You can listen to a good rehearsal tape of the piece here (15:12), or download a PDF score here.

At the same time, the radical distancing gesture of Feldman's closing disjunctions is normalized into a series of smooth nonsequiturs, like the mountains of Notta Sonata squeezed into a narrow corridor. No passage bears a direct link to its immediate predecessor or successor, but a center, or perhaps multiple centers, can be intuited of which the different passages are manifestations. The most recurrent idea, a series of loops going out of phase with each other, comes back almost as a series of variations on a texture. That image contains within itself a friction between time and timelessness (another Kramer obsession, which he pursued in his fantastic book The Time of Music), since the repetitiveness denies forward progression while the changing combinations imply forward movement. The connection with Kierkegaard is a parallel to the contrast of Either/Or, the time-related aesthetic life versus the sub specie aeternitatis meditations of religiosity; and also the fluid succession of fictional personas that Kierkegaard maintains throughout his written ouput. Taken as a whole, Kierkegaard's total ouevre would be a model of postmodernism, speaking as Victor Emerita one moment, Johannes Climacus at another, and occasionally as Kierkegaard himself.

In being a series of nonsequiturs that relate to each other centrifugally rather than linearly, Kierkegaard, Walking has other, related sources. The centrifugal form - a nonlinear succession of phrases that point to a central idea - calls to mind Nancarrow's Study No. 24, which I've always thought of as his most elegant and most perfectly crafted work. That piece has no motives or harmonic materials of more than local significance, yet derives a powerful unity from the derivations of its alternating A and B sections from a pair of textural ideas, manifesting differently depending on where they occur in the accelerating tempo structure. Another, more obvious model is Erik Satie's exquisite Socrate, also a series of quiet nonsequiturs, seemingly without center.

Of course I don't mean to imply that this is how I consciously arrived at the piece: few of my works have seemed to flow from my subconscious so smoothly, without me "knowing WTF I was doing." But these pieces are all models deeply implanted in me, and which, in retrospect, I recognize as having prepared me for Kierkgaard, Walking. I was very much into the collage idea as a teenager, actually; an ensemble piece of mine from high school (not worth reviving) pits a marching-band version of The Rite of Spring against Liebestraum. But then minimalism came along, and narrow focus was the order of the day. It was when I started writing for Disklavier that collage techniques began to interest me again, because it was so easy to crash fragments into each other without worrying about performance logistics.

In any case, the stylistic nonsequitur has become an option of our current compositional arsenal, and it is clear that it can serve as many different purposes, perhaps, as there are composers to use it:

* the Zen confidence of Socrate

* stylized depiction of rural life (Virgil Thomson)

* bracketing of an otherwise homogenous style (Feldman)

* commentary on the history of music (Bolcom)

* schizophrenia, or perhaps more normal disjunctions in consciousness (Kramer)

* imitation of channel-surfing and other technological intercutting (John Zorn)

* mimicking a Kierkegaardian conversation with its points of stability and abrupt transitions of persona (Kierkegaard, Walking)

There will never be another Rothko Chapel, and that effect can never be achieved the same way again. But no composer today need any longer assume, as he's working on a piece, that the next measure need remain in the same style, or inhabit the same world, as the one he's working on at the moment. It's a curious thing to think about.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog