PostClassic: November 2005 Archives

by speeding up the first three 8th-notes notes and prolonging the last two (even extending the left-hand D-flat into a quarter-note), turning the meter into a more conventional 6/8, as you can hear here, and disappointingly taking the edge off of Janacek's rhythmic originality. (In fact, when the music reverts to 2/4 in the 5th measure, Schiff's 8th-note suddenly slows down by 50 percent, making it clear that he was feeling the 5/8 as 2/4 with triplets all along.)

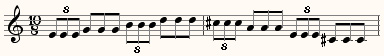

This wouldn't merit mentioning if it weren't so common. Classical musicians are taught early in life that a measure is a rhythmic unit, divided into two or three parts, and if divided into more, then divded according to a symmetrical heirarchy: 2 groups of 2, 2 groups of 3, 3 groups of 3, and so on - or not and so on, because that's about it. Of course, quite early in the 20th century - On an Overgrown Path is a hundred years old - composers opened up a new conception of meter, as a quantity of equal or even unequal units. Musicians accustomed to playing composers as long-dead as Stravinsky and Copland are used to negotiating 5/8 and 7/8 meter, but it's surprising how many professional musicians have never added the new paradigm to their repertoire. They recognize it and think they know how to do it, but when they start to play, their body-need for a regular beat, like Schiff's, overrules their visual cognition. I have to warn my students, some of whom gravitate to 13/16 and similar meters under the influence of notation-software-induced ease, that some classical players will have to be taught how to play the rhythm, and that they might not be teachable. Recently a student wrote a passage in 10/8 meter, with the following quite elegant rhythm that required four beats per measure, quarter-notes on 1 and 3 and dotted quarters on 2 and 4:

It seemed perfectly simple to him and me, but the performance, by professional players steeped in 19th-century music, was a disaster. They ended up speeding the non-triplet 8th-notes into triplets, and making it a kind of bumpy 4/4. No amount of pleading could get them to feel successive beats as unequal.

I face the same mentality when I show people my Desert Sonata for piano, which has a long moto perpetuo passage in 41/16 meter. Certain people look at it and exclaim, incredulously, "How do you COUNT that?!" Well, of course, you don't count it, but if you will play the 16th-notes evenly and in the order indicated, I promise it will come out all right. What they want, of course, is some heirarchical division of 41 that they can funnel all those 16th-notes into, and there just isn't one. (Please don't be tiresome and advise me to renotate it in 4/4 - the 41/16 clarifies the underlying isorhythm, and mangling it into 4/4 would turn it into an unmemorizable mishmash.) By now this new metric paradigm is very common among young composers - Sibelius notation software will handle meters up to 99/32 just as easily as 4/4 - and so it's astonishing to still find it so missing in classical music pedagogy. In 1947 Nancarrow turned to the player piano because the musicians he met couldn't play the comparatively simple cross-rhythms he was writing. Were he to come back today, there are circles in which he would find that things haven't improved much.

In his [1938] essay, "Paleface and Redskin," the literary critic Philip Rahv claims that American writers have always tended to choose sides in a contest between two camps the result of "a dichotomy," as he put it, "between experience and consciousness...between energy and sensibility, between conduct and theories of conduct." Our best-selling novelists and our leaders of popular literary movements, from Walt Whitman to Hemingway to Jack Kerouac, number among the group Rahv called the redskins. They represent the restless frontier mentality, with its reverence for the sensual and intuitive over the intellect, its self-reliant individualism and enthusiasm for quick triumph over obstacles....Of course, it would be entirely illegitimate to make any such distinction in the history of American music. No no no no no no no. Music is just music, and we shouldn't try to draw distinctions within it. American music is just anything American composers do. Because I said so, now shut up and practice your scales.While the redskins took to the open road, jotting down their adventures along the way, the palefaces tended to congregate in the cities, where they drew heavily on European literary and intellectual traditions. They put at least as much stock in the value of artistic transformation and intellectual reflection as they did in capturing the raw data of the emotions and senses for their portrayals of human experience. James and Eliot would be leading figures among the palefaces. Both of them eventually left America, a society that they came to regard as crude, to spend the balance of their lives in England.

Gestalt Therapy by Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman

(In other words, the above is basically what Peter Garland and I and a few others have been saying about American composers forever, to an answering, contradictory chorus of anti-intellectuals who don't believe any distinctions should ever be drawn.)

their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, "Saintly" from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow's Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I'll see you there, but I'll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.

their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, "Saintly" from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow's Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I'll see you there, but I'll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.

