PostClassic: February 2006 Archives

At 8:00 this Friday, March 3, at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Santa Fe, pianist Sarah Cahill will perform a concert for Santa Fe New Music that includes my own Time Does Not Exist. The devoutly American experimentalist program of mostly 21st-century music is as follows:

At 8:00 this Friday, March 3, at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Santa Fe, pianist Sarah Cahill will perform a concert for Santa Fe New Music that includes my own Time Does Not Exist. The devoutly American experimentalist program of mostly 21st-century music is as follows:

Kyle Gann: Time Does Not Exist (2000)

Bunita Marcus: Julia (1989)

Peter Garland: Walk in Beauty (1989)

Johanna Beyer: selections from Dissonant Counterpoint (1934)

Guy Klucevsek: Don't Let the Boogie Man Get You (2005)

Andrea Morricone: Studio I (2005)

Ruth Crawford: selections from Preludes (1925-1928)

Annea Lockwood: RCSC (2001)

Pauline Oliveros: Quintuplets Playpen (2001)

Maggi Payne: Holding Pattern (2001)

And you can find out more here. All of these composers are ones that SFNM director John Kennedy has done a lot for in the past - for instance, he gave the first one-woman show for the almost-forgotten pioneer Johanna Beyer. (If you're wondering, Andrea Morricone is the son of the film composer.) The concert is worth it for Bunita Marcus's Julia alone, one of the most beautiful pieces in the recent repertoire.

The next day at 2 PM at the same place, Sarah is playing a concert of pieces about childhood, including works by Debussy, Schumann, Rzewski, and Family Piano by Kennedy himself. Kennedy's One Body has been playing lately on Postclassic Radio. You can get more info about these concerts by calling Santa Fe New Music at 505-474-6601.

Wish I were there. I love Santa Fe. There's a great cigar store just west from the southwest corner of the town square, and across the street from it an incredible store for Spanish-language books that also has a huge stock of scores of works by Mexican and Central American composers. It's heaven. Maybe I'll retire there, and time really won't exist.

The February theme of Postclassic Radio was "doldrums," or perhaps "passivity," since I'd been too involved in other matters to add any tracks in several weeks. But I've made up for that today with more than 35 percent new content, including works by David Lang (Slow Movement), improvising violinist Kaffe Matthews, Ben Johnston's Ninth String Quartet from the new Kepler Quartet recording, Sarah Cahill playing Pondok from the new Evan Ziporyn album, a smattering of works by Barbara Benary, Janice Giteck's classic Breathing Songs from a Turning Sky, several songs from Amy Kohn's new disc I'm in Crinoline, Sub Rosa by Gavin Bryars, Circa from Belinda Reynolds's brand new CD, Kilter by Peter Hess of Anti-Social Music, some more of Mikel Rouse's Love at Twenty (his best new album in years), and Compassion, a rare 63-minute piece for violin and piano by the inimitable Chris Newman. Take note that the textures of Love at Twenty are largely composed of sampled notes from Cage's prepared piano for Sonatas and Interludes. No official composer-of-the-month for March, but I'm pushing Benary these days, who has few recordings out, and I've obtained some CDRs. Enjoy!

Live 365 is now giving me error messages if I fail to provide "e-commerce info," such as label and copyright. It's all about selling things at Live 365, but not at Postclassic Radio.

I got to see composer George Tsontakis onstage tonight - as Otto Frank, the father, in The Diary of Anne Frank. George, who's always telling me how tired he is of composing these piano concertos and violin concertos he keeps getting commissions for, has taken up acting as a sideline. (I noticed from his bio in the program that he even studied acting in college.) Last year I missed him in Barefoot in the Park, so I made sure I got out to the Shandaken Theatrical Society Playhouse in Phoenicia, NY, to see him bring a certain benevolent gravity to his role as the wise father who's always calming everything over among the eight Jews hiding from the Nazis in a Dutch attic. As the only family member to survive, he even had the emotional closing monologue. He acquitted himself well... though I have to say I still think he composes a little better than he acts, so I hope he won't quit the day job.

