PostClassic: December 2006 Archives

You will no doubt have seen this before reading me, but John Maxwell Hobbs, in a comment below, calls my attention to Clive Thompson's fascinating interview in the Times with Daniel Levitin, the cognitive scientist who tracks how music gets processed in the brain. The passage that I'll be quoting to my composition students is this:

Observing 13 subjects who listened to classical music while in an M.R.I. machine, the scientists found a cascade of brain-chemical activity. First the music triggered the forebrain, as it analyzed the structure and meaning of the tune. Then the nucleus accumbus and ventral tegmental area activated to release dopamine, a chemical that triggers the brain's sense of reward.

The cerebellum, an area normally associated with physical movement, reacted too, responding to what Dr. Levitin suspected was the brain's predictions of where the song was going to go. As the brain internalizes the tempo, rhythm and emotional peaks of a song, the cerebellum begins reacting every time the song produces tension (that is, subtle deviations from its normal melody or tempo). [Emphasis added]

For years I've harangued my students that every new note creates expectations that must be dealt with - whether fulfilled or contradicted, but at least acknowledged - and now I've got cognitive science to back me up.

My profile of American expatriate composer Linda Catlin Smith is out this week in Chamber Music magazine (probably not online, sorry). A lot of her lovely music is already on PostClassic Radio.

Is it necessary to remark what a tremendous difference between Democrats and Republicans is revealed in reactions to the death of Gerald Ford? No one has anything bad to say about the guy, from either side of the aisle. Democrats, despite one arguable reason to harbor a grudge against him, are happy to concede that the man did virtually no wrong. Had he been a Democrat, the Republicans would be rushing to besmirch his reputation and diminish his significance - as they doubtless will, again, when we lose Jimmy Carter, another generous and honorable president. Remember my prediction.

My "Progress Versus Populism in 20th-Century Music" class became a focus group for trying out recent musical styles. Time and again the students surprised me, never more than by their resistance to the attempt to fuse classical music with pop conventions. They just didn't seem to see it as a worthwhile goal. The way I approached it was, many composers today grow up being trained in more than one genre - playing in a garage band in high school, playing jazz in college, studying classical history and composition - and they're tired of having to compartmentalize. They want to be able to use all their chops in their music, and also to break down this wearying high-art/low-art divide that relegates fun and physicality to one arena and intellectual respectability to the other.

But my students couldn't see it that way. They almost inevitably heard any attempt on the part of a classical composer to integrate pop elements as condescending. The very fact of notating a trap set pattern or a bass guitar riff seemed to locate a composer on the classical side of the divide, and render him guilty of appropriating something that wasn't his. No amount of anecdotal evidence would convince them that these composers (we're talking Mikel Rouse, Nick Didkovsky, Diamanda Galas, Michael Gordon, Mason Bates) had just as much respect for Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix as for Reich and Ligeti. They challenged me to find out what these composers really listened to at home for pleasure, and felt certain it wasn't Metallica.

This biggest reaction came against someone I had considered an easy sell. I'd always thought that Nick Didkovsky's music for his Doctor Nerve ensemble was the most seamless fusion of rock, jazz, and classical ingredients anyone ever pulled off. I started with Nick's piece Plague, which you can click here to listen to. A few students liked the music, but the nay-sayers were vociferous. They thought he had stolen those guitar sounds from heavy metal and was, so to speak, emasculating them by scoring them in a tightly-played, notated arrangement. Some made a big issue about the music being played from sheet music (as I assume it is, it's pretty complex) rather than being memorized - as if playing music from memory is the only way to give it pop authenticity. Some students were really indignant that a bunch of conservatory-educated musicians were stealing these precious pop drum and guitar riffs and sticking them in their sterile, intricately-notated scores.

I don't quite know what to make of this. One thing that occurred to me is, the students have grown up with the commercial boundaries of pop and classical music starkly demarcated by the commercial industry; maybe asking them to rethink their boundaries on a first hearing is too much to ask. What I really can't grasp, though, is how anyone can think that a particular sound can be reserved only for a certain kind of music. What's so holy about an electric guitar pitch bend with distortion that no one outside of a rock group is allowed to use it? It's like the objection, which I've often encountered, that no one should ever use a synthesizer because it sounds like '80s rock. Imagine objecting to someone using a prepared piano because it sounds like John Cage's music of the 1940s! And upon hearing Diamanda's spine-tingling Plague Mass, they dismissed her for using so much reverb, "kind of an '80s sound." (I replied, "Well of course it's an '80s sound, it was made in 1988!") Sometimes I think they've become so attuned to listening to production values that they can no longer perceive the basic content of pitches, rhythms, and text. I reflexively listen to a recording as a document of live music, but they clearly listen to an mp3 as having its own ontological status. But what are we supposed to all do, remaster our recordings every few years to keep up with changing fashions in technology?

I can't tell whether I've got legitimate complaints or whether there's some true pop sensibility that I and the music I love have fallen out of touch with. But the students do confirm, more violently than I might have wished, what I've long suspected: that we new-music composers don't automatically win over new listeners among the pop crowd by using sounds they're used to. It was easier to sell them on music that was just weird in its own way (Feldman, Nancarrow, Ashley's Improvement) than on music that dared tread on sacred pop-music territory. Many good composers feel honestly driven to mix the elements of pop, jazz, and classical music to create new hybrids, and they've gotta do it. The problem has always been, where do you find an audience that wants them mixed, that wants their beloved genre diluted? Not in my classroom, apparently.