So I was knocked for a loop by a new Bis CD by pianist Lera Auerbach called Tolstoy’s Waltz. My impression that the title was mere metaphor gave way as I finally deigned to give the thing a closer look, and yes, the author of War and Peace did actually write a waltz, and Ms. Auerbach has recorded it. Not only that, there are two preludes and a sonata here by Boris Pasternak of Doctor Zhivago fame, a song by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, a waltz by the great choregrapher George Balanchine, plus pieces by other Russians like the painters Pavel Fedotov and Vasily Polenov, the intellectual Vladimir Odoyevsky, and the playwright Alexander Griboyedov. Eight famous Russians, not a professional composer in the bunch, though liner notes by Marina Tiourcheva detail their musical training and accomplishments to an extent that should embarrass us 20th-century-trained Americans for being uncultured fools by comparison. Apparently any educated 19th-century Russian of artistic bent played Beethoven’s sonatas passably well and tried his hand at composition just to see, you know, if he had a knack for it.

Most of them do not, noticeably. The creator of Anna Karenina turned out a nice little waltz with oom-pah-pah in the left hand and some pleasingly sharp appoggiaturas in the right - no more can I say for it. Pasternak, however, was on another level. His mother was a pianist and the family knew Scriabin, which accounts for a strong Scriabin influence on young Pasternak’s preludes, but isn’t sufficient to explain the delicate and arresting textures of his 13-minute, one-movement sonata of 1909. That’s a major work. Polenov had a dark imagination, if no technique beyond the ordinary; but I would have to become enamored of his painting for the music to have any interest. Diaghliev’s song is uninspiredly Wagnerian, with too many tremolos in the piano. Balanchine’s waltz is far more imaginative than Tolstoy’s, with a listless grace that knows how to play off the meter rather than tread on it - one could easily imagine choregraphing the piece, and I think I’ll take a copy to the dance faculty here. But I’m glad to think Tolstoy wrote a waltz, even if I file this disc under Pasternak. And I’m glad that people like Lera Auerbach are taking care of the musical estates of great writers and painters and thinkers, no matter how slim their content.

UPDATE: Joseph L. in the comments reminds me that I forgot about one of the most interesting non-composer composers, Ezra Pound. He considered setting words to music one of the major forms of poetic criticism, and I've long been a fan of his Testament of Villon - but Other Minds owes me a copy of their new Pound CD, and I guess I'll have to bug them for it. Pound was a big early influence on my development, and I even studied Provençal in college with a Pound fanatic. To this day I can quote Arnaut Daniel from memory:

Iu suis Arnaut, q'amas l'aura

E chatz la lebre ab lo bou,

E nadi contra suberna.I am Arnaut, who gathers the wind,

And hunts the hare with the ox,

And swims against the incoming tide.

I've always thought I should have moved to Europe decades ago, and never more than in the last five years. But a composer friend who lived in Europe for many years told me this week why he moved back to the U.S. It seems that when he applied for grants there, to foundations which preserved the anonymity of their applicants [emphasis added later], his music was regularly rejected with the comment: "too American-sounding."

UPDATE: I have to apologize for so badly misstating this slender anecdote that no one has yet gotten the point of it. The point is not that Europeans don't like American music. In my experience, American music, especially the experimental variety, is far better appreciated in Europe than it is here - that's the upside of expatriation, which I erroneously assumed everyone would understand. The point is that, if you're living outside your own country, and you submit work anonymously, no one can tell you're an expatriate, and there is a danger that your music will be judged in ignorance of its true context. That's all. This composer's music was rejected not because it sounded American, but because it was assumed he was a Dutch composer imitating the Americans. Had they known he was an actual American, they would likely have thought it was just fine and natural that his music sounded American. He had, in fact, been invited to live in Holland because the Dutch liked his music. The irony is that he was famous enough to get a job in Europe, but got discriminated against when they didn't know he was American. The still-possibly-unfortunate prejudice to which the item alludes is not a prejudice against American music, but against European nationals so impressed with America that they imitate its music, and for whom an actual anonymous American might be mistaken. My apologies to the continent of Europe, and all others closely devoted to Europe, for any misunderstanding. The point of the anecdote, if it still has one, would have remained unchanged if Antarctica had been named instead of Europe.

It's exactly analogous to the comment that Laurie Anderson once overheard. As she was walking through Manhattan one day, someone looked at her and said, "Great, another Laurie Anderson clone."

Quand j'etais jeune on me disait: Vous verrez quand vous aurez cinquante ans.Satie's Dream (1975)J'ai cinquante ans. Je n'ai rien vu.