Stephen Greenblatt’s Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare is entertaining and insightful throughout, but when it reaches the year 1600 and Hamlet, it becomes brilliant. Greenblatt attributes the transcendence of Shakespeare’s late tragedies to a technical device that he labels excision of motive. In each case, Shakespeare made his story less logical than his historical sources by removing an obvious motivation. For instance, in the original Hamlet saga, Hamlet’s uncle kills Hamlet’s father the king in plain sight, so that there is no secret as to who the murderer was. Young Hamlet feigns madness for a manifest practical reason, so that his uncle will think he is not dangerous; otherwise, the uncle would have to kill Hamlet for fear that he would eventually avenge his father’s death. Making the murder a secret revealed only by the ghost, Shakespeare removes the rationale for feigning madness, relocating it in Hamlet’s own psychology.

By excising the rationale for Hamlet’s madness, Shakespeare made it the central focus of the entire tragedy. The play’s key moment of psychological revelation - the moment that virtually everyone remembers - is not the hero’s plotting of revenge, not even his repeated, passionate self-reproach for inaction, but rather his contemplation of suicide: “To be or not to be, that is the question.” [p. 307]

Likewise, in the original sources for King Lear, the king poses a test to find which of his daughters loves him most because he is about to divide his kingdom proportionally. But at the opening of Shakespeare’s version, Lear has already divided his kingdom in three equal parts to give to his daughters: thus there is no rationale for the love-test, which seems like an arbitrary neurosis on his part. Shakespeare made his plays more powerful, Greenblatt argues, because the mainspring for the characters’ actions is no longer the logic of the situation, but something gnawing at them from the inside, which we and the dialogue must now focus on to figure out. It’s a compelling reminder that a work of art draws its highest power not from making rational sense, but from clearly-delineated contradictions whose non-sense draws us into the work.

Aside from printing "Caution: Contents may be hot" on a therma-foam coffee cup, I think the silliest disclaimer in common use is the one that seems to precede every compliment paid to a critic, viz.: "Although I don't always agree with him, Kyle Gann is an OK critic," etc. I thought it was understood that only Rush Limbaugh has Dittoheads. It makes me imagine distancing myself from all kinds of analogous syllogisms:

"Even though I agree with his every utterance, I find Alex Ross a lousy critic..."

"Although I am not her identical twin, and, in fact, look nothing like her, I consider Angelina Jolie very pretty..."

"Despite the odd coincidence that he and I are both featherless bipeds with hair and opposable thumbs, I consider George W. Bush a malevolent moron..."

You spend your life analyzing, explaining, trying to bring a little clarity to your corner of the chaos, and you get measured against a checklist of someone's opinions.

There's a lovely article on New Music Box today by Corey Dargel, about the difference between the traditional art song or lieder of the classical music world and the new "artsongwriters" who write and sing their own lyrics - just like pop artists, but with a whole different structural sensibility. One of the prime practitioners of this 25-year-old art form, Dargel knows whereof he speaks.

As an addendum to my post on 4-against-5 rhythms, I should mention Paul Epstein’s 1998 harpsichord piece, 57:4/5/7. I think of Paul as a postminimalist rather than a totalist, but he goes the totalists one better: the piece is based on interfering periodicities of 4-against-5-against-7. (I tend to call pieces postminimalist when based on a steady beat unit throughout, and totalist when conflicting tempos are implied. For the record, I don’t give a damn whether anyone joins me in this.) I don’t know a mnemonic device for figuring out 4:5:7 - if you’re dealing with durations of 4, 5, and 7 16th-notes, you’d need 70 syllables to fill out the 140 16ths it would take those rhythms to come back in phase, and you’d need a mnemonic to help you remember the mnemonic, and probably another mnemonic to help you remember that. (If you’re simply dividing a measure into 4, 5, and 7 simultaneously, layering tempos rather than durations, you’d only need 14 syllables, but how to space them would be a knotty problem.)

But you can see Paul’s compositional use clearly here at the beginning of the piece, the three lines moving in tempos of 4, 5, and 7 16th-notes, switching register at the points where the 4:5's, 4:7's, and 5:7's coincide:

Since the piece is for amplified harpsichord, there are no dynamics indicated, though in every other respect the notation is meticulous. And before influencing your perception of the piece by reading how it works, you can hear the ten-minute piece here, performed by harpsichordist Joyce Lindorff.