I'm getting more and more fed up, for I can see clearly that I was not born into my proper period - [but into] a period I can't accommodate myself to....Erik Satie to his brother, February 4, 1901

I believe we are in a period, and have been for just over two decades, in which masculine archetypes dominate cultural consciousness. The various musics that occupy musical discourse have masculine qualities. "Kickass," hard-grinding, "risk-taking" improvisation has its champions at Signal and Noise and Musicworks magazines, and elsewhere. The orchestra circuit is dominated, not so much by John Adams, as by his legion of imitators, both male and female, who focus violently on the percussion section and make the crescendo of repeated brass chords their trademark. Cults surround the obscurantist music of the priests of the New Complexity, music that never apologizes and never explains. Musically as well as politically, the people seem hungry for leaders, for bullies, for heroes, for those who will lift the onus of responsibility from their shoulders and tell them what to do. Of course, Morton Feldman and Steve Reich, those icons of musical femininity, are highly praised, but nostalgically so, as part of the charming past. Thank goodness no one any longer writes music like that now, right? Or if anyone still does, they should be ignored, if not downright discouraged. That music was pretty, but it's over, and nothing left today but real MAN's music.

Like most of the current music I'm passionately interested in, my music, I think, derives from feminine archetypes. It is communicative, and goes overboard to be clear. Idiosyncrasy is its structural principle. It is always structured, but the structure is deëmphasized, smoothed over, unarticulated by contrast and not allowed to intrude. Pretty is its default mode, pianissimo its favorite dynamic. Its physicality is neither propulsive nor regular, but grounded in a balance of conflicting tempos, making it difficult to figure sometimes what speed to tap your foot to. Neither kinetically nor intellectually compelling, it bows to"emotionally convincing" as its ultimate criterion. Above all it does not hide anything nor intentionally mystify. Back in the '70s, as we were escaping from the brutally masculine archetypes of serialism, that seemed like a good idea. We believed, for awhile, in music not as individual self-aggrandizement but as collective communicativity, in a music that could seduce crossover listeners and bring people together. As Reich said at the time, "I don't know any secrets of structure that can't be heard."

And so, with that sense of being alive at the wrong time, of being totally unfashionable, as utterly irrelevant to the early 21st century as Satie was to the 1900s and Cage to the 1940s, I bring to the public one of my seminal and most unfashionable works. One of the ways I get back into composing after a hiatus is to re-edit some of my earlier music, usually entering it into notation software, as a way of reconnecting with my musical roots: and I've done that now with Baptism, a 1983 work for two flutes, two drums, glockenspiel, and electric organ or harmonium. A pre-Custer attempt to fuse cultures, the piece is based on two hymns from different churches, the Protestant "Jesus Paid It All" and the Apache hymn "Daxiasee Bizra'a" (Son of Our Father.) The music reminds me that I originally felt that my most basic musical impulse, beyond even multitempo and chromatic voice-leading, was the free profusion of melody, not based in any repeitition of motives or themes, but always generated anew from the music's harmonic center.

A PDF of the 24-page score is now available here. The piece was actually published in the '80s by Editions V in Dortmund, Germany, but I've re-edited it for tempos, articulation, and dynamics. Everone comments on the strange, anticlimactic ending, but I'm attached to it, and in 23 years have failed to imagine a better one. Unfortunately, as with all my work from that period, the recording, here, is rather lacking, played on a Casio synthesizer as the only electronic keyboard then available. There were only three or four performances, one in Maine and the rest in Chicago. If you want to complain about the synthesizer, the drones, the homespun quotations (reminiscent of Virgil Thomson's at times), the simple tonality, the lyricism, and even the most peculiar ending from an output bulging with peculiar endings, I anticipate and overrule you. Marking the end of my Eno-influenced ambient period, Baptism was the piece which marked a new phase in my music, faster and marked by a more synchronized tempo complexity. In a certain way it's a naive piece, yet I'm unaccountably fond of it, and wish I knew how to write something like it again.

In 1922, Erik Satie offered a curiously plausible explanation for why it had been easier for him to break away from Wagnerism and create a French style than for his friend Debussy, who had won the Prix de Rome:

When I first met him [Debussy], at the beginning of our liaison, he was full of Mussorgsky and very conscientiously seeking a path that was not easy to find. In this respect, I myself had a great advance over him: no "prizes" from Rome, or any other town, weighed down my steps, since I don't carry any such prizes around on me, or on my back; for I am a man of the type of Adam (from Paradise), who never won any prizes - a lazy sort, no doubt.

- from Robert Orledge's magnificently well-researched and insightful book Satie the Composer (Cambridge, 1990), which I'm reading for a second time and more impressed with than ever.

The squirrels of Columbia County, New York, are incorrigible punks. (Today's post is, as we say, off-topic.) In most respects this is a lovely place to live, but squirrelwise, it's like some Bronx tenement project where the young squirrels grow up without fathers, and fall prey early to gangs of juvenile delinquent squirrels. I've had a squirrel here face off with me two feet away, and look down his nose at me with as little concern as if I were a june bug. My bird feeder still bears a dent in its metal frame where I took a swat at it with a broom to hit the squirrel that had, milliseconds before impact, been staring at me superciliously as it munched away at the birdseed it had no right to. By the time I registered that I had missed, he was on a branch a foot away, drawing on a tiny cigar and snickering with a blasé air. To frighten these creatures is beyond human skill.