Erik Satie

The assault on liberal education from the left presumes that pedagogy must be "student-centered," with professors no longer "teaching" but "facilitating" or serving as "architects of interaction" who "enable" students to teach one another. The assumptions underlying this methodology are democratic and, as such, inimical to a type of education that prizes the difficult or esoteric. For example, the "communicative approach" is the most popular one in foreign-language classes across the country. Beginning students interact with one another more than with the instructor. Instructors are further discouraged from correcting mistakes for fear of inhibiting self-expression. This model emphasizes oral communication (and students do speak with greater ease), but at the cost of precision, knowledge of grammar, and ability to read serious texts.... One could draw similar parallels to other courses, including English composition, where many instructors do not teach or correct grammar. As the National Council of Teachers of English would have it, students have the "right" to their own language. Paradoxically, this approach is more insidiously hierarchical than the old teacher-centered one: Teachers consciously withhold their knowledge and high-culture experiences, thereby limiting the students' educational opportunities.

Give me a break. This is the kind of crap that conservatives make up and attribute to liberals so that Rush Limbaugh can come along and discredit us for allegedly believing it. I consider myself pretty far left, and certainly people are under the impression that the college I teach in is one of the most liberal liberal arts schools in the country. And there is no way in hell my college administration would put up for a minute with this anti-intellectual claptrap, nor would anyone on the faculty ever ask them to.

I thought I'd never live to see the day that more than three hours of Julius Eastman's music would be commercially available. But today is that day, for New World's three-disc set of archival recordings (New World 80638-2) - titled Unjust Malaise, an anagram of Eastman's name - is now in my hands. In case you haven't been tuned in to the recent buzz, Eastman (1940-1990) was a gay African-American whose rivetingly powerful postminimalist music confronted issues of race and sexual identity, and who died under rather mysterious circumstances at the age of 49. (He died at Millard Fillmore Hospital in Buffalo, but the cause of death remains maddeningly vague. Some assume he had AIDS - the family says not so.)

I thought I'd never live to see the day that more than three hours of Julius Eastman's music would be commercially available. But today is that day, for New World's three-disc set of archival recordings (New World 80638-2) - titled Unjust Malaise, an anagram of Eastman's name - is now in my hands. In case you haven't been tuned in to the recent buzz, Eastman (1940-1990) was a gay African-American whose rivetingly powerful postminimalist music confronted issues of race and sexual identity, and who died under rather mysterious circumstances at the age of 49. (He died at Millard Fillmore Hospital in Buffalo, but the cause of death remains maddeningly vague. Some assume he had AIDS - the family says not so.)

The New World set contains, in its entirety, a January, 1980, concert at Northwestern University at which I was present as a grad student, including three pieces for multiple pianos - Gay Guerrilla, Evil Nigger, and Crazy Nigger - along with Eastman's own remarkable spoken introduction. Also here are his early signature piece Stay On It, which the Buffalo Creative Associates toured all over Europe in the '70s, plus If You're So Smart, Why Aren't You Rich? and The Holy Presence of Joan d'Arc. Rich, powerful stuff, based on Eastman's "organic" conception of music whereby new information is gradually added to a repeating sequence as old information is gradually taken away. And the copious liner notes are by moi - I was surprised, thinking back, to realize how many encounters I had with Eastman between 1974 and '89. He was a friend of my grad-school composition teacher Peter Gena, but I knew him even before I knew Peter, from appearances at Oberlin (with Petr Kotik) and, notoriously, at June in Buffalo 1975. Naturally, Eastman will be Postclassic Radio's Composer-of-the-Month for Nov. 16 to Dec. 15 (hey, at Postclassic Radio we think outside the box) as soon as I can load up Crazy Nigger here, and I've got some other archival performances to play not on the New World set.

Photo of Eastman in Perugia, 1974, by Peter Gena.

13/12, 13/11, 13/10, 13/9, 13/8, 13/7 (13/6, 13/5, and so on, are merely octaves of those already mentioned)

12/11, 12/7 (12/10 is the same as 6/5, 12/9 = 4/3, and so on)

11/10, 11/9, 11/8, 11/7, 11/6

10/9, 10/7 (10/8 = 5/4, 10/6 = 5/3)

9/8, 9/7, 9/5

8/7, 8/5

7/6, 7/5, 7/4

6/5

5/4, 5/3

4/3

3/2

1/1

It’s 29 pitches in all, all with fairly simple relationships to the tonic, because of which the whole piece takes place over a rhythmicized tonic drone. I figured out that I could make different scales within this network by taking all notes expressible by the form 13/X, or 11/X, or X/7, and the scales with the smallest numbers would be closest to simple tonality, while the larger-numbered scales will have a much more oblique relationship. Thus, by wandering through the 29 pitches on these different scales, the piece goes “in and out of focus,” sometimes comically random-sounding, sometimes purely and simply in tune, with every gradation in-between - and all with a tremendous economy of means. I’ve put it up for you to hear it here. The duration is just under five minutes, the title: Triskaidekaphonia. More detailed information about the tuning and compositional strategy is here. Only a trifle, perhaps, but it provides yet another bit of proof of the miraculous nature of the whole number series.