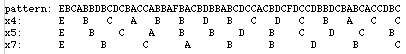

This is a work of art as abstract as Mondrian’s Composition No. 2, as Milton Babbitt’s Three Compositions for Piano or Webern’s Op. 24 Concerto. It is music about the logic of music - but its logic is perhaps easier to process audibly than Babbitt’s or Webern’s, and more playful. His interest sparked decades ago by Steve Reich’s early music and the logical processes of Tom Johnson, Paul Epstein has long nurtured an interest in attractive surfaces generated by tight, self-replicating melodies. 57:4/5/7 is spun from a 57-note series structured in such as way as to replicate itself every 4, 5, and 7 notes, as can be seen in this breakdown whose lower three lines correspond to the opening measures above:

However, Paul’s music is never as mechanical as this correspondence suggests. Like many of his pieces, 57:4/5/7 is kind of a theme and variations on a logical concept. As you’ve heard or will hear, it changes key, it goes through a series of different textures, sprouts melodies, and its 16th-note momentum speeds up to various densities. Rarely does Paul simply set a process in motion and let it run. I sometimes call him “the postminimalist Babbitt” because of the ingenuity he expends twisting these logical constructs into an obvious-sounding but elusive series of processes. (And contrary to what you may assume, Babbitt is the composer of many pieces I have long been fond of.)

What I get from Paul’s music is a pleasurable but slightly exasperating feeling that I could figure out what the music’s doing if I could just listen a little harder. Motives repeat, tunes emerge, voices echo in canon, and I keep thinking that the piece will resolve into something obvious any minute now. This is a common experience for postminimalist music, which, more than totalism, has often become a strategy for setting up cognitive dissonances. In its most intricate form (of which Esptein is the extreme and William Duckworth another strong example), it tends to create structures that sound consistent and logical, but in such a way that the ear can’t quite tease out where the logic comes from.

It seems to me that postminimalism, and to a lesser extent totalism, have suffered in the public ear from having flourished at a time when formalism had acquired a sour reputation, following the long-awaited demise of 12-tone music. After I wrote the article “Downtown Beats for the 1990s” that sparked recognition of totalism, one of my Midtownish composer friends (Scott Wheeler) remarked with surprise, edged with disapproval, that “the Downtowners seemed to pick up where the Darmstadt composers had left off.” It’s true that postminimalism and totalism were united by the exploration of technical devices, as a way of creating a new musical language. Outsiders to the style have not had much patience for this particular aesthetic goal over the last 25 years. Even though serialism’s strictly formalist period was the 1950s, and it had evolved into something else by the 1970s, it created an understandable public perception that to “merely” play with formal structures was an intellectual self-indulgence, an elitist retreat into professional concerns. Minimalism was sometimes formalist too, of course, but its processes were so perceptually obvious as to be self-effacing - so exaggeratedly foregrounded, one might say, that you forgot about them. Postminimalism certainly attracted some composers - Janice Giteck, Elodie Lauten, Daniel Lentz - whose music dealt with political issues and diverse cultural influences. But the emphasis of the music, and its most original features, were on aspects of musical material, process, and syntax.

The 1980s - decade of performance art and world music - were all about teasing out music’s political significance, under a deconstructionist-driven assumption that one could read a person’s politics, conscious and unconscious, in the structure of a work. Abstraction seemed exposed as the irrelevant mind-game of privileged white males. It has certainly been that, at times. But one of the pendulums that swings back and forth in the history of art is that between society’s claim on artistic meaning and art’s own need to define its inner principles. Perhaps postminimalism picked an inauspicious cultural moment to develop a new musical language of auditory illusions based on minimalism. But at some point people will once again become fascinated by music’s inner workings, and when this happens, I hope there will be some recognition of all the wonderful territory postminimalism has explored.

I'm not someone to whom "stories" tend to happen. But I told a story from my youth in class yesterday that I don't believe I've ever made public.