A couple of months ago, driving back from North Carolina, I chanced across a garden supply store in Virginia that advertised bird products, and, being in a mood for a break, stopped. Looking through the paraphernalia, my eye was drawn to a running video. On it spun a contraption called the "Yankee Flipper," advertised as the world's first squirrel-proof bird feeder: a large, clear plastic cylinder with a green metal ring at the bottom. Birds could perch on the ring and feed peacefully, but the greater weight of a squirrel, pressing the ring, set off a motor that made the ring spin around, casting the squirrel into the empyrean. I was transfixed: the sight of these squirrels being flung into the air made me laugh until tears ran down my face. You can see the video yourself here, and the manufacturer, a concern called Droll Yankees, has a condensed version here. I instantly resolved to buy one, and only flinched for a moment when informed that the cost was $150. The revenge and humiliation I contemplated would have been cheap at ten times the price.

A couple of months ago, driving back from North Carolina, I chanced across a garden supply store in Virginia that advertised bird products, and, being in a mood for a break, stopped. Looking through the paraphernalia, my eye was drawn to a running video. On it spun a contraption called the "Yankee Flipper," advertised as the world's first squirrel-proof bird feeder: a large, clear plastic cylinder with a green metal ring at the bottom. Birds could perch on the ring and feed peacefully, but the greater weight of a squirrel, pressing the ring, set off a motor that made the ring spin around, casting the squirrel into the empyrean. I was transfixed: the sight of these squirrels being flung into the air made me laugh until tears ran down my face. You can see the video yourself here, and the manufacturer, a concern called Droll Yankees, has a condensed version here. I instantly resolved to buy one, and only flinched for a moment when informed that the cost was $150. The revenge and humiliation I contemplated would have been cheap at ten times the price.

Once home, I hung the Yankee Flipper outside my office window, where I could keep an eye on it. For a month there was no visible activity except legitimate bird feeding. Then one day I heard a momentary whirring sound, and looked out. The Yankee Flipper was swinging, and on the ground was a squirrel squinting up at it with an air of surprise. From that point on, every few hours I would observe a squirrel running up the fencepost parallel to the feeder, staring at it with a look of keen scientific curiosity. After years of getting only smirks of condescension from these scofflaws, it was gratifying to see one absorbed in concentration, truly perplexed and struggling to analyze the mechanics of the dilemma. Finally, a couple of days ago, I had the payoff I'd been waiting for. The squirrel crept down onto the Yankee Flipper from the railing above, lowered himself onto the ring, and clung with all fours as he spun round and round and round for what must have been two dozen revolutions. Losing his grip with one foot after another, he finally spun into the air and crashed on the ground. I laughed until I thought my sides were going to split. The Yankee Flipper had more than paid for itself.

Even as I was laughing, however, a vague disquiet burgeoned in the back of my mind. I was delighted, but not too delighted to notice that as the squirrel was performing his acrobatic feat, his weight made the Yankee Flipper lurch back and forth. With each lurch, a quantity of seed flew out of the seed ports in the cylinder where the birds eat from. Slowly putting two and two together, I looked down, and, sure enough, the squirrel and his fellow hoodlums were busy on the ground harvesting the sunflower seeds, millet, and thistle that had been flung out of the Yankee Flipper. Since then, a repetition of similar feats has confirmed my suspicion: the Fonz of Columbia County squirreldom will voluntarily go for as long a ride as possible, and then he and his cutthroat friends run around feasting on the birdseed. This wasn't supposed to happen. On Droll Yankee's videos, no squirrel ever lasts three rounds, but this little savage can cling for more than thirty.

Admittedly, it doesn't seem like great fun for Da Fonz; upon landing on the ground, he'll sit stunned for a moment or two, and his head makes a repetitive twitching motion. Nevertheless, his patent pride in having outwitted my expensive mechanism clearly outweighs any inconvenience, and I have been forced to concede defeat. The only way to stop him is going to be to get him for tax evasion, like Al Capone. For now, the neighborhood squirrel gang gets its cut of the birdseed, and what I get in return is an occasional entertainment whose hilarity seems to pale with each new instance. My $150 bought me a lesson: no matter how smart you are, you can't transcend a local culture that's been here a lot longer than you have. Or maybe Alpha Squirrel's teaching me something more helpful: when the system's set up to defeat you, you can eventually subvert it if you can just hang on long enough.

My old friend William Hogeland has an op-ed piece in the New York Times today, on the subject of the history of illegal immigration. By "old friend," I mean that Bill and I were freshmen at Oberlin together in 1973, and he's the only person I'm in touch with from those days. A theater major, he played Vladimir in the first production of Waiting for Godot I ever saw.

Bill was an experimental poet, a playwright, and a novelist, and I've read many of his unpublished works that deserve wide circulation. Recently he's reinvented himself with a tautly written history of early American democracy, The Whiskey Rebellion (Scribner). As a detailed story of how this country's wealthy class brought the bulk of the citizenry under its thumb, Bill's storyline makes a timely metaphor for the Bush administration, but he never pushes the analogy - he doesn't need to. If you already thought Alexander Hamilton was the bad guy among America's founders, you'll find his deeds in The Whiskey Rebellion so nefarious that you'll never feel good taking a ten-dollar bill again. The book benefits from a novelist's touch, and achieves a surprise, last-minute-disaster-averted ending worthy of an action film. So keen are Bill's insights that the historians are taking him seriously, and he spends a lot of time lecturing on the country's founders now. Nice to log onto the Times and see his name come up - just as he once opened the Village Voice and was "brought up short" by my name.