1. The best paper I heard at the toy piano conference at Clark University last week was by the irrepressibly enthusiastic Helen Thorington, of NPR and radio sound art fame. She came to tell about her Networked Performance blog, a site where she and other bloggers keep track of internet performance projects from all around the world. The stuff she showed us ranged from unbelievable to hilarious, and mostly involved technologically brilliant attempts to get lay audiences more involved in art. The best approach to the site, I think, is to go down to the menu on the lower right hand side and look through the categories of different types of art. I was most tickled by the “Wearables,” new high-tech clothing, like:

Wearable Keyboards by a Professor Tsukamoto of Kobe University, piano key patterns sewn into the fronts of dresses, or the arms of shirts, that create sound when touched (giving new meaning to my oft-repeated expression that [French accent, please] “a beyootiful woman must be played like an eenstrument”);

Aware Cuffs, knitted cuffs for your wrists with lights that will light up when you’re within range of wireless internet service;

Random Search underwear, developed by Ayah Bdeir, that responds to metal detector searches in airports with rippling LED lights.

But there’s tons of more stuff - sites that you can draw on and have the drawings turn into sound, mirrors that can recognize your identity and give a personalized digital response, communal iPods, and tons more. A few hours’ immersion will make the timid old 20th century seem to fade away from consciousness, and will bring to life the famous statement by science fiction writer William Gibson: “The future is already here, it’s just unevenly distributed.”

2. Composer/video artist/whatever-he-wants-to-be-called-these-days Henry Gwiazda has just inaugurated a web site to accompany (and sell) his imminent Innova DVD titled, "She's Walking...." But this is more than an informational web site: it’ll let you listen to excerpts of Gwiazda’s music and watch clips from the DVD, but will also ask you personal questions and offer bits of wisdom like, “Perhaps each day is about the same because we need the time to practice what to see and what to hear.” And you can upload a photo of yourself (or anything else) and have it diffracted via Gwiazda’s abstracting imagery. Gwiazda’s music is made up of samples of real-life sounds combined with a humorous sense of poetry; his videos focus over and over on details from daily life in an attempt to make us see the world around us differently. Beautiful, touching stuff. And there’s also a link to the program notes I wrote for the DVD, though not to my filmed interview with Gwiazda that comes with it.

Enjoy!

Sites To See

AJ Blogs

AJBlogCentral | rssculture

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Andrew Taylor on the business of arts & culture

rock culture approximately

Laura Collins-Hughes on arts, culture and coverage

Richard Kessler on arts education

Douglas McLennan's blog

Dalouge Smith advocates for the Arts

Art from the American Outback

Chloe Veltman on how culture will save the world

For immediate release: the arts are marketable

No genre is the new genre

David Jays on theatre and dance

Paul Levy measures the Angles

Judith H. Dobrzynski on Culture

John Rockwell on the arts

innovations and impediments in not-for-profit arts

Jan Herman - arts, media & culture with 'tude

dance

Apollinaire Scherr talks about dance

Tobi Tobias on dance et al...

jazz

Howard Mandel's freelance Urban Improvisation

Focus on New Orleans. Jazz and Other Sounds

Doug Ramsey on Jazz and other matters...

media

Jeff Weinstein's Cultural Mixology

Martha Bayles on Film...

classical music

Fresh ideas on building arts communities

Greg Sandow performs a book-in-progress

Harvey Sachs on music, and various digressions

Bruce Brubaker on all things Piano

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Greg Sandow on the future of Classical Music

Norman Lebrecht on Shifting Sound Worlds

Joe Horowitz on music

publishing

Jerome Weeks on Books

Scott McLemee on books, ideas & trash-culture ephemera

theatre

Wendy Rosenfield: covering drama, onstage and off

visual

Public Art, Public Space

Regina Hackett takes her Art To Go

John Perreault's art diary

Lee Rosenbaum's Cultural Commentary