In 1982, the New Music America festival was in Chicago, directed by Peter Gena (my by-then-former composition teacher) and Alene Valkanas. I was "administrative assistant," third in command. Fresh out of grad school, I had reached the hoary age of 26. The festival was being funded by the city of Chicago, via Mayor Jane Byrne's office; the official title was "Mayor Byrne's New Music America." The day before the opening, Dennis Russell Davies was rehearsing Steve Reich's Tehillim with members of the Chicago Symphony in Orchestra Hall, for the festival opener which would be one of the work's first performances. The meter changes in that piece are a nightmare. At the end Reich started complaining that the piece wouldn't be ready, that he'd have to cancel the performance unless they could get another hour's rehearsal. Dennis Russell Davies called out from the stage and asked for authorization to keep the orchestra working for an extra hour. I was the only representative in the hall of either the festival or the city. It was explained to me that the orchestra cost $15,000 an hour.

I ran out to the pay phone in the lobby. I called Alene; she was nowhere to be found. Called Peter; he was nowhere to be found. I hung up the phone, pasted a smile on my face, sauntered back into the auditorium, and with a completely unjustified air of false confidence, gave the Maestro an OK sign and yelled, "Go right ahead!" They rehearsed for another hour, and the subsequent performance went swell.

My salary for that year was $12,000, so if they had decided to take the $15,000 out of my salary, there wouldn't have been room. But before the bills got presented to the city, Jane Byrne was voted out and Harold Washington was voted in. I imagine his staff had no idea what the NMA '82 cost overruns were all about; they just paid them and no one ever said anything.

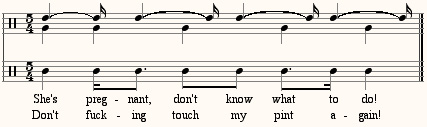

The rhythm in question, perhaps totalism’s second-favorite rhythm after 8-against-9, is an interference of two periodicities, one five units long against another 4 units long. It is given here with its standard American mnemonic device, and also with the one I learned in England:

Several of Mikel Rouse’s pieces for his totalist rock quartet Broken Consort from the mid-1980s revolved around this rhythm. One that did so entirely was High Frontier. In High Frontier Mikel applied a Schillinger technique to this rhythm that was interestingly close to one of Stravinsky’s 12-tone usages. Stravinsky would sometimes rotate through the 12-tone row, moving the first note to the end of the row and then the second note, and so on; likewise, Mikel would take two notes off the front of the rhythm and place them at the end, then do the same with the next two notes, and so on, resulting in the following rhythmic patterns:

Every rhythm in High Frontier, except for the steady 8th-note pattern in the keyboard and drums, is either one of these rhythms or a 2X or 4X augmentation of it. Through these he runs a permutation pattern of six pitches: low F, A-flat, B-flat, B, D-flat, and high F. As I once wrote about the work,

High Frontier sometimes sounds like it is in 5/4 meter, at other times like 4/4 with quintuplets; at other times the listener can perceptually move back and forth at will between these meters, as in an optical illusion. The various rhythms are predetermined numerically to support each other; a slower-rhythm bass line, for example, may coincide with a quicker saxophone melody on every fifth beat, outlining a subtle secondary accent. The surface of Rouse’s music is lively and varied, while the background exerts a consistent, unifying structural influence. The listener can rarely identify by ear what process is going on, but gets a strong sense of an unfolding, internal logic. [“Downtown Beats for the 1990s: Rhys Chatham, Mikel Rouse, Michael Gordon, Larry Polansky, Ben Neill,” in Contemporary Music Review, 1994]

You can listen to High Frontier here.

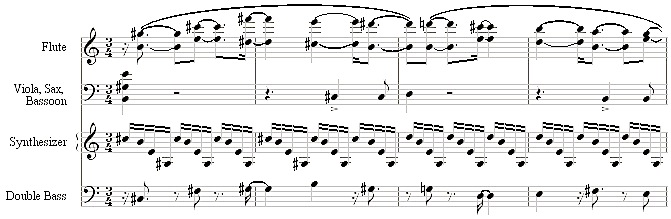

In my own music based on moving among various pulses, inspired by Hopi and Pueblo rhythms, I often used a quarter-note tied to a 16th as a basic pulse, along with quarter-notes, dotted 8ths, and so on. In “Venus” (1994) from my multi-movement work The Planets, I decided to divide the ensemble in half, one half playing a 5/16ths pulse against the others playing a quarter-note pulse - much like the middle movement of Ives’s Three Places in New England, only 5:4 instead of 4:3. “Venus,” couched in 3/4 meter with a running 16th-note arpeggio in the synthesizer, is filled with durations and phrase lengths of five 16th-notes, five 8th-notes, and/or five quarter-notes. These durations pile up subtly in the beginning, and then when the main theme begins, the eight-member ensemble begins to split in two, the synthesizer and lower winds marking the 3/4 meter as the flute, oboe, and bass play a beat only 4/5 as fast:

The theme, moreover, is in five-beat groupings, a kind of virtual 5/4 meter that imposes a 25/16 meter over the notated 3/4 meter. As the two tempos thicken and continue, it can be difficult, as in High Frontier, to tell whether you’re listening to 3/4 with a 5/16 beat superimposed over it, or 5/4 with quintuplets. At the end of the piece, however, the four and five trade roles, so that the woodwinds are now playing the quarter-notes, and the synth is grouping 16th-notes into fives:

You can hear “Venus,” from The Planets, here, played by the Relache ensemble.

Both of these pieces represent totalism's earlier, "heroic" phase, in which we were willing to go to great lengths of ensemble difficulty to achieve sonic illusions from polyrhythms. The next two works, though, relax into a milder polyrhythmic usage.

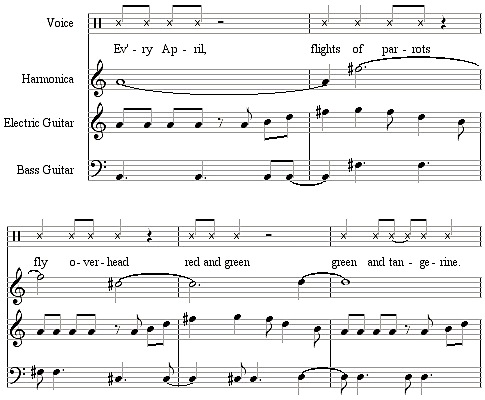

Rouse’s 1995 opera Failing Kansas, based on the murders of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, returned to the 4-against-5 rhythm on a less virtuosic level. A five-beat isorhythm, divided 3+3+1+3 in 8th-notes, is a recurring idea in the work:

![]()

The middle of the second scene, “The Last to See Them Alive,” is based on five- and ten-beat cycles over which a more “normal-sounding” 4/4 sometimes asserts itself. The effect is less illusionistic than in High Frontier, but you still have a continual choice as to which meter to tap your foot to (notice the 5/4 ostinato in the bass, reinforced by the harmonica):

You can listen to the two-and-a-half minute excerpt of Failing Kansas that illustrates this tempo effect here. Or, you can listen to the entire ten-minute scene, “The Last to See Them Alive,” here. If you listen to the whole scene, you’ll hear a different, equally elegant effect at the beginning. The opening lyrics are from a hymn favored by Perry Smith, one of the murderers:

I come to the garden alone

Where the dew is still on the roses

And the voice I hear

Falling on my ear

The Son of God discloses

This hymn is in 12/8 meter and spoken that way, though the instrumental music is in 4/4 (the 8th-note equal between the two), creating a subtle out-of-phase relationship of 3+3+3+3 against 3+3+2 patterns. It’s so simple one could easily miss it - in 1995 it took me several listenings to analyze why the rhythm of this passage is so charmingly off-kilter.

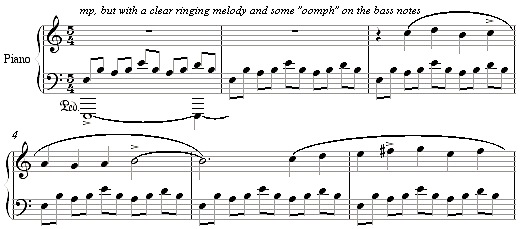

Several years later, in 2004, I came back to the 5:4 idea in the “Saintly” dance for the Private Dances I wrote for pianist Sarah Cahill. Since one player needed to play both rhythms, this was a simple matter of placing 4/4 phrases (marked with accents only for illustration) above a 5/4 ostinato:

You can listen to “Saintly” here. Once again, at the end, I couldn’t resist switching the rhythmic roles as I had in "Venus," changing to a 4/4 ostinato in the left hand with five-beat phrases in the right.