Just in time for Christmas Eve, Larry at the Schoenberg Center has posted a Schoenberg music video based on Weihnachtsmusik. Who says there ain't no Santa Claus? Grab a candy cane and gather around the computer screen, kids!

Yesterday I taught my last class of the semester, and do not teach another one until February of 2008. My sabbatical has begun, and the English language affords no sweeter word. The next 13 months will consist of only composing, writing, traveling, and, of course, blogging. I slept last night as I haven't in many months. If you are the kind of musician who tends to envy other musicians, you may envy me now. If you know of any other kind of musician, I'd love to hear about it. I'll let you know when you can go back to regarding my life with bemused schadenfreude. The day will come.

My students, most of whom I am devoted to and vice versa, have trouble understanding why I am so eager to distance myself from them. I tell them, truthfully, that teaching them is a pleasure, and that the relief does not derive from extracting myself from that cheerful, mutually fertile interaction. I try to phrase delicately that certain tensions arise between a professor and his fellow faculty that grow to consume one's idle thoughts, and that removal from the sources of such tension goes a long way toward restoring mental health. The looking-glass world that is the administration's view of the faculty is also a surreal environment, and the daily cognitive dissonance of evaluations, reports, meetings conducted in such surreality impinges on one's sense of the truth.

Those are the excuses I can give them. But how can I also tell them that, as much as I love teaching them theory, immersion in theory is suffocating for an artist? That every week as I exhort them to avoid unresolved 6-4 chords and false relations in their music, I am chomping at the bit to go home and write my own music filled with unresolved 6-4's and false relations? That the daily construction of musical normalcy with which I regale them, in order to give them a framework to rebel against later, interferes with the looking-glass world of my own music, in which everything is as upside-down as possible? That the dead composers I push on them are unwelcome intruders into my own creative solitude? That the composer who teaches is forced into a dishonest double life, an insecure, nose-thumbing spinner of dreams masquerading as a credentialed authority, and that one must occasionally come up for air and live honestly for a time, or die as an artist?

I have written at length on the dissatisfactions of the academic life, which strikes me as no better or worse than any other for an artist - or rather, both much better and much worse than others, in equal amounts. As Virgil Thomson famously chronicled, every method of making money has its dangers for an artist, including inherited wealth. I imagine that if some demiurge saddled me with a Pulitzer Prize and plopped me in front of the Cleveland Symphony as their composer-in-residence, I would find that environment as damagingly surreal as the one I just escaped from, as full of inflexible expectations and uncomfortable social obligations. I am apparently not very good at dealing with authority figures, or at least so the authority figures I work for have been telling me. Better that I should deal with them from a perhaps marginalized but still tenured and thus stable position. If I lived on commissions and the Cleveland Orchestra board of directors were my authority figures, I would doubtless soon find myself tossed out on my ass and commissionless. Onerous as are its excesses, this life is probably the extant artistic model that my intransigent personality can best accommodate itself to. There were drawbacks to being a critic, too - though, to tell you the truth, I no longer remember what they were.

Somehow in its otherwise so flawed wisdom academia recognizes that it cannot crush the spirit out of a man eight months a year forever and expect that man to retain his usefulness, and so it offers him a free semester now and then to "develop his career." That's a euphemism for returning to reality and remembering why you embarked on this particular course in life in the first place, which I joyously begin doing today.

I find it difficult to credit this, since my blog is so peripheral to my activities in general - merely an adjunct to my professional writing, which is already an adjunct to my teaching, which is itself something I do to support my composing - but this blog entry seems to indicate that Postclassic is number 5 among the top classical music blogs. Geez, Louise, what an easy profession. Frankly, I think listing me one notch above Sandow is bogus. He gets a lot more traffic than I do. (Besides, this is a POST-classical blog. How about a listing of the top postclassical blogs, huh? Who'd be number one then, Alex Ross?)

While I've got my blog formatting page stoked up, would you like a recommendation on a Christmas gift for music lovers? Albert Glinsky's Theremin: Ether Music & Espionage is the most exciting music biography I've ever read. There are a lot of good biographies, but very few subjects this astounding: Leon Theremin was not only a music-technology genius, but a KGB agent involved in some strange stuff, who disappeared and was presumed dead for decades as he was actually implicated in international espionage. Glinsky's page-turner reads like a detective story, and he fills in gaps in his subject's mysterious life with the sometimes hilarious pop history of the theremin. Anyone remotely interested in new music should have this fascinating, effortless read.

While I've got my blog formatting page stoked up, would you like a recommendation on a Christmas gift for music lovers? Albert Glinsky's Theremin: Ether Music & Espionage is the most exciting music biography I've ever read. There are a lot of good biographies, but very few subjects this astounding: Leon Theremin was not only a music-technology genius, but a KGB agent involved in some strange stuff, who disappeared and was presumed dead for decades as he was actually implicated in international espionage. Glinsky's page-turner reads like a detective story, and he fills in gaps in his subject's mysterious life with the sometimes hilarious pop history of the theremin. Anyone remotely interested in new music should have this fascinating, effortless read.

