“I knew at fifteen pretty much what I wanted to do… I resolved that at thirty I would know more about poetry than any man living, that I would know the dynamic content from the shell…”

– Ezra Pound, “How I Began” (1913)

A thrill ran up my spine when I read those words in college, for I harbored an identical ambition with respect to music. I recognized a kindred spirit, someone who was not only obsessed with an art form, but for whom creating in that art form was not enough: he had to devour and digest the entire history of the art, the repertoire going back to the dawn of recorded history. The obsession was not with “my art,” but with “all art leading up to mine.” (Pound was not yet thirty when he wrote that.) I became an Ezra Pound fanatic for several years, and the Pound preoccupation intersected with a burgeoning love for medieval music to promote my self-immersion in the troubadours (or, as I prefer to spell them in Provençal rather than French, trobadors). I actually studied Provençal for a semester with a Pound scholar, named Peter Way, who was living in Oberlin, Ohio, at the time but not teaching there. I memorized passages of Pound’s early poems, especially the Provençal-inspired ones; the Cantos I found forbidding. Perhaps the disturbing reputation of Pound’s later decades played some role in Pound’s finally dropping outside my focus. Still, when our medieval literature professor at Bard teaches the troubadours, she brings me in to lecture on the music, and I have a blast doing it.

A thrill ran up my spine when I read those words in college, for I harbored an identical ambition with respect to music. I recognized a kindred spirit, someone who was not only obsessed with an art form, but for whom creating in that art form was not enough: he had to devour and digest the entire history of the art, the repertoire going back to the dawn of recorded history. The obsession was not with “my art,” but with “all art leading up to mine.” (Pound was not yet thirty when he wrote that.) I became an Ezra Pound fanatic for several years, and the Pound preoccupation intersected with a burgeoning love for medieval music to promote my self-immersion in the troubadours (or, as I prefer to spell them in Provençal rather than French, trobadors). I actually studied Provençal for a semester with a Pound scholar, named Peter Way, who was living in Oberlin, Ohio, at the time but not teaching there. I memorized passages of Pound’s early poems, especially the Provençal-inspired ones; the Cantos I found forbidding. Perhaps the disturbing reputation of Pound’s later decades played some role in Pound’s finally dropping outside my focus. Still, when our medieval literature professor at Bard teaches the troubadours, she brings me in to lecture on the music, and I have a blast doing it.

In February I went to Kansas City to lecture on Ives, partially at the invitation of my friend David McIntire. Michelle McIntire, his wife and a singer and voice teacher, expressed a desire to perform some of my music, suggesting I write something for her. Michelle has a wide range but a low tessitura, with an especially nice quality in the octave around middle C. All of my songs for female voice are written in soprano register. I came home, pulled out the usual suspects among my poetry books. Low female voice I associate with sensuality, the sotto voce side of life. The troubadours registered in the back of my mind Рin my youth early-music groups sang them in the style of sacred music, but I always thought their celebrations of illicit sex would have been more at home in smoke-filled jazz clubs. I pulled out my old friend Pound and conceived of his troubadour poem Na Audiart sung with a cool, jazzy accompaniment of flute, vibraphone, electric piano, electric bass. Poem quickly led to poem, and a huge song cycle with the title Proen̤a (the Proven̤al word for Provence) exploded in my head.

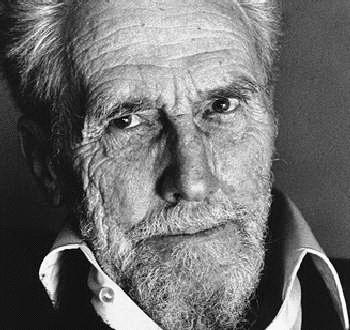

So now Proença comprises six songs lasting a projected forty-five minutes (of which I have a half-hour completed), and I’m not sure that will be the end of it. I have two Pound songs based on the warrior-troubadour Bertrans de Born (pictured), Na Audiart and Near Perigord* (excerpted); two Pound translations of troubadour poems, Arnaut Daniels’s “L’aura amara” and the anonymous alba “En un vergier sotz fuella d’albespi” (which Pound called the best alba ever written**); and two settings of 12th-century poems in Provençal, Bernart de Ventadorn’s “Pois preyatz me senhor” (with the original melody), and the Comtessa de Dia’s “Estat ai en greu cossirier,” which I picked in order to have a poem by a woman for which no pre-existing tune had survived. I could so easily go further, there are so many troubadour poems I love and Pound poems, and my poet friend Michael Ives introduced me to the tautly energetic troubadour translations of Black Mountain poet Paul Blackburn (1926-71), which I’d also consider. On the other hand it’s a lot of music to pour into Michelle’s brain, and an odd instrumentation to ask an audience to listen to for half an evening. As it is, she’s thinking about a winter premiere and recording it next summer.

So now Proença comprises six songs lasting a projected forty-five minutes (of which I have a half-hour completed), and I’m not sure that will be the end of it. I have two Pound songs based on the warrior-troubadour Bertrans de Born (pictured), Na Audiart and Near Perigord* (excerpted); two Pound translations of troubadour poems, Arnaut Daniels’s “L’aura amara” and the anonymous alba “En un vergier sotz fuella d’albespi” (which Pound called the best alba ever written**); and two settings of 12th-century poems in Provençal, Bernart de Ventadorn’s “Pois preyatz me senhor” (with the original melody), and the Comtessa de Dia’s “Estat ai en greu cossirier,” which I picked in order to have a poem by a woman for which no pre-existing tune had survived. I could so easily go further, there are so many troubadour poems I love and Pound poems, and my poet friend Michael Ives introduced me to the tautly energetic troubadour translations of Black Mountain poet Paul Blackburn (1926-71), which I’d also consider. On the other hand it’s a lot of music to pour into Michelle’s brain, and an odd instrumentation to ask an audience to listen to for half an evening. As it is, she’s thinking about a winter premiere and recording it next summer.

So I’m not sure how much further to go. I mentioned to a distinguished poet on the faculty that I was writing a song cycle on Pound and she spit out, “That bastard!” I know, but I do not believe in holding the artist’s faults against the art. Who knows but that I may be in the doghouse myself someday? And should my music therefore suffer? Pound’s later fascist sympathies aside (and I’m using only pre-1920 texts), those poems have been lovingly settled into the back of my brain for so many decades. Pound planted the seeds of a troubadour fascination forty years ago, and they only needed a drop of attention to blossom into a tropical forest of inspiration.

*It’s difficult to refer to Near Perigord when you’re very used to talking about the Danish composer Per Norgard.

**An alba is a formulaic medieval poem warning two lovers who shouldn’t be found sleeping together that the dawn is visible – presaging Romeo and Juliet and Tristan und Isolde.