And, as a bonus track, here’s a four-minute percussion work by John Luther Adams, Always Coming Home, which will give you your fill of five-against-four tempos if you hadn't had it already. It's from a larger work called Coyote Builds North America, from 1990, the great heyday of 5:4.

Couple of soundbites I've run across on the web deserve wider play. One comes from Mary Jane Leach's capsule history of Downtown music posted to Sequenza 21. She mentions that the Bang on a Can festival "elbowed out what had been the real downtown scene." I've heard other Downtowners (or former Downtowners, if you insist on regarding the scene as dead) state this matter-of-factly too, that Bang on a Can came in, sponged up all the available funding and PR for Downtown music, rode off into Lincoln Center, Banglewood, and the sunset with it, and left an empty shell behind. Certainly they convinced those outside the scene that Downtown music is what they represented, even as they explicitly denied having any interest in Downtown.

Second is a quotation given in Elodie Lauten's blog of what the irrepressible Jon Szanto (of Harry Partch performance fame) said the problem with Postclassical music was: "It's too hip for the straights, and too straight for the hips." I had said something similar in many articles with titles like "Music of the Excluded Middle," but I lack Jon's talent for turning a phrase. He shoots straight from the hip.

I have two performances on the opposite side of the continent this week, while I'm stuck here in the snow. First is Friday, February 17, by the Group for New Music at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, directed by Michael Hicks. He's giving a "live" performance of my Disklavier piece Tango da Chiesa, on a program in honor of Morton Feldman's 80th birthday. The program:

Bunita Marcus: Untrammeled Thought

Jürg Baur: Petite Suite (for flute quartet)

Leo Brouwer: Cuban Landscape with Rain (for guitar quartet)

Kyle Gann: Tango da Chiesa

Michael Hicks: Lamentation, and

Feldman: Palais de Mari , played by Hicks

Then this Saturday, February 18, Sarah Cahill will play two of my Private Dances at the REDCAT Theater in Los Angeles, starting at 8:30. The program features 14 composers who are all recorded on the Cold Blue label. The lineup is as follows:

Read Miller: Come out, sit awhile; break the bottle, and you is lost

Kyle Gann: "Sad," "Saintly" from Private Dances

Michael Jon Fink: I Hear It in the Rain

Larry Polansky: Eskimo Lullaby

Steve Peters: Paris, once

Rick Cox: Later

John Luther Adams: The Light That Fills the World

Peter Garland: Hermetic Bird

Chas Smith: P770

Daniel Lentz: Lovely Bird and Requiem

David Mahler: La Cuidad de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles

Michael Byron: as she sleeps

Jim Fox: Colorless sky became fog

Barney Childs: Variation on Night River Music

About half the music is for piano, played by Sarah, but several are ensemble pieces, including the Robin Cox Ensemble playing John Luther Adams's The Light That Fills the World. Cold Blue is a lovely label, and it sounds like a great program, if I say it myself that shouldn't.

The first weekend in March, Sarah plays my Time Does Not Exist at Santa Fe New Music, but I'll fill you in on that later. Somebody show up and tell me how they went!

If anyone would like to present my music on this coast, please speak up.

I've put up a little display on my office door, Xeroxes of the opening pages from seven pieces of music:

J.S. Bach: Violin Sonata in G minor (autograph)

Josquin des Prez: Alma Redemptoris Mater

Erik Satie: Pièces Froids

Leo Ornstein: A Reverie

Wayne Shorter: Nefertiti

Christian Wolff: Snowdrop

Frederic Rzewski: Attica

What do they all have in common?

There's not a printed dynamic marking in the bunch. Not a p, not an f, not a hairpin.