For musicological purposes, if nothing else, I should write a few words about the experience of performing Julius Eastman's Gay Guerrilla with electric guitars. This work, along with its companion pieces Evil Nigger and Crazy Nigger, are ostensibly written for multiples of any instrument. At Northwestern in January of 1980, and at New Music America in Minneapolis in July of that year, Julius performed the piece with four pianos. [UPDATE: Mary Jane Leach adds that the Kitchen toured the piece in Europe that year.] Aside from those and our electric guitar rendition of December 14, I'm unaware of any other performances; I'd love getting information if anyone knows about any. I announced Thursday that that evening's performance might well have been the first since 1980.

With its long streams of reiterated notes, there are only a few instruments Gay Guerrilla could conceivably be played on. A Gay Guerrilla for oboes is unthinkable (one shudders to imagine). Mallet percussion is a possibility. Strings are too, though the notated pitches cover something like four octaves, so a full string ensemble would seem more appropriate than multiple violins. Pitches are supposedly transferable to any octave, but when Julius puts certain figures in notes below the bass clef, it's difficult to take that latitude too literally. The piece starts off with one line, and alternately expands and contracts up to nine; with four pianists, each obviously played more than one line. Luckily, we had nine guitarists, and two of those played bass guitars, which seemed the right percentage, though in some passages a third bass would have been welcome. In the piano version, the pianists would dot out the repeated pitches with the pedal held down. On guitars, the plucking of each note would damp the last, so we had to play a little more slowly to get a good resonance. Our first, too-quick runthrough sounded pretty pinched.

The original ms., dated September 1979, which we started out playing from a Xerox of, is sometimes cryptic. A real Downtown score, it needed not only to be interpreted, but deciphered. (Mary Jane Leach has up the opening pages of a similar score, Evil Nigger.) Each line contains figures to be repeated within a certain span of time, notated at beginning and end in minutes and seconds: often these figures are simply steady quarter- or 8th-notes, or else quarter-notes alternating or interspersed with 8th-note pairs. Inconsistency is rife. Sometimes bass clef lines are at the top of the system, above treble clef lines. The quoted tune "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" is notated with a bass clef, though the notes are clearly intended for treble clef (otherwise the tune would be D D D A# B# C# instead of B B B F# G# A#). Enigmatic notations appear. The students enjoyed an inscription that read "THE LESSING IS MIRACLE," and the music did indeed thin out at that point. Since the Xeroxes were 11"x17" with lots of unused space, I finally renotated the entire piece into Sibelius, and extracted individual parts, cutting 22 page turns (of 11"x17" pages) down to 5 (of 8"x11"). This involved considerable "orchestration" of the work, deciding which pitches to double when the number of lines would vacillate widely with no seeming concomitant change of dynamics. I'm afraid I don't remember how the doublings were decided 26 years ago. I may have to think of my version as just an "arrangement." Even with the inconveniences of the ms., though, students agreed that something was lost when we switched to the nicely printed Sibelius version, and the spirit of the piece became a little harder to capture.

The original ms., dated September 1979, which we started out playing from a Xerox of, is sometimes cryptic. A real Downtown score, it needed not only to be interpreted, but deciphered. (Mary Jane Leach has up the opening pages of a similar score, Evil Nigger.) Each line contains figures to be repeated within a certain span of time, notated at beginning and end in minutes and seconds: often these figures are simply steady quarter- or 8th-notes, or else quarter-notes alternating or interspersed with 8th-note pairs. Inconsistency is rife. Sometimes bass clef lines are at the top of the system, above treble clef lines. The quoted tune "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" is notated with a bass clef, though the notes are clearly intended for treble clef (otherwise the tune would be D D D A# B# C# instead of B B B F# G# A#). Enigmatic notations appear. The students enjoyed an inscription that read "THE LESSING IS MIRACLE," and the music did indeed thin out at that point. Since the Xeroxes were 11"x17" with lots of unused space, I finally renotated the entire piece into Sibelius, and extracted individual parts, cutting 22 page turns (of 11"x17" pages) down to 5 (of 8"x11"). This involved considerable "orchestration" of the work, deciding which pitches to double when the number of lines would vacillate widely with no seeming concomitant change of dynamics. I'm afraid I don't remember how the doublings were decided 26 years ago. I may have to think of my version as just an "arrangement." Even with the inconveniences of the ms., though, students agreed that something was lost when we switched to the nicely printed Sibelius version, and the spirit of the piece became a little harder to capture.

At the NMA performance I had served as timekeeper by holding up pieces of paper that showed the onset time of each new system. Thursday night we used a computer-screen stopwatch instead, which was a convenient and much more elegant solution, with fewer visual cues to the audience as to what the mechanism was. Being able to anticipate the beginning point of each new line, the ensemble could mysteriously turn on a dime.

The performance was stunning, much louder than the piano version of course, and not so much sadly stern as menacing at times, almost like a Branca symphony - though without any urging from me the group took a restrained approach to volume. I kept thinking of Bruckner too (one of Branca's favorite composers), because of all the reiterative sonorities cycling through slow harmonic changes. There are passages in which the harmonies are dense and dissonant, and the loud guitars fused into a sound more than the sum of its parts; some reported audio illusions, thinking they heard voices. And the piece seemed to be virtually a universal favorite on the concert. My nine "gay gorillas," as I came to call them, worked hard and were dedicated to the piece, and deserve to be cited for participating in this historic occasion: Brian Baumbusch, Willy Berliner, Bernard Gann, Kenji Garland, Liam Hofmann, Narayan Khalsa, Anthony Kingsley, Jonathan Nocera, and Ezekiel Virant. Maybe they'll all be famous musicians themselves someday. If so I hope they'll notate a little more clearly than Julius did.