Student composers in my environment are mandated to fill their scores with dynamic markings, crescendos and articulation markings on each phrase, with the implication that every phrase must have a nuanced, curvilinear dynamic envelope. By exhibiting successful works that all break that rule, I demonstrate that there is nothing that every piece of music has to do or have. Nefertiti, you will object, is jazz; exactly, the new music I'm interested in often exists in a state in between classical and jazz or pop, and does not micromanage the performer. Wolff's Snowdrop doesn't even specify clefs. Alma Redemptoris Mater was written before dynamic markings existed; much of the new music I love comes from a Renaissance influence. The Rzewski score has some dynamics lightly pencilled in by a performer, showing how each performance gets to reinterpret the piece anew.

Do I have anything against music of fluid, specified dynamics? Not at all. Just last semester I made one student fill a score with dynamics, because it was awash in energetic gestures that would have looked confusing without the dynamic volatility acknowledged. What I do have something against is conformity, especially the coerced kind.

I am in receipt of a book by Luca Conti entitled, Suoni di Una Terra Incognita: Il Microtonalismo in Nord America (1900-1940). It's published by Libreria Musicale Italiana. As you may have surmised, it's in Italian. There is much discussion of Ives, Cowell, Chavez, and Partch. I am mentioned, and several of my articles are listed in the bibliography. There are diagrams with lots of numbers and strangely configured keyboards. It looks interesting.

Jan Herman sent me this link, and I absolutely laughed my ass off. It would be churlish not to share such effective medicine with the world. (If the link doesn't still take you to Ten Worst Album Covers, try this: http://salamitsunami.com/archives/91.)

Now that I've got more than 7500 mp3s on each of two external hard drives, one for home and one for school, my attention has turned to PDF scores. I'm collecting a lot of Beethoven from the Sheet Music Archive, and I recently wrote an article about Melissa Hui entirely from PDFs she sent me. Now I've found out, through a post at Sequenza 21, that Leo Ornstein's son is inputting Ornstein's music and offering it to the public through Other Minds, so in a few minutes yesterday I went from years of wishing I had scores of Ornstein's early piano music to carrying around more than I could possibly need of it on my computer. And from a comment on the tuning groups, I chanced to learn that the manuscript scores of Tui St. George Tucker - a quarter-tone pioneer who, it turns out, died in 2004 without my being informed - are available at her web site. Of course, a dozen or so of my scores have long been available as PDFs, although if I've received a single performance from the fact, no one's ever apprised me. I love having hard copy, which is indispensible for certain purposes. But I also waste a tremendous amount of student time, and mine, looking for scores that I know are in my library somewhere, that somehow never manage to get placed back where I think they live. With my PDF scores, it's a problem I'll never have. (Though I've also run into the difficulty that my own PDF scores don't seem to print out correctly on certain computers. I'll be glad when all this gets standardized.)

Art Jarvinen weighs in on the relation between totalism and dance:

I just watched Blow Up again. Had not seen it in a long time. There is a slightly interesting moment around 50 minutes in, where the bored photographer guy and the scrawny uninteresting woman are smoking and listening to groovy music. She's trying to move to it, and she's really lame. He gets her to move slooowly, "against the beat." She starts to get it, and it's a totally Totalist moment....

I always wondered why I couldn't dance. I couldn't dance to The Twist, or "I Wanna Make It With You." But I could not NOT dance to Captain Beefheart. "Lick My Decals Off Baby" is my disco record. I have to move when I hear it, both knees going in different rhythms, one arm not knowing what the other one is doing - until it all comes around after…a while - or not.

We understand difference tones. You talk about ratios all the time. Totalist rhythmic structures usually add up to something - a big honkin' downbeat that is so satisfying, and that you feel coming for a long time before it hits.

Composer Paul Epstein told me the other day that the only thing wrong with my Disklavier disc was that he couldn't exercise to it - the different tempos kept throwing him off. I had had the same experience. When working out on a treadmill I often listen to Postclassic Radio. One day Michael Gordon's Trance was on. I almost fell off. I could not keep moving in tempo to the jerking around of all those dotted quarters and triplets fighting with each other. Wherever we totalists make our money, it's not going to be through the sale of totalist exercise videos.

Sites To See

AJ Ads

AJ Arts Blog Ads

Now you can reach the most discerning arts blog readers on the internet. Target individual blogs or topics in the ArtsJournal ad network.

Advertise Here

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Exploring Orchestras w/ Henry Fogel

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary

Tyler Green's modern & contemporary art blog