Me with my gorillas: Aaron Wister (standing at left), JP Nocera, Ben Richter, Brian Baumbusch. Photo by Anne Garland, Kenji's mother and wife of brilliant avant-garde songwriter David Garland.

I've learned too many things from my students in the past two weeks to get them all in one blog entry. It'll take three at least.

Our three-and-a-half-hour Open Instrumentation Ensemble concert last night went splendidly. We played Glass's Music in Fifths, Riley's In C, Samuel Vriezen's The Weather Riots, Rhys Chatham's Guitar Trio, Rzewski's Attica, and an electric guitar version of Julius Eastman's Gay Guerrilla, plus three works written by students in the ensemble. I was truly dumbfounded by the massive student enthusiasm for this music - as though they'd been looking all their lives for music like this, and weren't sure it existed. They are determined to continue the ensemble next semester in my absence. And I'm trying to figure out what needs it fulfilled for them.

For one thing, pieces like these allow for a wide range of proficiencies. We had, in this ensemble, both senior instrumentalists of considerable virtuosity and freshmen guitarists who could hardly read music and had never played notated music in an ensemble before. Both were challenged, neither got bored. Music in Fifths, with its interminably expanding patterns of 8th-notes on F G Ab Bb C, is difficult to play, but it is not particularly more difficult for beginners than it is for the more experienced. Its difficulties have to do with cognition, concentration, and endurance, not instrumental ability or musical insight. The inexperienced had more trouble at first getting Riley's 53 melodies in their heads, but once that's done, the challenges are pretty much the same for everyone.

More than that, though, I think this minimalist, process-based repertoire has a kind of performance density that younger musicians enjoy. Classical music is all about enslaving yourself to an inexorable continuity drawn out on the page. Jazz is certainly freer in a way, and Bard has a thriving jazz program - probably the healthiest part of our department at the moment - but there are certain students who find the jazz regimen too limiting. Our jazz students learn the bebop language forwards and backwards, and play Charlie Parker fluently before going into anything more experimental. It's rigorous. Classical music and jazz both impose on the young musician a tremendous discipline undertaken for the goal of playing with consummate expertise a repertoire that - however sad to say - may ultimately seem a little old-fashioned, not terribly hip to most of their friends. The road is long and torturous, the rewards far away and, in social and economic terms, arguably dubious.

But minimalist music? Easier to master, and the result of a training more personal than professional. Highly developed expertise isn't entirely an asset; I've heard student performances of In C that were way better than the one the New York Philharmonic gave at Merkin Hall a few years ago. More importantly, the performance mode is not so fraught with anxiety. Within In C and Attica, there's room for individual performance decisions made on the spot. Miss a pattern in Music in Fifths? Drop out for a measure, and then plunge in again - not only does no one care, it adds variety to the texture. (We had one excessive moment in which we lost the entire guitar section, but the closing repetitions were dynamite.) The discipline is more quickly achieved, creativity encouraged, mistakes far less penalized.

And the rewards? In the short run, far higher, for the music is both exotic enough to impress friends with its hypnotic strangeness and groove-oriented enough to delight them. It's music you can perform with the comfortable familiarity and leeway of pop, but with more intellectual heft and formal interest. The three student pieces were all based on In C-like techniques, yet achieved quite different textures and forms. In fact, it's really a perfect performance repertoire for college-age musicians: you can get good at it fast, a little effort will make you really good, mistakes are rarely an issue, you can compose it without sweating over every note, little changes in rehearsal can make a big difference, and it's mesmerizing to listen to. The reward/discipline ratio is through the roof.

OK, then, why do most of the classic pieces from this genre date from the 1960s and '70s? I located a few scores from the 1980s, like Barbara Benary's Sun on Snow, but they were more elaborate, and would have required more rehearsal time than we had. We composers mostly all retreated from this kind of aptly-named "new music" in the 1980s. Even I gave up writing freer, looser music like my Oil Man and Long Night of 1981 to return to more linear, strictly notated works like Baptism of 1983. In my own case, I always think of Feldman's statement about why he abandoned graphic notation: "If the means were to be imprecise, the results must be terribly clear." Leaving certain musical details to chance and performer discretion didn't gratify my sense of composer vanity: I wanted to prove I could get every nuance in place and make it beautiful. Performances of my freer music were sometimes great, sometimes lousy, and I didn't feel I had enough control. I don't think that's particularly true of Music in Fifths, however. I think, rather, that I hadn't quite found processes that could be guaranteed to work well in performance.

And I regret that. The '60s and '70s were an era of tremendous liberalism, and I think that all that minimalist music (to use an imprecise term for the body of process-oriented works for variable ensembles) was an expression of our political inclinations. We were disenchanted with expertise. The experts all seemed to be wrong. We were inclusive. We were writing music for Everyman. We (or our immediate predecessors) came up with a music that made newcomers feel comfortable playing it. Soured on elitist self-aggrandizement, we were in a mood to be generous to performers and listeners both. The music was accessible, striking, attractive, rhythmic. It gave, in Steve Reich's words, "everyone within earshot a feeling of ecstasy." And part of that ecstasy surely came from the sense of freedom and personal responsibility of players who were being allowed to make their own decisions without undue fear of mistakes.

So why didn't we continue? Why didn't this new genre, with so much to offer, become a new tradition? Times changed. The credentialism of the 1980s, and the renewed competition for jobs, brought back an elitist sense of professionalism. Some of us became successful enough that virtuosos were interested in performing our music, so goodbye Everyman. But I remain convinced that there were worthwhile political convictions expressed in the very cellular structure of that music, and the continuing student (and public) enthusiasm for it seems evidence of that. I may write a piece for the students' ensemble myself, and I'm going to try to see if I can't return somewhat to my liberal, '70s, open-instrumentation, process-oriented roots and see if it's possible to channel that populist energy in a new century.

"Silent Night" begins with the notes G A G E. "Lo, How a Rose E'er Blooming" starts with the same pitches, G G G A G G E. Arnold Schoenberg was delighted by this coincidence, and in 1921 wrote a little work for piano, string trio, and harmonium, in which one tune morphs into the other. Called Weihnachtsmusik, it's absolutely charming - and not one new-music fan in thirty that I talk to has ever heard of it. In fact, it's the one Schoenberg piece about which I feel most affectionate, and I almost have to assume that Schoenberg's fans hide it because they're ashamed that he wrote something so damn lovely. I'm adding it to Postclassic Radio, but I also put it here on my website, as a Christmas gift to you for reading me. The recording is an old Decca vinyl record by David Atherton and the London Sinfonietta, and I've never seen another. It was well after this, by the way, that Schoenberg asserted, "There's a lot of great music left to be written in C Major."

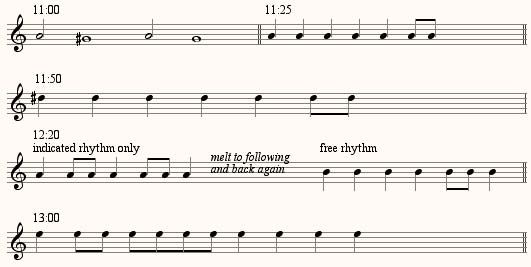

This Saturday night, December 16, at 7:00 PM at Bard College's Bard Hall, my son Bernard Gann will present a concert of his music. Much of it will be by his rock trio, Architeuthis. A piano piece will be played by, coincidentally, student Ming Gan. And a new work called Two Organs will be performed by myself and Joan Tower on electric keyboards. Joan and I have never performed together. It is highly unlikely that we will ever perform together again - I'm not much of a performer, except possibly of my own music, and Joan has retired from anything but conducting. I half think Bern wrote the piece to get us onstage together. So if it ever occured to you that it would be fun to see Kyle Gann and Joan Tower play a duet, this is, in all probability, your one shot. A cofounder of the Da Capo ensemble, Joan is, of course, an incredibly more experienced pianist than I am, and it's fun playing with her - she's so good at signaling her intentions, and completely easy to follow. The piece itself is kind of a moment-form postminimalist piece, Glass crossed with Stravinsky, and here and there a Terry Riley echo, enlivened by some totalist rhythmic complications (pictured) that have had me tearing my hair out. Later I'll put up some Architeuthis music on my web site, because I'd be curious about your opinions.

Tonight, of course, my Open Instrumentation ensemble performs at Bard Hall from 7:30 to 10:30. The description here will refresh your memory.

The ever-vigilant Jon Szanto draws my attention to an admirably insightful summing-up of James Tenney's output by Mark Swed, in the form of an LA Times review of the recent Tenney memorial concert. Wish I'd been there - it sounds splendid.

American expatriate composer Nancy van de Vate (or maybe we should call her "Austrian composer," we can argue about that later) kindly informs me that pianist Iris Gerber, famous for her toy piano work, is giving a concert this Friday at 7 at the Alte Schmiede in Vienna, titled: "Down Town New York: Kyle Gann und Tom Johnson, die Komponisten-Kritiker der Zeitschrift Village Voice und ihr Schaffen." I don't know which of my Schaffen she's playing, but I'll list a program if I get it. She would have needed to include Carman Moore and Greg Sandow, though, to get all of the Voice's composer-critics.

YouTube offers an incredible Oscar Peterson performance. Make sure you go past 2:44, when he goes crazy. Peterson received an honorary doctorate at Northwestern the year I got my regular doctorate there (1983), so I was once on a stage with him. But not playing.

Compliments are something I'm inured to, and I'm well aware that everyone in every public field receives them for reasons that have nothing to do with quality. But I am particularly touched by Time Out's mention of my new book Music Downtown. In an article reviewing New York's critics they don't include me, of course, since I haven't written in the city since last December. But they do include my book in a list of anthologies of criticism, with the very kind comment:

One of the cruelest cuts of the ongoing reorganization at the Voice is the loss of Kyle Gann, the paper's unparalleled chronicler of contemporary music and the downtown scene in particular. Like [Virgil] Thomson, Gann is a composer; his best pieces are informed by a sense of being in the trenches that no bystander could hope to achieve. As a memento of New York music in the '80s and '90s, this anthology is indispensable.

What a gratifying notice.

I just now got out of a three-and-a-half-hour rehearsal for the concert I'm presenting next week, of my Open Instrumentation Ensemble at Bard. December 14 at 7:30 in Bard Hall, we'll be presenting the following marathon program:

Philip Glass: Music in Fifths

Willy Berliner: Persistence of Vision*

Samuel Vriezen: The Weather Riots

Frederic Rzewski: Attica

Brian Baumbusch: Cyclical Counterpoint with Sangse*

Rzewski: Les Moutons de Panurge

Julius Eastman: Gay Guerrilla

Jonathan Nocera: Blues for Julius Eastman*

Rhys Chatham: Guitar Trio

Terry Riley: In C

The pieces with asterisks are by Bard students, written for the ensemble. The historical highlight is Eastman's Gay Guerrilla, which is scored for multiples of any instrument; he always performed it with pianos, and we're giving what is, as far as I know, the world premiere of an electric guitar version. The students love the piece (you'll note one of them wrote a piece dedicated to Julius), and they did a dynamite job of playing it tonight. When they started echoing the hymn "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" back and forth, which Julius subverted as a gay manifesto, it was a goosebump moment, and I suddenly felt his sardonic spirit fill the room. To be an audience of one at such a performance (since the other players had gone home) was a humbling privilege. I hadn't directed an ensemble since 1976 - the year I gave the Dallas premieres of some pieces by Reich, Glass, and Riley at Carruth Auditorium at SMU - and I have little experience to remind me how fulfilling it is.

I'm also very proud that these students will graduate free from the academic fallacy that a score must be a complete and detailed reflection of a predetermined sonic image; that they'll always know that compelling music can be made with repeat signs, gradual processes, and considerable performer latitude, and that it can be a real blast to try out the same music with a variety of different instrumentations, and with diverse dynamic shadings. The student pieces allow lots of performer decisions, and the composers have had fun experimenting with different rules and combinations in rehearsal - so utterly different from the classical experience in which they're expected to notate every nuance for professional players who will execute their notation with computer-like precision. The students' enthusiasm and dedication have astonished me, and made me proud that I have this important Downtown repertoire, and attitude, to pass on to them.

We're having a pretty tedious reversion war over at Wikipedia vis-a-vis the Nancarrow article. I refer to Nancarrow as an American composer who moved to Mexico. I would be happy to call him an "American-born and -trained composer who took Mexican citizenship." But a couple of guys, including Conlon's late-life assistant Carlos Sandoval, insist that he must be referred to as a "Mexican composer." I find this misleading, cognitively dissonant. Nancarrow did take Mexican citizenship in 1955, but he had few friends among Mexican composers, who were more oriented toward European than American music. I once asked him if his music had been in any way influenced by Mexican music or culture, and his characteristically laconic response was a flat "no." Conlon spent his life working out ideas he had found in Cowell's New Musical Resources, and he was championed and lionized by American composers (Carter, Cage, Garland, Amirkhanian, Reynolds, Mumma) long before the Europeans discovered him; his tiny influence on Mexican music has been mostly posthumous (one might cite the Microritmia duo).

This is a trivial fight, surely. But can you feel comfortable talking about "Alfred Hitchcock, American film director"? "Isang Yun, German composer"? "T.S. Eliot, British poet"? "Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg, American composers"? Is an artist's country of upbringing and training, the crucible in which his artistic vision was formed, to be so lightly cast aside because, for whatever political or personal reasons, he later in life had to live somewhere else?

I have noted here before that I am a fairly notorious introvert. There are periods, such as the present, in which very little in the outer world catches my attention. However, I am not, in person, much given to talking about myself unless asked, and I do, for the record, feel some pangs of conscience when my blog ends up being mostly about myself. So, sorry to be so self-obsessed lately, but I might as well alert you to the fact that Jean Churchill, professor of dance at Bard College, has choreographed two of my Disklavier pieces for faculty dancer Maria Simpson, who will perform to them this weekend, December 8, 9, and 10 at the Fisher Center. Also, December 12 at 6:30, I will give a reading from my book Music Downtown, at Bard Hall on campus.

And while I'm at it, I might as well divulge the rest of my future plans. I have received a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to complete my book Music After Minimalism, an analytical/philosophical study of postminimalist music, which means that I will indeed be able to extend my sabbatical an extra semester and be blissfully absent from Bard for the entire year of 2007. I also have the following commissions to work on:

- a piano concerto for pianist Geoffrey Madge and the Orkest de Volharding in Amsterdam, to be premiered next October 31;

- a solo cello piece for Frances-Marie Uitti, for her two-bow technique;

- a quartet for the Seattle Chamber Players to be premiered in January, 2008;

- three more movements of The Planets for Philadelphia's Relache ensemble, which they will record in summer of 2008;

- an electric guitar quartet for Tim Brady's "Voyages" festival in Montreal, for a February 2008 premiere;

- a conventional cello work for André Emilianoff of the Da Capo ensemble.

In January I am recording a new disc for New Albion; February 19 to March 11 I am composer-in-residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts; March 10 the Dessoff Choir will premiere my new work My father moved through dooms of love at Merkin Hall; and May 15-20 five of my Disklavier works will be choregraphed by Mark Morris at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. This is, at long last, my year of uninterrupted composing and writing, and bloody sick and tired of hearing about it you'll soon enough be. But with luck, once the semester's over I'll have some disposable attention to turn to the outer world, and will also find something more fascinating to blog about than myself.

A student complained that my microtonal music-theater piece Custer and Sitting Bull is currently (if temporarily) out of print, and that it's not available on my MP3 web page either. It's a reasonable complaint, so I've fixed that. The whole thing can now be heard here, where it will remain at least until Monroe Street brings the CD back out.

UPDATE: Well, heck, in response to a subsequent request, I can put the links right here, if you want:

Custer: "If I Were an Indian..." (8:42)

Sitting Bull: "Do You Know Who I Am?" (8:17)

Sun Dance / Battle of the Greasy-Grass River (7:59)

Custer's Ghost to Sitting Bull (10:04)

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog